Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Stephen King’s “On Writing”

I confess: I’m horror-illiterate. Being horrified on my way to some other reading experience is often worthwhile, but reading just to poke my amygdala with a stick is, for me, a joyless enterprise. Some horror writers are manifestly brilliant; I’m still not their audience. Chalk it up to an inherited predisposition to PTSD.

I confess: I’m horror-illiterate. Being horrified on my way to some other reading experience is often worthwhile, but reading just to poke my amygdala with a stick is, for me, a joyless enterprise. Some horror writers are manifestly brilliant; I’m still not their audience. Chalk it up to an inherited predisposition to PTSD.

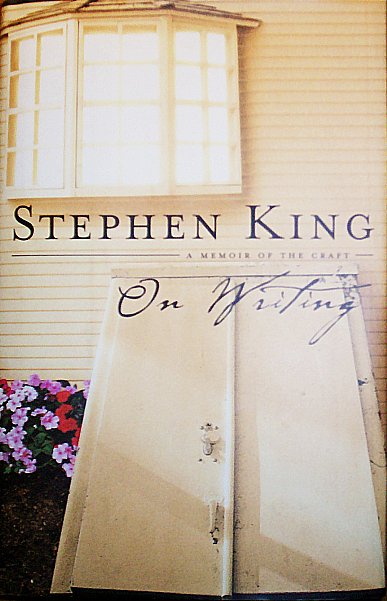

And yet Stephen King’s On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft is one of my favorite writing books. It’s unusual among writing books for its combination of memoir and manual. The memoir could have stood on its own; the manual could not. King knows that most of the true and useful things that can be said in a book to a beginning writer have been said many times, so he finds a way to say those things in a context that spins together cautionary tales, zany vignettes, and roaring triumphs. When he talks about what a writer needs in the way of work space, he shows us the corner of an attic where he wrote his first stories as a child, the laundry room in a trailer where he wrote his first novels, the uselessly enormous and overcompensating desk he bought during the early coke-snorting days of his wealth, and the study-turned-family-room where his kids lounge on couches while he writes contentedly in a corner. There’s something practical, and something human, to be learned from each of those workspaces.

The book is structured in four main movements: two central sections of advice on craftsmanship, bracketed by two sections about the writing life in general by way of King’s own writing life. The opening movement is cheekily titled “C.V.” A C.V., or curriculum vitae, is what an academic has instead of a resume. For a writer who has been so many times disdained by academics to appropriate the term, and then interpret the Latin curriculum vitae literally as the course of his life, is gutsy.

For King in particular to caption his early life–constantly uprooted, fatherless, poor, chaotic, addicted–with an abbreviation that signifies order and prestige, well, that’s potent irony. He has lived the kind of life that mainstream literary fiction writers are supposed to reveal on the page in all their gritty quotidian hopelessness, except that King’s love of escapist stories allowed him actually to escape.

And once he had escaped the hopeless grind of his working poor childhood, he had to escape the substance abuse that began in his teens and poisoned long stretches of his fame and success. It’s one thing to tell young writers that they don’t need alcohol to write. It’s another thing to bring them on a guided tour of one’s own personal catastrophes and then out into a new phase of creative freedom and joy that’s only possible when the addictions are beaten.

Most young writers are starving for role models. The adults in their lives are more likely to try to save them from their ambitions (You’ll starve! Don’t quit your day job!) than to offer any useful support. The writing lives kids learn about in their teens tend to be the sensationalistic wrecks, the writers lost to depression, addiction, compulsion. King argues passionately that a writer can have an authentic creative process, professional success, and a sane, happy family life all at the same time. On behalf of the Plath-addled teenager I was and the baffled students I teach, I want to give the man a medal for service to all writerkind.

