Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: No One Suspects the Spanish Inquisition (Wasn’t That Bad)

G. Willow-Wilson author photo by Amber French for SyFy.com

Since this column began this year, we’ve looked at the visual continuity of Jackson’s The Lord of the Rings (and why, ironically, it does a better job of wordlessly telling the sweep of Middle Earth’s history than Tolkien’s millennia-long, cultural stasis does), authenticity (and lack thereof) in The Witcher, and talked about the commonalities and differences of historical fiction and fantasy with several, excellent authors who work in both arenas. Along the way, I’ve coined a few loose terms (or rather, put existing ones into a hierarchy):

- Historical Fiction — Stories set in our world, but in generations prior to ours, generally just on the edge, or earlier, of living memory.

- Historical Fantasy — Stories set in the same milieu as the above, but with fantastical elements, sometimes very subtle (a lot of magical realism falls in here), sometimes not so — urban fantasy set in bygone eras, alternate history with vampires, or magic works, or orcs, etc. The world is clearly our own, so the fantastical elements can’t too dramatically upset that balance.

- Low Fantasy — Stories set in a secondary world, that is “realistic” to varying degrees but generally follows the real world in terms of technology, laws of physics, etc. A great deal of old-school Sword & Sorcery, and modern Grimdark fit in here.

- High Fantasy — sky is the limit. The secondary world has its own peoples, its own laws, and it is whatever the author wishes it to be. Anything from Tolkien’s Middle Earth to Zelazny’s Amber, the worlds of Brandon Sanderson, Robin Hobb and Robert Jordan all fit here.

In the future, we’ll look at these “big themes” and interviews with authors once more. But it’s time to look at how actual works play with these ideas, to varying degrees of success. And here is the trick: success as a novel, does not necessarily mean success as history. In these next two columns, I’m going to look at two authors whose work I really enjoy — and talk about why a particular work of theirs just didn’t work for me. In one case, because of a failure of historical authenticity; in the other, because of too much slavish devotion to it.

First up, The Bird King, by G. Willow-Wilson.

[Click the images for history-sized versions.]

A Disclaimer

This is a challenging article to write, as it becomes an analysis of a novel as both a work of fiction and as a cultural presentation, and in the latter, I find myself arguing for a little wokeness… for the freaking Spanish Inquisition.

But bear with me, because I don’t come to celebrate the Inquisition, but to hopefully bury them (and a lot of made-up legendarium surrounding them). In the process, I hope to argue for why it is sometimes better to put a tale in a secondary world — such as when the history of the real world just doesn’t play nice with good fiction.

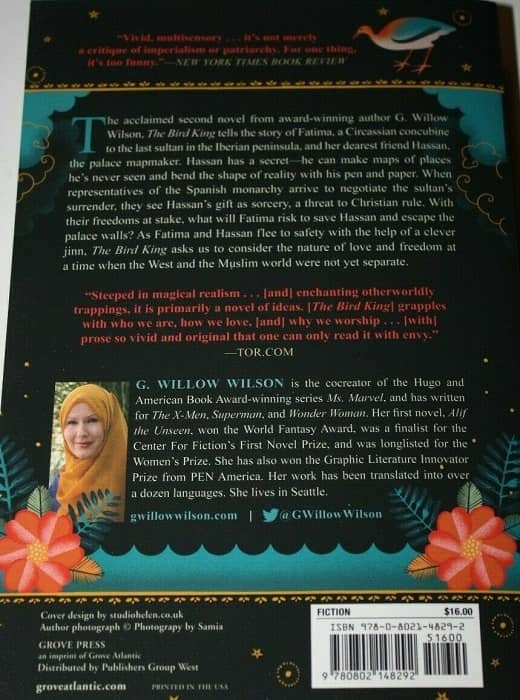

Firstly, there is simply the novel’s value as a fantasy – as something that sits somewhere between a modern fantasy and a medieval fairy tale. If you are familiar with Neil Gaiman’s approach to that sort of work: dreamy, metaphorical, sometimes more experiential than expository, and enjoy it (I do), then you will enjoy this story. On this level, the novel succeeds beautifully and shows why G. Willow Wilson is a major award winner, and the notable reimaginer of Ms. Marvel and a popular writer of Wonder Woman.

