The King of Asgard: Jack Kirby’s Thor

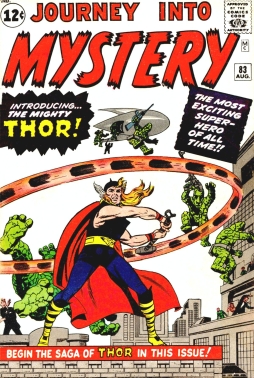

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder.

Journey Into Mystery first appeared in 1952, one of a number of anthology titles from publisher Martin Goodman’s line of comic books. Over the years, the title featured a lot of short horror, fantasy, and science fiction tales, many of them collaborations between editor/scripter Stan Lee and artists like Steve Ditko and Jack Kirby. Until 1962. At that point Goodman’s comics were beginning to change direction, following a revival of interest in the super-hero genre. A team book, The Fantastic Four, had taken off. A solo book had followed, The Incredible Hulk. Heroes would now be his company’s main product, and the line would soon come to be known as Marvel Comics. The horror anthology books would be taken over by recurring super-hero characters, and Journey Into Mystery would be the first of the bunch. So with issue 83, in August 1962, in a story credited to Stan Lee and artist Jack Kirby, it introduced its new lead: the mighty Thor, Norse god of thunder.

Donald Blake, a physician with a leg injury, takes a vacation in Norway. There, he stumbles across an invasion of the planet Earth by Stone Men from Saturn. Fleeing the aliens, and losing his cane in the process, Blake stumbles into a cave, where he finds a gnarled walking-stick lying on an altar-like stone. In frustration, he slams the stick into the cave wall and is transformed into Thor, vastly strong and able to summon storms at will. He defeats the Stone Men and embarks on an increasingly fascinating series of adventures.

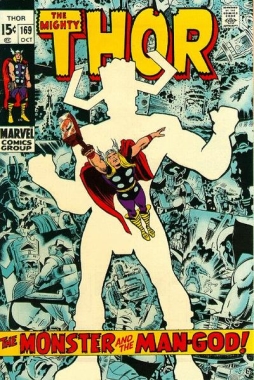

Kirby drew the book sporadically between issues 83 and 100, then consistently from 101 through to the point where he left Marvel — number 179, with a fill-in by Buscema on the issue before. While, as I’ve said before, it’s difficult to make definitive statements about who did what creatively in the early Marvel comics, it’s safe to say that Kirby was the primary creative force here as with most of his other books. The Marvel method meant that he was structuring and probably plotting stories, as well as suggesting dialogue beats. I think Thor represented one of his great accomplishments, a working-out of some of his major themes; evolution, myth, life, and death. It’s not only an anticipation of his later New Gods series, but a powerful work of children’s literature in its own right — and, like much of the best children’s literature, it can be read for pleasure by receptive adults as well.

Let’s look more closely at the overall chronology of Kirby’s work on the title. Issues 83 through 89 were plotted by Lee (probably in collaboration with Kirby), and drawn by Kirby with inks by Joe Sinnott on the first issue and Dick Ayers thereafter. Scripts came from Larry Lieber. The stories weren’t that powerful at first, and elements of myth entered the series very slowly. After fighting aliens in the first issue, Thor fought communists in the second — and then his brother, Loki, god of mischief, in the third. Loki’s not referred to as Thor’s brother in this story, but the first page introduces Asgard, a city on an island floating in a starscape and connected to Earth by Bifrost, the Rainbow Bridge. The next story, in which Thor fights a time-traveler, introduces Thor’s father Odin (depicted by Kirby with two eyes). The pieces are slowly coming together; but the next issue is another tussle with evil commies, then another fight with Loki, then a fight with gangsters.

Let’s look more closely at the overall chronology of Kirby’s work on the title. Issues 83 through 89 were plotted by Lee (probably in collaboration with Kirby), and drawn by Kirby with inks by Joe Sinnott on the first issue and Dick Ayers thereafter. Scripts came from Larry Lieber. The stories weren’t that powerful at first, and elements of myth entered the series very slowly. After fighting aliens in the first issue, Thor fought communists in the second — and then his brother, Loki, god of mischief, in the third. Loki’s not referred to as Thor’s brother in this story, but the first page introduces Asgard, a city on an island floating in a starscape and connected to Earth by Bifrost, the Rainbow Bridge. The next story, in which Thor fights a time-traveler, introduces Thor’s father Odin (depicted by Kirby with two eyes). The pieces are slowly coming together; but the next issue is another tussle with evil commies, then another fight with Loki, then a fight with gangsters.

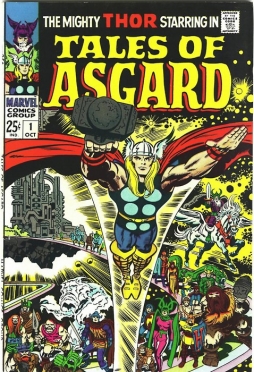

The stories are short — ten or thirteen pages, with the rest of an issue padded out with back-up tales. They mostly treat Thor as a standard-issue super-hero, with Blake’s nurse, the bland Jane Foster, there to create the typical super-heroic love triangle, drawn to hero and secret identity alike. So the stories suffer from the attitudes of their times, in terms of the depiction of women. They suffer even more from the unintentionally comedic anti-communism of the early Marvel books. For almost a year and a half, there didn’t really seem to be anything particularly distinguished about Thor. Kirby himself left the book for several issues, during which Loki was established as Thor’s brother. Kirby came back for issue 93 (in which Thor fought a Chinese communist super-villain named the Radioactive Man), and more permanently starting in issue 97. Although he didn’t draw the lead stories for the next three issues, he did contribute a new ongoing back-up feature — one that would lead the way forward for the whole book.

