Hither Came Conan: Bobby Derie – “The Phoenix on the Sword”

Our Hither Came Conan series gets well and truly underway this week with Bobby Derie presenting the case for “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Grab your loin cloth and tulwar (or zhaibar knife, if you prefer…) and tread upon some jeweled thrones!

Our Hither Came Conan series gets well and truly underway this week with Bobby Derie presenting the case for “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Grab your loin cloth and tulwar (or zhaibar knife, if you prefer…) and tread upon some jeweled thrones!

“Know, oh prince…”

The Texas pulpster sat at his typewriter, pounding away at the keys, talking the story out loud as he typed. The long novella of King Kull, “By This Axe I Rule!” written some years earlier remained unsold, rejected by Argosy and Adventure. Already the Texan was working over the history in his mind, weaving together bits of fact and legend of the “Age undreamed of.”

Thinking back to just months ago when he had been down south, in a dusty little border town of the Rio Grande valley, and a character had come into his mind…a raw conception with an old Celtic name, and…

“Hither came Conan, the Cimmerian, black-haired, sullen-eyed, sword in hand, a thief, a reaver, a slayer, with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.”

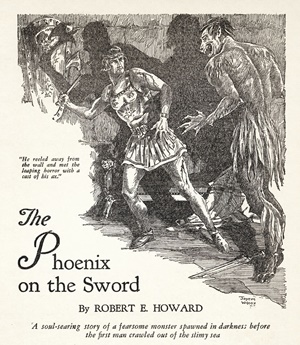

The opening to “The Phoenix on the Sword” is the greatest incipit in pulp fiction, an invocation to the muse of artificial mythology, a sketch of a world and a character all at once. It ran as the banner across the Marvel Conan comics for decades, and an abbreviated version opened the 1982 film which introduced the Cimmerian to a whole new audience. It almost didn’t happen.

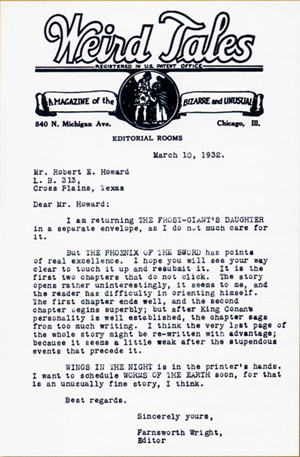

“But “The Phoenix on the Sword” has points of real excellence. I hope you will see your way clear to touch it up and resubmit it. It is the first two chapters that do not click. The story opens rather uninterestingly, it seems to me, and the reader has difficulty in orienting himself. The first chapter ends well, and the second chapter begins superbly; but after King Conan’s personality is well established, the chapter sags from too much writing.”

—Farnsworth Wright to Robert E. Howard, 10 Mar 1932

The story behind “The Phoenix on the Sword” is almost as interesting as the tale itself. It is the first adventure of Conan the Cimmerian, but that is just the part of it. Robert E. Howard sold his first story to Farnsworth Wright in 1924, and Weird Tales, and once he started selling regularly, remained a steady, if occasionally fickle, market. He had tried repeatedly at establishing a series character for the magazine, and sold stories of Kull of Atlantis and Bran Mak Morn. Both failed after a few episodes; Solomon Kane lasted longer, with seven adventures spaced out over four years. Then, in 1932…Conan.

Howard would write to Clark Ashton Smith that:

“Conan seemed suddenly to grow up in my mind without much labor on my part and immediately a stream of stories flowed off my pen”

But the truth is the character was the product of real toil. “By This Axe I Rule!” went through multiple drafts, all typed out by hand, and once re-written as “The Phoenix on the Sword” it went through the process again, not least because of Wright’s critical appraisal. While Howard sometimes posed as a spontaneous writer, the stories always represent real research on the Texan’s part, and the first rough gems always had to be polished by subsequent passes.

But the truth is the character was the product of real toil. “By This Axe I Rule!” went through multiple drafts, all typed out by hand, and once re-written as “The Phoenix on the Sword” it went through the process again, not least because of Wright’s critical appraisal. While Howard sometimes posed as a spontaneous writer, the stories always represent real research on the Texan’s part, and the first rough gems always had to be polished by subsequent passes.