The “Toolbox” section of the book makes a case for building a thorough foundation in basic language skills. Do not underestimate the need of the under-prepared teenage would-be writer to hear such a case made. Here we come to my one quibble with the book. Oh, I feel like such a pedant saying it, but it pained me, physically, right here, every time King refers to the passive voice as the “passive tense.” I map out the five dimensions of the English verb system for my students just about every week, and it’s not that hard to get this stuff right. I try to remind myself that King got hit by a van and nearly died of his injuries about midway through the process of writing this book, and if calling the passive voice a tense is the biggest glitch that got past him while he was fighting for his life, that’s forgivable. I hope somebody fixes it in a future printing, though. (Hey, publisher folks, it’s just one word, occurring maybe half a dozen times, but it throws a disproportionately large shadow on the credibility of the whole book. Whatever it costs to make that minor change, it would be worth it.)

The “Toolbox” section of the book makes a case for building a thorough foundation in basic language skills. Do not underestimate the need of the under-prepared teenage would-be writer to hear such a case made. Here we come to my one quibble with the book. Oh, I feel like such a pedant saying it, but it pained me, physically, right here, every time King refers to the passive voice as the “passive tense.” I map out the five dimensions of the English verb system for my students just about every week, and it’s not that hard to get this stuff right. I try to remind myself that King got hit by a van and nearly died of his injuries about midway through the process of writing this book, and if calling the passive voice a tense is the biggest glitch that got past him while he was fighting for his life, that’s forgivable. I hope somebody fixes it in a future printing, though. (Hey, publisher folks, it’s just one word, occurring maybe half a dozen times, but it throws a disproportionately large shadow on the credibility of the whole book. Whatever it costs to make that minor change, it would be worth it.)

What’s marvelous in the section of On Writing called “On Writing” is King’s account of the relationship between the writer’s conscious mind and the writer’s unconscious mind. He has, many times, spoken and written about what he calls “the guys in the basement,” the internal others whom he experiences as doing much of the creative work while he’s not looking. This isn’t the only way to write, or necessarily the best or most successful for everyone, but it’s pretty similar to mine, so I’m glad to have a common reference point with other writers when conversation turns to process. (Actually, my process is more like Robert Louis Stevenson’s than like Stephen King’s, but more people have heard about King’s guys in the basement than about Stevenson’s dream helpers.)

What’s marvelous in the section of On Writing called “On Writing” is King’s account of the relationship between the writer’s conscious mind and the writer’s unconscious mind. He has, many times, spoken and written about what he calls “the guys in the basement,” the internal others whom he experiences as doing much of the creative work while he’s not looking. This isn’t the only way to write, or necessarily the best or most successful for everyone, but it’s pretty similar to mine, so I’m glad to have a common reference point with other writers when conversation turns to process. (Actually, my process is more like Robert Louis Stevenson’s than like Stephen King’s, but more people have heard about King’s guys in the basement than about Stevenson’s dream helpers.)

The part of the book I could never put down, either of the times I’ve read it, is the blandly titled “On Living: A Postscript.” Oh, come on, what kind of title is that? It should have been called something like, “How Some Drunk Guy Driving while Wrestling a Rottweiler Named Bullet Broke Most of My Bones, but Still Couldn’t Stop Me from Having an Awesome Writing Life with my Loving Family, So There!” I’ve had a few setbacks and disruptions to my creative process, but so far none of them have necessitated a medevac helicopter. I found this section immensely heartening, and I think any writer who faces a change in life circumstance that demands adjustments to her creative process might find it so, too. Would the young writer who needs the “Toolbox” section find that “On Living” spoke to him? I don’t know, but the memory of having read it in youth might speak to him decades later when he needed it. Were we to map this Memoir of the Craft onto Aristotle’s plot diagram–the spiky one we all had to learn in high school–“On Living” would be the climax, after which comes the denouement.

A further postscript, “And Furthermore: Door Shut, Door Open,” includes a few pages of King’s first draft of the short story “1408,” with all his handwritten markup showing how he meant to change it for the second draft. Surrounding those marked up pages are explanations of his revision process, and a few bon mots about revision generally. A list of books King admires rounds out the volume, and off we go to the library, because writing requires reading.

Speaking of reading, what are your favorite Stephen King novels and stories? What can a person who rarely finds satisfaction in the horror genre enjoy that still gives a sense of King at his own fictional best?

