Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars, Part 11: John Carter of Mars

So it ends here, not with a climatic epic, but with a bit of house cleaning almost fifteen years after the author’s death. The final book in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s career-spanning Barsoom saga is a slender volume containing two unrelated novellas.

So it ends here, not with a climatic epic, but with a bit of house cleaning almost fifteen years after the author’s death. The final book in Edgar Rice Burroughs’s career-spanning Barsoom saga is a slender volume containing two unrelated novellas.

I’ve called this review series “Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Mars,” but that title is a smidgeon deceiving when discussing the two stories here. One doesn’t take place on Mars, and the other was not written by Edgar Rice Burroughs. My apologies going forward.

Our Saga: The adventures of Earthman John Carter, his progeny, and sundry other natives and visitors, on the planet Mars, known to its inhabitants as Barsoom. A dry and slowly dying world, Barsoom contains four different human civilizations, one non-human one, a scattering of science among swashbuckling, and a plethora of religions, mystery cities, and strange beasts. The series spans 1912 to 1964 with nine novels, one volume of linked novellas, and two unrelated novellas.

Today’s Installment: John Carter of Mars (1964)

Previous Installments: A Princess of Mars (1912), The Gods of Mars (1913), The Warlord of Mars (1913–14), Thuvia, Maid of Mars (1916), The Chessmen of Mars (1922), The Master Mind of Mars (1927), A Fighting Man of Mars (1930), Swords of Mars (1934–35), Synthetic Men of Mars (1938), Llana of Gathol (1941)

The Backstory

Edgar Rice Burroughs died in 1950, two years after the publication of Llana of Gathol. Two novellas from the Mars series remained orphaned, having only appeared in magazines: “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” and “John Carter and the Giant of Mars.” It wasn’t until 1964 that Canaveral Press published them together under the deceivingly archetypal title John Carter of Mars.

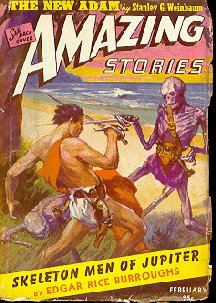

The tale behind “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” is simple enough. After success selling the four novellas that made up Llana of Gathol, Burroughs started another quartet. He wrote the first installment in October–November of 1941. Because of the U.S. entrance into World War II and Burroughs’s work as a correspondent, he never wrote the other three parts. After failing to sell “Skeleton Men” to Blue Book, Burroughs set it up at Amazing Stories for the February 1943 issue.

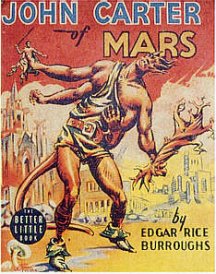

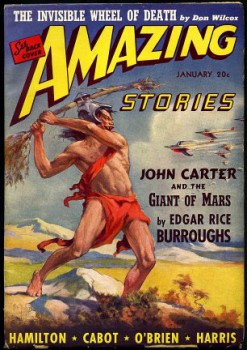

“John Carter and the Giant of Mars” is an entirely different matter. Whitman Publishing approached ERB to write a John Carter story for their “Better Little Books,” a children’s series of books with alternating pages of illustration and text. Burroughs agreed (he had already written some Tarzan stories for the series), and assigned his son, John “Jack” Coleman Burroughs, to handle the illustrations. An expanded version of this story appeared in the January 1941 issue of Amazing Stories, where it immediately sparked a reader outcry of “fake!” (If the Internet existed then, the storm on forums and blogs would have been a Level 5 tornado.) Fans of Burroughs thought the style was wrong, sounding nothing like their beloved author. That it was written in third person from John Carter’s point of view, something never seen before, furthered suspicions. In Amazing’s letter column, the editor reassured his readership that this was exactly the manuscript as received from Edgar Rice Burroughs, and no one at the magazine had tampered with it.

