Teaching and Fantasy Literature: Hazards of Teaching Cool Stuff You Love in a Classroom

“Why do we have to read so much?” said the students who thought Intro to Myth would be an easy A. “And all this writing! You turned it into work!”

“Why do we have to read so much?” said the students who thought Intro to Myth would be an easy A. “And all this writing! You turned it into work!”

“Why are you asking us to think critically about mythology, of all things?” said the students who regarded stories only as entertainment. “I want to read this stuff the same way I read watered-down versions of it when I was ten.”

“Why are you making us read The Silmarillion?” said the less reflective of the Tolkien fans. “I’ve read The Lord of the Rings twenty times, and I thought I could get college credit for stuff I already did in high school.”

Alas, one side effect of attending college is that one may be asked to do college level work. Most of my students were good sports about it. I assured the students who weren’t that they were welcome to keep their copies of the syllabi and read the same books for kicks on their own, and they could get out of the bother of keeping pace, writing papers, or thinking about what they read. All they had to do was go to the registrar’s office and withdraw from my class. Nobody was making them stay.

Nearly all of them stayed.

As I related in my last blog post, my favorite experience teaching in a classroom setting started as a satire-worthy departmental turf war, and ended up as something intermittently sublime.

The blackboard told me more about that class than about any other I taught. The students’ questions had just never called for many diagrams in my composition and poetry classes. One week, the blackboard bore maps of various otherworlds–Hades, the circles of Dante’s Hell, Beleriand. Every session, somebody needed help with chronology (Gilgamesh got into written form before Genesis did, Blake and Milton were not contemporaries, Tolkien and H.D. both wrote their major works during WWII, and so on). And when characters had extra names, we needed tables to keep track of who was who. By the time we got to The Silmarillion, my students knew to keep track of the several names Tolkien gave his Lady of Stars. At the end of every class meeting, I would look at the blackboard and think, If I had walked into this room as an undergrad and seen those class notes, I’d have chased the professor down the hall and begged to know what the class was and how I could get into it.

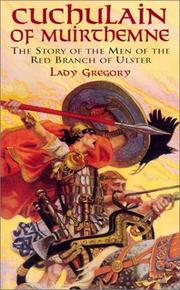

As lovely as it was to teach exactly the class I would have wanted to take, it was my students’ class, too. They agreed with me that Cuchulain’s fits of battle madness were awesomely bizarre–who could fail to be impressed by a guy who raged so mightily that, on a regular basis, one of his eyes would get sucked back into his skull while the other popped out of its socket and a great fountain of blood shot straight up out of his head?–but they never quite connected with the great 12th century Irish epic The Cattle Raid of Cooley. All that fuss over the theft of one ox!

As lovely as it was to teach exactly the class I would have wanted to take, it was my students’ class, too. They agreed with me that Cuchulain’s fits of battle madness were awesomely bizarre–who could fail to be impressed by a guy who raged so mightily that, on a regular basis, one of his eyes would get sucked back into his skull while the other popped out of its socket and a great fountain of blood shot straight up out of his head?–but they never quite connected with the great 12th century Irish epic The Cattle Raid of Cooley. All that fuss over the theft of one ox!

Okay, but what might the ox mean to the characters, to the original audience, or to Yeats?

There were two ways the students preferred to read: with thudding literal-mindedness, and in a floating bliss of unconscious receptivity. These are both useful, important, and worthy modes of reading. They just don’t happen to be the modes of reading that suit college-level study. I can’t blame my students for regarding with suspicion my efforts to get them to think critically about stories they would have preferred simply to love or to judge. They feared they would lose modes of thought they valued if they learned a new approach, and that does sometimes happen.

To the extent that I got anywhere at all with that fear of theirs, it was by offering them a new form of joy. The beginner’s version is a game of spot-the-allusion. At our big state university, many of the students had never had a chance to play this game with any success. They had been asked to play it with texts like Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” but never had they been led to “The Waste Land” by way of the ancestor texts they would have needed to make sense of it. Eventually I was able to cajole most of them beyond spot-the-allusion to a game of why-the-allusion.

To the extent that I got anywhere at all with that fear of theirs, it was by offering them a new form of joy. The beginner’s version is a game of spot-the-allusion. At our big state university, many of the students had never had a chance to play this game with any success. They had been asked to play it with texts like Eliot’s “The Waste Land,” but never had they been led to “The Waste Land” by way of the ancestor texts they would have needed to make sense of it. Eventually I was able to cajole most of them beyond spot-the-allusion to a game of why-the-allusion.

