Clockwork Angels III. Hope is What Remains to be Seen

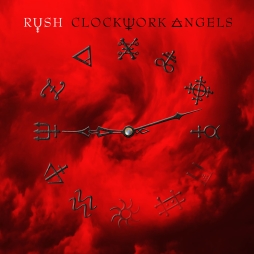

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the British North America Act came into effect, which effectively established the modern country of Canada. We still celebrate that as our national holiday: Canada Day. So it’s only appropriate that I’m posting now about three men who have together been named as official Ambassadors of Music by the Canadian government, who have been made Officers of the Order of Canada, and who have as a group won the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. I’m talking about Rush, and after two posts recapping their career (the first here, the second here), I’ll finally be writing about their new album, Clockwork Angels.

Today, July 1, is the one-hundred-and-forty-fifth anniversary of the date the British North America Act came into effect, which effectively established the modern country of Canada. We still celebrate that as our national holiday: Canada Day. So it’s only appropriate that I’m posting now about three men who have together been named as official Ambassadors of Music by the Canadian government, who have been made Officers of the Order of Canada, and who have as a group won the Governor General’s Performing Arts Award. I’m talking about Rush, and after two posts recapping their career (the first here, the second here), I’ll finally be writing about their new album, Clockwork Angels.

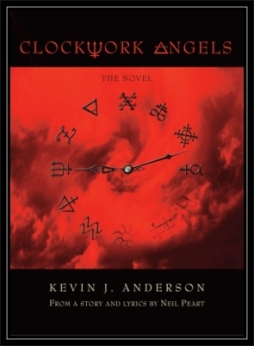

It’s a long album, over 66 minutes, and tells a single story. Although reminiscent of some of their older songs, not least due to lyricist Neil Peart’s use of themes and images that’ve clearly fascinated him for years, it’s also new ground for the band, who have never before created a fully-fledged concept album. Clockwork Angels is a steampunk epic in 12 songs, with accompanying passages of narrative prose that help to tie the story together. A novelization’s forthcoming in September by author Kevin J. Anderson, in collaboration with Peart.

To reiterate something I said in the first of these posts: this is a brilliant album. It’s lyrically and musically complex, constantly challenging, a treasure trove of ideas that’s impossible to assimilate in a single listen. The conceptual and narrative structure works, and lends the album a distinct feel — literally, a novelistic (and novel) sensibility. The relation of the songs, the recurrence of symbols that both resonate with the album’s story and derive from earlier in Peart’s career, gives Clockwork Angels significant thematic depth.

The story’s clear enough from the album and liner notes, but obviously the novel will expand on the tale considerably. A description of an excerpt of the novel can be found on the web, and Peart’s mentioned some story twists in interviews. I’ll assume this information can be trusted; if so, we know the name of the main character: Owen Hardy. The album follows Hardy’s eventful life, in an alternate world ruled by a mysterious Watchmaker.

The story’s clear enough from the album and liner notes, but obviously the novel will expand on the tale considerably. A description of an excerpt of the novel can be found on the web, and Peart’s mentioned some story twists in interviews. I’ll assume this information can be trusted; if so, we know the name of the main character: Owen Hardy. The album follows Hardy’s eventful life, in an alternate world ruled by a mysterious Watchmaker.

The opening song, “Caravan,” begins with a young Hardy hopping a train near his home, the small town of Barrel Harbor. He’s setting out to find his future, as young men do in Neil Peart songs. The details from the novel that’ve emerged so far come from this part of the album, providing a bit more background on Hardy and why his act of rebellion and escape is so significant.

The next song, “BU2B,” short for Brought Up to Believe, gives some background on Hardy and the world of the album. The Watchmaker rules from Crown City through enforcers called Regulators. Alchemist-priests have created coldfire that provides light and power — we already know from the first song that this is “a world lit only by fire” (while ‘coldfire’ recalls “Cold Fire” from the Counterparts album, a song broadly about emotional coldness and love burning away). More than that, Hardy’s been taught that this is the best of all possible worlds, a phrase from Voltaire’s philosophical satire Candide, which will be mentioned in the liner notes later in the album; this being a science fiction album, the residents of the Watchmaker’s world are aware of other parallel worlds, and seem to have some limited ability to at least observe those alternate timelines. For the moment, Hardy reflects on the faith he’s been taught: Believe in the best, and believe that “our loving Watchmaker / Loves us all to death.”

