A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Paul Bishop on Lance Spearman – The Black James Bond

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

“You’re the second guy I’ve met within hours who seems to think a gat in the hand means a world by the tail.” – Phillip Marlowe in Raymond Chandler’s The Big Sleep

(Gat — Prohibition Era term for a gun. Shortened version of Gatling Gun)

Paul Bishop wrote the very first entry for our Discovering Robert E. Howard series (covering REH’s fight stories). I knew he’d come up with another great piece for the return of A (Black) Gat in the Hand – and boy, did he! I had never even heard of the Lance Spearman books, but what a cool story! Pulp magazines fell by the way-side for pocket paperbacks and comic books. Topics related to the latter two groups will be sprinkled in to this series. And today, Paul is going to tell us about a third entry: the popular ‘Look Books’ Read on!

‘Lance Spearman, has a charming way with girls and a deadly way with thugs’

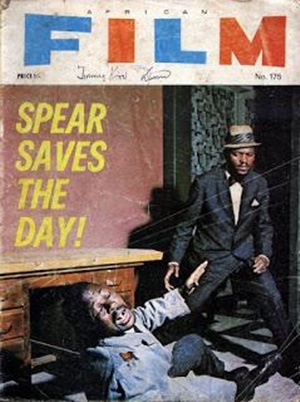

Look-books—a term coined for magazines featuring a mash up of action photographs accompanied by comic strip style captions (also known as photo books)—are relatively unknown in America. However, in many other parts of the world, this comic book hybrid of captioned action photographs had a rabid following from the ‘60s to the late ‘80s. In Africa, look-books served as surrogates for films—as a means to tell film-like stories— at a time when commercial African cinema was not yet invented.

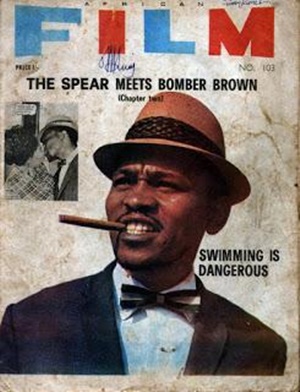

African Film Magazine (AFM) was the most popular of the African look-books. Alternately called Spear Magazine, every bi-weekly issue had eager fans clamoring for it at their local newsstand. Created by James Richard Abe Bailey, the character of Lance Spearman shattered racist stereotypes of the uncivilized, uneducated, spear-carrying Africans as portrayed in most Western comic books of the era. Each issue of AFM contained thirty-one pages of action filled black and white captioned photographs edited in urbane cinematic style.

AFM began publishing the Spear’s adventures during the African post-colonial era of the mid-sixties under the banner of Drum Publications. The magazine found immediate popularity, with every issue flooding across Anglophone Africa, from Nigeria and Ghana to South Africa, Zambia, Tanzania, Kenya and Uganda.

“Drum Publications — tired of the clichéd racist images of Black people in contrast to the heroic images of white soldiers and superheroes in Western comics — decided to create comic books that would appeal to Black men. They began photographing black men in adventures that were designed to appeal to the Black African population. ~ Balogun”

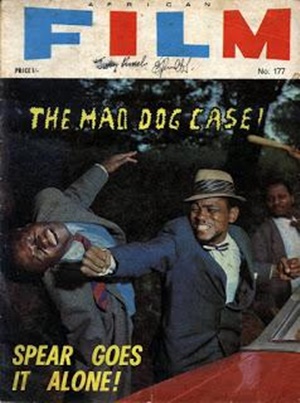

The responsibility for AFM’s phenomenal success rested squarely on the fictional adventures of one man—the dashing, straw-hatted, bow-tied, sport-jacketed, fast driving, Whiskey on the rocks drinking, cool cat, Lance Spearman—the black James Bond. A decade before Shaft redefined cool for American audiences, the Spear was out Bonding Bond, battling an ever more outrageous array of colorful, over-the-top evil villains with every issue.

The responsibility for AFM’s phenomenal success rested squarely on the fictional adventures of one man—the dashing, straw-hatted, bow-tied, sport-jacketed, fast driving, Whiskey on the rocks drinking, cool cat, Lance Spearman—the black James Bond. A decade before Shaft redefined cool for American audiences, the Spear was out Bonding Bond, battling an ever more outrageous array of colorful, over-the-top evil villains with every issue.

