The Golden Age of Science Fiction: The 1973 Locus Award for Best Short Fiction: “Basilisk,” by Harlan Ellison

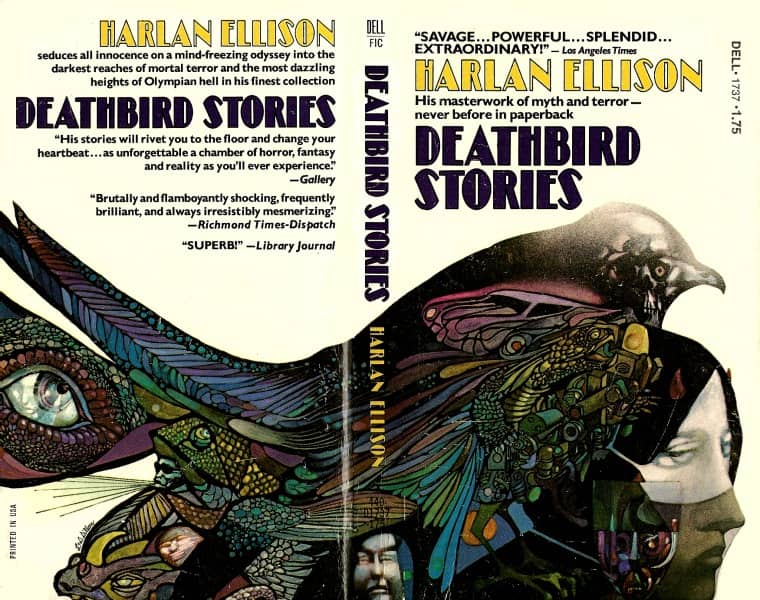

Deathbird Stories (Dell, 1976). Cover by Diane Dillon and Leo Dillon

In this time period the Locus Award for fiction went to novels, novellas, and short fiction, presumably both novelettes and short stories. (I’m not sure where the exact boundary between short fiction and novella was set.) Perhaps appropriately, the winner of the 1973 award, Harlan Ellison’s “Basilisk” is perhaps 7,000 words long, quite close to the current border between “short story” and “novelette” for both the Nebula and Hugo awards.

Harlan Ellison, who died in 2018, aged 84, was one of the most famous SF writers of my lifetime, and one of the most controversial. He also was one of the most celebrated, having won an astonishing 18 Locus awards, and been named SFWA Grand Master, as well as winning 8 Hugos and 2 Nebulas, and too many other awards for me to count.

Speaking personally, Ellison was one of those writers who, for the most part, I could admire without quite loving. A few of his stories were special to me – “On the Downhill Side” and “I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream” occur off the top of my head – stories as different from each other as one might imagine, but very effective. Much of the rest of his work struck me as impressive but overwrought, and often exchanging affect for effect, or choosing to impress instead of express. If you see what I mean. His technical skill, in the directions he chose, was astonishing, but the end results, at times, seemed a bit empty.

I met Ellison once, at Archon only a couple of years before his death. We shared a panel. He was quite frail by then, in a wheelchair. But once he got on “stage,” as it were, a switch flipped. He was fully ON, sharp, belligerent to great effect, funny, on point. I didn’t get to say a lot, but that was wholly correct, and not because he was bullying in any way, but because it was clear we all – on the panel and in the audience – wanted to hear what Harlan had to say. (We also had a conversation, a few years before, a totally unexpected phone call to me, concerning one of his late stories (a Nebula winner), and it was pleasant and completely professional.)

|

|

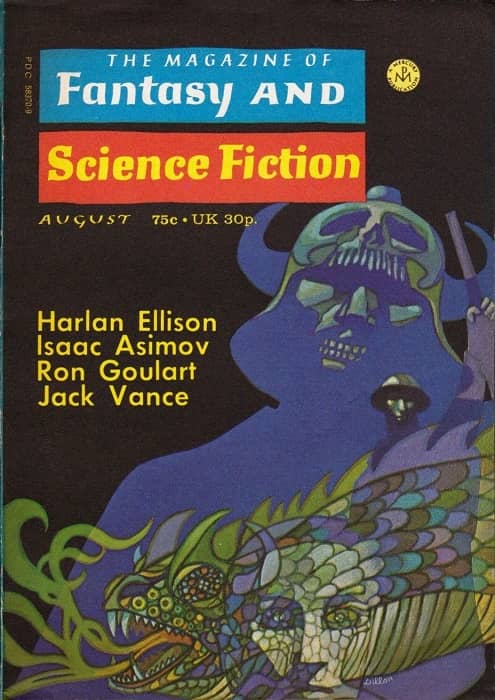

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1972. Cover by Diane Dillon and Leo Dillon

