Embers to Ashes: Earth Abides by George R. Stewart

|

|

Maybe it’s just the times we live in, but I increasingly find myself drawn to narratives of defeat: Confederate military memoirs, histories of the Decline and Fall of This and That, accounts of Napoleon’s retreat from Moscow or Custer’s Last Stand. I suppose that’s why this summer, forty years after I blew it off when it was assigned in one of my first college classes, I finally got around to reading Earth Abides.

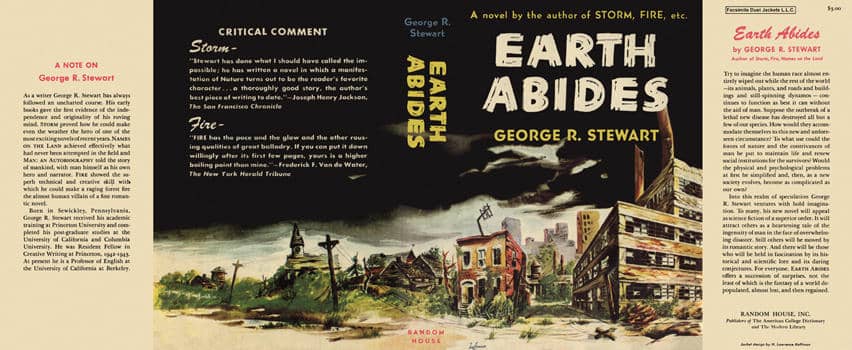

George R. Stewart’s 1949 post-apocalyptic novel is one of the most famous one-offs in the history of science fiction; it won the first International Fantasy Award in 1951, and in all the decades since, the book has rarely been out of print.

Stewart was primarily an English professor and historian and an only occasional novelist. In his first specialty he wrote books on English verse technique and composition; in the latter his most well-known works are a history of the Donner party, Ordeal by Hunger (1936), and a finely detailed, minute-by-minute account of the climax of the battle of Gettysburg, Pickett’s Charge (1959). Storm (1941) and Fire (1948), two novels Stewart wrote before his sole foray into science fiction, show his concern with large, impersonal forces and their effects on the enduring land and the ephemeral creatures that inhabit it. His most famous book takes that scientific detachment and interest in process many steps further, to powerful effect.

Earth Abides tells the story of Isherwood Smith, a young college student who lives in Berkeley, California. When the book begins, Ish is camping in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, doing the fieldwork necessary for his graduate thesis, The Ecology of the Black Creek Area, intended to be an investigation of “the relationships, past and present, of men and plants and animals” in the region. The thesis will never be written, though Ish will spend the rest of his life wrestling with fundamental questions regarding the connections between human beings and the natural world they so briefly occupy.

[Click the images for Earth-sized versions.]

On the book’s first page, two things happen that have effects far beyond any that Ish could anticipate: while scaling a cliff, he finds a miner’s hammer that someone had dropped there long before, and he is bitten by a rattlesnake. He retains the hammer without really knowing why, and after sucking out the snake’s poison, he finds an abandoned cabin and there lapses into a delirium, too weak and ill to leave. He seems to be sick with something other than merely the snakebite but of course is in no position to determine what that might be.

One day during his convalescence, two men enter the cabin, but as soon as they see its obviously ill occupant, they immediately flee in apparent terror before Ish can even speak to them. Once he recovers sufficiently to be able to make his way into a nearby town, he understands why the men reacted as they did. The town is empty. Its only remaining occupants are the dead, some of whom lie unburied in the streets, and in the eerily vacant buildings that he explores, Ish finds newspapers that reveal what has happened. While he lay prostrate in his isolated cabin, a previously unknown disease has suddenly appeared and in the space of just a few weeks, it has virtually wiped the human race off the face of the Earth.

This must have been the illness that laid Ish low. Why didn’t it kill him, as it did virtually everyone else? Did the snakebite somehow immunize him or did some other factor cause him to be spared? Ish will never have a definitive answer to the question and, in any case, what does it matter now?

|

|

Using an appropriated car, Ish makes his way back to the house in Berkeley where he lived with his parents, now just an empty building on an empty street in an empty city poised on the edge of an empty continent. In some ways, things aren’t too bad; there’s canned and dry food aplenty, and thanks to the automated systems that mankind lavished its limited foresight upon, the water still flows from the faucets and the electricity still courses through the wires – at first, anyway.

True, there’s no one to talk to, but in some ways Ish finds himself singularly well-suited to this new, solitary existence. Always a self-sufficient loner, he spends little time grieving, either for his presumably dead parents (who left no message behind for their son, no indication of where they went or what happened to them) or for the vanished human race and its millennia-spanning civilization, its seemingly unstoppable progress now forever halted.