An expert marksman, skilled at karate and boxing, the Spear (as he was nicknamed) is a rollicking combination of African super-spy, detective, and superhero. He rocks a goatee, smokes expensive cigars, drinks good Scotch, and dresses in well-tailored suits complete with bow tie and Panama hat. He likes his women buxom and his cars fast—particularly his Corvette Stingray. His favored handgun is a Beretta he calls my little friend.

“He is the black James Bond and the most popular fictional character in Africa today… ~ Stanley Meisler, Los Angeles Times foreign and diplomatic correspondent, 1968.”

Virtually leaping off the pages of AFM, the Spear captured the dream of a new generation of urban African youth. These were young men and women who left their villages for the cities in search of a better life. The Spear became a touchstone, helping to shape their view of their place in an empowered new world.

The Spear was Western hip without losing or hiding his distinctly African cultural identity. Eating fine foods, loving beautiful women, the Spear possessed a slightly arrogant, self-confident, easy talking style, which made him equally at home mingling in high society or fighting dirty in a back-alley street.

Lance Spearman spoke directly and individually to so many of those who followed his adventures. He created an idealized view of modern Africa, delivering regular doses of self-esteem, personal dreams, and hope to readers searching for relevant role models.

“My mother was an ardent reader of this magazine. She would make sure every week she bought a copy at Kingstone Bookstore next to Shoprite on Cairo Road. Our home was like library, friends would come to read these. ~ Chris Phiri”

Employing budget conscious improvisational methods (the trademark Corvette Stingray was often a photo of a Dinky Toy), the Spear’s adventures were captured through vibrant action-filled photographs. This alternative to the poorly drawn comic art available at the time available created a do-it-yourself movement of self-reliance, producing an attitude eventually assimilated into Nollywood movie making as well as the coming explosion of ‘70s era Blaxploitation in America.

At the peak of AFM’s bi-weekly popularity, Lance Spearman had over half a million fans across Africa. At that time, AFM printed 30,000 copies of each fourteen-cent magazine. Every issue consistently sold out, creating an active and lucrative second-hand market.

“The overloaded phrase, ‘second-hand Good Samaritan’, meant the person who lent us a copy had borrowed it from somebody, who had borrowed it from somebody, etc. etc. So we read it as, not second but, tenth or even twentieth-hand. All of which meant by the time it reached us, it was in hardly readable tatters! ~ Ingina y’Igihanga”

Compared to today’s multi-millions of fans who hang on every hundred- and forty-word belch from celebrity Twitter feeds, a mere half a million fans may be considered negligible. However, the Spear earned his half million Lancers in the ‘60s—before the Internet was even the spark of an idea—in a time when people wrote letters by hand with no conception of e-mail. From that perspective, Lance Spearman was a celebrity god.

Surprisingly, considering the ethnic centered politics of the era, the photographic and writing forces behind Lance Spearman were a multi-racial team effort. Omitting any reference to their actual South African headquarters (company info inside the magazines indicated offices in the less controversial Kenya and Nairobi), Drum Publications became a valuable training ground for emerging African writers such as Can Themba, Nat Nakassa and Nigeria’s Nelson Ottah. Along a number of students from the University of Lesotho—who were also given their entre into magazine writing—were paid $65 per Lance Spearman story.

Due to a fear of apartheid censorship, Drum publisher Jim Bailey avoided any stories of a racial or political nature. He also published several different versions of the magazine, which contained the same interior stories, but under different titles to fit the varying demographics between South Africa and East and West Africa.

“These were the comics of our time! You would do anything to get the latest series. Often we had to wait in line to borrow from a friend who had one—even do their home chores if need be! The one I liked most was when Zollo tied Spear on a rope and lowered him into this big boiling pot, but of course Spear escaped. Hahaha…Made us love reading. ~ Sewanywa Sekiswa”

The finished stories were sent to Johannesburg, South Africa, where Malcolm Dunkfeld, a white South African, oversaw the editing. From there, the scripts were sent to Swaziland where black cameramen under the direction of white photographers Stanley N. Bunn and Trevor Barrett, staged and shot the scenes from the stories. Finally, the completed issues were mastered and printed in London before being shipped back to South Africa for distribution.

