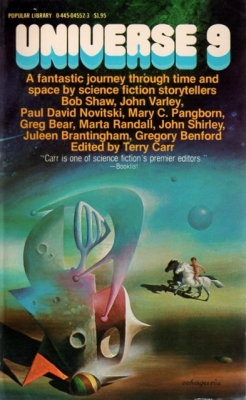

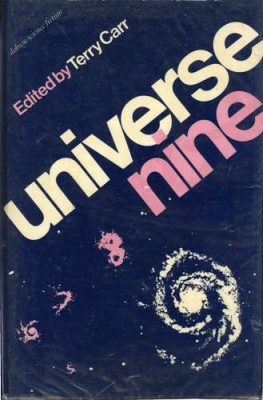

The Golden Age of Science Fiction: Universe 9, edited by Terry Carr

The Locus Awards were established in 1972 and presented by Locus Magazine based on a poll of its readers. In more recent years, the poll has been opened up to on-line readers, although subscribers’ votes have been given extra weight. At various times the award has been presented at Westercon and, more recently, at a weekend sponsored by Locus at the Science Fiction Museum (now MoPop) in Seattle. The Best Anthology Award dates back to 1976, although it was not presented in 1978. The inaugural award went to the anthology Epoch, edited Roger Elwood and Robert Silverberg. The 1980 award was won by Terry Carr for Universe 9. It was Carr’s third win in a row, with his first two being for entries in his Terry Carr’s Best Science Fiction of the Year series. The Locus Poll received 854 responses.

Terry Carr’s Universe series of anthologies ran for 17 volumes, beginning in 1971 and only ending with Carr’s death in 1987. During that time, he also edited 16 volumes of Terry Carr’s Best Science Fiction of the Year, five volumes of Fantasy Annual, and two volumes of The Best Science Fiction Novellas of the Year. Sixteen of the volumes of Universe ranked in the Locus Poll (only Universe 7 missed out), and Carr won the Locus Poll for entries of Universe for volumes 1, 4, and 9. In four years, Carr’s best of year anthology beat out his own Universe anthology in the poll.

The anthology opens with Bob Shaw’s “Frost Animals,” the longest story in the book. It is a murder mystery in which the prime suspect has been away from Earth for 18 years, although due to relativistic effects of space travel, only thirteen months have passed for him. With the accused murderer the main character, it is reasonably clear that he didn’t commit the crime and the actual murder and murderer are of lesser interest in the story, although a science fictional method is used. What mostly sets this story apart is its exploration of the impact of the “time slip” experienced by Dennis Hobart upon his return, especially as people who are fresh in his memory have little recollection of someone they haven’t see in nearly twenty years.

Of the authors included in this anthology, I was familiar with all of them with the exception of Paul David Novitski, who was also an active fan artist in the 60s and 70s using the name “Alpajpuri”. He only published a handful of stories, beginning with “The Wind She Does Fly Wild” in Amazing Stories in 1973. “Nuclear Fission” was his penultimate fiction appearance, with his last, “Illusions,” appearing a month later in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine. His story in this anthology, “Nuclear Fission” is really more a slice of life than a story, loosely exploring a world as yearned for by the commune movement of the 1970s. Novitski tacks on a level of gender equality and neutrality to the culture as well.

Gregory Benford postulates that the grooves made on pottery could, theoretically, capture the sounds around them the same way a phonograph records inscribes wax in “Time Shards.” In the story, the research has already been done and the scientist is demonstrating its success to his patron, playing a thirteenth century English pot. John Hart views his experiment as a failure because, although he has successfully proven the voices can be captured, the conversations he has caught are so banal, demonstrating the need for an historian when a scientific project into historical sources occurs.

Marta Randall explores what happens to the captain of a colonization starship when her skills are no longer needed. “The Captain and the Kid” is set in the period after the ship has landed and the colonists have not only been thawed, but are starting to build a farming community. With a limited number of colonists, everyone must pull their weight, but the arrogance of the captain, who sees farming as beneath her, gets in the way of her acceptance by the community, just as she can’t accept any role the new colony requires of her.

Mary C. Pangborn’s “The Back Road” is an interesting mix of science and advancement and country magic. Set in a remote part of New England, Henry Waldron really just wants to be left alone. Working to his advantage and seclusion is the titular backroad, which his grandson describes as a moebius strip of a road. Although it looks like a shortcut back to civilized places like Boston, people who take the shortcut find themselves disappeared form the world as we know it. When men from the government come to discuss buying Waldron’s land for use to build a scientific lab, Waldron doesn’t want to sell and makes his opinion known. The government men threaten him with eminent domain and in the end he agrees to think about it, leading them back past the back road to make sure they get back home, although that short cut does look mighty tempting.