“The Phoenix on the Sword” is not the surprise effort of an uneducated prodigy; it is the masterpiece of a journeyman that has served their time honing his craft, and now after seven years apprenticeship showcases their skills.

The result is an abbreviated epic, with bold language and characters with a hint of Shakespeare and the legends of Bulfinch’s Mythology to them. The five chapters are short, but the action moves briskly, plot building steadily. At every turn, readers are reminded that this is not quite the world they know, or any world they knew; the setting is painted in vivid colors; the final sentence to the opening chapter is worthy of the Thousand and One Nights: “Over the jeweled spires was rising a dawn crimson as blood.” Yet the setting extends beyond the immediate scenes: characters are from and headed to other places, concerned with events along the border, reminisce about pasts in far-off lands.

It is worldbuilding—the hint and suggestion of something bigger, more coherent, more realistic than the average pulp tale, and something which Howard had become proficient in after the last couple of years, dabbling in the Cthulhu Mythos with stories like “The Black Stone” and “The Thing on the Roof.”

The opening of each chapter begins with a snippet from the Nemedian Chronicles or the epic poem The Road of Kings, hinting through these pseudo-texts at a larger, more developed world (though in fact Howard would not write his seminal background essay, “The Hyborian Age,” until a couple more stories of Conan had been written and sold). Readers wrote in asking for the complete verses, and like H. P. Lovecraft and his artificial Mythos, Howard was forced to admit: “I was sorry to have to tell them that it didn’t exist.”

It is also one of the most quotable tales of the Conan canon. “Poets always hate those in power.” “I had prepared myself to take the crown, not to hold it.” “A great poet is greater than any king.” “They have no hope here or hereafter.” “Rush in and die, dogs—I was a man before I was a king.” “Who dies first?” “Slaying is cursed dry work.” The language is crisp, and at times poetic, yet often concise, pared down to essentials.

Howard is present in “The Phoenix in the Sword” in his own style, distinct yet equal to the best Weird Tales had to offer. Not the exotic prose poems of Clark Ashton Smith or the occasionally ultraviolet prose of H. P. Lovecraft. It communicates everything efficiently and quickly enough to please Farnsworth Wright, but never seems to rush; every scene takes its own pace, every character plays their part upon the stage, and then has their graceful exit when their bit is done.

Over the course of the story, “The Phoenix on the Sword” establishes many of the key elements of the canonical Conan: the character appears fully-formed, a cynical and brooding outsider who is yet determined and fair. His chief antagonists are a group of plotters to seize the throne by deceit and force of arms, a plot carried over from “By This Axe I Rule!,” and leading into the kind of hard-hitting action which Howard excelled at writing.

Yet this was a story for Weird Tales, not Argosy or Adventure, so Howard introduced a supernatural element in the form of the Stygian wizard Thoth-Amon, a character that has grown substantially greater in various adaptations and expansions of Howard’s work than he did in anything the Texan wrote…yet this would form only the first of many wizards he would face.

Yet this was a story for Weird Tales, not Argosy or Adventure, so Howard introduced a supernatural element in the form of the Stygian wizard Thoth-Amon, a character that has grown substantially greater in various adaptations and expansions of Howard’s work than he did in anything the Texan wrote…yet this would form only the first of many wizards he would face.

Though they do not face each other directly in this story, “The Phoenix on the Sword” is as much Thoth-Amon’s tale as Conan’s. His is a threat that builds up from a haunted slave and outlaw in the first chapter, to a supernatural threat and harbinger of the dark god Set in the fourth. Even Conan cannot defeat him directly, because he never faces Thoth-Amon; the best the Cimmerian can do is destroy his emissary, and that only with great courage, effort, and supernatural aid. Thoth-Amon is as victorious in this tale as Conan, and though they never meet directly in Howard’s work again, the Texan has set up two titans, distinct, opposite in character and nature, destined for a recurring conflict.

There are a lot of conflicts in “The Phoenix on the Sword.” Conan is at conflict with himself, an uncivilized barbarian and soldier who struggles at being a king and statesman; he is in conflict with his environment, where the people see him as a foreigner and interloper; he is in conflict with his fellow men, violently so in the final blood-soaked chapter; and at that climax… he enters an even greater conflict: confronted by Thoth-Amon’s sending, a demon.