“John Carter and the Giant of Mars” is an entirely different matter. Whitman Publishing approached ERB to write a John Carter story for their “Better Little Books,” a children’s series of books with alternating pages of illustration and text. Burroughs agreed (he had already written some Tarzan stories for the series), and assigned his son, John “Jack” Coleman Burroughs, to handle the illustrations. An expanded version of this story appeared in the January 1941 issue of Amazing Stories, where it immediately sparked a reader outcry of “fake!” (If the Internet existed then, the storm on forums and blogs would have been a Level 5 tornado.) Fans of Burroughs thought the style was wrong, sounding nothing like their beloved author. That it was written in third person from John Carter’s point of view, something never seen before, furthered suspicions. In Amazing’s letter column, the editor reassured his readership that this was exactly the manuscript as received from Edgar Rice Burroughs, and no one at the magazine had tampered with it.

It turns out, however, that the fan outcry was justified. In 1964, Burroughs’s son Hulbert revealed the truth: ERB had only a minor role in crafting the story, which was otherwise the work of Jack Burroughs. The special requirements of a Whitman Better Little Book — an illustratable scene on every page — made the author uncomfortable, so it was natural for the artist to write the story instead. Although “John Carter and the Giant of Mars” still has the name Edgar Rice Burroughs on it, it is almost entirely the work of his son. The version printed in Amazing and subsequently in Canaveral’s John Carter of Mars is 5,000 words longer than the 15,000-word Whitman Book version.

The Story

The two stories have no connection to each other, and no framing device tries to pretend that they are anything other than separate entities.

John Carter and the Giant of Mars: A mysterious figure named Pew Mogel kidnaps Dejah Thoris and offers to release her in exchange for control over Helium’s iron works. John Carter tracks Pew Mogel to the abandoned city of Korvas, where he finds that Pew Mogel is a synthetic creation of Ras Thavas (the titular Master Mind of Mars) with a legion of various Barsoomian beasties under his command. He also built his own synthetic creation: Joog, a hundred and thirty-foot giant. (He had a free afternoon, I guess.) Pew Mogel plots to destroy Helium with his armies, and only John Carter and a pack of Martian rats attached to parachutes can stop him! No, really.

The Skeleton Men of Jupiter: The ruling race of Jupiter (“Sasoom” in the language of Mars), the skeletal Morgors, plot an invasion of the Red Planet with Helium as their first target. Using a soldier of the Martian city of Kor named U Dan as their tool, the Morgors lure John Carter into a trap and whisk him to Jupiter on a spaceship. To further convince him to aid them in their invasion, they also kidnap Dejah Thoris. John Carter allies himself with the Savator, the oppressed race of Jupiter, and a rebel Morgor, Vorion, to save his love. Carnivorous plants and fights in an arena are involved.

The Positives

The Positives

I have little to say about “John Carter and the Giant of Mars” since it isn’t an Edgar Rice Burroughs story except that he gave it his approval and may have suggested parts of the plot. It’s an adequate adventure yarn viewed through the lens of a younger reader, with waves of strange beasts and constant action. It seems like every creature of Barsoom makes an appearance: malagors, white apes, ulsios. Some of the concepts, like Pew Mogel building the giant from the bodies of red Martians, might have worked well in an actual Edgar Rice Burroughs story. It also brings back a few classic characters from the original trilogy, such as Tars Tarkas and Kantos Kan, although not terribly well.

But “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” is strong. Surprisingly strong, considering this point in Burroughs’s career was one of his weakest. It’s far superior to Synthetic Men of Mars or any of the parts of Llana of Gathol. Getting off Mars and onto a different world seems to have restarted Burroughs’s creative reactor. Going to Venus in the Amtor novels wasn’t so successful, but having John Carter as the hero gave ERB the boost he needed to get the most out of the short time on Jupiter. It’s a hellish volcano world under thick purple skies and feels more otherworldly than anything on Venus — actually, it feels more like the real Venus with its volcanic surface and choking cloud cover.

The story is better in the second half, after it dispenses with rescuing Dejah Thoris and U Dan’s mate, Vaja. John Carter gathers his own crew of Savators, who escape after an exciting arena fight (yeah, it’s been a stretch since ERB managed a good one) and then try to make it to their respective homes. For the short time they appear in the story, Carter’s two Savator allies, Phor Lar and Han Du, make good impressions. Phor Lar transitioning from a hateful braggart to a loyal companion is better characterization than anything seen in the last two Mars books. Han Du eventually leads Carter to the story’s most interesting SF concept: a city invisible from the outside, with the inhabitants having to memorize locations — like their own homes — based on the natural visible terrain.