John Shirley offers up the sport of waveriding in“Will the Chill,” as well as Tondius Will, the champion with the titular nickname. Will is anything but outgoing, apparently living only for the sport to the length that when given a choice of losing, but saving his girlfriend’s life, or winning and killing her in the process, he chose the latter. Now, several years later, he finds himself in a competition with an opponent who barely plays by the rules and seems to have the intent not only to win, but to kill Will in the process. Asked about his long-lost love in a pre-Contest interview, her death also weighs on his decisions as he works to defend his title. The story has some interesting ideas in it, but Shirley doesn’t quite focus the short story’s attention well enough.

Juleen Brantingham offers a warning against the rise of corporate Amerca in “Chicken of the Tree.” Written as a fable with a group of well-defined characters who may or may not be animals, Brantinham’s narrator likes to eat healthily and is concerned about the environment. An unpleasant encounter with a new corporate supermarket, when she thought she was entering a grocery store, leads her to guide her roommates out of the growing city into the countryside, where the is healthier food, air, and water, only to see the city slowly encroaching on their newly found utopia.

“The White Horse Child,” by Greg Bear, is yet another rural fantasy story. This is a story about the power of stories. When strangers begin to tell stories to a young boy, his family begins to get nervous, identifying the strangers as the same couple who told stories to his uncle years ago, resulting in him moving away from their safe, familiar community, to disappear into the hedonism of the big city. The boy’s religious aunt is called in to save his soul, making the story a battle between the lore of the old ways and the modern Christian religion (sans Bible, which has too many stories).

When John Varley’s “Options” was first published, it may well have been a ground-breaking look at gender, but forty years later, the story, which was nominated for the Hugo and Nebula Awards, feels somewhat naïve, having dated in the face of a changing society. Set in Varley’s Eight Worlds continuum, it looks at a woman who is looking into the idea of a sex change, despite her husband’s reluctance to embrace the idea. While Varley notes that easy and reversible sex changes have begun to level the economic and social playing field, the gender politics in Cleopatra and Jules family seems mostly regressive. Even as Cleopatra tells Jules that she is happy with their life, she continues to look into her options, indicating that the problems run deeper than she is willing to admit.

Three of the stories in the book, by Randall, Pangborn, and Brantingham, have never been reprinted. Shaw’s story has only been reprinted in English in one of Shaw’s collections (although it has been translated into French and Italian). Novitski’s story has been reprinted in an anthology of gay and lesbian science fiction, as well as translated into German. Shirley’s “Will the Chill” was reprinted in one of Shirley’s collections and was also reprinted by Paula Guran. Benford’s story appeared in Carr’s The Best Science Fiction of the Year #9 as well as two of Benford’s collections and Lightspeed, as well as translations into Dutch, French, and Italian. Bear’s story has frequently been reprinted. “The White Horse Child” was picked up for Fantasy Annual III, has appeared in four of Bear’s collections, as well as anthologies edited by Stephen R. Donaldson, Margaret Weis, and Isaac Asimov. The story has also appeared in Spanish, Japanese, and Italian. The final story in the book, John Varley’’s “Options,” which is set in his Eight Worlds series, was picked up by both Donald A. Wollheim and Terry Carr for their best of year collections, Included in two of Varley’s collections, reprinted in at least three other anthologies, and has been translated into German, Dutch, and French. It was also nominated for the Nebula Award and the Hugo Award and came in second in the Locus Poll, losing to George R.R. Martin’s “Sandkings” for all three awards.

The other top five collections for the Locus Award included (in order of finishing) The Best of New Dimensions edited by Robert Silverberg, The Best Science Fiction of the Year #8 edited by Terry Carr, Amazons! Edited by Jessica Salmonson, and Chrysalis 3 edited by Roy Torgeson. Carr also held the number 6 spot on the list with his The Best Science Fiction Novellas of the Year #1.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a sixteen-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for 8 years. He has also edited books for DAW and NESFA Press. He began publishing short fiction in 2008 and his most recently published story is “Webinar: Web Sites” in The Tangled Web. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference 6 times, as well as serving as the Event Coordinator for SFWA. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

It’s curious that the only one of those stories that has stuck with me is “Time Shards”, which I think is exceptional. I also like “Options”, but I agree with you that it comes off a bit dated.

I had — still have! — the middle editon, from Popular Library.