That new back-up was a series of five-page short stories called “Tales of Asgard.” The “Tales” would run through to issue 145, with each of them drawn by Kirby and scripted by Lee. They loosely retold Norse myths, effectively creating a background for Thor’s adventures. Kirby’s sensibility grabbed hold of the old legends, changing them into something distinctively his. The series soon shifted to telling tales of Thor’s boyhood, then with issue 117 began telling long serial stories in which Thor adventured around Asgard — starting with a tale in which he captained a crew of Norse ‘argonauts’ seeking out a hidden foe of the gods. The back-up was exploring the fantastic world implied by the existence of the gods and Kirby responded with increasing exuberance to the story potential he’d found. Slowly, the main feature would come to reflect this, developing a new emphasis on mythology — and re-imagining myth for the modern age.

That new back-up was a series of five-page short stories called “Tales of Asgard.” The “Tales” would run through to issue 145, with each of them drawn by Kirby and scripted by Lee. They loosely retold Norse myths, effectively creating a background for Thor’s adventures. Kirby’s sensibility grabbed hold of the old legends, changing them into something distinctively his. The series soon shifted to telling tales of Thor’s boyhood, then with issue 117 began telling long serial stories in which Thor adventured around Asgard — starting with a tale in which he captained a crew of Norse ‘argonauts’ seeking out a hidden foe of the gods. The back-up was exploring the fantastic world implied by the existence of the gods and Kirby responded with increasing exuberance to the story potential he’d found. Slowly, the main feature would come to reflect this, developing a new emphasis on mythology — and re-imagining myth for the modern age.

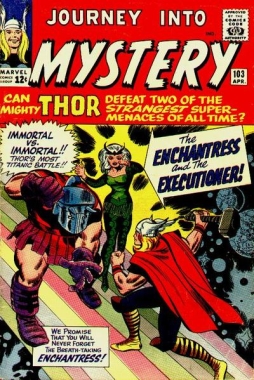

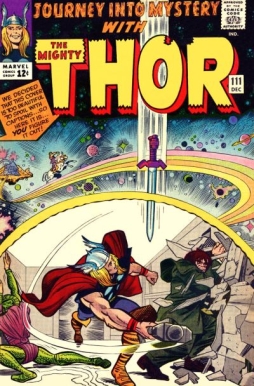

Thor fought an Asgardian duo, the Enchantress and the Executioner, in issue 103. Then the next issue saw a spectacular battle pitting Thor, Odin, and Balder (briefly introduced, as Thor’s friend, in Tales of Asgard in issue 102) against a storm giant and the fire giant Surtur. It was the series’ early high point, but the next few issues mostly saw Thor again fighting mortal super-villains: Mister Hyde, the Cobra, Magneto, and the Grey Gargoyle. Then number 111 saw Thor’s battle with Hyde and the Cobra paralleled with an extensive sub-plot following Balder in Asgard, questing at Odin’s behest to find an item to help Thor; the cover, showing Balder’s sword piercing the rainbow dividing Asgard from Earth, seemed to promise a collision of worlds, if not the penetration of the mundane by the divine. And indeed, from that point on, there seemed to be a struggle in the series between the Asgardian story elements and the more pedestrian plots revolving around fighting communism or Thor’s romance with Jane Foster. Asgard grew more and more prominent, and more distinctive visually.

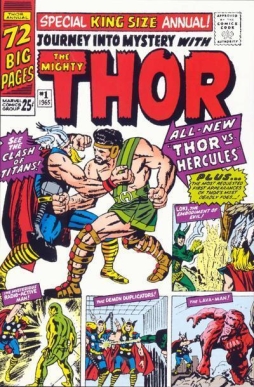

The stories grew longer, sprawling over three and four issues, flowing one into the other. An annual (extra-sized special issue) in 1965 introduced Hercules and the Olympian gods. The title of the book changed to The Mighty Thor with number 126, which saw Hercules return to kick off a plot pitting him and Thor against Pluto, imagined as a diabolic lord of hell. By this time, Kirby was in his full glory; the month the book was renamed was the same month the Fantastic Four were meeting Galactus over in their title. You could see a stretching of Kirby’s art, narrative style, and thematic interests in both books.

The stories grew longer, sprawling over three and four issues, flowing one into the other. An annual (extra-sized special issue) in 1965 introduced Hercules and the Olympian gods. The title of the book changed to The Mighty Thor with number 126, which saw Hercules return to kick off a plot pitting him and Thor against Pluto, imagined as a diabolic lord of hell. By this time, Kirby was in his full glory; the month the book was renamed was the same month the Fantastic Four were meeting Galactus over in their title. You could see a stretching of Kirby’s art, narrative style, and thematic interests in both books.

