A Slender, Forgotten Gem: The Deep by John Crowley

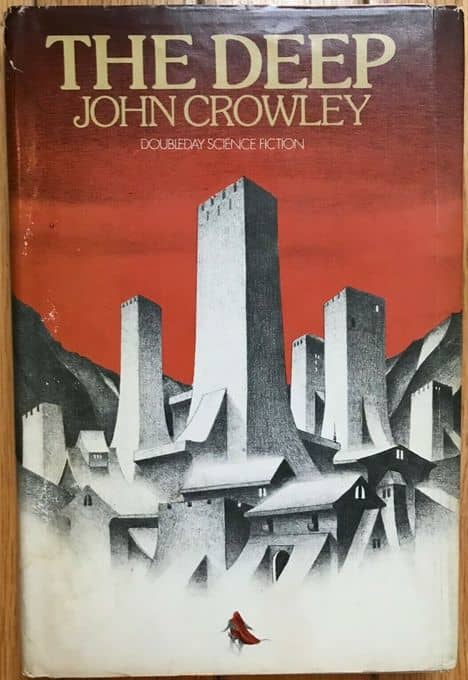

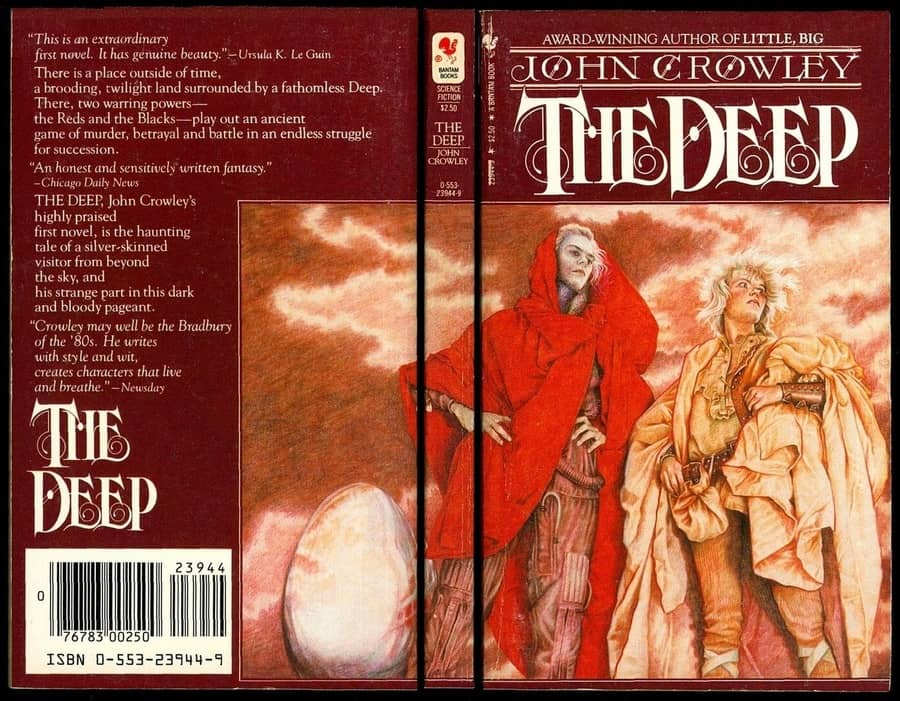

1984 Bantam paperback edition; cover by Yvonne Gilbert

Some authors create slender, nearly flawless works of fiction. Books like little jewels on the shelf — cut just right, gleaming, standing alone. Beagle managed this a few times: A Fine and Private Place, The Last Unicorn. Goldman turned his into a movie that was nearly as good: The Princess Bride. Swanwick and Wolfe have done it with literary science fiction: Stations of the Tide and The Fifth Head of Cerberus, respectively. The Deep is a book like this: finely wrought, chiseled, alien.

Is this tiny 1975 volume science fiction or fantasy? On the one hand, the book starts with the Visitor, a damaged android who arrives in the book’s world with no memory of what he is or his mission. But the world he’s in, the culture and factions of which his ignorance provides the perfect excuse for a narrator’s artful explanation, is purely fantasy: a kingdom riven by conflict between Reds and Blacks, with a city at its center and wild wastes surrounding, ringed on all sides by the Deep.

The world, as different characters explain at different times, is a platter or a plate suspended on the Deep by a great pillar. And even when the android journeys to the edge of this world and meets the Leviathan who dwells there, when he learns the nature of the engineered conflict and how humans were first settled on the world, Crowley doesn’t ever default to pure science fiction. Even if the reader can credit a resettled humanity in the far future, reset to medieval technology with continual wars to control the population, the story still leaves you with a flat world upon the Deep. Somehow, this central oddity works; it keeps a surreal wrinkle in the heart of the world Crowley creates.

[Click the images for deeper versions.]

|

|

1975 Doubleday hardcover edition; cover by John Cayea

The human characters read like a cast from a Wonderland reinterpretation: Old Redhand, Redhand, Younger Redhand, Red Senlin, Sennred, Carred (all Reds, obviously), King Little Black, Black Harrah, Young Harrah (some of the Blacks). This naming scheme means I found myself flipping back to the character list provided at the beginning of the novel a few times, especially in the first few chapters before it became clear who was central to the story and how the different alliances were playing out. Besides the Visitor, whose story arcs across the narrative like a wandering star, the story is about Redhand, his role in making and unmaking kings, and his desire for fidelity — to his wife, his oaths, his land.

Where Crowley excels, and what makes the book so memorable, are the descriptions, both of people and scenes, running through the book. There are moments of iridescence in the language itself. The story seems almost secondary to Crowley’s love of words, an excuse for the language itself.

There are no dramatic shifts or twists as the plot develops. The Visitor’s answers at the edge of the Deep and Redhand’s ultimate revelation and eventual fate all seem inexorable. Indeed, when there are major developments, as when Redhand’s father is killed and the Red claimant to the throne suffers a sudden reversal, the novel seems to lurch forward abruptly. For all that though, the book remains a slender, forgotten gem.

Stephen Case has published fiction at Beneath Ceaseless Skies, Orson Scott Card’s Intergalactic Medicine Show, and Daily Science Fiction. His reviews have appeared at Fiction Vortex and Strange Horizons, as well as his own blog, stephenreidcase.com. His last article for us was a review of Linda Nagata’s Edges.

Another book to add to my backlog. Thanks Steve, I will keep an eye out for it.