Man versus the supernatural, sword against sorcery. The triumph of Conan in this tale is not only about one blood-soaked barbarian overcoming his foes—though that absolutely happens—it is about the Cimmerian resolving his other internal and external conflicts. The appearance and aid of Epemitreus is the tacit acceptance and acknowledgement of his kingship: “Your destiny is one with Aquilonia.”

That Conan who faced the ghostly sage is a mature man at his full powers—not a callow youth or thief, pirate or soldier-of-fortune. He is a “barbarian” to the civilized Aquilonians, in a theme that would be reiterated more strongly in later stories; yet what a “barbarian” King Conan is! He holds poets in such high regard that he would spare the life of a traitor during a battle, who idles his time by drawing in the missing borders of maps, and knows of sages that were dead fifteen hundred years. Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” is not the often-parodied musclebound brute.

That Conan who faced the ghostly sage is a mature man at his full powers—not a callow youth or thief, pirate or soldier-of-fortune. He is a “barbarian” to the civilized Aquilonians, in a theme that would be reiterated more strongly in later stories; yet what a “barbarian” King Conan is! He holds poets in such high regard that he would spare the life of a traitor during a battle, who idles his time by drawing in the missing borders of maps, and knows of sages that were dead fifteen hundred years. Conan in “The Phoenix on the Sword” is not the often-parodied musclebound brute.

“The Phoenix on the Sword” rewards repeat reading. Little moments and details stand out to catch the imagination; things said and left unsaid. When Thoth-Amon draws Ascalante’s slipper from his girdle, it hints at both the character of the wizard, to carry such a token of hoped-for revenge, and at the limitations of magic in the setting.

Sorcery in the world of Conan is not pure make-believe; it exists side-by-side with superstition, which suggests it is something relatively rare, and it follows its own obscure rules. The reader never gets knows fully how it works—a course on black magic was not Robert E. Howard’s aim—only that it is limited, and that makes it somehow more real. If sorcery did exist, if the old grimoires held any truths in our own world, would it not look like that? Wouldn’t a man as consumed by fear, hate, betrayal, and deceit as Thoth-Amon use it?

In many fantasy stories, there is a dream-like quality to it all. In the light of day, wide awake, the things that happened may seem foolish, or leave no trace behind. In “The Dunwich Horror,” Wilbur Whateley dies, and his remains dissolve without a trace; Dorothy wakes up after the events of The Wizard of Oz and it seems like all of it was just a dream; Ebenezer Scrooge taunts the Spirit that it is just “a bit of undigested beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potato.” The fantastic is left an open question, a hesitant possibility, easy to deny…but not in the Hyborian Age. Not in “The Phoenix on the Sword,” where the slain demon leaves a shadowy outline etched clearly in its own blood.

“Know, oh prince…” the pulpster says out loud in his Texas drawl, his voice probably echoing through the thin walls to where his mother lays. He wrote for the promise of a check, for badly-needed money that would put food on the table and medical treatment for his mother during the depths of the Great Depression. Yet many pulpsters wrote for a check, thousands of words a day, from places like New York City and Chicago where they could drop in and see the editors for lunch. Not many from rural Texas, where a man who chose to write for a living was an oddity. He would write to Lovecraft:

“I took up writing simply because it seemed to promise an easier mode of work, more money, and more freedom than any other job I’d tried. I wouldn’t write otherwise. If it was in my power to pen the grandest masterpiece the world has ever seen, I wouldn’t hit the first key, or dip the pen in the ink, unless I knew there was a chance for me to get some money out of it, or publicity that would lead to money.”

“Hither came Conan.” After Howard’s death, Lovecraft would write of his friend:

“Hither came Conan.” After Howard’s death, Lovecraft would write of his friend:

“It is hard to describe precisely what made his stories stand out so—but the real secret is that he was in every one of them, whether they were ostensibly commercial or not. He was greater than any profit-seeking policy he could adopt—for even when he outwardly made concessions to the mammon-guided editors & commercial critics he had an internal force & sincerity which broke through the surface & put the imprint of his personality on everything he wrote. Seldom or never did he set down a lifeless stock character or situation & leave it as such. Before he got through with it, it always took on some tinge of vitality & reality in spite of editorial orders—always drew something from his own experience & knowledge of life instead of from the herbarium of sterile & desiccated pulpish standbys.”