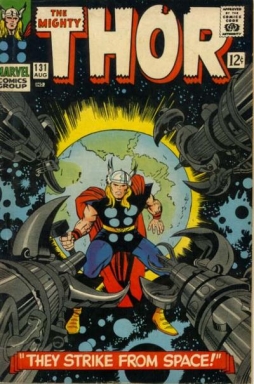

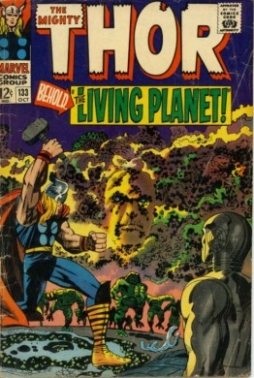

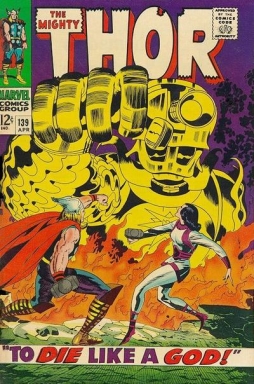

After dealing with the Olympians, Thor goes on to fend off another alien invasion, leading to spectacular extraterrestrial adventures and, finally, the introduction of Ego, the Living Planet. Legendry and super-science fuse. In Kirby’s mythopoeic vision, there’s no distinction between the archaic and the futuristic. Returning to Earth, Thor finds Jane Foster’s been abducted by the agents of a being called the High Evolutionary, a scientist who’s evolved himself to a godlike state of advancement. The Evolutionary has also evolved animals into human-like New Men and taught them the ways of chivalry — and accidentally created a devilish antagonist, the Man-Beast. Gods, knights, and scientist-heroes; in Kirby’s imagining, it’s all one. From that fight, Thor goes back to Asgard to try to elevate Jane Foster to godhood. Intriguingly, the attempt fails. Foster can’t handle the sheer fantasy of Asgard, the trolls and gods and magic. She leaves the series, and is immediately replaced by the far more interesting character of Sif, Thor’s wife in myth, here imagined as a raven-haired warrior goddess.

It’s difficult to overstate Kirby’s visual power in these comics. His Asgard has become a mix of fairy tale and science fiction, a glittering city from no one point in time. His design sense is stunning; Midas-like, it transmogrifies all his imaginings into a coherent world. His storytelling is literally awesome. Characters emote, dramatic and even operatic, their stances and poses not just expressive, but dynamic. They fight, brawling across pages with verve and imagination, their battles perfect culminations of the themes of their stories. Panel and page compositions almost force the reader’s eye to move when and how Kirby wants. A strong sense of perspective and the three-dimensionality of a scene comes out in his extreme foreshortening and clever use of the z-axis — things hurtle out of frame toward the reader. We are always grounded in place, following the action through alien planets and godly realms: Kirby’s art shows us much, but leads us also to imagine the places as he does. It’s almost trite to talk about the energy in Kirby’s art, but the effect is inescapable. The headlong rush of conflict-filled story, deftly told, sparks something in the reader.

It’s difficult to overstate Kirby’s visual power in these comics. His Asgard has become a mix of fairy tale and science fiction, a glittering city from no one point in time. His design sense is stunning; Midas-like, it transmogrifies all his imaginings into a coherent world. His storytelling is literally awesome. Characters emote, dramatic and even operatic, their stances and poses not just expressive, but dynamic. They fight, brawling across pages with verve and imagination, their battles perfect culminations of the themes of their stories. Panel and page compositions almost force the reader’s eye to move when and how Kirby wants. A strong sense of perspective and the three-dimensionality of a scene comes out in his extreme foreshortening and clever use of the z-axis — things hurtle out of frame toward the reader. We are always grounded in place, following the action through alien planets and godly realms: Kirby’s art shows us much, but leads us also to imagine the places as he does. It’s almost trite to talk about the energy in Kirby’s art, but the effect is inescapable. The headlong rush of conflict-filled story, deftly told, sparks something in the reader.

Yet Kirby’s Thor is usually given second place to his Fantastic Four work from the same era. Why? What distinguishes the two books? I don’t think it’s quality. I think Kirby’s work on Thor is every bit as good as his work on FF, perhaps better. But there are some significant narrative differences. And I suspect that the collaborative process didn’t help Thor as much as it did the other book.

The story differences first. Thor was one of the first of the Marvel books, and you can’t help but notice that what became the Marvel formula for character isn’t fully developed. Most Marvel characters are alienated from society, and specifically alienated by the nature of their powers or their state as a super-hero. They have a crushing weight of responsibility, like Spider-Man or Doctor Strange, or their power is a curse they’d rather be rid of, like the Hulk, or it simply makes them outcasts by nature, like the X-Men. There isn’t much of that in Thor. In fact, the nature of his dual identity — Blake and Thor are two physically and (mostly) mentally distinct characters — simply tends to remove Thor from the everyday realm. Blake seems to have less and less of a reason for being as the book moves along; why would we want to read about him when we can read about Thor and Asgard and outer space? It’s no surprise that Blake is an increasingly vestigial presence in the book as Kirby’s stories grow more expansive.

The story differences first. Thor was one of the first of the Marvel books, and you can’t help but notice that what became the Marvel formula for character isn’t fully developed. Most Marvel characters are alienated from society, and specifically alienated by the nature of their powers or their state as a super-hero. They have a crushing weight of responsibility, like Spider-Man or Doctor Strange, or their power is a curse they’d rather be rid of, like the Hulk, or it simply makes them outcasts by nature, like the X-Men. There isn’t much of that in Thor. In fact, the nature of his dual identity — Blake and Thor are two physically and (mostly) mentally distinct characters — simply tends to remove Thor from the everyday realm. Blake seems to have less and less of a reason for being as the book moves along; why would we want to read about him when we can read about Thor and Asgard and outer space? It’s no surprise that Blake is an increasingly vestigial presence in the book as Kirby’s stories grow more expansive.

There’s a theory that Thor was an attempt by Marvel to create a Superman figure for their hero line — someone who represented nobility and power at once. Certainly it’s been said that Thor’s red cape and overall blue-and-red-with-bits-of-yellow colour scheme recalls the Last Son of Krypton (though I find the design also recalls this illustration of a valkyrie by Arthur Rackham), just as some of the more delightful Tales of Asgard are stories of Thor as a child, recalling Superboy. But the transformation between alter egos in a flash of lightning is much more reminiscent of Fawcett’s Captain Marvel, another myth-based hero. Marvel was the more popular character through much of the Golden Age of comics, and his title had only relatively recently been discontinued; given what the Goodman line of comics was ultimately named, one wonders if the Captain Marvel character was on somebody’s mind.

