Teaching and Fantasy Literature: More on Writing, and Teaching, on Your Feet

To my surprise, I got a bunch of emails asking for more details about the weird teaching gig I described in last week’s post. How exactly did it work, teaching creative writing while kicking a soccer ball around my student’s basement?

To my surprise, I got a bunch of emails asking for more details about the weird teaching gig I described in last week’s post. How exactly did it work, teaching creative writing while kicking a soccer ball around my student’s basement?

This student was so blocked about writing in most areas of his life that, unless I was right there with him, he rarely wrote anything on his project–as much as he loved it. The first thing we did when we got to our work space was run around kicking the ball back and forth for five minutes or so while he talked his way through what he wanted the next scene to do. As soon as he reached the point where he had some proto-sentences in mind and a paragraph’s worth of ideas about how he wanted to string them together, I’d say, “Okay, now write that down, quick!” We were trying to catch the thought before it got lost. He’d tinker while he got the words on the paper, and sometimes take out his hard copy of the manuscript so far and check details or make small changes to integrate the new material. I pressed him to keep at the pen-on-paper step for a minimum of five minutes; sometimes he wanted to go on far longer than that when he was on a roll. When he ran out of steam for his longhand work, we were up and running again.

In some ways, it was not so different from the office hours I held when I taught freshman composition at a big state university. I learned early in the freshman composition gig not to let the anxious or reluctant writer leave my sight before s/he put some words on paper, or else by the time s/he got back to the dorms, all the ideas we had discussed would have evaporated. In content, though, the texts could not have been more different.

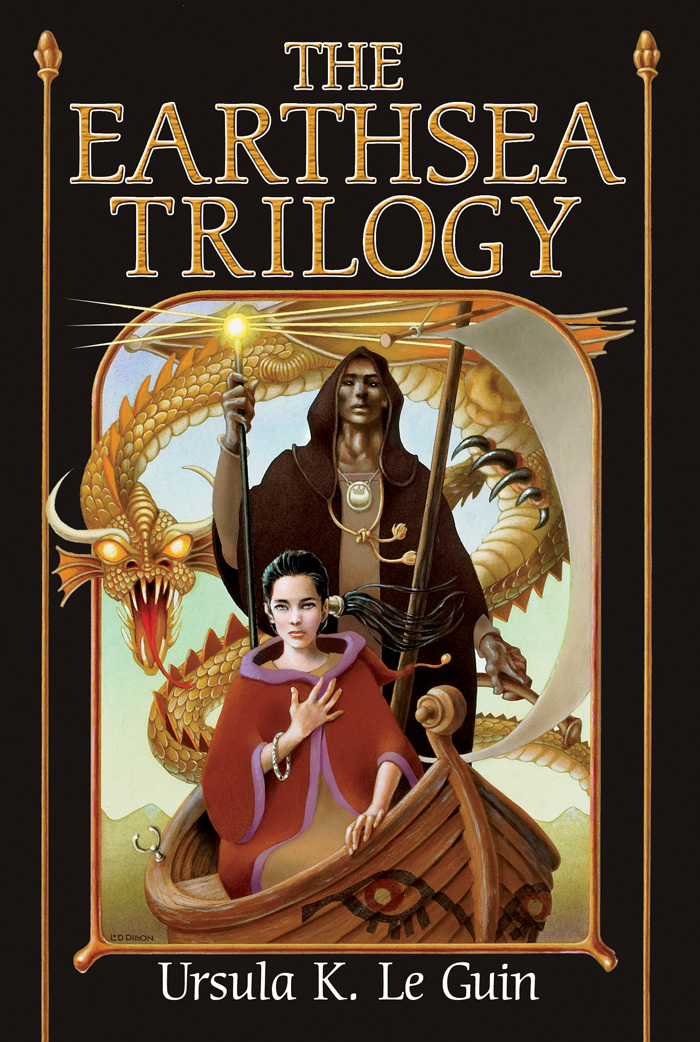

The soccer kid and I read Ursula Le Guin’s A Wizard of Earthsea together early on. He decided the story would have been much cooler if Ged had continued down the dark path of arrogance and folly.

Le Guin’s Ged fought dragons, and after that the worst thing he fought was himself. For a thirteen-year-old, or at least for this thirteen-year-old, the original Ged, with his hard-won wisdom and tempering of power with self-abnegation, was not nearly as exciting as a newly-imagined Ged who seized power when he saw it, and followed power’s lure to a final fiery doom.

So I got to have the bizarre experience of immersing myself in a story that totally demolished a classic of the genre and a personal favorite, that used the name of a beloved character to stand for exactly what the character struggled against through five books. My student’s Ged enslaved a dragon, conquered a world, drove the conquered to rebellion, and died in single combat with the man who might more typically have been the hero–but at least my student’s Ged took the hero down with him!

The soccer kid was a good boy. Such a good boy. His parents expected much of him. In nearly all ways, he rose to their expectations. He was not permitted a shadow self. Perhaps Le Guin’s Ged could embrace and integrate his shadow self because his teachers and peers all acknowledged that he had one. What fantasy recompense must a good boy offer his shadow self to keep it entirely in abeyance in his life?

I tried to be comfortable with the anti-hero my student developed, and usually I managed it. When I did not manage to feel comfortable, I tried to sound comfortable. And when I botched that, I had to come out and speak honestly about my discomfort as we kicked the ball back and forth. Dude, your protagonist is committing genocide in this scene. That’s especially confusing to me because your extended family lost people to genocide a couple of generations back. Be prepared for the possibility that your parents may have a strong reaction to this if you show them your manuscript. Ultimately, though, the anti-hero’s story was the one he wanted and needed to tell.

He told it in glorious technicolor, in dragonfire and blood, with a massive cast Cecil B. DeMille would have reveled in and Peter Jackson would have had to generate with CGI. He ended his tale on a battlefield strewn with the scorched dead, as the ragged remnants of a rebellion staggered forward to pull aside the wrecked wings of a fallen dragon, and found themselves suddenly free to rebuild their world–no dictator, no hero, no boss left to boss them. The story was a perfect product of a thirteen-year-old’s imagination. In that sense, Le Guin might well have preferred it over the two egregious attempts to adapt her book for large screens and small.

He told it in glorious technicolor, in dragonfire and blood, with a massive cast Cecil B. DeMille would have reveled in and Peter Jackson would have had to generate with CGI. He ended his tale on a battlefield strewn with the scorched dead, as the ragged remnants of a rebellion staggered forward to pull aside the wrecked wings of a fallen dragon, and found themselves suddenly free to rebuild their world–no dictator, no hero, no boss left to boss them. The story was a perfect product of a thirteen-year-old’s imagination. In that sense, Le Guin might well have preferred it over the two egregious attempts to adapt her book for large screens and small.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

[…] Teaching and Fantasy Literature: More on Writing, and Teaching, on Your Feet […]