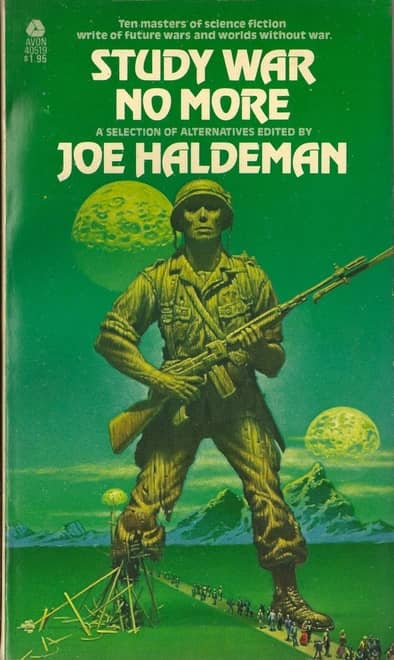

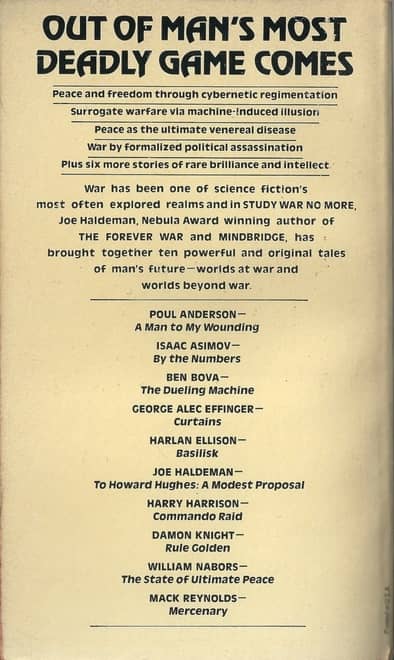

“Basilisk” first appeared in the August 1972 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and was reprinted in Ellison’s collection Deathbird Stories (1975) and Joe Haldeman’s anthology Study War No More (1977), among other places.

It concerns Vernon Lustig, an American soldier in an Asian war, presumably the Vietnam War, though it’s not specified. He is severely injured by an enemy boobytrap… and is captured and imprisoned and tortured. Sometime in that process he is possessed by some alien or otherwise unexplained creature called the Basilisk. And, presumably thanks to that creature, he destroys his captors in horrible ways. He is rescued, and returned to the US, but court-martialed, either for revealing secrets to the enemy, or for war crimes. But he’s acquitted. He returns to his Kansas home town, only to find himself a pariah, even to his ex-girlfriend, who has married a cartoon football player. Before long, he is confronted by the thuggish elements of his town, and takes terrible revenge.

|

|

Study War No More (Avon, 1978). Cover by Michael Whelan

It’s caricature throughout. I didn’t believe his Kansas hometown for an instant. I thought the portrayal of his (presumably) Vietnamese captors racist in the Deer Hunter sense. The ex-football player husband might have been believable if there was any sense he was created out of reality instead of out of cliché. I know Ellison was enraged at US involvement in the Vietnam War, but this sort of response is counterproductive. And, really, the fantasy element was both silly and unconvincing. (It should be noted that it was well-received at the time – not just this Locus Award, but Hugo and Nebula nominations too.)

Against all that there’s Ellison’s prose, which is truly impressive – his mastery of metaphor is impressive. His imagination is potent and original. His verbiage really works. But… but… it’s too much of a muchness. Each individual image is cool – but we don’t need ten in a row!

I think, in the end, that’s my main beef with Ellison – he didn’t know when to stop. I have a feeling he’d have said “Why should I stop?” And to that I can only answer, “Our tastes differ, sir!” I wouldn’t want SF without Ellison’s presence. It was a worthwhile influence. But – he’s not in my pantheon.

Rich Horton’s last review for us was “The Word for World is Forest,” by Ursula K. Le Guin. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. See all of Rich’s Black Gate articles here.

“He’s not in my pantheon.”

I think that sums up my feelings on Ellison nicely.

I certainly admire his talent, but that doesn’t mean I enjoy reading his fiction. He’s too much of a showman in his prose. (“Too much of a showoff,” is what I often think when I’m reading it.) By which I mean, Ellison’s stories often seem specifically structured to impress the reader with his ability, rather than successfully tell a story.

On the other hand, I found him a marvelous editor. I wish he’d done more anthologies. Like many others, I wish he’d finished LAST DANGEROUS VISIONS, for example. I suppose it’s uncharitable, but those weren’t intended to impress readers with Ellison’s prose, so I sometimes think they were lower priority for him.