The next song, the title track, sees Hardy arrive at Chronos Square, in the heart of Crown City. He’s stunned by the glory of the city, the Timekeepers’ Cathedral and the Clockwork Angels of Land, Sea, Sky, and Fire. Hardy ponders the perfect obedience the Watchmaker demands: “Lean not upon your own understanding.” But then something happens; somewhere in Crown City Hardy meets a wandering pedlar. The encounter’s briefly audible on the CD, as the pedlar calls out the traditional pedlar’s cry: “What do you lack?”

The next song, the title track, sees Hardy arrive at Chronos Square, in the heart of Crown City. He’s stunned by the glory of the city, the Timekeepers’ Cathedral and the Clockwork Angels of Land, Sea, Sky, and Fire. Hardy ponders the perfect obedience the Watchmaker demands: “Lean not upon your own understanding.” But then something happens; somewhere in Crown City Hardy meets a wandering pedlar. The encounter’s briefly audible on the CD, as the pedlar calls out the traditional pedlar’s cry: “What do you lack?”

Rather than provide Hardy’s answer, we cut to another character for the next song: “The Anarchist.” Peart’s using a typical steampunk trope here, not commenting on modern politics; still, while thematically the song works perfectly, the associations with contemporary anarchy’s potentially distracting. At any rate, the Anarchist hears the Pedlar’s call and answers to himself that he wants vengeance. Excluded from the crowd, denied happiness and riches (“diamonds,” a common Peartian image), the Anarchist wants his revenge on the Watchmaker’s society, which he sees only through “The lenses inside of me that paint the world black / The pools of poison, the scarlet mist, that spill over into rage.” The first line seems to glance back to Grace Under Pressure’s song “Red Lenses” and perhaps to Presto’s “War Paint,” which tells its young protagonists to “Paint the mirror black.” The second line seems to be a reference to the album cover, which shows the hands of a clock, with symbols in place of numbers, floating above a red and black mist.

The key lyric here, I suspect, is a reference the Anarchist makes to “A missing part of me that grows around me like a cage.” We’ll see, in a picture accompanying the next song (at left; the symbol on the back of the upper hand is the symbol the album associates with the Anarchist), his hand reaching out above Owen’s hand; the two hands are near-perfect mirror images compositionally. He’s a kind of shadow to Owen: Owen’s counterpart.

The key lyric here, I suspect, is a reference the Anarchist makes to “A missing part of me that grows around me like a cage.” We’ll see, in a picture accompanying the next song (at left; the symbol on the back of the upper hand is the symbol the album associates with the Anarchist), his hand reaching out above Owen’s hand; the two hands are near-perfect mirror images compositionally. He’s a kind of shadow to Owen: Owen’s counterpart.

Owen himself has found work with a carnival, as we’re told in the next song, “Carnies.” A Midsummer Festival comes (and since winter hits later in the album, it’s tempting to see the story as being divided into seasons, a metaphorical year), and the carnival establishes itself in Chronos Square, complete with “a wheel of fate, a game of chance.” The Anarchist arrives at the height of the celebration, and disaster nearly strikes. Owen’s mistaken for the criminal Anarchist, and, disgraced, sets out for the sea.

Before he gets there, though, Owen has or recalls a love affair with a trapeze artist, a relationship he acknowledges now was always a bad idea, a product of illusion. Peart’s mentioned that a lifetime of reading went into the writing of the album, mentioning Voltaire, John Barth, Michael Ondaatje, Cormac McCarthy, and Robertson Davies, among others; I have to wonder, given a steampunk story about a female acrobat “with wings on her heels” who becomes the focus of a confused young man’s misplaced love, whether he’s glancing at Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus.

Before he gets there, though, Owen has or recalls a love affair with a trapeze artist, a relationship he acknowledges now was always a bad idea, a product of illusion. Peart’s mentioned that a lifetime of reading went into the writing of the album, mentioning Voltaire, John Barth, Michael Ondaatje, Cormac McCarthy, and Robertson Davies, among others; I have to wonder, given a steampunk story about a female acrobat “with wings on her heels” who becomes the focus of a confused young man’s misplaced love, whether he’s glancing at Angela Carter’s Nights at the Circus.

At any rate, the next song has Owen reach the sea, and set out for a mysterious western continent, where he searches for a legend: the “Seven Cities of Gold.” Even before finding Peart’s mention of Cormac McCarthy in connection with this song, I was thinking of McCarthy when I came across lyrics like “A man can lose his past, in a country like this.” Hardy wanders, seeking the cities, not finding them, drifting northward; then winter comes. What happens? The implication seems to be that he finds nothing, but the song ends with a glimpse of possible promise: “That gleam in the distance could be heaven’s gate / A long-awaited treasure at the end of my cruel fate.”