At any rate, Thor doesn’t just take a sense of good and evil as the basis for his behaviour in the way other Marvel characters do. He moves in a divine world where good and evil are real things. His father is an omnipotent sky-god, the source of morality. Tonally, that’s different from the rest of the line, and particularly FF, where the characters are exploring the uncertain universe and coming to understand the strangeness around them. That’s not to say that good and evil are particularly complex in Silver Age Marvel, but there’s a bedrock certainty in Thor that gives it a distinctive feel.

At any rate, Thor doesn’t just take a sense of good and evil as the basis for his behaviour in the way other Marvel characters do. He moves in a divine world where good and evil are real things. His father is an omnipotent sky-god, the source of morality. Tonally, that’s different from the rest of the line, and particularly FF, where the characters are exploring the uncertain universe and coming to understand the strangeness around them. That’s not to say that good and evil are particularly complex in Silver Age Marvel, but there’s a bedrock certainty in Thor that gives it a distinctive feel.

It’s also a narrative issue. Odin can resolve any difficulty or battle, a literal deus ex machina. The ‘problem of evil’ then becomes a dramatic problem: why does Odin let bad things happen? Kirby and Lee find a number of ways around that — lapses in his omniscience, a desire to test his son, the need to restore his power through the ‘Odinsleep’ during which all manner of terrible things may happen, or simply conflict between Odin and Thor.

All these narrative choices have some interesting ramifications for Odin as a basis for morality. Arguably, bringing in the Olympian gods (with the implication of other pantheons beyond them) implies that Odin’s not all-powerful. Certainly towards the end of Kirby’s run, it’s said that Galactus, the cosmic destroyer of worlds introduced in Fantastic Four, is Odin’s equal: in a sense, his shadow. Odin’s frequent conflicts with Thor take on an archetypal, Oedipal overtone; Odin’s authority is debatable, his understanding perhaps limited, his verdicts arbitrary even when just. Thor’s recurring conflicts with his father echo the generational clash of the moment of these stories’ publication: Odin’s disapproval of an Asgardian marrying a mortal maybe goes even further.

All these narrative choices have some interesting ramifications for Odin as a basis for morality. Arguably, bringing in the Olympian gods (with the implication of other pantheons beyond them) implies that Odin’s not all-powerful. Certainly towards the end of Kirby’s run, it’s said that Galactus, the cosmic destroyer of worlds introduced in Fantastic Four, is Odin’s equal: in a sense, his shadow. Odin’s frequent conflicts with Thor take on an archetypal, Oedipal overtone; Odin’s authority is debatable, his understanding perhaps limited, his verdicts arbitrary even when just. Thor’s recurring conflicts with his father echo the generational clash of the moment of these stories’ publication: Odin’s disapproval of an Asgardian marrying a mortal maybe goes even further.

These things perhaps make the book less inherently accessible than Fantastic Four. But I think there were also some aspects of the collaborative process that were a problem. To start with, I don’t think the colouring of the book was as impressive as the eye-popping colour work on Fantastic Four. I want to be careful here, since almost all of the Thor books I’ve seen are reprints, with reproduced colours. And it’s not as though the colours (the colorist is uncredited) are necessarily bad. But I find overall the book isn’t as bright as Fantastic Four; it’s a little muddier, a little less flashy.

A greater problem is the inking. When Kirby returned to the book, his inker for a dozen or so issues was Chic Stone, who had a nice sleek line. Starting with 113 (and for almost all the ‘Tales of Asgard’ features), though, Kirby was inked by Vince Colletta. Colletta was widely regarded as a journeyman inker who was the man to turn to if a book needed to be finished quickly. In some ways, that’s unfair. Colletta had his virtues, bringing a nice feathery linework that created a sense of texture and worked well with the fantasy elements of Kirby’s stories. But at the same time, his inking didn’t always capture the dynamism of Kirby’s art. Worse — and the reason why I dislike Colletta on Kirby — he would often simplify Kirby’s drawing, leaving out details and sometimes whole figures. That changed the composition of the images. Having seen (reproductions of) a few pages of original Kirby pencils side-by-side with Colletta’s finished inks, I find when I read Kirby’s Thor that I’m always wondering what Colletta didn’t draw.

A greater problem is the inking. When Kirby returned to the book, his inker for a dozen or so issues was Chic Stone, who had a nice sleek line. Starting with 113 (and for almost all the ‘Tales of Asgard’ features), though, Kirby was inked by Vince Colletta. Colletta was widely regarded as a journeyman inker who was the man to turn to if a book needed to be finished quickly. In some ways, that’s unfair. Colletta had his virtues, bringing a nice feathery linework that created a sense of texture and worked well with the fantasy elements of Kirby’s stories. But at the same time, his inking didn’t always capture the dynamism of Kirby’s art. Worse — and the reason why I dislike Colletta on Kirby — he would often simplify Kirby’s drawing, leaving out details and sometimes whole figures. That changed the composition of the images. Having seen (reproductions of) a few pages of original Kirby pencils side-by-side with Colletta’s finished inks, I find when I read Kirby’s Thor that I’m always wondering what Colletta didn’t draw.

(As a contrast, here’s an appreciation of Colletta by Eddie Campbell, along with a rebuttal by Mark Evanier, and here’s a balanced overview of his strengths and weaknesses from Erik Larsen.)