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

Hmm … a bit tough since you don’t like horror … 😉

It’s been along while since I read it, but ‘Salem’s Lot is one of the most intesively scary books I have ever read. Same thing for It, alhouh I hated the ending.

And The Stand is also a really great read, IMO.

In all of the above cases, absolutely forget the movies of the smae name. None of them even come close to the written versions.

Eyes of the Dragon is excellent and it’s much more of a YA fantasy novel than horror. (Although, being King, there are some gross bits.)

There’s also the Gunslinger series — the first book is a bit odd and I don’t think the ending was entirely successful, but books 2-4 in particular are probably my favorite things he’s written.

Also track down a copy of Different Seasons and read The Body (the longish short story on which Stand By Me was based).

Having thought about it more, you should give The Stand a try, as it’s not really horror. Some minor scary bits and quite a bit of tension, but nothing like some of the others.

“On Writing” is actually my favorite piece of Mr. King’s writing. Though I do admit that the original story “The Gunslinger,” read in an anthology at age 13, left quite an impression. I’m not a horror fan, and Mr. King’s endings at times leave me wanting, but credit where credit is due. The man can write

http://about.me/ken_lizzi

There’s always “Different Seasons” The anthology that eventually became the movies Apt Pupil, Stand by Me, and The Shawshank Redemption.

I will also agree that “On Writing,” especially the part about his accident, makes for a very unique memoir of the writing life.

On Writing is the only thing of his I’ve read, and I think it’s brilliant. What was that about wishing he could remember writing Cujo because it’s a pretty good book?

And now for something completely different, my second favorite memoir of a writer is Patrick F McManus’s How I Got This Way. It’s yet another collection of humorous stories, but the open and closing chapters are nonfiction; the former about his childhood and the latter about how he became a writer. Hugely entertaining and containing some good bits of wisdom.

And for those of you playing name-drop bingo, yes, that was King and McManus in the same post. You’re welcome.

Jeff, he couldn’t remember writing Cujo because he wrote it while saturated with alcohol and cocaine. Looking back, he wishes he could recall the fun parts of the writing process.

McManus is new to me. I’ll have to take a look at How I Got This Way.

Thank you all for your suggestions! Looks like The Stand and Different Seasons are the places to start.

Sarah, be warned that McManus writes humor, most of which has been published in magazines like Field & Stream. There’s nothing speculative about his writing (other than physics is often defied). He’s had me laughing until I cried on many an occasion.

Hey there Sarah, sorry I’m late to this gathering.

I liked everything about On Writing except King, one of the most hardcore ‘seat-of-the-pantsers” I’ve encountered, basically suggesting would-be authors ought to do it his way.

I read with something close to astonishment of how he wrote with no outline, with no idea where his tale might go, but liked it that way because he believes that in some fashion his stories already exist, and that in writing he is digging them out intact from some undefined metaphysical strata. He sees himself like some archeologist of fiction, comparing his writing to excavating buried dinosaur bones. He just follows the ‘bones’ down, and doesn’t worry, because “all stories come out somewhere”.

This strikes me as absolutely fabulous advice to follow if you are Stephen King, but terribly suspect if you happen to be anyone else.

I could easily see myself following the bones of my unfolding story down into the earth interminably, producing less a skeleton than a collection of misshapen bones that never fit together at all.

I could see my story never “coming out” anywhere, but puttering off into vague, inconclusive and unsatisfying dead ends.

I’m glad it works for him, but I could never write like that.

With that off my chest, The Stand is very long, quite diffuse, and laden with a degree of soft, even sentimental, spirituality, all of which keep it from being one of my favorites by the author. I enjoyed it well enough, and many King fans list it as their favorite, but it doesn’t seem to me to be a good introduction to the author’s work.

To my mind The Shining is maybe King’s best book, and a contender for the best haunted house novel. There are a number of ethereally chilling scenes with no carnage, with not even the threat of violence, but instead a disturbing sense of ordinary people coming into contact with the otherworldy. There’s some gross stuff too, of course, but here King also shows the kind of delicate touch that isn’t seen often enough in modern horror fiction.

[…] Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Stephen King’s On Writing […]