‘The Phoenix on the Sword” is more than just a potboiler. That, beyond any of its other attributes, is what stands out to me as why it is the best of the Conan canon. This was the story from a writer that wouldn’t quit, despite rejection after rejection; who would write his best when he could have written puerile pap and gotten the same money, as so many other pulp writers did. Who struggled to create a series character that would resonate with editors and readers alike. When Wright turned it down, he doubled down and rewrote it again; and this time, he succeeded. Whatever else a reader might experience of the favorite barbarian—the books, the movies, the comics, the pastiches and parodies and all the rest—it started here.

From the Dusty Scrolls (Editor comments)

The next two stories after “The Phoenix on the Sword” (“The Frost Giant’s Daughter” and “The God in the Bowl”) were rejected by Wright.

“By This Axe I Rule!” can be found in Del Rey’s Kull: Exile of Atlantis. It was first published in Lancer Books’ 1967, King Kull.

The “Know, oh Prince,…” opening to this story may be the most famous lines in the Conan Canon. And it’s the result of editorial input. As mentioned above, Wright told Howard that chapter two sagged “from too much writing.” That referred to about a thousand words in which Conan discussed the map of the Hyborian world with Prospero. Howard excised all that and inserted the prologue at the beginning ot the story. It was a brilliant move.

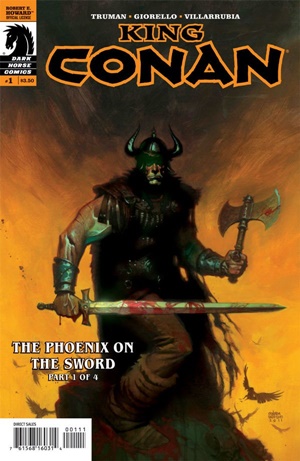

Roy Thomas adapted “Phoenix on the Sword” for 1976′ Conan the Barbarian: Annual #2 (Attack of the Midnight Monster!), from Marvel Comics. It was a 52 page annual. Most single issues were only 36 pages.

In 2012, Dark Horse Comics did a four-part adaptation of “The Phoenix on the Sword” as part of the King Conan line.

I had the order askew in last week’s post. I think I’ve got it right now. And we’ve added Woelf Dietrich’s look at Howard’s partially completed story, “Wolves Beyond the Border.” So next week, see what Fletcher Vredenburgh has to say about “Frost Giant’s Daughter.”

Prior Posts in the Series:

Here Comes Conan!

The Best Conan Story Written by REH Was…?

Up next week: Fellow Black Gater Fletcher Vredenburgh takes on “The Frost Giant’s Daughter.”

Bobby Derie is the author of the Collected Letters of Robert E. Howard – Index and Addenda (2015, Robert E. Howard Foundation Press) and Sex and the Cthulhu Mythos (2014, Hippocampus Press). He is a multiple Robert E. Howard Foundation Awards winner.

Bob Byrne’s ‘A (Black) Gat in the Hand’ was a regular Monday morning hardboiled pulp column from May through December, 2018.

His ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column ran every Monday morning at Black Gate from March, 2014 through March, 2017 (still making an occasional return appearance!).

He also organized Black Gate’s award-nominated ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series.

He is a member of the Praed Street Irregulars, founded www.SolarPons.com (the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’) and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

He has contributed stories to The MX Book of New Sherlock Holmes Stories – Parts III, IV, V and VI.

And he will be in the anthology of new Solar Pons stories coming this year.

This story appeared in the December 1932 issue of Weird Tales. Howard’s Worms of the Earth, esteemed by some as his single finest story, was in the November issue. His ferociously intense Solomon Kane yarn Wings in the Night showed up in July. And The Scarlet Citadel would appear hot on the heels of The Phoenix on the Sword, the very next month, January 1933.

