The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials, by Wayne Barlowe

The Locus Awards were established in 1972 and presented by Locus Magazine based on a poll of its readers. In more recent years, the poll has been opened up to on-line readers, although subscribers’ votes have been given extra weight. At various times the award has been presented at Westercon and, more recently, at a weekend sponsored by Locus at the Science Fiction Museum (now MoPop) in Seattle. The Best Art or Illustrated Book Award was only given in two years, 1979 and 1980 and was won by Ian Summers for Tomorrow and Beyond. In 1994, Locus introduced the Best Art Book Award, which was won by Michael Whelan for The Art of Michael Whelan: Scenes/Vision. The category has been dominated by the Spectrum series, which has won in all except six subsequent years. In 1980. The Locus Poll received 854 responses.

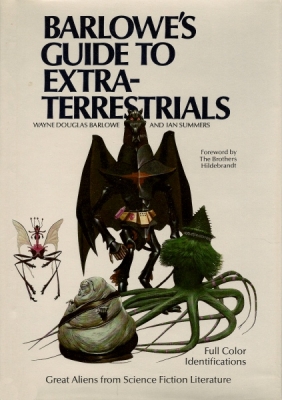

Wayne Douglas Barlowe and Ian Summers have created a catalog of aliens as described in numerous works of science fiction, by authors as diverse as Larry Niven, Ursula Le Guin, and Jack Vance. Each alien is according a two page spread in which the author and artist provide the name of the alien’s race, the author who created them and the work in which they appear and a full page image of the creature. The aliens are also described and frequently Barlowe has illustrated details of their hands, textures, or other things that make each race unique.

The book includes a fold-out centerfold that shows 48 of the aliens more or less at their relative sizes, from the wormlike Mesklinites from Hal Clement’s novel Mission to Gravity to Jack Williamson’s jellyfish-like Medusians from The Legion of Space. Summers admits that in many cases the size comparisons are approximate since the authors often just gave hints about an alien’s size relative to humans, who are also included in the comparison chart.

The pages devoted to the aliens includes, generally, physical descriptions, discussion of the habitats, culture, and occasionally other aspects of their physiognomy, such as reproduction or ecology, depending on the sort of information the authors provided in their novels and stories about the various aliens.

In some ways, the book has the feel of a sort of Monster Manual for a role playing game based on classic science fiction, although there are no stats for any specific game provided. The images, taken out of context and without any backgrounds, reinforce the impression.

The end of the book incorporates pencil sketches Barlowe created in trying to capture the images which he completed and used in the book. These line drawings, often with some descriptive notes, provides additional insight into Barlowe’s creative process, especially with the inclusion of some aliens of his own design, such as the Thype and Villar.

Although Barlowe revisited the concept of this book in 1996 when he published a similar Barlowe’s Guide to Fantasy with text by Neil Duskis, in some ways it feels like the time for a book such as this has vanished. One of the things both of Barlowe’s Guides relies on is a certain amount of consensual familiarity with the source materials. It doesn’t matter if an individual reader hasn’t read Piers Anthony’s Kirlian Quest because when this book was published it was assumed that, due to the relatively small amount of science fiction being published, readers would be familiar with key texts and writers, making this book a collection of old friends and some new ones. With the proliferation of science fiction and fantasy novels, and the addition of independently published books driving that number ever higher, it is more likely now than in 1979 to find fans whose reading habits have virtually no overlap.

That isn’t to say that an updated version of Barlowe’s Guides wouldn’t be welcome, bringing modern techniques to some of the races created by an ever-increasing number of authors over the past decades to supplement the work that Barlowe has already done.

Barlowe’s Guide to Extraterrestrials was also nominated for the Hugo Award for Best Non-fiction book, losing to Peter Nicholls’s The Science Fiction Encyclopedia.

The other top five art or illustrated books, out of the 100 that received nominations, included (in order of finishing) H.R. Giger’s Necronomicon, Alien Landscapes by Robert Holdstock & Malcolm Edwards, Wonderworks by Michael Whelan, and The Illustrated Harlan Ellison.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. His most recent anthology, Alternate Peace was published in June. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I don’t think I ever had this one, but I did have at least a couple of the Terran Trade Authority books, some other guide to aliens (I believe they were original, not sourced from other fiction) and one or two other coffee table-sized books along the same lines.

That’s a genre that seems to have vanished, isn’t it?

I loved Barlow’s Guide as a kid and used to page through it regularly, discovering aliens that I had yet to encounter in my reading. I still have my copy, which I originally picked up at a sidewalk sale sometime in the early 80s. Good stuff!