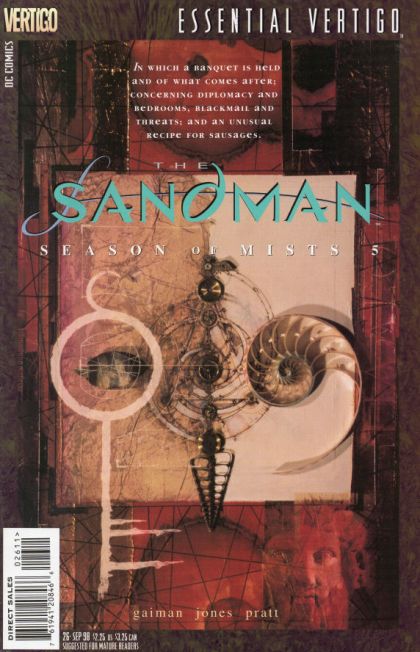

What could Tolkien possibly have been thinking when he wrote the stiffly formal creation stories of Middle Earth? Why does The Silmarillion feel so different from The Lord of the Rings? Well, Tolkien’s choices make a whole lot more sense when you have the pages of Genesis and the Theogony open on your desk right next to the pages of the “Valaquenta.” Where did Gaiman get all the characters in the “Season of Mists” volume of The Sandman? By the time we reached the end of the syllabus, we had spent enough time with Paradise Lost and Yeats’s fairy folklore to talk about how and why Gaiman might have decided which lost gods should vie for the key to Hell.

It still surprises me how few of the final projects tried to wrestle with the hows and whys from the inside. I offered the kids the chance to do creative writing for the final paper, and most of them opted to write twelve-page research papers instead. The big draw was that they got to put their own favorite works of popular culture into our somewhat arbitrary canon of texts-that-fit-into-one-semester and texts-that-don’t-serve-a- departmental-turf-war. Freedom to add anything they wanted to our classroom canon shook awake a lot of students who had initially resisted the work of the class. The paper about William Blake, the Gnostic Gospels, and the horror film Dark City was probably the single best piece of student writing I saw in seven years of classroom teaching, and I got to see it take shape through a series of spectacularly rough drafts.

It still surprises me how few of the final projects tried to wrestle with the hows and whys from the inside. I offered the kids the chance to do creative writing for the final paper, and most of them opted to write twelve-page research papers instead. The big draw was that they got to put their own favorite works of popular culture into our somewhat arbitrary canon of texts-that-fit-into-one-semester and texts-that-don’t-serve-a- departmental-turf-war. Freedom to add anything they wanted to our classroom canon shook awake a lot of students who had initially resisted the work of the class. The paper about William Blake, the Gnostic Gospels, and the horror film Dark City was probably the single best piece of student writing I saw in seven years of classroom teaching, and I got to see it take shape through a series of spectacularly rough drafts.

I don’t expect ever to teach a class like it again. Indeed, one of the many reasons I left academia was that I had no patience left for the kinds of turf wars that got me that teaching gig in the first place. Without the artificial constraints that arose from that turf war, would I still choose the texts that gave the syllabus its best juxtapositions? Without the massive distortion field of the grade, and the imperative to assign stuff that can be graded, it would make no sense to write a final exam. Yet my preparation to write the final exam gave me one of the most joyful moments of my teaching life, when I imagined I glimpsed, so briefly, the whole cosmos of myth.

Sarah Avery’s short story “The War of the Wheat Berry Year” appeared in the last print issue of Black Gate. A related novella, “The Imlen Bastard,” is slated to appear in BG‘s new online incarnation. Her contemporary fantasy novella collection, Tales from Rugosa Coven, follows the adventures of some very modern Pagans in a supernatural version of New Jersey even weirder than the one you think you know. You can keep up with her at her website, sarahavery.com, and follow her on Twitter.

I would have taken this class. It sounds absolutely great.

I wonder, did that student ever put his paper online or put it in a magazine or something? You know, that paper “about William Blake, the Gnostic Gospels, and the horror film Dark City?” I’m interested to read it, actually.

If you ever see that student again, tell them to put up their paper on this website, or somewhere!

Thanks! It was a total blast. If all the courses I taught had been as much fun, I might never have made it back to writing fiction.

I haven’t seen that student in over a decade. I’d recognize him anywhere, though. He was a delight to work with.

[…] reached “The Tale of Beren and Luthien,” my Intro to Myth students forgave me for dragging them through the drier, more mythographic early stretches of The Silmarillion. (“It’s as bad as the […]