Kirby’s last few issues were inked by comics veteran Bill Everett, and while Everett seemed at first to have some issues aligning his style with Kirby’s sense of anatomy, I found overall his work was a real step up. The dynamism of the pencils seems to come through more directly and there’s a sheen to the linework that recalls Joe Sinnot inking Kirby on FF. Everett seemed better able to follow Kirby into partial abstraction, into the distinctive ‘krackle’ of black energy that might outline a figure, or into the exuberant designs of everyday items that acquire a kind of strangeness by being seen through Kirby’s eyes. I can’t help but think Thor would’ve been a better book with Everett (or for that matter, Stone) inking all the way through.

Kirby’s last few issues were inked by comics veteran Bill Everett, and while Everett seemed at first to have some issues aligning his style with Kirby’s sense of anatomy, I found overall his work was a real step up. The dynamism of the pencils seems to come through more directly and there’s a sheen to the linework that recalls Joe Sinnot inking Kirby on FF. Everett seemed better able to follow Kirby into partial abstraction, into the distinctive ‘krackle’ of black energy that might outline a figure, or into the exuberant designs of everyday items that acquire a kind of strangeness by being seen through Kirby’s eyes. I can’t help but think Thor would’ve been a better book with Everett (or for that matter, Stone) inking all the way through.

Personally, though, I suspect the biggest difference between Thor and Fantastic Four is Stan Lee, and how Lee approached the stories. It’s often said that Lee brought a lightness of touch that humanised Kirby’s stories, which helped the Marvel books stand out. I don’t necessarily agree with that. Or, more precisely, I think the chemistry of the two men worked for Fantastic Four. But I can’t see how the grandeur of Kirby’s Fourth World books would have been improved by Lee’s scripting, and I think Thor is in the same boat.

Lee had good moments on the book. Most notably, I think, he developed an amusing pseudo-Elizabethan dialect for the Asgardian characters. That was a nice touch, even if it didn’t sound much like actual period language. Some readers have characterised the dialogue as ‘Shakespearean,’ but Lee’s got nothing of the distinctive Shakespearean wit and fluent wordplay. It’s much more like the simple style of the King James Bible. Either way, the speech Lee put into the mouths of gods was speech that recalled both the most canonical poet in the language, and the language that most English-speakers traditionally thought of when thinking of the divine. Of course Thor’s speech had an Elizabethan tinge. You wouldn’t have thought of it without reading it for yourself, but once you do read it, you realise it could hardly be anything else.

Lee had good moments on the book. Most notably, I think, he developed an amusing pseudo-Elizabethan dialect for the Asgardian characters. That was a nice touch, even if it didn’t sound much like actual period language. Some readers have characterised the dialogue as ‘Shakespearean,’ but Lee’s got nothing of the distinctive Shakespearean wit and fluent wordplay. It’s much more like the simple style of the King James Bible. Either way, the speech Lee put into the mouths of gods was speech that recalled both the most canonical poet in the language, and the language that most English-speakers traditionally thought of when thinking of the divine. Of course Thor’s speech had an Elizabethan tinge. You wouldn’t have thought of it without reading it for yourself, but once you do read it, you realise it could hardly be anything else.

But I still think that Lee’s sensibility did not on the whole lend itself to the book. His reflexive self-mockery, his instinct for lightness, sometimes works, but sometimes does not. I think he struggles in handling the central themes of the stories, the matters of life and death and myth which fill Kirby’s work. He doesn’t consistently find a way for his dialogue to get across the grandeur of the tales. His approach lent itself to Fantastic Four, but I don’t think it clicked on Thor. The characters were so different from the Fantastic Four. Lee could handle the easy contrasts in the dialogue of the FF and their villains and enemies, but the Asgardians all had similar speech patterns, a similar hauteur. The opportunities for light-hearted banter were much rarer.

Still, I think Thor compares well with The Fantastic Four. It may not be everything that it could have been, but the further it goes along, the more the themes of Kirby’s stories come to resonate, perhaps ultimately more so than on FF. He handles some surprisingly deep ideas and, for someone not known for his craft as a writer, shows a deft sense of structure in the way he brings them out.

Still, I think Thor compares well with The Fantastic Four. It may not be everything that it could have been, but the further it goes along, the more the themes of Kirby’s stories come to resonate, perhaps ultimately more so than on FF. He handles some surprisingly deep ideas and, for someone not known for his craft as a writer, shows a deft sense of structure in the way he brings them out.

Look at the basic set-up of the book. At first, the use of Norse myth seems haphazard. Odin has two eyes. Thor is a young man, perhaps barely out of his teens, if that. And he has a code of behaviour much more like an idealised medieval knight than a Viking. Rather than the small family and near-family group of Æsir one finds in the Eddas, Kirby imagines Asgard as a city filled with gods. But who says Thor can’t be a young man? Or, for that matter, have blonde hair? Is his heroism really different from the mythic Thor, the protector of mankind? Kirby’s re-imagining works. It makes for great stories. And it has the mythopoeic sense, the feel of something true and profound clothed in a fiction. A myth almost by definition lives in its retellings, and Kirby’s retelling of Norse myth is one of the greatest I know.

But there’s more than that going on. There’s a syncretic aspect to the myths in Kirby’s Thor, something clear not only in the appearance of the Olympian gods, but in the basic concept of the series. The nature of the union of Thor and Don Blake was cleared up, mostly, in issue 159, when we learn Odin sent Thor to Earth and created Donald Blake in order to teach the thunder god humility. So, in other words, two Jews used a Norse mythic structure to tell a story in which a divine father sends his firstborn son to earth to experience humility; there, the son becomes incarnated as a man, both fully human and fully divine, and comes into conflict with his great rival, the lord of evil. Who is depicted with a pair of horns on his forehead.