Still argued about even after he’s gone. What would please him more?

Ellison really worked for me with several stories I’ve never been able to shake: “Croatoan,” “Pretty Maggie Moneyeyes,” and “A Boy and His Dog.” HIs imagination and use of language was spectacular.

Harlan and I were both Nebula short story finalists in 2003. Karen Joy Fowler won in our category. I have several Harlan stories from that weekend in Seattle, but everyone I know who met him has a story about the encounter.

I was going to write a paper about one of his short stories when I was in grad school. My advisor called him a bastard and insisted I choose someone else. I wrote the paper anyway for myself.

> I was going to write a paper about one of his short stories when I was in grad school. My advisor

> called him a bastard and insisted I choose someone else. I wrote the paper anyway for myself.

James,

That’s a great story. And it encapsulates just how controversial he is, even after his death.

I attended two World Cons (1973, ’74) and had the privilege of getting to hear Ellison read two of his stories to captive audiences: “Hitler Painted Roses” and “Adrift Off the Islets of Langerhans…” Those were the highlights of each of the cons. He also prefaced each story with personal experiences that were better than listening to stand-up comedy. Personally, he’s been one of my favorites ever since I read one of his stories in a “Best Of” anthology in 1966. Yes, he’s an acquired taste, but he left an indelible mark of the field, both as writer and as editor.

What can one say about Harlan that hasn’t already been said? Perhaps this: His best, most effective work—for my money—are his articles, columns, and essays. (See: The Glass Teat volumes I. & II.; An Edge in My Voice; divers editorial articles & digressions in various magazines.) Followed by his screenplays for television (especially: The Outer Limits, Star Trek). Then his work as an anthologist. (The Dangerous Visions series—the third volume bafflingly, inexcusably late: even the recent bio on his life—A Lit Fuse: The Provocative Life of Harlan Ellison; Segloff & Grubbs—sheds scant light on the issue; Harlan’s long-running excuse that he found it difficult to write appropriate introductions to each story a real head-scratcher.) Lastly (How he would howl!—threatening to beat me into red-sauced meatloaf forcibly divested of guttering, low candle-power sentience) I would place his earnest, ofttimes deeply disturbing, tough-guy-with-a-big-heart, hammer-to-the-head fiction.

This critical appraisal is not intended as diminishment: Harlan has written works that will forever remain in the sci-fi (How he would have waxed apoplectic over that acronym!) canon. As already mentioned, his literary awards are legion—and merited. It’s just that his most authentic voice—by turns wryly funny, hyper-logorrheic, darkly despairing, red-hot simmering rage’d [sic]—seem to me best showcased by his non-fiction writings.

Harlan was more than a writer: He was a performance artist and made no secret of that fact.

Of the many incidents told about Harlan, a couple stick out in my mind (I’m not going to reference these; I don’t have the time at present to cite sources. Apologies.)

–Harlan ranting about the idiocy and ignorance wedded to preening hubris and arrogance of divers Hollywood executives and producers while receiving recognition for his writing at an awards banquet. In the audience that night: an un-named Hollywood insider clenching his fists and muttering, “I’m gonna kill him; I’m gonna kill him. . . .”

–Philip K. Dick—having had quite enough of Harlan’s harassment of a California bookstore’s staff—grabbing Ellison up in his bear-like arms and physically removing him from the premises. (Second favorite PKD vs. Ellison anecdote: PKD, having endured enough of Harlan’s bullying bitching, laying into him in public at a bar where friends of both were holding court, giving as good as he got, verbally.)

–Harlan’s awe-struck correspondence with James Tiptree Jr. (nee Alice Sheldon), lauding him (later: her) writing as “better than any of us”. (Of course, Harlan being Harlan—once Ms. Sheldon’s masquerade crumbled, he pushed her too hard to do various things he thought would better her career and artistic reputation. She retreated into offended silence.)

Though I never met him, I remember Harlan as an astonishing amalgam of manic energy and precise, polished word-smithery; as a sincere humanist and committed leftist-activist; as a litigious provocateur and feminist who (‘pon occasion, it seems) engaged in chauvinist behavior; as a man who bared his bi-polar soul to us re: his struggles with phonies and poseurs of all stripes, his own intensity level, his commitment to ofttimes painful truth-telling and unwillingness to hype substandard literary works that cost him a succession of powerful professional friends.

R.I.P. Harlan—You maddening, tortured, funny, talented, oft-times conflicted, searingly honest (whilst also, paradoxically, at times full of shit), performance artist soul.

You cared. You preached. You left behind a startling body of work.

You put your thumb on the scales with your life’s work.

You made a difference.

What more can any of us hope to accomplish, really?