Perhaps “John Carter and the Giant of Mars” provides a bonus, since its inclusion next to a genuine piece of ERB’s writing enhances the author’s style. “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” isn’t classic Burroughs, but it feels vibrant and florid beside the flat children’s style of “Giant of Mars.” Coming at the very end of Barsoom, it reminds us of what made ERB such a memorable writer.

The Negatives

What is there really to say about “John Carter and the Giant of Mars?” It’s not very good, but that isn’t the fault of the person who didn’t write it. I’ve never read the Whitman Better Little Book version with Jack Burroughs’s illustrations, but it must go down better in shorter form targeted at younger readers. The endless action exists to provide fodder for an illustration every few paragraphs, and the resulting pile-up feels like a kid with short attention span telling the plot of movie with all the connective drama taken out. The writing style is distractingly nothing like ERB, lacking his florid arabesques; anyone familiar with Barsoom will find the misuse of terms a dead giveaway that another writer is at the helm. Everything simply feels “off.” Casual readers can skip this; only those with an interest in the complete publishing history of Barsoom need apply.

The biggest flaw with “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” is that it concludes long before the new planet gets properly exploited. John Carter ends the story still on Jupiter, with no indication about how he’ll get back to Mars. Although the novella contains a complete story arc, it still is supposed to lead into three more installments. It can’t help but feel incomplete, with Jupiter just getting warmed up for more adventuring. If ERB had a full novel to work out this setting, he might have paced events differently instead of trying to get the action moving as fast as possible — there’s plenty to explore here, but not enough time to dwell on the most interesting parts. The invisible city is a good example: it’s a wild idea, but it does nothing in the actual story except show up for a few pages. The younger ERB could have easily worked the premise for a few chapters of action or suspense; now the ideas are tossed out fast and abandoned.

The biggest flaw with “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” is that it concludes long before the new planet gets properly exploited. John Carter ends the story still on Jupiter, with no indication about how he’ll get back to Mars. Although the novella contains a complete story arc, it still is supposed to lead into three more installments. It can’t help but feel incomplete, with Jupiter just getting warmed up for more adventuring. If ERB had a full novel to work out this setting, he might have paced events differently instead of trying to get the action moving as fast as possible — there’s plenty to explore here, but not enough time to dwell on the most interesting parts. The invisible city is a good example: it’s a wild idea, but it does nothing in the actual story except show up for a few pages. The younger ERB could have easily worked the premise for a few chapters of action or suspense; now the ideas are tossed out fast and abandoned.

Of course, there’s also the realization that … there’s no more after this. I found I was reluctant to finish reading “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter” and had to force myself to pick it back up each time I put it down after a chapter or two. It wasn’t because it bored me. It was because when I finished it, that was the end of it all. A year spent moving through Burroughs’s career via Barsoom, and this short story was the final curtain. And it’s such an ordinary conclusion, even if it improves over the last few books. Barsoom deserved to finish with something similar to the triumph of The Warlord of Mars.

John Carter rails against scientists throughout “Skeleton Men” in order to make the impossible setting on Jupiter seem like it might happen. The difference in planetary science between 1912 and 1941 was gargantuan, so ERB needed to jump through a few flaming hoops to get this to make sense. But Carter’s petty rants are, well, petty. They end up drawing attention to how bizarre the science is. (Even though Jupiter should exert crushing gravity on humanoids, the lighter gravity is explained away as the “centrifugal force [of Jupiter’s rapid rotation] … more than outweigh[ing] the increased force of gravitation.”) Burroughs already earned readers’ trust and acceptance with his fuzzy science, and should have just told his story without having to apologize — or threaten.

Once again, Dejah Thoris gets kidnapped. An accidental looping back to the beginning of the Martian novels, but still a “here we go again” moment. The story picks up noticeably after her rescue at the midpoint, when the plot then changes into a “team survival” story.

Why is John Carter so surprised to see intelligent carnivorous plants on Jupiter? Did he forget about his battles with hordes of plant men on Mars? And why is Carter, who has only made brief temporal visits to Earth since the 1870s, aware of pop culture items such as the song “Rose Colored Glasses”?