However, this is also an historical novel set, ostensibly, in Granada, 1491 at the moment of the Reconquista’s conclusion. This isn’t a story of Muslims vs. Christians, but of *people*: of friendship, love, loneliness and seeking to have something of one’s own. Unfortunately, the plot is built on one of history’s great lies.

|

|

The Bird King by G. Willow Wilson. Grove Press, February 2020 (paperback edition). Cover by Helen Crawford-White

The Premise

As Granada’s last sultan is negotiating the surrender of his city, one of the members of the Spanish retinue – a noblewoman turned lay-members of the Order of St. Dominic, and a licensed inquisitor – learns that there is a man at the Granadan court who can draw maps of places he has never been, and not always are they always accurate, but by adding his own details — a secret tunnel, a cave, a tower, whatever – to his maps, they become reality. Obviously, the Inquisition wants to investigate poor hapless Hassan (who will be doubly damned when it is learned that he is gay), but fortunately, Fatima, the Sultan’s favored concubine and Hassan’s childhood friend, learns what is happening and the two of them flee. Accompanied by a jinn (Vikram the Vampire – strangely transplanted to Iberia from Hindu India) they hatch a plan to escape to a legendary island, based on nothing more than legends and one of Hassan’s maps.

The Good

The characters themselves, however, are a delight. Fatima, our POV character is likeable and believable: We know she is clever, resourceful and stubborn, but she is also a concubine who has never left the palace and a teenager: she makes stupid mistakes and her cleverness is sometimes undone by a shut-in’s naivete or a teens lack of impulse control. The result is a very likeable, believable heroine. Hassan is more uneven; he is in many ways the bumbling professor or academic who forgets to put his pants on, but that portrayal is uneven: at times he comes across as sweet-but-clueless, at others just dumb. It also is a harder sell, since he is a commoner who spent a fair amount of his life living outside the city.

The Djinn Vikram is perhaps the most interesting character: shapeshifter, vampire and curmudgeon, clearly drawing from the story of Baital Pachisi most famously translated by Sir Richard Francis Burton as “Vikram and the Vampire.” I’m not sure what Wilson was alluding too by taking a Hindu legend (which, I am told, appears in her earlier work Alif the Unseen) and transporting him to Iberia, but as a character, he’s a really fun read.

So as a fantasy novel: beautiful prose, delightful, unusual characters, and a form of “magic” that is fresh and new. It’s almost magical realism in style and truly a good read — good enough that I went and picked up the author’s other work, and will keep doing so.

Alif the Unseen (Paperback edition, Grove Press 2013)

The Bad

On the other hand, Wilson made the choice to set her novel in *1491 Spain,* not a thinly drawn mythical or parallel world, and her story hinges upon the fall of Granada and the role of the Spanish Inquisition, at that time led by the infamous Torquemada.

Sadly, this just isn’t that world. At all.

I am not talking about little historical mistakes — confusing arquebusier with fusiliers – that wouldn’t exist for 200 years, misunderstanding what a rapier is, little clothing details that describe more of Spain in 1580 than 1480 — which may bug history nerds like me, but has little bearing on the story. Instead, these are issues that create a false narrative of history and a culture, in just the same way that Orientalists of the 19th and early 20th century used the Muslim world as the default “bad guys,” while always having examples of the noble exception (see the Victorian obsession, for example, with Saladin).

You see this novel’s villain, like so many set in Renaissance Spain before it, is the Inquisition! Yes, those creepy, torture-happy burner of witches, paranoid secret police and all-around baddies led by the insane Cardinal Torquemada.

Only, none of that is true.

G.-Willow-Wilson

Or rather, it is such a distortion of truth that seeing it in a serious, 2019 novel, is jarring. Remember by plot summary above, and then look at what happens if we remove the following problems:

1. Female Inquisitors

Our villain is the Lady Luz, a character who simply cannot exist in late medieval Spain. Certainly, the Order of St. Dominic had female “donats” – lay clergy who were not cloistered or had taken all of their vows, but the Dominicans, while leading the Inquisition, were not *synonymous* with it. There were actually precious few Inquisitors – sometimes as little as two per tribunal – and they were required to be priests and university educated in law – two traits that would immediately exclude our villainess, even if, women were expressly banned from holding any role in the Inquisition during this period.

I get this is a feminist fantasy novel, so the author wants a female villain, too. I would have just made the Lady a member of Queen Isabella’s (not exactly a nice or merciful woman) court. But the Inquisition is more dramatic. I could shrug a special envoy off with a wink and a nod, but the entire use of the Inquisition is, well…

2. Inquisitional Authority Over Muslims

There was no distinction in the newly unified Kingdom of Spain between secular and religious law in any meaningful way, and the reason for replacing the older medieval Inquisition with the Spanish Inquisition was to transfer power of the Inquisition to the Crown – something the Papacy was never happy about, but had little real power to prevent (as they would be reminded when German Lutheran soldiers in service of “His Most Catholic Majesty of Spain” would sack Rome in 1527).