Ish soon determines to see whether anyone else is left alive. After carefully choosing and equipping a vehicle, he drives across the continent, and in the course of his travels he occasionally encounters a stray person or two. Some flee in terror, mentally or emotionally unhinged by the catastrophe. Some are suspicious and threatening. Some are sunk in apathy, and some, like a group of sharecroppers he meets in Arkansas, are coping with the changed realities fairly well. In New York City, he spends an evening in a candlelit apartment (“The electricity had failed immediately, because the dynamos which supplied New York had been steam-driven”) playing cribbage with a pair of slightly dazed urbanites, Milt and Ann. Ish cannot bear to stay with them long; they clearly have no future, and the vast, indifferent mechanism that has eliminated the rest of the human race will inevitably find them too, and when it does, it will find them sadly ill-prepared:

He doubted whether they could survive the winter, even though they piled broken furniture into the fireplace. Some accident would quite likely overtake them, or pneumonia might strike them down. They were like the highly bred spaniels and Pekinese who at the end of their leashes had once walked along the city streets. Milt and Ann, too, were city-dwellers, and when the city died, they would hardly survive without it. They would pay the penalty which in the history of the world, he knew, had always been inflicted upon organisms which specialized too highly. Milt and Ann — the owner of a jewelry store, a salesgirl for perfumes — they had specialized until they could no longer adapt to new conditions. They were almost at the other end of the scale from those Negroes in Arkansas who had so easily gone back to the primitive way of living on the land.

After recrossing the continent, Ish settles back in Berkeley, determined to make the best life that he can in the region that he knows so well. Before the first year is out, he crosses paths with Em, a woman still living in the city. They find each other congenial and agree to face the future together. (Em is an African American. It speaks well of George R. Stewart that he makes his hero and heroine an interracial couple, just as it says a lot about 1940’s America that he had to kill off the rest of the human race to do it.)

Eventually a small group of survivors coalesces around Ish and Em, and Ish becomes the community’s undisputed leader, spending his time trying to shepherd and shape this small society so that it may avoid the mistakes of the past. Ish uses his hammer to chisel a number for each year (beginning with the year one) into a large rock in a nearby park, and the community gives the year a name based on its most memorable event — “The Year of the Fires,” “The Year of the Twins,” “The Year when Joey Read,” and so on.

As time passes, children are born, and they in their turn have children of their own, and as the original group ages and dies, Ish finds himself the ancient and venerable leader of a tribe of superstitious and incurious strangers. (To his great discomfort, they come to see his hammer as an instrument of semi-divine power and authority; they grow so reverent towards the tool that they are reluctant even to touch it.) His ways are not their ways, because their world is not his world, and as the years go by and the electricity and water fail, the group more and more reverts to a pre-industrial way of life.

All through the book Ish is a careful observer of this embryonic society and even more of the eternal Earth that has always been his greatest fascination. The marks that men have made upon the land immediately begin to fade, because when the human race is subtracted from the equation, the effects of sun and wind and rain and snow quickly accumulate, causing bridges to collapse and roads to become impassible as people are no longer present to repair them. Likewise, there is no one to hold vegetation in check anymore, and plants begin the steady encroachment that will eventually efface all the works of man.

Ish notes wild fluctuations in animal and insect populations — at first he is inundated by successive waves of ants and later rats; with no human check upon their numbers, the creatures increase exponentially until they are everywhere. However, the situation soon stabilizes as these exploding populations outrun their food sources; the excess creatures die off almost overnight and nature recovers her balance. (Stuart implies that something like this was what happened to Homo Sapiens too, which are natural creatures subject to natural laws just as much as rodents are, though self-involved human beings tend to forget that.) Animals like sheep and cows, which had come to completely rely on human protection, vanish completely, while others like dogs easily revert to their wild and independent ways. (Stuart seems to think that dogs would do much better in a human-less environment than cats. I’m no naturalist, but I’d give him an argument on that one.)

These self-regulating changes and unhurried adjustments in a natural world that is quite unimpressed with mankind are the very heart of the book. They are often detailed in extended passages where Stuart departs from the story of Ish and his community and speaks with complete detachment, as if it is the ageless voice of history itself which is speaking. The effect of these sections — indeed, of the book as a whole — is to elicit a sense of quiet awe in the reader, the kind that occurs when we are privileged to be present at life’s most momentous events, occasions of birth and of death, those first and last things that stir us so deeply. On both the largest and smallest scales, Earth Abides is about precisely these fundamental things, and Stuart is profoundly concerned with how much influence we actually have over them and with how much we can truly control our lives and this world that we think we’ve mastered. His answer seems to be: not nearly as much as we like to believe.

