The Weird of Oz gabs about Antiheroes

Antihero. A problematic term to begin with, its overuse has further watered it down. Anti- typically means to be in opposition or even to be the opposite; the antithesis of a position is the oppositional position.

Antihero. A problematic term to begin with, its overuse has further watered it down. Anti- typically means to be in opposition or even to be the opposite; the antithesis of a position is the oppositional position.

So, technically, one might interpret anti-hero to mean a villain. This is rarely, if ever, how the term is used; so what do we mean by an antihero?

Off the top of my head, without resorting to any dictionary definition, this is how I tend to picture an antihero: A person not serving any particular ideal or higher purpose, but generally self-serving, who, while going about his (or her) business in pursuit of fortune, power, pleasure, or whatever turns his crank, is suddenly confronted by a moral choice. And at that moment, not for any dogmatic or religious reasons, any creeds or codes, but simply because of some niggling inner compass — his conscience — he makes the choice that is least likely to offer personal gain, that involves self-sacrifice, that may in fact be fatal. He makes a heroic choice, the choice that allows us to continue to root for him as the hero-protagonist.

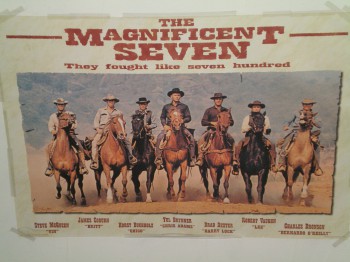

Think of the fallen samurai in The Seven Samurai or the lawless gunslingers in The Magnificent Seven. In both cases, when they learn that the threatened peasant village cannot really afford to pay them and that they are outnumbered five to one, they nevertheless decide to make a stand to protect the afflicted. No promise of financial reward and a very high probability of death — an option that the histories of these men would not suggest they would choose. They are neither knights nor saints. Yet they become heroes and, in some cases, martyrs. All appearances to the contrary, deep down they prove to be — when it really counts — good men. Or in that moment they become good men.

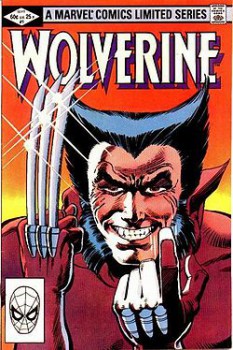

It has been fashionable to describe “gritty” characters as antiheroes, for example the comic-book character Wolverine. He crosses lines other squeaky-clean superheroes never would; he is more likely to kill a bad guy than to leave him tied up for the authorities to haul away to prison.

It has been fashionable to describe “gritty” characters as antiheroes, for example the comic-book character Wolverine. He crosses lines other squeaky-clean superheroes never would; he is more likely to kill a bad guy than to leave him tied up for the authorities to haul away to prison.

Yet his loyalty is never in doubt — he wears the uniform of an X-Man or an Avenger, so it is harder to pin my preferred interpretation of “antihero” onto him. And as the trend for gritty heroes in comics and then film gradually became the norm in the ‘80s and ‘90s, “antihero” all but lost its meaning and impact.

For a better example of an antihero — again from a western — think of Rooster Cogburn in True Grit. Or consider Huck Finn. Having been taught by his society’s cultural standards that to help his friend Jim escape slavery is tantamount to aiding and abetting theft (the stolen property being Jim himself), a sin that will send him to Hell, he resolutely chooses damnation.

“All right, then, I’ll GO to hell,” Huck declares as he tears up the letter he had written that would have betrayed Jim and — in Huck’s misguided thinking — absolved him of sin. “It was awful thoughts and awful words, but they was said. And I let them stay said; and never thought no more about reforming.” In so doing, he becomes one of the great heroes of American literature (and, ironically, redeems his soul).

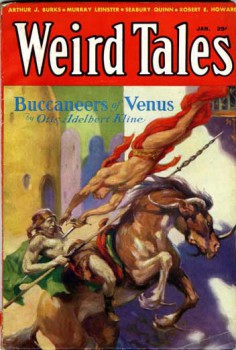

In sword and sorcery, the very template of the antihero is given by Robert E. Howard and his seminal character Conan. A self-serving barbarian, rogue, pirate, mercenary, with a bloodlust that is legendary, he becomes an antihero when he makes choices that indicate he does have a conscience.