However, while the Inquisition was a kind of secret police, particularly concerned with heresy, during the 15th century that specifically referred to lapsed conversion – Jews and Muslims who had converted to Christianity. This intensified after two royal decrees were issued (in 1492 and 1501 — both after our novel) ordering Jews and Muslims to choose baptism or exile. The Inquisition specifically did not oversee conversions, nor did it have any legal authority to investigate, try or judge Jews and Muslims who had not converted – so while modern people gulp when they hear “Spanish Inquisition” (or think of Monty Python), the simple fact is that there is no reason that Queen Isabella would be sending an inquisitor to Grenada until the city had surrendered, and its people had converted (and for *two generations* after this novel, Muslims were allowed to live in southern Spain without converting or being expelled).

For all the influence Torquemada himself wielded with Ferdinand and Isabella, and for all his paranoia regarding false converts weakening the moral character of the new kingdom of Spain, the Inquisition was a purely inward looking organization: It was not involved in diplomacy, military negotiations, etc. So, by the time an Inquisitor appeared on your door, a) you were part of Spain, b) you were Catholic, either by birth or by public conversion. If those two things were true, then things could get…well, see picture below.

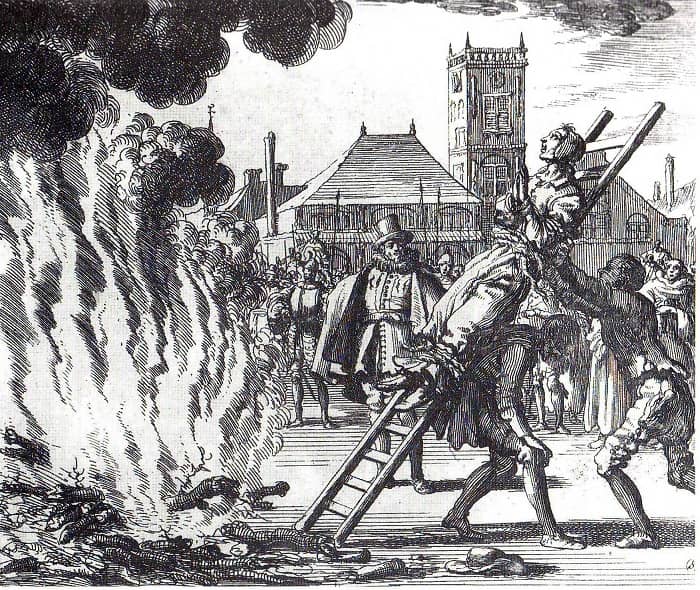

The “witch-burning” craze was sadly, just that, a mania that swept over parts of Europe,

Spain being no exception. Ironically, the Inquisition generally ruled *against* charges

of witchcraft — apostasy of converts were their preferred route to the stake.

3. Sorcery and Sodomy

Hassan is a gay man who works magic – both of which are things the Inquisition certainly investigated, both of which would get him killed in Christian Spain were his secret made public (or Moorish Spain, which the author does point out).

But, ironically, Torquemada himself did not believe in sorcery or witchcraft, calling it “superstition”, and not a single witch-trial was held during his control of the inquisition. In fact, the witch-hunt in Spain had much less intensity than in other European countries (particularly France, Scotland, and Germany), and there are only five known trials, all of which occurred in the late 17th century — two centuries after our events.

As to sodomy, there were trials for this, but the first sodomite to be convicted and burned was in 1572 – 100 years after this novel. Interestingly, of the 500 investigations for sodomy in the Inquisition’s history: Nearly all were between persons concerned the relationship between an older man and an adolescent by coercion. About 1/5 involved allegations of child abuse by adult men. The first sodomite was burned by the Inquisition in Valencia in 1572, and those accused included 19% clergy, 6% nobles, 37% workers, 19% servants, and 18% soldiers and sailors. As a rule, the Inquisition condemned to death only those sodomites over the age of 25 years. There are less than twenty cases, in 300 years, that involved a consensual, homosexual affair between adults.

Obviously, that doesn’t ~ and shouldn’t ~ make the Inquisition’s position towards gay relationships acceptable to modern people, but it means that, for all of what we think we know, the Inquisition was actually far less active in investigating and prosecuting those cases than most of Europe was in the early modern period, less tolerant of child abuse than the contemporary Ottoman Empire – and the prosecutions that did occur were generations after this novel is set.

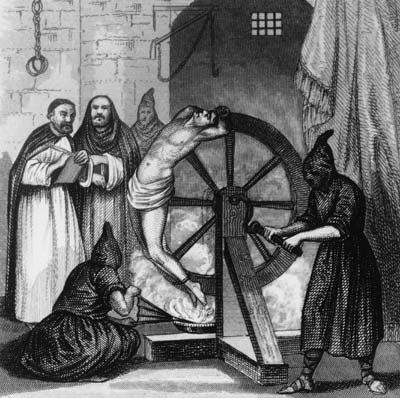

That’s going to hurt! The wheel, strapado and all of the other

horrible tools of torture were absolutely part of the Inquisitor’s

trade — but far more often used by secular authorities, who had

few restrictions on putting a subject “to the question.”