Early on, Ish conducts a school for the children, attempting to teach them to read and write, and to pass on to them some rudiments of scientific and historical knowledge. But Ish finally gives up his educational scheme when his youngest son, Joey, the brightest and most curious of the younger generation, dies of typhoid fever, and Ish realizes that the other children simply aren’t interested in the learning that he is trying to impart to them, which they see as just one more irrelevant, useless relic left over from the “old time,” like all the other rusting and incomprehensible artifacts that surround them.

George R. Stewart

Ish even comes to accept that the university library, which he has carefully guarded, believing that its repository of knowledge will one day be used to recover all that was lost, will instead be forgotten, its contents moldering away into indecipherable piles of dust. He has some small successes — he teaches the tribe archery against the day when the rifles break down and the ammunition corrodes past the point of use, and he incites them to dig a well and to start growing some basic food crops. But there will be no revival of the old civilization; whatever comes next will have to create itself. By the time of his death at the end of the book, Ish is regarded both by the tribe and by himself as the Last American, the last man with any connection to the old times. (“Americans” are what the successors come to call the original survivors, those antique inhabitants of a fabulous, mythical world of strange customs and magical objects that can be neither understood nor recreated.)

At the last, worn out by a lifetime of (usually fruitlessly) trying to guide and preserve, Ish has ceased to care about what shape the future will take; having done his best to tend the fire, he is content to let the embers fade to ashes. The future is a mystery that those who come after will have to solve on their own, and the riddle is too complex for any one person to answer, even someone as resourceful and determined as Ish. He finally understands the smallness of human ambitions and the impermanence of human achievements and as “one who has studied the ways of the earth,” he knows that only one thing truly lasts. With his final thought, Ish, who has always been a rationalist and not a mystic, nevertheless still takes some comfort from the ancient words of the book of Ecclesiastes: “Men go and come, but the earth abides.”

If this great and powerful book has a flaw, it is a lack of human drama. That is a curious charge to make against a book which narrates nothing less than the abrupt end of human civilization due to a worldwide catastrophe, but it is true. Billions die, but Ish doesn’t directly experience that and neither do we; it all takes place as he lies feverish in his cabin, and when we emerge into the radically altered outside world, we only see the results through the unflappable Ish’s eyes.

Even when Ish is no longer on his own and the community (that source of all human strife) is established, there’s very little conflict there, as everyone readily accepts his leadership — the first and only challenge to it doesn’t happen until two thirds of the way through the story, and is dealt with quickly. (An uninvited and deeply dangerous new member of the group is put to death by the vote of Ish and the other senior members of the community, but the execution happens offstage. Stuart quickly jumps from the fatal vote to a scene which takes place after the interloper’s burial.) All of this results in a book with a surprisingly low emotional temperature, considering the enormity of the events it narrates. The book is very moving, but the emotions it stirs are more like slow and powerful ocean currents instead of excited but superficial splashings at the surface of a pond.

Which is, I’m sure, just as its author intended. Earth Abides, after all, is about the insignificance of all our works and ways. The elegiac, “all passion spent” mood of the book is perhaps the most memorable and affecting thing about it, and it perfectly fits Stuart’s wide-scale vision and quiet message of calm acceptance. One life, or a billion lives — they matter hugely to us, of course, but the inhabitants of a beehive likely think they’re the favorites of the universe, too.

In the vast life of the Earth itself, though, of what importance is all of our planning and striving, our myriad failures and successes, our restless hopes and fears and joys and sorrows? What do we matter to a world that was here long before we were and that will endure long after we are gone? Our best course is to understand and embrace our transitory part in the natural pattern, a part which can still be worthy in spite of — or perhaps even because of — its brevity.

Earth Abides does have drama, but it’s not the petty drama of dynastic politics or palace revolutions or personal revenge. Instead, its drama is of the enduring kind that’s inherent in a snowstorm or in the endless cycle of the seasons or in the awesome inevitability of the rise and fall of the tides. In our age of ever more frantic acceleration, ever more ceaseless motion, Earth Abides stands out greater even than when it was written, greater than ever, like a serene and silent mountain rising high above a chaotic and conflict-riven plain, honest and wise and beautiful and true.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a look at Ray Bradbury’s prophetic short story “The Murderer.”

Earth Abides used to be, I think, one of those novels of the future that were commended to the attention of people who had been inclined to dismiss science fiction as inherently subliterary.

I’ve read Storm, too — pretty impressive.

Excellent review of a classic novel which is largely unappreciated.

Thank you, sir – always nice to get an appreciative comment, even five years after you’ve written something!