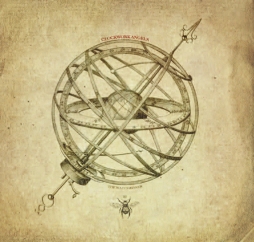

A couple points are worth considering here. Each song on the album has an alchemical symbol beside its lyrics in the liner notes; each symbol is one of the ‘numbers’ on the clock-face on the album cover. Each of the songs is in order on the clock-face — the one corresponding to “Caravan” first, then “BU2B,” then “Clockwork Angels.” But then comes the symbol for “The Pedlar,” the interstitial ‘song’ that isn’t a track on the album. To make room for the Pedlar, something else has to be dropped; the song that doesn’t appear on the clock face is “Seven Cities of Gold” (Peart has said that the symbol at 6 o’clock is supposed to be gold, representing this song, but traditionally the symbol that appears there represents the sun, which would fit with “Halo Effect.” The following speculation is even more likely than usual to be off-beam). I look at it this way: the Seven Cities are a legend that drives Owen, a dream from his youth. In searching for them he’s searching for transcendence, for precisely what is beyond clock time. Hence, it doesn’t appear on the clock.

A couple points are worth considering here. Each song on the album has an alchemical symbol beside its lyrics in the liner notes; each symbol is one of the ‘numbers’ on the clock-face on the album cover. Each of the songs is in order on the clock-face — the one corresponding to “Caravan” first, then “BU2B,” then “Clockwork Angels.” But then comes the symbol for “The Pedlar,” the interstitial ‘song’ that isn’t a track on the album. To make room for the Pedlar, something else has to be dropped; the song that doesn’t appear on the clock face is “Seven Cities of Gold” (Peart has said that the symbol at 6 o’clock is supposed to be gold, representing this song, but traditionally the symbol that appears there represents the sun, which would fit with “Halo Effect.” The following speculation is even more likely than usual to be off-beam). I look at it this way: the Seven Cities are a legend that drives Owen, a dream from his youth. In searching for them he’s searching for transcendence, for precisely what is beyond clock time. Hence, it doesn’t appear on the clock.

(Incidentally, the hands on the clock point to 9:12. Which, in 24-hour time, is 21:12. That’s the first of two temporal references to 2112 on Clockwork Angels.)

Another thought about “Seven Cities” which may or may not pan out in the novelization: as the song goes on, winter hits. “The nights grow longer, the farther I go / Wake to aching cold, and a deep Sahara of snow.” Now, Peart’s written another famous song about a wanderer seeking a legend through a frozen wasteland. There’s a sense, then, that “Seven Cities” is a direct parallel to “Xanadu.” But … the hero of “Xanadu” wandered “eastern lands.” Owen’s crossed into the Americas, which fits — the Seven Cities of Gold were a legend created by Europeans as they explored and exploited America. But he seems to be travelling northward, to judge by his references to lengthening nights and winter. Which I would dearly love to think means Owen finds his way through a wasteland of snow … to Canada. To Toronto, which in our world is at the heart of a region called the Golden Horseshoe. That’d make the song the exact inversion of “Xanadu,” with the wanderer seeking legend not in any mysterious foreign land, but among the mysteries of Peart’s own home town.

At any rate, whatever happens to Owen, he makes his way back to sea, and takes ship. But there’s a terrible disaster, caused by “The Wreckers” — residents of a sea coast who set up a false beacon, luring ships onto rocks so that they can scavenge whatever goods survive being wrecked on the shore. It’s a venerable folk-song trope based on true events, and here makes for a profoundly touching piece of music. The experience is devastating to Owen, the sole survivor of the ship; his faith in people is shattered. There’s a tremendously affecting darkness to this song, a mournful acknowledgement of the real damage people do to each other.

At any rate, whatever happens to Owen, he makes his way back to sea, and takes ship. But there’s a terrible disaster, caused by “The Wreckers” — residents of a sea coast who set up a false beacon, luring ships onto rocks so that they can scavenge whatever goods survive being wrecked on the shore. It’s a venerable folk-song trope based on true events, and here makes for a profoundly touching piece of music. The experience is devastating to Owen, the sole survivor of the ship; his faith in people is shattered. There’s a tremendously affecting darkness to this song, a mournful acknowledgement of the real damage people do to each other.