No doubt REH was on a roll, but it’s this story that has the most glamour, that in retrospect casts the strongest spell.

I bought the December, 1932 issue of Weird Tales from Bob Weinberg back in the 80’s. It’s not in good shape, but that tattered old magazine paradoxically seems like a heavy cornerstone. A weighty block, unstained and enduring, in the foundation of a vast and irregular palace that has never stopped growing since. Nothing and no one can ever capture the essence and power of Howard’s original vision, but when you read this story you can understand why his Cimmerian stays in print and sounds so many echoes across cultures worldwide.

Bobby Derie had an easy one, of course; easy in that it’s hard to deny “The Phoenix on the Sword” is at least ONE of the greatest Conan stories, as well as being the first. But he does a good job with it, making his essay as much about the writing and publication of the story as he does the content, without skimping on the latter. He makes an especially good point about the tale being as much Thoth Amon’s as Conan’s, as well as exploring what I think is one of the main things that distinguishes Howard from many of his imitators–his are lived-in worlds, not just settings for whatever tale he happens to be telling. They have their own history, and contain other stories. One of the factors that makes Conan work so well is that the stories about him aren’t just his stories; in fact, more often than not, his author drops him into SOMEONE ELSE’S STORY, already full of plot, character and consequence, and his actions have real effects on events that would unfold in SOME fashion even without him. Conan’s is not a cardboard world where a monster gets slotted in just ahead of the hero’s arrival, in order to be slain. Rather, it’s been lurking there for ages, and the protagonist is very lucky to get out alive. And Bobby captures, I think, something of the excitement for its first readers of the story when new. It’s a great story, no question, and as he demonstrates, there’s a great story behind it as well.

And the insightful commentary beings. Awesome!!!

Let me bring the quality level down a bit…

I’ve been leafing through Dark Valley Days (both for future posts in the series and after my discussion with Brian).

I came across a de Camp comment on Thoth Amon being a major character in the “Conan Saga.”

That’s an interesting observation (one that I also believe asserts de Camp considers his pastiches as much a part of the Conan Canon as Howard’s originals – but I’m not looking to make that point here).

The ‘officialness’ of pastiches was the subject of an earlier post. One I made when I knew a lot less about Howard.

But, Thoth Amon is in the first Conan story. He’s also mentioned in the third story written. He’s not present, but he is a major part of the plot. So, you’ve got Thoth Amon featuring in two of the first three stories.

Then never mentioned again by Howard. The de Camp/Carter pastiches, and the Marvel comics, would make Thoth Amon the Moriarty of the Conan stories.

But Howard was done with him in that first flurry of Conan writing.

I find that interesting and something I’d like to try and learn more about. Why did Howard drop Thoth Amon so suddenly and definitively?

Bob: I don’t know that anyone has tried to do “A Probable Outline of Thoth-Amon’s Career,” but I think a large part of the reason he and Conan don’t intersect much is just that they were in different places for most of their lives – and Howard wasn’t writing Conan’s stories linearly, he was jumping around in time and place. Thoth-Amon would have probably spent most of his time in Stygia, whereas Conan was seldom near there (although that does beg the question: What was Thoth-Amon doing during the events of “The Hour of the Dragon?”)

greyirish – That’s true. And a couple of the Tor books have Thoth-Amon. Including Sean Moore’s Conan and the Grim Grey God, which, for the most part, I liked very much.

For me, it leaves me wondering what Thoth Amon did after he got his ring back (in Howard’s world).

There used to be this comic called “Bloom County” – one time Opus the Penguin wrote his biography which didn’t sell. His friend (and journalist, hoaxer, political canidate advisor, etc.) Michael Bloom suggested he sex it up for it lacked “Oomph” – so Opus got real insulted and briefly re-named it “Conquests of a Stud Monkey”. He then calmed down and let his friend re-write it, embellishing a little, to wild success and ego crushing embarrassment.

As I absorbed the tales, noting the similarities between Kull and Conan, especially that one, then noted the back-story I did think Conan was a simpler, more sexified version of Kull – set in a later era of the same world so he could go back to Kull if he felt like it without totally re-worldbuilding. I think I’ve heard some Howard fans say they like Kull, the few stories that exist, far better – but I like all Howard and even with the reality of Conan being a more marketable Kull which is likely true they still are wonderful stories and so tragic so few.