One salient example is found in “The Scarlet Citadel.” Although one of the earliest Conan stories, first published in Weird Tales in 1933, chronologically it recounts one of the barbarian’s last adventures. Late in his career, Conan has become King of Aquilonia. Taken captive, he is offered a nice haul of treasure and his life, if he just agrees to leave. The alternative: the dungeon, torture, likely death.

One salient example is found in “The Scarlet Citadel.” Although one of the earliest Conan stories, first published in Weird Tales in 1933, chronologically it recounts one of the barbarian’s last adventures. Late in his career, Conan has become King of Aquilonia. Taken captive, he is offered a nice haul of treasure and his life, if he just agrees to leave. The alternative: the dungeon, torture, likely death.

In that moment, Conan shows himself a true king, rejecting the bribe and preferring death to the thought of betraying his adopted people. Not because of some inculcated doctrine of chivalry or some religious devotion (Crom could care less), but simply because at that moment, he realizes his subjects are more important to him than himself. They may never know of his sacrifice, but he will not be party to their oppression.

Because of decisions like this, we can think of Conan, despite his having slain hundreds, perhaps thousands, without remorse, as a good man. A hero not in the traditional sense, of course, because it is not a foregone conclusion that he would so act, as it might be for, say, a King Arthur or King Aragorn. Thus, an antihero.

True antiheroes (not just “gritty” types who get slapped with that appellation) tend to be the most interesting characters. Perhaps because they are more human, closer to us. Not vaunted above mortal man. We root for morally superior heroes, but they are at a remove from us. We realize that if we were confronted with some of those choices, we might be conflicted — we may wonder what we would truly choose, were our self-interest and self-preservation to be put to the challenge.

Antiheroes, not having a dogmatic creed or a god or higher power to make the choice clear for them or to offer succor in that choice, act from a more sympathetic, human place. And are all the more heroic for it.

Odds ‘n Ends:

I originally compiled these thoughts on the antihero for a brief introduction to a story of mine that was to appear in an anthology from Ricasso Press. Since that project was shelved a few years ago and, as far as I can ascertain from the web, Ricasso Press is no more, I am sharing them here.

The term alembic in the title of last week’s post “Oz’s Alembic: An Introduction” was recommended to me by my friend Frederic Durbin, who has made use of that word in his current novel-in-progress. I’ll explain the gestation of my new working title “The Weird of Oz” in my next post, because right now I need to get back to playing pirates (who often make good antiheroes) with my children.

Interesting…so any “every day” person can be an antihero…it can happen to anybody, and it just depends on what we do with that peasky thing known as “free will”. Thanks! I enjoyed the blog!

My take on it would be slightly different. To me an anti-hero is somebody who doesn’t conform to our standard expectations of what a hero ought to be, but is a hero nonetheless. Usually, he is a bad man, redeemed by the even more morally dubious world he inhabits. ‘The Man With No Name’ only ever acts out of self-interest, but the people against whom he pits himself are wickeder than he is – much the same could be said of Kane the Mystic Swordsman, Jerry Cornelius and Sam Spade. Context is everything.

Good points, Aonghus — also some great additional examples of antiheroes.

I noted that an antihero is “generally self-serving” and “in pursuit of fortune, power, pleasure, or whatever turns his crank.” You’re absolutely right that context plays a big role–that “the people against whom he pits himself are wickeder than he is.”

I think the only point I would question is whether each of these characters “only ever acts out of self-interest.” It seems to me that at some point there is a selfless decision the character makes, even if it is not dramatically obvious–hell, in the context of another time and place it might not even be notable or outside the norm. But each is influenced by his conscience in some way that brings in the term “hero,” even if it is embedded in “antihero.”

For example, Eastwood’s Man With No Name takes advantage of bloody rivalries between feuding families, pretending loyalty to both sides when in fact he is aligned with no one. Yet in one notable scene he risks giving up the game in order to help some innocent folks escape, even giving them money. When they ask him why, he simply replies, “Why? I knew someone like you once. There was no one to there to help. Now get moving.”