The next song, “Headlong Flight,” catches up to Owen some time later; if the album’s a musical, this is the beginning of the final act, possibly years after the dramatic events of “The Wreckers.” Owen’s had a full life, and now looks back through his memories, telling tales. He’s spent time as captain of an airship, recalling aerial journeys in other Peart lyrics, stretching back past “Presto” to the very first song Peart ever wrote for the band, “Fly By Night.” There’s also a touching nod in the liner notes here to “one of our great alchemists, Friedrich Gruber,” a reference to Peart’s drumming coach Freddie Gruber, who passed away late last year. At any rate, thinking over his memories, Owen seems to believe he’s come to terms with his past; but then the Pedlar returns again, with his eternal question, “What do you lack?” This triggers a crisis in Owen, and a reprise of “BU2B” — the haunting “BU2B2.”

“No philosophy consoles me / In a clockwork universe,” Owen says, but concludes “I still choose to live / And give, even while I grieve / Though the balance tilts against me / I was brought up to believe.” This is classic Peart, taking the concept of belief and twisting it around: belief not in God against all evidence, but belief in human goodness and human worth, against just about as much evidence. It’s touching, clever, and affecting.

“No philosophy consoles me / In a clockwork universe,” Owen says, but concludes “I still choose to live / And give, even while I grieve / Though the balance tilts against me / I was brought up to believe.” This is classic Peart, taking the concept of belief and twisting it around: belief not in God against all evidence, but belief in human goodness and human worth, against just about as much evidence. It’s touching, clever, and affecting.

Owen accepts the many disasters that have come to him. His response, now, to all the villains in his life comes in the next song: it is merely to “Wish Them Well.” A direct, simple rock song, it boils down to a simple piece of advice: “Let the demons dwell / Just wish them well.” One can’t help but recall here that demons are only fallen angels. Owen is putting his angels behind him.

The last song on the album is a deliberate recollection of Candide, “The Garden.” Candide, a naïf at the beginning of Voltaire’s book, settles down at the end to tend his garden. So Owen. “The Watchmaker tends to his schemes,” but Owen has “A garden to nurture and protect.” As in Voltaire, there may be a subversion of Christian imagery in putting the garden at the end of the story and not the beginning: the garden is not the utopia from which we are exiled, but the consolation we come to if we are wise enough to accept it.

(I have to admit I had some difficulty in parsing the continuity of the last four songs, starting with “Headlong Flight.” Neither the lyrics nor the prose notes have much to say about Owen’s external situation. Even more than most of the other songs, these are purely about his emotional state. I’ve described them how I interpret them. But I am pretty sure that they form a unit. If you add up the running times of those four songs, you come to a total of — what else? — twenty-one minutes and twelve seconds.)

(I have to admit I had some difficulty in parsing the continuity of the last four songs, starting with “Headlong Flight.” Neither the lyrics nor the prose notes have much to say about Owen’s external situation. Even more than most of the other songs, these are purely about his emotional state. I’ve described them how I interpret them. But I am pretty sure that they form a unit. If you add up the running times of those four songs, you come to a total of — what else? — twenty-one minutes and twelve seconds.)

So that’s the story of Clockwork Angels. It’s a strong story, I think, that avoids easy resolutions or simple heroism. It incorporates many of Peart’s favourite themes and images. In fact, looking over the evocations in his earlier lyrics of machines, wheels, angels, and the like, it seems almost inevitable. The steampunk genre lends itself to his concerns.

The image of the Watchmaker is a perfect example of what I mean. It obviously speaks to Peart’s profession as a drummer, keeping time for the band; and it speaks to one of his favourite themes, time and its passing. The image of the Watchmaker as the head of a religion goes beyond that. It of course recalls the Temples of Syrinx from “2112,” just as the Watchmaker’s ordered world recalls the Priests’ regulated mediocrity. But more than that, it recalls the famous teleological argument for God’s existence — essentially that the complexity of the world is analogous to the complexity of a watch, which couldn’t come into existence by chance but had to be put together by a conscious artisan. It’s a potent image, used and critiqued by any number of people over the past two or three hundred years, up to Alan Moore and Richard Dawkins. Peart’s the first one I know to fuse the image of the watchmaker with a steampunk setting. He’s alive to the full implications of the metaphor, as well; the suggestion of the world as a mechanism, an ordered and regulated place.

Owen in one way, and the Anarchist in another, represent challenges to this order. And the wandering Pedlar, who seems to spur them both on? In fact, according to Peart himself, one of the secrets of the album is that the Pedlar is actually the Watchmaker. His cry of “What do you lack?” is meant to elicit the answer “Nothing” from his perpetually-contented people. But Owen, the dreamer, is not satisfied with his clockwork life. He’s outside the Watchmaker’s plans.