Kull was perfect for Weird Tales at its core – the eldritch horror, the Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith stuff. Conan was perfect for Weird Tales on its Covers – the stuff they had Mrs. Brundage do. So he achieved success with Conan.

IMO if Howard had lived there would have been major stories involving Thoth Amon and returns to Atlantis and Thulsa Doom vs Kull. The long running Marvel series seized on that to fill in the blanks “Show must go on/why/coz if it don’t we don’t get paid” style.

On the comics note it seems Marvel has the rights coz Dark Horse dropped them. IMO Dark Horse wimped out – they were increasingly dodging stuff that’d be “Politically Incorrect” by today’s standards and eventually would have to get to “Red Nails” and “Man Eaters of Zamboulla”. Too bad for the stuff they worked with especially at start was pure “Blood and Thunder” – I like especially “Black Colossus” From what I’ve glanced Marvel in in Savage Sword/Cash Grab mode though the writer Jason Aaron is pretty talented – such as his pre-flood series “The Goddamned” (short, started out awesome, likely cancelled due to abrupt ending) so it might grow into something better and re-starting the Conan tales so soon after Dark Horse did so well at start would be redundant and tedious.

Calvin and Hobbbes, Fox Trot, and…Bloom County are my three favorite strips.

I think, with the lack of supernatural and sorcery, the Kull story feels very different than the Conan one. It’s much more philosophical. Not fantastic at all. More like a fantastic historical..

I’m working on a bonus post, discussing the two stories. Just not finding much time to write it!

I know that Marvel is doing some original story stuff for future issues. Not just the REH tales.

They’re also releasing all the ‘Conan the Barbarian’ and ‘Savage Sword…’ originals in pricey Omnibus editions. Starting this month.

Its off to a great start! I had thought about posting a long comment about the differences between the two stories, but after reading this i don’t think thats what you’re going with here.

This is the story that tells a lot about Howard’s writing process. Because this is so early in the Conan mythos its difficult to tell what was put there to characterize Conan and what is left over from Kull.

It doesn’t seem very like Conan to spare a minstrel who is actively trying to kill him. Is that something that was put there to show a more mature Conan? or is it just left over?

What does seem intentional is that even here at the beginning, Conan is not quite as serious and melancholy as Kull. Here Prospero and Conan are telling stories and laughing a bit. You never see Kull/Brule doing that.

Even the parts with Thoth-Amon and the nobleman are kind of funny. Thoth tells his life story that includes a deadly ring, the noble not listening at all then pulls out the ring that Thoth was just ranting about.

I think if you take each story on its own then “Phoenix on the Sword” is better. But if you’ve read several Kull stories and end on “By This Axe I Rule” then I think it wins out. It really hits home about Kull’s frustrations with Valusian law and how angry he is when he smashes the tablets.

I haven’t been able to find anything that says if DH lost the license or gave it up.

I know I saw some interviews two years ago where Mike Richardson of DH had long term plans for Conan. I doubt they would have given it up if they had a choice/could afford it.

Glenn – any commentary is welcome. Despite how I presented the series, its not really “This is the best one.” With a vote at the end or anything.

It was to look at each story and find its strengths.

And any discussion related to the story – even primarily Howardian – is fine with me. And I’d like to see your thoughts.

If I can round up enough interested people, it is conceivable Black Gate could run another series in 2020 or 2021, discussing each Kull story.

I’ve already thought about a follow-up focusing on Solmon Kane.

I’m a much bigger fan of Kane than Kull, myself.

Sign me up for the Kane series!

Now we get to the meat of the series.

An excellent start. This article sums up what made The Phoenix on the Sword such a striking introduction to Conan and the Hyborian world. Clearly there was a bit of inspiration but mainly it was perspiration and graft that brought Conan to life.

That is one thing that has always irked me with the attitude of fans of so called ‘literary’ fantasy. That somehow S&S fiction required no effort to write; that no care was taken and could be replicated without difficulty. Clearly this is not the case. Perhaps if it was more widely known how much effort Howard put in on Conan and his other characters then the work would be looked on in a different light.