But there’s more than that going on. There’s a syncretic aspect to the myths in Kirby’s Thor, something clear not only in the appearance of the Olympian gods, but in the basic concept of the series. The nature of the union of Thor and Don Blake was cleared up, mostly, in issue 159, when we learn Odin sent Thor to Earth and created Donald Blake in order to teach the thunder god humility. So, in other words, two Jews used a Norse mythic structure to tell a story in which a divine father sends his firstborn son to earth to experience humility; there, the son becomes incarnated as a man, both fully human and fully divine, and comes into conflict with his great rival, the lord of evil. Who is depicted with a pair of horns on his forehead.

It’s remarkable, but more remarkable is that somehow it works. There’s a point in issue 151, in battle with an opponent created by Odin, when Thor even thinks “My father! My father! Why hast thou forsaken me?” — echoing the words of Christ on the cross. Rather than feeling contrived or out-of-place, it feels natural; it’s one place where Lee’s dialogue, much as it may tread the edge of hokiness, does get at something in the core of the story. From this perspective, the use of Hercules — who according to myth is also part mortal and part god — is natural, an obvious counterpart to the humanised Thor. And, in fact, ultimately Thor joins with him to fight Pluto, imagined as the evil ruler of a netherworld of punishment.

At first glance, moving from the conflicts of gods to battles against mortal super-villains, even if they happen to be powered by divine intervention, seems like it ought to be an incongruous shift in tone. But, reading the run as a whole (which is admittedly not necessarily the way it was intended to be read) the contrast actually comes to feel appropriate. The mortal gangsters and thugs are petty, yes, but so are their motivations; greed, lust for power, and the like. By contrast, Thor’s an idealist. He can’t help it. That’s his world. It’s a world without basic realism; as thunder god, Thor’s a walking incarnation of the pathetic fallacy. But then Kirby’s essential approach has little to do with realism and everything to do with the truth of myth.

At first glance, moving from the conflicts of gods to battles against mortal super-villains, even if they happen to be powered by divine intervention, seems like it ought to be an incongruous shift in tone. But, reading the run as a whole (which is admittedly not necessarily the way it was intended to be read) the contrast actually comes to feel appropriate. The mortal gangsters and thugs are petty, yes, but so are their motivations; greed, lust for power, and the like. By contrast, Thor’s an idealist. He can’t help it. That’s his world. It’s a world without basic realism; as thunder god, Thor’s a walking incarnation of the pathetic fallacy. But then Kirby’s essential approach has little to do with realism and everything to do with the truth of myth.

Look at the High Evolutionary storyline. Myth is fused with science; the men of the future, the New Men, learn behaviour from the moral codes of legend and story. But the gods of the future are trapped by the old stories as well, bringing evil into the world and causing their own downfall. Kirby’s fascinated by evolution; here that fascination struggles with a fascination for myth, and the result is a stunning adventure story with something new and surprising around every corner. And a touch of the elegaic; evil will always recur. In the “Tales of Asgard,” Kirby had depicted Ragnarok, the twilight of the gods, and that sense of inevitable doom came increasingly to the fore of the stories.

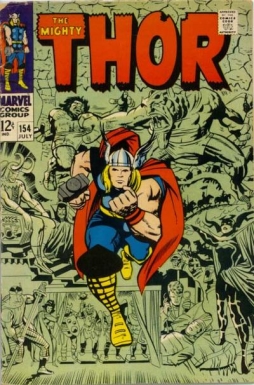

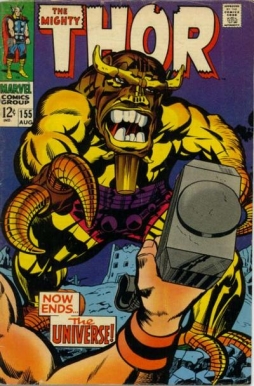

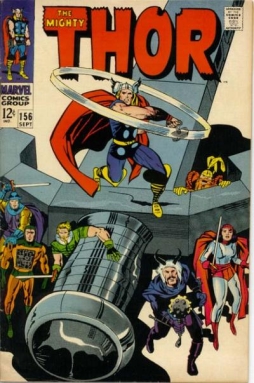

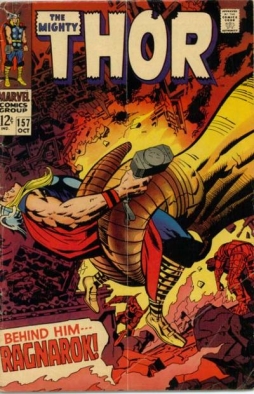

Maybe Kirby’s best work on Thor came with the Mangog storyline, running from 154 through 157. It’s an epic saga about struggling when death is inevitable; about the need to struggle. It begins with Hela, goddess of death, tempting Thor to forsake the world for Valhalla; he refuses, and later encourages some counter-cultural youths to take up a life of activism: “Tis not by dropping out — but by plunging in — into the maelstrom of life itself — that thou shalt find thy wisdom! There be causes to espouse!! There be battles to be won! … Yea, thou mayest drop out fore’er — once Hela herself hath come for thee!” But the important plot point of that first part of the story sees a minor villain named Ulik freeing a monstrous evil force named Mangog from his ancient imprisonment, at which point Mangog sets out to destroy Asgard and bring about Ragnarok. We eventually learn that Mangog is an old enemy of Odin’s, a collective entity, the embodiment of an ancient dying race, with all the power of a billion billion beings. Now he wants only to bring about the end of all that is.

