Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Babe the Barbarian (Ruth, That Is)

My newest students beg for sports writing, and cannot abide either dragons or spaceships. They’re good kids, 8th graders who used to read voluminously for pleasure until junior high. Their parents are desperate to get them reading again. The boys are desperate to read freely again. So now I get to be desperate to learn about sports writing.

My newest students beg for sports writing, and cannot abide either dragons or spaceships. They’re good kids, 8th graders who used to read voluminously for pleasure until junior high. Their parents are desperate to get them reading again. The boys are desperate to read freely again. So now I get to be desperate to learn about sports writing.

Meet the students where they are. They can’t very well meet you where they’re not.

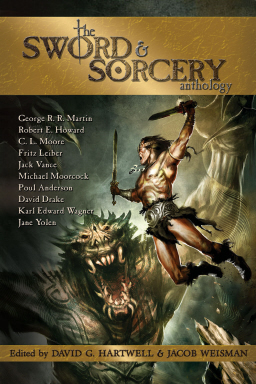

Fortunately, I had just started reading, on my own time, The Sword and Sorcery Anthology, edited by David Hartwell and Jacob Weisman. At first, as I pulled likely prospects from the sports shelves at Barnes & Noble, I grumbled quietly to myself about how I was going to have to set The Sword and Sorcery Anthology aside, perhaps for weeks, and for what? For Babe Bleeping Ruth and Joe Bleeping DiMaggio. I settled in at the cafe to cull the candidate books in my pile and tried to find a bright side. Some of the masters of the golden age of pulp also wrote boxing stories, or stories that happened to be about boxers. For people who see athletes as heroes, sports writing might hit the same sweet spot as heroic fiction. If I had to sink my time into this stuff, I would find some way to make it serve my writing.

Something David Drake said in his introduction to The Sword and Sorcery Anthology helped me cull that pile of books, and has been with me as I’ve started picking my way through the essays.

Drake relates this anecdote from one of the greats in fantastic literature:

Manly Wade Wellman, one of the finest pure storytellers I’ve ever known, was born in 1903 in Kamundongo, Angola; Manly’s father ran the clinic there for a medical charity….

Manly’s most vivid childhood memory was of the day a ten-year-old herdboy faced the leopard that was stalking his goats and killed it with his spear. That night, there was a banquet in the boy’s honor. He was seated on the high stool with the leopard’s skin, fresh and reeking, draped over his shoulders.

From his place of honor, the boy doled out a piece of the cat’s flesh to every adult male. When they had eaten the meat that would strengthen their spirits as well as their bodies, the men each in turn chanted a song of praise to the enthroned hero, recounting and embellishing his accomplishment. He has vanquished the monster which threatened our lives and our livelihoods!

Behold the hero! Hear his mighty deeds!

This is storytelling as the Cro-Magnons practiced it, and this is the essence of sword and sorcery fiction.

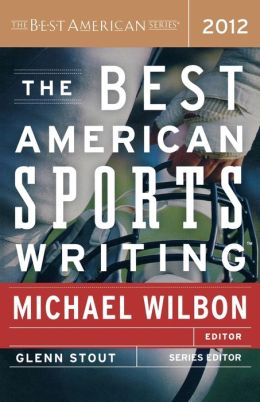

Certainly, most of the sports writing I’ve read so far has been in the mode of Behold the hero! Hear his mighty deeds! There are other pieces, later and longer ones mostly, that are more in the tragic mode of Behold the hero! See how the mighty have fallen! It’s only a short jump to imagine some of them as tales of sword and sorcery. Consider these titles from the 2012 volume of The Best American Sports Writing:

- The Ferocious Life and Tragic Death of a Superbowl Star

- Something Went Very Wrong at Toomer’s Corner

- The Two-Fisted, One-Eyed Misadventures of Sportswriting’s Last Badass

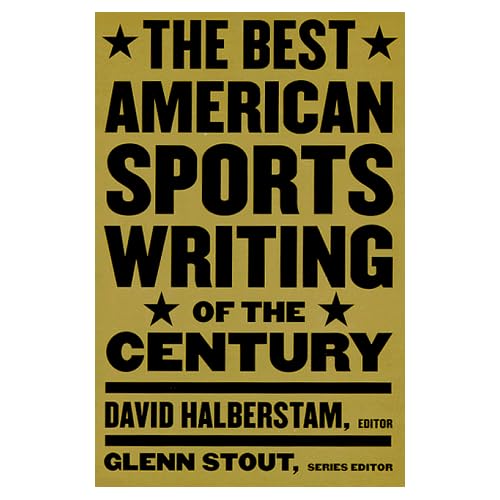

To me, the title of “Resurrecting the Champ,” an essay by J. R. Moehringer collected in The Best American Sports Writing of the Century, evokes Mary Shelley more than it does Robert E. Howard. Turns out it reads more like Raymond Chandler:

I’m sitting in a hotel room in Columbus, Ohio, waiting for a call from a man who doesn’t trust me, hoping he’ll have answers about a man I don’t trust, which may clear the name of a man no one gives a damn about.