The finished stories were sent to Johannesburg, South Africa, where Malcolm Dunkfeld, a white South African, oversaw the editing. From there, the scripts were sent to Swaziland where black cameramen under the direction of white photographers Stanley N. Bunn and Trevor Barrett, staged and shot the scenes from the stories. Finally, the completed issues were mastered and printed in London before being shipped back to South Africa for distribution.

Filling the roles of the characters in the stories was a troop of amateur black actors. These included Jore Mkwanazi, the man who would become the embodiment of Lance Spearman. A former houseboy, Mkwanazi was discovered playing piano in a nightclub by Stanley N. Bunn on of the directors of photography.

Bunn saw in Mkwanazi’s features the tough, cynical, sophisticated look he believed was needed for the role of a black super-spy. Skyrocketing from earning $35 a month for scrubbing floors to $215 monthly, Mkwanazi exploded into the African consciousness, becoming an indelible black liberation icon.

“Yeah, my hero. Dapper with Scotch-on-the-rocks his favourite drink. There is his Little Friend—a Beretta in a holster under his well-tailored suit. He smokes expensive cigars and wears a panama hat. In later editions, his most trusted allies were Sonia, a karate kicking baaad lady, a catapult wielding youngster named Lemmy, and a uniformed police officer Captain Victor… ~ Sulubu Tuva”

The Spear also surrounded himself with loyal action-ready allies. Closest to him was his agile assistant, Sonia, a high kicking, karate chopping beauty who was never a damsel in distress. Lemmy, who never missed a target with his catapult, was the Spear’s young sidekick, who provided a vulnerable and humanistic edge to the stories. There was also the bulky strength and tenacity of the quick-thinking Capitan Victor, who often provide the Spear with backup.

With the help of Sonia, Lemmy, and Captain Victor, readers could always trust the Spear to escape from any situation no matter how dire. This was a fearsome foursome to be reckoned with, their respect for one another providing yet another positive influence to come from the series.

“The dialogue was hip and contemporary, in the manner of the racy thrillers of James Hadley Chase, the hottest writer we cherished back then. The lines were indeed riveting such that one readily committed them to memory that lasts to this day. For instance, the thug bearing down on Sonia gets the following words from Spear as he steps forward for a fight: “Woman-beater, try me for size!” Before the hoodlum can get to the races, Spear lands him the sucker-punch, saying: “You have a glass jaw!” With the fallen thug crying “Aaaaaargh!” Lemmy would congratulate Spear thus: “Attaboy, Spear!” ~ Uzor Maxim Uzoatu”

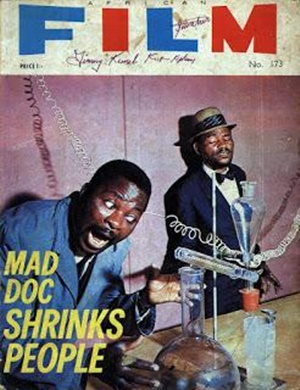

Then there were the Spear’s colorful enemies. Described as menace in overdrive, Rabon Zollo bore a hideous black eye-patch over his missing eye. The Hook-Hand Killer, who obviously killed using the evil hook on his hand. Dr. Devil, a criminal mastermind whose electronic wizardry threatened to direct international experimental rockets off course. Mad Doc, an insane inventor who created a serum with the power to shrink people. Professor Thor used a vile machine to read minds, while Professor Rubens used the organs of animals to produce a werewolf.

Then there were the Spear’s colorful enemies. Described as menace in overdrive, Rabon Zollo bore a hideous black eye-patch over his missing eye. The Hook-Hand Killer, who obviously killed using the evil hook on his hand. Dr. Devil, a criminal mastermind whose electronic wizardry threatened to direct international experimental rockets off course. Mad Doc, an insane inventor who created a serum with the power to shrink people. Professor Thor used a vile machine to read minds, while Professor Rubens used the organs of animals to produce a werewolf.