4. Use of Torture

Lady Luz has a personal set of torture tools that she carries with her and uses to get her own men to talk, making her something like the novel’s Darth Vader vis a vis Imperial officers, only with much nicer clothes.

This is simple nonsense.

Torture was employed in all civil and religious trials in Europe, and the Spanish Inquisition was decidedly no exception. However, as opposed to civil trials, it had very strict regulations regarding when, what, to whom, how many times, for how long and under what supervision it could be applied. The Spanish inquisition engaged in it far less often and with greater care than other courts, especially since, in most civil courts throughout Europe and the Muslim world, there was no restriction.

Torture was allowed only: “when sufficient proofs to confirm the culpability of the accused have been gathered by other means, and every other method of negotiation have been tried and exhausted.” It was stated by the inquisitorial rule that confession should only be extracted this way when all needed information was already known and proven. Confessions obtained through torture could not be used to convict or sentence anyone.

Further, Inquisitors were expressly prohibited to “maim, mutilate, draw blood or cause any sort of permanent damage” to the prisoner. A physician was required to be present, and “torment” could only be applied for 15 minutes. Further, only those charged with an inquisitorial crime could be tortured. The penalties for Inquisitors who violated these rules were themselves brutal.

So, the scenes where Luz tortures one of her mercenaries isn’t just as spurious and lurid as the Inquisition in a Poe story; it’s ludicrous. No soldier would stand there and let himself be subjected to torment, because the entire act was illegal. There is simply no reason a group of mercenary soldiers would feel a need to follow her orders and let one of their men be tortured, in the wilderness, for no reason other than the Inquisitor’s bit of pique. It’s cartoon villainy of an implausible villainess on an implausible mission.

But it’s not honest. It is a promulgation of the “Black Legend” – myths and rumors started in England and Germany for political purposes during the ongoing religious wars of the 16th and 17th centuries. The fact that the stereotype is now engrained in Anglophone literature does not make promulgating it OK.

You want witch-hunts, go to Germany — neither the Spanish nor the Italian Inquisitions were interested

Conclusion: Sometimes Secondary Worlds Work Better

In case this wasn’t clear:

- I really like this novel as a work of fiction, but find its historical presentation troubling, because it could have been so easily avoided.

- I don’t think Ms. Wilson had the slightest intent to stereotype or caricature anyone, and that’s clear in how she treats her characters, who are very carefully realized.

- No one in their right mind would celebrate the Spanish Inquisition. Let’s be clear: this is an organization that drove tens of thousands of Jews and conversos (those who had converted to Christianity) out of Iberia over the course of the 16th century, left Muslims with the choice of conversion or expulsion, suppressed literature, ended “non-productive” marriages, and did, indeed burn people at the stake. But of the 150,000 cases the Inquisition engaged in over 300 years, 75% ended in — acquittal; of the other 25%, most ended in fines, public penance or expulsion. Approximately, 1 – 2% of cases ended in execution, which would be about 3,000 put to death over just under 300 years, most during the late 16th and 17th centuries. This is significantly lower than the number of people executed exclusively for witchcraft in other parts of Europe during about the same time (estimated at c. 40,000–60,000). If we are going to make historical figures and institutions our fictional villains, we have some obligation to show the crimes they were actually guilty of, not the ones made up by their enemies.

- I don’t think the Catholic Church needs sensitivity readers…but in a time when we are pushing for representation, reconsideration and fighting stereotypes, maybe fiction editors do need to be basic fact-checkers, and the points I am making here can be found with little more than a Wikipedia check.

History rarely provides “good guys” and “bad guys” and the history of the Conquista and Reconquista provides a host of brutality, broken deals and false promises on both sides. The Spanish Inquisition in this novel is no more real, nor reflective of what the Inquisition’s role in the Reconquista was than Philip Pullman’s “Magisterium” is the modern Catholic Church, and Luz is no more reflective of an historical inquisitor than is Mrs. Coulter in those novels. The difference is, we know that the world of the Magisterium is a secondary world to our own — one possible way its institutions could have gone. Here we are led to believe this is how it was.

Wilson is one of a number of authors doing a beautiful job of mainstreaming and normalizing Muslim characters and settings in fiction. But it is problematic doing so while promulgating false historical narratives. Please, give us a more realistic presentation, a detailed Author’s Note at the end, or just make it a secondary world that is so obviously based on our own, but the names have been changed to protect the guilty. Guy Gavriel Kay has made an entire career at just this, and is probably blurring the line between Historical Fantasy and Low Fantasy. He’s absolutely one of my favorite writers.

Which is why, it is ironic that, next time, we’ll talk about why when his formula fails, it produces some of the most beautifully written, historically faithful, yet incredibly boring, fiction you can read…