Why is John Carter so surprised to see intelligent carnivorous plants on Jupiter? Did he forget about his battles with hordes of plant men on Mars? And why is Carter, who has only made brief temporal visits to Earth since the 1870s, aware of pop culture items such as the song “Rose Colored Glasses”?

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: “The city was quite as depressing in appearance as is Salt Lake City from the air on an overcast February day.”

Best Moment of Heroic Arrogance: This stunning bit of poor self-awareness from John Carter: “…it is a failing of fighting men to boast of their prowess. Not of all fighting men, but of many, usually those with the least to boast of.”

Times a “Princess” (Female Lead) Gets Kidnapped: 2

Best Creature: The carnivorous plants of Jupiter.

Most Imaginative Idea: The one-way invisible walls of Han Du’s city.

Take That, Science! “In the adventure I am about to narrate, fact and theory will again cross swords. I hate to do this to my long-suffering scientific friends; but if they would only consult me first rather than dogmatically postulating theories which do not meet with popular acclaim, they would save themselves much embarrassment.”

Should ERB Have Continued the Series? Yes, actually. Not only do I wish he finished the three novellas after “Skeleton Men,” I think he might have written something interesting about Barsoom in the years after the war, when he experienced a short creative surge.

Next: I’m going to keep doing Burroughs reviews in 2013, turning to some of the books outside of his main series. So, let’s see … The Mucker.

Series Wrap-Up

The Martian novels of Edgar Rice Burroughs form a cornerstone of modern science fiction, even if they haven’t gained the level of pop-culture dominance of some later science-fiction properties. It’s unfortunate that the excellent movie bid to expand Barsoom’s visibility, this year’s John Carter of Mars from director Andrew Stanton, was publicly hyped as a box-office disaster after Disney bungled the marketing. Nonetheless, Barsoom’s legacy is solid: it both opened up the genre to space opera and hard science fiction. The latter claim may seem outlandish, but reading through all the books this year made me aware that Burroughs was attempting to root his fantastic story elements in the framework of what people knew about Mars in the early twentieth century. Especially in the initial “John Carter Trilogy,” Burroughs sets his cultures and creatures in a Martian possibility instead of the early planetary stories of pure whimsy, where other worlds were simply made into fantasy-land versions of Earth. We would never have gotten Stanley G. Weinbaum’s realistic alien creatures if Burroughs hadn’t explored the territory first.

Taken on their own, removed from their cultural pedestal, the Martian books are Burroughs’s most consistent series for quality. Some of the Tarzan novels can match the best individual installments of Barsoom, but the ape man’s overlong saga lingered far past its expiration date. It isn’t until Synthetic Men of Mars — the third-to-last volume — that the Mars novels plunge in quality.

Taken on their own, removed from their cultural pedestal, the Martian books are Burroughs’s most consistent series for quality. Some of the Tarzan novels can match the best individual installments of Barsoom, but the ape man’s overlong saga lingered far past its expiration date. It isn’t until Synthetic Men of Mars — the third-to-last volume — that the Mars novels plunge in quality.

The original trilogy (A Princess of Mars, The Gods of Mars, and The Warlord of Mars) is one of the glittering achievements of the early pulps, bursting with wonder and excitement. The Gods of Mars, as I anticipated back when I reviewed it, is the greatest book of the series, and among the five or so finest in the ERB canon. It should not be read in isolation, however: the trilogy works as a tight unit, even if Burroughs hadn’t mapped it out fully at the beginning as one. It’s during this trilogy that Mars comes across best as a unified setting. Later books expanded the planet and came up with ingenious ideas (jetan and the city of Lothar foremost among them) but tended to abandon established Martian fauna and some of the best characters. It surprised me upon re-reading the books how much the green Martians disappear after Thuvia, Maid of Mars, cropping up only as occasional walk-ons, and that fantastic characters such as Tars Tarkas and delightful Woola hardly turn up again.

I can understand the casual readers wanting to stop after finishing the John Carter Trilogy, but it’s worth hanging around to get to A Fighting Man of Mars, which is exceptional for something so deep into a series. I might advise skipping The Master Mind of Mars, but it’s short enough that it isn’t a serious obstacle.