Ah, I thought Aonghus’ words were going to put it right, but they stopped just short! 🙂

This part is spot on “an anti-hero is somebody who doesn’t conform to our standard expectations of what a hero ought to be, but is a hero nonetheless” but then things go a little off in my opinion. I contend that anti-hero — contrary to your astute observation that an anti-hero must obviously be a clever label for the villain — is not the literal opposite of the word ‘hero’ but the concept or [i]expectation[/i] of hero.

That “somebody who doesn’t conform to our standard expectations of what a hero” is is still heroic…while a villain remains villainous. These heroes that are anti/opposite what we expect/anticipate our heroes to be are the clumsy, nerdy, nonathletic, generally inept members of society who naturally do ‘what is right’ but either fail or are so insignificant in their attempts that they don’t register on the heroic-seeking social psyche. Charlie Brown, the nerds from Revenge of the Nerds fame…it’s late and my eyes are burning while my brain is not, but essentially these anti-heroes are those folks who aren’t muscular, large, impressive, beautiful, thorough, crack shots, martial artists, or in any other way glorious — they’re the weak, unnoticed, unheeded who step up and try to hold the door only to have it slammed on their fingers, the ignored and uncoordinated who try to defend the dignity of another being or at least soften the uncouthness of another only to be derided and shoved aside.

Those are the true anti-heroes, for though they strive to be heroic for the same reasons as our ‘normal/regular/standard’ heroes, they most often fail due to inadequacies of some nature, their infrequent successes not enough to catapult them to ‘hero’ appellations.

I whole-heartily agree that today this label is vastly misused, primarily for the reason I state above, but I also find merit in your observations on Wolverine, Nick, and on your assertion that ‘gritty’ does not equal ‘anti-hero’ even if it meant what I don’t believe it does.

As for what to call these self-serving ‘accidental’ heroes? Why, Lord Byronic heroes of course http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Byronic_hero …for they are those who typically lack the quality of heroic virtues while anti-heroes are those we find lacking in heroic physique and persona.

I believe this distinction necessary, this clarity of heroic roles desirable, though I deem the tales of true anti-heroes anti-climactic and ultimately boring in any quantity or length. And I’m a realist — it’s much easier on today’s readers, marketers, actors and even writers to use/say/write/think antihero than Byronic hero, so this distinction is doomed to dismissal.

Great post, Nick.

Curiously, a term I never see being used is the “antivillain”, although you could define it by simply reversing part of your “antihero” definition. Someone like Darth Vader or Magneto, who begins with a moral code and a clear intention to selflessly help others but, when presented with that moral choice, opts to hurt innocent people in order to achieve his or her goals.

My bad. I was happy enough with my first sentence, as I couldn’t think of an anti-hero who didn’t fulfil this definition. Then I tried to narrow it down a bit. I guess saying the anti-hero comes up against people who are wickeder than him, automatically implies that he has SOME sort of code? That it’s still relative?

I know I’m reaching here (especially as Jason’s comment about Charlie Brown et al is bang on) but….

Michael, your anti-villain idea is incredibly useful. Did you find it somewhere, or come up with it yourself? A blog post about anti-villains is already writing itself in my head, and I’d like to attribute the term properly.

Jason, I found your thoughts on the Byronic hero enlightening–thanks for the link! Following that back further to the wiki on antihero, I noted with interest the claim that the first use of the term “antihero” was in regard to Don Quixote. That example would certainly be more in line with your definition (someone possessing heroic principles but who is wholly ineffectual in enforcing them), although you’re also right that today this is not what most people use the term to denote. As you noted, I was addressing the popular contemporary understanding of the term.

Michael, I agree with Sarah that your “antivillain” idea is intriguing, and those are two very compelling characters you cite. In both their cases it may also be added that their early moral codes, warped and corrupted though they have become, do occasionally shine through and offer opportunity for redemption. Darth Vader redeems himself at the very last, of course, in turning on the Emperor. Magneto is a complex character who in recent years has been allied with the X-Men nearly as often as he has opposed them.

I thought this post might generate some interesting discussion, and I was not disappointed.

Anti-Villain

WoW, Mary – that was an amazing link! My eyes are still crossed there’s so much there to cross-reference and read.

@Nick, I’d bet many of your posts will generate interesting exchanges 🙂

[…] The Weird of Oz Gabs about Antiheroes […]