Maybe Kirby’s best work on Thor came with the Mangog storyline, running from 154 through 157. It’s an epic saga about struggling when death is inevitable; about the need to struggle. It begins with Hela, goddess of death, tempting Thor to forsake the world for Valhalla; he refuses, and later encourages some counter-cultural youths to take up a life of activism: “Tis not by dropping out — but by plunging in — into the maelstrom of life itself — that thou shalt find thy wisdom! There be causes to espouse!! There be battles to be won! … Yea, thou mayest drop out fore’er — once Hela herself hath come for thee!” But the important plot point of that first part of the story sees a minor villain named Ulik freeing a monstrous evil force named Mangog from his ancient imprisonment, at which point Mangog sets out to destroy Asgard and bring about Ragnarok. We eventually learn that Mangog is an old enemy of Odin’s, a collective entity, the embodiment of an ancient dying race, with all the power of a billion billion beings. Now he wants only to bring about the end of all that is.

This story is probably the high point of Lee’s collaboration with Kirby on Thor. The dialogue and narration effectively sells Mangog as an unstoppable force, the inevitable death that must be fought though there’s no hope of victory. Odin has fallen into his Odinsleep, and cannot help as Mangog tears through Asgard’s defenses. Loki thinks only of using Mangog to destroy Thor, but his schemes collapse and he eventually realises his own destruction is coming. The depiction of the unstoppable progress of Mangog is perfectly paced; we see excellent foreshadowing when Thor, riding out to meet the monster, encounters the ruins he’s left behind. The battle between Thor and Mangog, taking up much of the third issue, is nothing short of spectacular, with well-timed cuts to advance sub-plots.

One of those sub-plots is the struggle of Thor’s friend, Balder, to escape the Queen of the Norns, Karnilla, who loves him despite her enmity to Asgard. Balder fights her minions, ensorcelled Asgardians, unyieldingly: “What matters life,” he asks, “if its price be the loss of pride, and honor?” His sheer bravery frees her pawns from her spell, leading them all to return to Asgard just in time for the final battle with Mangog: “Take arms, one and all!!” he cries joyfully. “We fight till we fall!”

One of those sub-plots is the struggle of Thor’s friend, Balder, to escape the Queen of the Norns, Karnilla, who loves him despite her enmity to Asgard. Balder fights her minions, ensorcelled Asgardians, unyieldingly: “What matters life,” he asks, “if its price be the loss of pride, and honor?” His sheer bravery frees her pawns from her spell, leading them all to return to Asgard just in time for the final battle with Mangog: “Take arms, one and all!!” he cries joyfully. “We fight till we fall!”

All Thor’s power cannot defeat Mangog. Inevitable doom draws closer. Mangog cannot be stopped, cannot be reasoned with. The characters all clearly believe they’re about to die, and all react accordingly. But, as Thor points out to a fleeing Loki, wherever Loki (or, by implication, anyone) goes, he will die when Ragnarok consumes all that is. Ultimately, of course, Ragnarok’s averted by the narrowest of margins. In a final battle with Mangog, Thor uses his power over storms to wake Odin, who defeats Mangog.

The story’s resolution feels rushed, and there are signs that Lee and Kirby weren’t quite on the same page in certain details. But it succeeds, and it succeeds because there’s a sense of unity to the structure of the whole thing. A story that begins with Thor waking Sif by the sound of his voice ends with him waking Odin by the power of his storm. The pacing of the four issues is excellent, and the sprawling battle scene between Mangog and Thor is a visual symphony of rising power. Fundamentally, the constant theme of the story is rejecting death, and throwing oneself into the struggle of life. Thor’s rejection of Hela, Balder’s rejection of Karnilla, Thor telling disaffected youth not to drop out — it all comes together in a story about how to meet death. It’s the flip side of Kirby’s favourite theme of evolution: the old order that must pass to give way to new.

The story’s resolution feels rushed, and there are signs that Lee and Kirby weren’t quite on the same page in certain details. But it succeeds, and it succeeds because there’s a sense of unity to the structure of the whole thing. A story that begins with Thor waking Sif by the sound of his voice ends with him waking Odin by the power of his storm. The pacing of the four issues is excellent, and the sprawling battle scene between Mangog and Thor is a visual symphony of rising power. Fundamentally, the constant theme of the story is rejecting death, and throwing oneself into the struggle of life. Thor’s rejection of Hela, Balder’s rejection of Karnilla, Thor telling disaffected youth not to drop out — it all comes together in a story about how to meet death. It’s the flip side of Kirby’s favourite theme of evolution: the old order that must pass to give way to new.

As it happens, the next major storyline reads like an inversion of the Mangog saga. When Thor falls prey to “warrior madness” — when, in defending Sif, he goes berserk — he’s punished for it. Punished, that is, for adopting the state of mind in which he will fight not for a cause, but for the sheer sake of fighting. It is oddly ironic that Odin, in myth the patron of berserkers, punishes his son for going berserk, but in the moment of reading, one doesn’t ponder such things. Thor must atone, decrees Odin, by seeking out the dread cosmic force called Galactus. Which Thor does, but instead of ending with a battle, Thor hears the story of how Galactus came to be; a reinforcement of the idea that struggle is not all there is. As it turns out, Galactus came from a race that was dying, like Mangog’s people; they’d been struck with a plague, and so determined on a cosmic suicide, sending a rocket to their sun to blow it up. Galactus, one of the astronauts on the rocket, was affected by the radiation, which played on the plague he was carrying. He evolved, and, after placing himself in a cosmic incubator, emerged as a terrible ravager of worlds.

The story unites the origins of the Fantastic Four and Superman, but again the point is that it’s a story of death and rebirth. As it happens, the foe Thor fought that brought on the warrior madness was another scientific attempt at creating more advanced, more evolved life, an artificial man who also had ‘incubated’ in a cocoon — a creature called Him (who, after his defeat by Thor, would go on to interesting things under the name Adam Warlock). Kirby’s stories by this point were sprawling one into another, his motifs recurring, his ideas contrasting and sparking and constantly growing.