This first article makes a great start to that process.

Glenn – I doubt you’ll get the truth from Dark Horse.

Years back I asked why the difference between some Shirow releases, and no I don’t mean the “Girls wanna have fun” pages from Ghost in the Shell 1 but later installments of the series also omitted nudity scenes – got a claim that there never was any nudity in it at all – even when I’d seen the Japanese version… Now, I don’t have an email from 98 saved in a form I can get immediately so you’ll have to take my word for it. BUT – easy to get GITS 2 and see where the English version doesn’t have the two cute ladies on the yacht sunbathing topless but then they pop open and they are kind of ‘mecha’ for smaller AI units. If they’ve corrected this, I apologize, but it wasn’t that way last time I checked (2 weeks ago) at Barnes and Noble with the latest prints on the shelves…

I bet they abandoned the Conan license though, due to SJW convergence as Vox would have called it. Seemed to be longer and longer between eps with too much pointless filler stories. This is when it took off like a lion. Back eps on Amazon are still often near cover price. I know they were selling well, I had to pre-order or pay a collector’s price or wait for the TPB when they were going strong the first few years.

They had gradually been doing subtle cuts to the non-pc parts of the stories after those first few years. The real offender where I knew something was truly wrong was in “People of the Black Circle” where they cut out a whole chapter because the Dark sorcerer used his magic on the princess to subdue her. Something even the code shackled and magazine savage sword handled pretty well. And no way did they cut that over length. Marvel did it comics with 2 issues, Savage sword in one – less than 1/5, or 1/2 the pages given to adapt.

Oh, and to Bob – I cut 2/3 what I typed before posting here – Coz I went on PC/SJW issues -and for “Fun” (Sarcasm) checked out Dark Horse’s site and sure enough full of “Woke” comics I can’t believe anyone would buy. But what I did type here relates to Dark Horse and -check their website I think it does argue my “SJW converged/dropped for that reason” argument.

Green – I figure, maybe it was just that Marvel wanted back in. And they’re big enough to get back in if they want to. They’ve got more weight now than they did back when it was just comic books.

I know they’re going to take a John Hocking unpublished novella and make it a series graphic novel. That was on FB.

And I’m pretty sure I saw Chris Oden post that he’s writing a story for another GN. I don’t know if it’s a single issue or also a series. Of course, I could ask him….

V.R. – The same principle seemed to apply to the pulps of the period. While some of it was dross, folks like Raoul Whitfield, Erle Stanley Gardner, W.T. Ballard, Frederick Nebel, George Harmon Coxe, et al (and of course, Hammett and Chandler) were producing quality fiction.

And it was dismissed as lightweight, unimportant, wordage. Not worth serious consideration. Just cranked out and not of merit.

And that was, simply, WRONG!

Same with some swords and sorcery.

> I bought the December, 1932 issue of Weird Tales from Bob Weinberg back in the 80’s.

John,

Another fascinating thing we have in common… I bought my first pulps from Bob Weinberg in the late 80s (or very possibly the early 90s) as well. I forget how we got introduced, but I drove over to his house and ended up buying a few issues of Astounding from him in his garage. I never saw his near-mythical pulp collection… maybe I’ll finally get the chance when it’s auctioned off at Windy City Pulp & Paper in April this year.

The obvious argument for today’s story occurred to me as I’ve been reading C.L. Moore’s Jirel of Joiry and Northwest Smith stories: the first story is the one good enough to get the editor and the fans clamoring for more, making the rest possible. (Black God’s Kiss is undoubtedly the best Jirel story, although she ends on one heck of a high note with Hellsgarde, and I have a hard time believing ANY story is better than Shambleau). Wright may have dinged a couple, but Conan had a strong enough start to survive some weak stories (basically the back half of the first Del Rey volume).

John – Pulp Hero Press is going to be reissuing Weinberg’s history of Weird Tales. I think expanded, as well.

I’m gonna get a copy!

With reference to the comment of V. Russell Waciuk, about “the attitude of fans of so called ‘literary’ fantasy. That somehow S&S fiction required no effort to write.”