Unlike the Tarzan novels, Mars doesn’t need its original hero, John Carter, to succeed. In fact, Carter’s return to the lead (Swords of Mars) after a long absence ended up a mistake on Burroughs’s part. Carter’s story was over, and ERB was never able to make him as interesting again as in that first trilogy. Fortunately, Barsoom is too wild and weird a place to depend on one Earthman, and the vivid setting kept the fuel in the tank. Thuvia, Maid of Mars and The Chessmen of Mars worked with the shift to third-person because of the astonishing imagination invested in both, while A Fighting Man of Mars discovered a new first-person hero who worked as a counterpoint to John Carter’s near-invincibility. I wouldn’t have minded another book or two with Tan Hadron as the lead.

Of course, the Martian books suffer from the usual flaws of Burroughs as a storyteller: continual quests for kidnapped princesses, crash-landings that always place the heroes near a bizarre lost city, and strained romances based on the most contrived of obstacles. But there is so much quality in the Mars tales that none of these overwhelm the enjoyment until the end of the series.

In the rankings below I’ve included all the books, with the stories of Llana of Gathol collected under the overall title, plus “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter,” but excluded “John Carter and the Giant of Mars.”

Series Ranking, from Best to Worst

- The Gods of Mars

- A Fighting Man of Mars

- The Warlord of Mars / Thuvia, Maid of Mars

- The Chessmen of Mars

- A Princess of Mars

- Swords of Mars

- The Master Mind of Mars

- “The Skeleton Men of Jupiter”

- Llana of Gathol

- Synthetic Men of Mars

I would like to acknowledge John Flint Roy’s A Guide to Barsoom (1976) and Richard A. Lupoff’s Edgar Rice Burroughs: Master of Adventure (1965) for aiding in the research for these articles.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

Yes, yes Michael Whelan does just goddamn rule.

At the risk of repeating myself, I’ve really enjoyed this series.

For me the biggest problem with Giant of Mars is that it can hardly go for a single page without just outright breaking Barsoomian canon — they’re flying “planes” and firing “ray guns” and at one point someone is carrying a sub-machine gun.

And yes, it’s too bad that he never completed Skeleton Men of Jupiter. (Or, for that matter, wrote any other books in the setting of Beyond the Farthest Star.)

One Barsoom canon item that “Giant of Mars” continually breaks is using the term “Martian rats.” ERB always calls them “ulsios,” dammit! He may mention they are “a kind of Martian rat,” but that’s it. That drove me crazy. It seems nitpicky, but after spending a year with Burroughs’s style, these deviations really stick out.

Argh! Good point re: the rats.

Although, especially when I see the full spread, that may be my favorite Whelan Barsoom cover. (But what’s the source of the Mars in Full illustration?)

Unfortunately, the source is “John Carter and the Giant of Mars.” It’s JC and Dejah Thoris escaping on the malagors.

My favorite Whelan is still The Gods of Mars followed by Thuvia, Maid of Mars.

Sorry — not the John Carter cover, but the one just above with the green men and white ape and banth and such.

[…] Black Gate’s excellent essayist Ryan Harvey (really, why doesn’t this guy have a paying gig doing this kind of thing?) read every single Burroughs Mars book over the course of the last year, detailing highs, lows, weirdest moments and generally providing the kind of overview that I have always wanted. Me, I’ve read and enjoyed a little over half of the eleven books, and thanks to Harvey’s reviews I now have a pretty good idea about which ones I will probably skip. Harvey’s talented, honest, and funny, and any fan of the Mars Burroughs stuff –or anyone curious about the series- should visit these, pronto. Here, Part 11 links to all of the preceding sections. […]

[…] Mars” review series will continue all the way until the last book (called, appropriately, John Carter of Mars). I’ll have a few more surprises to celebrate the centennial of A Princess of Mars and Tarzan of […]

[…] Edgar Rice Burroughs’ Mars, Part 11: John Carter of Mars […]

[…] (Black Gate): “Compared to Burroughs’s other two long-running science-fiction series, Mars/Barsoom and Venus/Amtor, Pellucidar is more difficult to summarize. The Venus novels were written over a […]