There were also other villains, such as Themermolls, Countess Scarlett, and The Head Huntress. But the menace of The Cat presented Spear with possibly his greatest challenge—a black-masked cat burglar who used clawed gloves to scale any building or rip to shreds anyone who tried to stop him. Battling them all, Spear was always the colossus positive force who would save the world.

“Lance Spearman was our own James Bond, Jason Bourne, Jack Bauer all rolled into one… ~ Jimmy Mungai”

With their combination of extreme cartoon-like violence and influences from early Hollywood melodramas, AFM and other look-books were important precursors to the emergence of African cinema. They also had influence on the rise of African crime fiction—readers of Lance Spearman finding needed encouragement to create heroes of their own in a world of black nationalism.

1972: After one hundred and fifty issues, AFM suddenly disappeared from the newsstand without any official explanation. The politics of apartheid were the most likely cause, as used copies of the magazine also disappeared from the mainstream becoming a valuable covert smuggling commodity. However, the strongest rumor among devastated fans was Lance Spearman had died—or at least the actor who portrayed him. None of this has ever been confirmed, but loyal readers of the Spear’s adventures refused to believe he was dead.

“Spear could never die, we told ourselves. We had to make do with smuggled back issues of African Film dating back to the 1960s and even the years covering the 1967-70 duration of the Nigeria-Biafra War. We devoured the back issues waiting for the inevitable day that the unbeatable Lance Spearman would make a triumphant return, as it stood as a given to us that his death was quite impossible. ~ Uzor Maxim Uzoatu”

While Lance Spearman is criticized in politically correct circles for his perceived stereotypical portrayal of blackness and masculinity, his adventures were ultimately responsible for raising the self-esteem and personal consciousness of a generation of readers. There could be no more beautiful or positive legacy.

Prior posts in A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2019 Series

Back Deck Pulp Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand Returns

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Will Murray on Doc Savage

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Hugh B. Cave’s Peter Kane

A (Black) Gat in the Hand – 2018 Series

With a (Black) Gat: George Harmon Coxe

With a (Black) Gat: Raoul Whitfield

With a (Black) Gat: Some Hard Boiled Anthologies

With a (Black) Gat: Frederick Nebel’s Donahue

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Walsh

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – January, 1935

A (Black) Gat in the hand: Norbert Davis’ Ben Shaley

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: D.L. Champion’s Rex Sackler

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Dime Detective – August, 1939

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #1

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: W.T. Ballard’s Bill Lennox

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Day Keene

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – October, 1933

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #2

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Black Mask – Spring, 2017

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Frank Schildiner’s ‘Max Allen Collins & The Hard Boiled Hero’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Campbell Gault

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: More Cool & Lam From Hard Case Crime

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: MORE Cool & Lam!!!!

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Thomas Parker’s ‘They Shoot Horses, Don’t They?’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part One)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe Bonadonna’s ‘Hardboiled Film Noir’ (Part Two)

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: William Patrick Maynard’s ‘The Yellow Peril’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Andrew P Salmon’s ‘Frederick C. Davis’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Rory Gallagher’s ‘Continental Op’

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #3

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #4

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Back Deck Pulp #5

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: Joe ‘Cap’ Shaw on Writing

A (Black) Gat in Hand: Back Deck Pulp #6

A (Black) Gat in the Hand: The Black Mask Dinner

Paul Bishop was a highly decorated officer who spent thirty-five years with the Los Angeles Police Department. He’s written several novels and is the driving force behind the Fight Card series of pulp-style boxing novellas. And if you like Westerns, 52 Weeks – 52 Western Novels: Old Favorites and New Discoveries is a real treat!

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He organized ‘Hither Came Conan,’ as well as Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he contributed to The New Adventures of Solar Pons.

Wow. Really interesting stuff. I was always intrigued by the idea of the Italian photo-novels. I had never heard of these.

Blee – Yeah: this was entirely new to me. An interesting alternative to comics and novellas. I’d like to read one some time.

Oh how I would love a hefty anthology of reprinted Lance Spearman adventures!

And oh how unlikely it is that such a thing could ever come to pass.

You have to register with the New York Times (to read anything there, I believe), but here’s a 1970 Times article on Spearman.