The story unites the origins of the Fantastic Four and Superman, but again the point is that it’s a story of death and rebirth. As it happens, the foe Thor fought that brought on the warrior madness was another scientific attempt at creating more advanced, more evolved life, an artificial man who also had ‘incubated’ in a cocoon — a creature called Him (who, after his defeat by Thor, would go on to interesting things under the name Adam Warlock). Kirby’s stories by this point were sprawling one into another, his motifs recurring, his ideas contrasting and sparking and constantly growing.

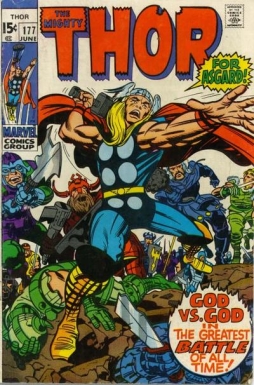

The last major storyline of the book reads like the conclusion of Kirby’s run at Marvel. It’s a sort of reprise of the Ragnarok theme of the Mangog story. When Odin again falls into his Odinsleep, Loki leads an army of evil into Asgard, usurps Odin’s throne, exiles the sleeping god to a far point of the cosmos, and unintentionally awakens the terrible fire giant Surtur — one of the characters whose advent first signaled the mythic themes that came to dominate the book. Thor leads the legions of Asgard in a desperate battle while Balder sacrifices himself to recover and revive Odin. It’s a strong story, but lacks the concentrated power of the Mangog apocalypse. Still, it’s an interesting note for Kirby to leave on: the end of the world, again.

I’ve spent nearly five-thousand words trying to explain what’s remarkable in Kirby’s Thor, yet I feel I haven’t scratched the surface. There are so many great moments (Thor fighting a column of Ego’s humanoids), characters (the Warriors Three: Errol Flynn, Clint Eastwood, and Falstaff teamed up as Norse gods by way of the Three Musketeers), and concepts (the giant Odinsword, whose unsheathing will bring on the end of the world). But what perhaps unites most of them is Kirby’s mythopoeic imagination, his ability to use existing myth and his ability to create new myths for a future he saw coming. Certainly, his themes were the themes of myth, life and death and the process of change. After Thor, he went on to create the ultimate super-hero series, the apotheosis of the super-hero, the super-hero as New God. But that began here, the working-out of those ideas present in the old gods of Asgard. I can’t say Thor was better than New Gods and the other Fourth World books, but I think it was no worse. It’s Kirby at the height of his powers, and there’s no greater thing that can be said of any super-hero comic.

I’ve spent nearly five-thousand words trying to explain what’s remarkable in Kirby’s Thor, yet I feel I haven’t scratched the surface. There are so many great moments (Thor fighting a column of Ego’s humanoids), characters (the Warriors Three: Errol Flynn, Clint Eastwood, and Falstaff teamed up as Norse gods by way of the Three Musketeers), and concepts (the giant Odinsword, whose unsheathing will bring on the end of the world). But what perhaps unites most of them is Kirby’s mythopoeic imagination, his ability to use existing myth and his ability to create new myths for a future he saw coming. Certainly, his themes were the themes of myth, life and death and the process of change. After Thor, he went on to create the ultimate super-hero series, the apotheosis of the super-hero, the super-hero as New God. But that began here, the working-out of those ideas present in the old gods of Asgard. I can’t say Thor was better than New Gods and the other Fourth World books, but I think it was no worse. It’s Kirby at the height of his powers, and there’s no greater thing that can be said of any super-hero comic.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

interesting post. I was never into superheroes as a kid and never read any comics.

I’ve recently started buying the marvel Essentials line. I’ve read the first 20 fantastic four issues, the first few Hulk, and the first Iron Man issue. I wasn’t sure if i wanted to read the thor line or not but this helps me make up my mind.

This reminds me that I should track down some Kirby Thor. And also read that giant Walt Simonson collection.

Great article! I used to read Kirby Thor as a kid. The grand battles were a sheer delight. I remember studying those images, spellbound by Kirby’s Asgard.

Matthew,

Fabulous article. Thor was one of my favorite comics as a kid, and this post brought it all back.

> I’ve recently started buying the marvel Essentials line… I wasn’t sure if i wanted

> to read the thor line or not but this helps me make up my mind.

Glenn,

Exercise a little caution (or a little patience) with the ESSENTIAL THOR. I purchased them years ago and plunged right in… and was very disappointed.

As Matthew mentions, the first eight issues were plotted by Stan Lee but scripted by his brother Larry Leiber, and then Robert Bernstein (writing as “R. Berns”) wrote the next seven. I found the first volume of THE ESSENTIAL THOR rather underwhelming, to say the least.

Things improve dramatically once Kirby starts drawing the series regularly, and Stan Lee become the regular scripter.

Thanks all for the good words!

Glenn, John’s right about the Essentials. Looking at my copies, I see that Volume 2 starts with #113, about when Kirby really began hitting his stride, so you might actually be better off starting there, then going back. Even the Tales of Asgard reprints are still doing done-in-one short stories at that point.

[…] Doctor Stephen Strange. Kirby’s Fantastic Four had publicly known identities from the start, and I’ve argued here previously that his run on Thor grew progressively less interested in Thor’s civilian identity of Don Blake, […]

[…] that I like a lot of adventure fiction quite a bit. I’ve written enough about Robert E. Howard, early Marvel comics, Jack Vance’s Dying Earth — I’ve even written about Fighting Fantasy gamebooks […]