How would anyone know about the effort that a given story, let along a given genre of stories, took to write? By what means would someone be able to gauge the inner state of another person so as to be able confidently to make statements about his or her expenditure of “effort”?

To answer my own question:

(1) One might look to whatever the authors were on record as saying about the effort required. Now here, we have statements by REH about how the character of Conan seemed to take over with him and he just had to write it down, etc.

It might be that that kind of remark has gotten around, and people less admiring of Howard’s work than others have seen it as legitimate evidence that it didn’t take a lot of effort for REH to write the stories. If they like Tolkien’s work, they might be aware also that he started writing The Lord of the Rings in Dec. 1937, and was still working on it at the end of the 1940s; it took enormous labor indeed.

(2) People might also make inferences from their own experiences as writers. I wonder if everyone here over 50 years of age had a youthful phase when he or she wrote sword-and-sorcery stories. I know I did. My barbarian was named Koroth, and he swung his sword in “Armor from the Crypt,” etc. And it WAS, in fact, pretty easy to write these stories. To write science fiction stories, one likely needed to know something about science; to write detective stories, one needed to know something about how the world works that one might not know at age 14 — and so on. But a sword-and-sorcery world was easy to concoct. It was fun making up a map for Koroth’s world and letting myself be influenced by things I had read, just as Howard, at a higher level of accomplishment of course, was influenced by his ready of Mundy, Burroughs, Dunsany, & the like.

This leaves the critical issue, though, pretty much where it was, which I think the posting and the first couple of comments in particular tried to tackle. Teachers who include “effort” in their assigning of grades might be doing the right thing (or might not — again, HOW, really can they know?); but the effort something took is a different matter from the quality and value of the product.

To Major Wooton – remember its always about “The Story”

I thought the rule was:

1 – virgins write the best sex scenes

2 – soldiers write terrible – meaning non-sellable war stories

3 – what works in science fiction what works in RL as far as at least technology – as any science teacher is usually healthily skeptical of Star Trek and foaming angry at Star Wars…

Just as I’ve said with apologies to Poul Anderson, Gnorts the Barbarian could make a mighty battle with a 50lb wet noodle and there’d be comics, a movie by a foreign bodybuilder and endless spin-offs if the writer is good and tells an entertaining story that touches enough people somehow.

Now I’m not into the “Detective” thing – but there was this book that got Paladin Press shut down – “Hitman: A guide for independent operators”. Like 30 years before the Darknet, the internet whatever – someone ordered the crazy stuff they published and instead of just drilling into a steel pipe packed with gunpowder (anarchist cookbook) they became “Hitmen” using said book to act as a guide on how to do it… Well big freak out when it happened, and for the ‘guide’ to be worth it the cops couldn’t have done better by following a bloody trail – it turned out the ‘author’ was a housewife. Her experience? She watched a lot of Soap Operas and when on tv James Bond films…

So she knew ZILCH about being a hitman. But wrote about it. And the book sold. And was convincing enough someone used for real…

Likewise “I’m not a Doctor but I play one on TV…” – that actually worked to shill products even as totally anti-logical it should help in any way to endorse or have said endorsement be helpful.

For me, what made this story different from almost every other Conan story was the poetry. Chapters 2,3,4 and 5 all start with verses taken from the epic poem The Road of Kings or Mithraen scripture and one that is part of Thoth-Amon’s demon summoning spell.

Read them out loud to yourself (alone if you have to); I think that they distill the essence of Conan and his world better than just about anything else written in so many words or less. The last four lines especially:

“What do I know of cultured ways, the gilt, the craft, the lie?

I, who was born in a naked land and bred in the open sky.

The subtle tongue, the sophist guile, they fail when the broadswords sing;

Rush in and die, dogs–I was a man before I was a king!

Mr. Byrne,

Thoroughly off-topic, but I would like to mention that Berke Breathed is publishing “Bloom County” again, through his Facebook account (alas!)

Hi Eugene – Yes, I follow him on FB. I wasn’t as crazy about Outland. And politically, he and I are pretty far apart. But I still think the guy’s satire and humor are absolutely brilliant. I have all of the Bloom County collections.