Okay, for an opening sentence like that, I’ll read about almost anything. Even sports.

It turns out David Drake’s opening anecdote, in addition to offering me a way into sports writing, also nails down for me why it is that sports writing and its subject have never done much for me. “He has vanquished the monster which threatened our lives and our livelihoods!” chant the men in the story. And what monster does the athlete vanquish in most sporting events?

No monster, just a fellow athlete. What threat does the fellow athlete pose, to anybody other than the athlete we’re reading about? In most cases, none at all. In a boxing match, two potentially decent guys beat the snot out of each other, with nothing at stake that truly matters. In a football game, dozens of young men bludgeon their brains against the insides of their skulls, and for what? For bragging rights and cash? How much patience would I have for a fictional character who did as much harm for something as trivial? The more a sport resembles sword and sorcery combat in its results, the less interested I am in it. Conflict will only get you so far when the motives are shallow. Am I a prig? Maybe I’m being a prig.

As my anthropologist friends say when they talk about ethnographic interviews, You can’t learn anything new from a person while you’re judging him. My sports-obsessed students will bring me new things worth learning, if I let them. Meanwhile, I try not to have too many assumptions about what those things will be.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

I’m a huge hockey fan, and I’ve never been entirely sure why. Some of it has to do with the beauty of the sport, sure, but there are a lot of beautiful things in the world and I’m not a fan of all of them. Some of it has to do with the way in which my city’s team embodies the city, with the way the team’s had real historical and political significance. But that only kicks the can down the road. Why does the team matter so much? It’s frequently been said that in the 1950s the Montréal Canadiens meant something special particularly to Francophone fans — that the team became a symbol, that their winning became a way for a largely disadvantaged people to see themselves as winners. But in doing so they also became larger-than-life even to non-Francophones like me.

I suspect ultimately that a lot of sports is about symbolism. If you look at boxing as two guys beating each other up for money, it’s trivial. If you look at Moby Dick as a story about a guy trying to kill a fish (well, large seagoing mammal) then it’s trivial too. I think sports come to matter to people who aren’t playing the game because one invests meaning in the sport beyond the literal importance of a contest. So a good sports story, like any good story, catches some kind of symbolic essence through the depiction of specific events.

That said, I personally haven’t had the experience of reading a lot of great sports writing (I know it’s out there, I just haven’t read much). Dave Bidini’s Original Six anthology had some good hockey writing. And I loved, loved, *loved* Paul Quarrington’s Logan in Overtime. That might be bit raw for eighth-graders, though I remember my high school had me read (and watch) A Clockwork Orange when I was about 14, so who knows. But if you’re looking for non-fiction, there’s also this piece …

http://blogs.thescore.com/nhl/2012/04/25/something-magic/

… which I thought was wonderful, and which also seems to me have something to say about magic and fantasy and heroes. And is really directly relevant here, as it explains much more elegantly than I just did the level of significance a sport and a trophy can have.

Paper Lion. Friday Night Lights. Great sports writing DOES exist.

There’s not much difference between sports writing and heroic fantasy. Both require conflict, character, a sense of grim determination, and a narrative.

In fact, one of the things that I hate about ESPN is that they turn every sports event into the Iliad. This player or that off sulking because of a disagreement with a coach or another player.

A good sports writer finds the epic stories in games, a bad one just makes up drama.

I would recommend some good sports writing, but I’m guessing your students are going to want to read about particular players, much as I spent my middle school years only wanting to read about Superman. I must say, I don’t envy you your task–the heyday of American sports writing was about the same time as the heyday of pulp adventure magazines.

Matthew, thank you for the link to that wonderful article. That’s just the thing.

I lived a bunch of years just outside DC, land of the Redskins. The Redskins have a fight song, and despite myself, I know all the words. Ask anybody who has lived in or around that town, and odds are they’ll burst into song, if only ironically. There is a weird, or perhaps wyrd, relationship between a team and its city.

Mark, I’m finding out every day that you’re right. There’s some great stuff in those collections. Reading it feels a bit like reading Patrick O’Brian’s Aubry/Maturin novels–sometimes I have to cling to the plot through paragraphs at a stretch looking for any phrase I can parse, but I can still perceive the brilliance through the haze of unfamiliar terms.

Daran, you’ve called it in one. These boys want to read about basketball, and only basketball. Michael Jordan is the only guy they’re interested in whose name I recognized.

From my occasional bout of Olympics viewing, I know just what you mean about finding the epic vs. making up drama. You’ve put very clearly something that’s probably going to come up in conversation with the students again and again. So far, the most brilliant examples of finding the epic have been from the 1934 Olympics in Germany. No need to manufacture drama there.

[…] week I wrote about trying to understand sports writing as if it were a subgenre of sword and sorcery. For my students’ sakes, I’ll read just about anything–and usually when my […]