Owen in one way, and the Anarchist in another, represent challenges to this order. And the wandering Pedlar, who seems to spur them both on? In fact, according to Peart himself, one of the secrets of the album is that the Pedlar is actually the Watchmaker. His cry of “What do you lack?” is meant to elicit the answer “Nothing” from his perpetually-contented people. But Owen, the dreamer, is not satisfied with his clockwork life. He’s outside the Watchmaker’s plans.

At the same time, Peart’s use of a period text to help structure his narrative gives his use of steampunk an unexpected but precisely appropriate twist. Voltaire wrote Candide after a series of disasters across Europe, most notably an earthquake that struck Lisbon in 1755. The great amount of death and destruction caused by the earthquake led many in Europe to question their faith. In Candide Voltaire mocked the easy assurance that we live in “the best of all possible worlds.” Peart’s extrapolation of that phrase to the science-fictional notion of infinite parallel worlds is clever; but his debt to Voltaire doesn’t stop there. Candide follows its hero through ruinous love affairs, and to North America; at the heart of the book, as of the album, is a search for the Seven Cities of Gold. It’s an unusual text to use for the inspiration for a steampunk bildungsroman, but it works.

So Peart uses steampunk, and adds to the genre in using it. I’m eager to see the novel; the album strikes me as a major work of dramatic science fiction, albeit in an uncommon form. It seems to me to be the sort of thing that ought to draw attention, and possibly awards, from genre watchers.

But as a Rush fan of long standing, even more striking than the steampunk elements is the structure. The closer I look at it, the more I notice similarities to “The Fountain of Lamneth” — Peart’s first side-long epic, perhaps his first extensive lyrical statement. The story of Owen Hardy has some strong parallels with that early tale; it’s richer, deeper, more accomplished, the work of a mature man rather than a youth in his early 20s, but obviously similar.

But as a Rush fan of long standing, even more striking than the steampunk elements is the structure. The closer I look at it, the more I notice similarities to “The Fountain of Lamneth” — Peart’s first side-long epic, perhaps his first extensive lyrical statement. The story of Owen Hardy has some strong parallels with that early tale; it’s richer, deeper, more accomplished, the work of a mature man rather than a youth in his early 20s, but obviously similar.

Both stories begin with the hero’s youth; both have him dissatisfied with the easy, contented life around him, and both see him pulled on by his dreams (“In the Valley,” “Caravan”) through a conflict with the morality he’s been taught (“Didacts and Narpets,” “BU2B”). Clockwork Angels is able to follow Owen’s story in more detail than “The Fountain of Lamneth” is able to track its protagonist. But both find their hero at sea, and then shipwrecked (“No One At the Bridge,” “The Wreckers”). “The Fountain of Lamneth” then has its hero fall in love (“Panacea”), where Clockwork Angels saw Owen fall in love before going to sea (“Halo Effect”). Interestingly, the hero of “Lamneth” leaves the woman despite what seems to be real love; Clockwork Angels, perhaps more knowingly and certainly harbouring fewer illusions, has Owen realise his love was fundamentally misguided.

At any rate, both characters end up older, wiser, sadder, and lost in their memories (“Bacchus Plateau,” “Headlong Flight” — and in the latter case the title suggests the escapism of the memories, a flight into the head). Clockwork Angels provides a real moment of crisis for the character, prompting his movement to, if not an epiphany as in “The Fountain,” at least the acceptance of “The Garden.” It’s a richer conclusion, more honest and more satisfying. It feels like something truly lived, and truly imaginable.

At any rate, both characters end up older, wiser, sadder, and lost in their memories (“Bacchus Plateau,” “Headlong Flight” — and in the latter case the title suggests the escapism of the memories, a flight into the head). Clockwork Angels provides a real moment of crisis for the character, prompting his movement to, if not an epiphany as in “The Fountain,” at least the acceptance of “The Garden.” It’s a richer conclusion, more honest and more satisfying. It feels like something truly lived, and truly imaginable.

The setting of the world, and the theme of the individual in conflict with society, certainly recalls “2112.” And I suppose you could argue for similarities to “Hemispheres”: the Apollonian world of the Watchmaker, the Dionysiac world of the carnival, the hero’s dramatic flight, the final achievement of balance (if on a personal rather than societal scale). But as I say, the story’s full of ideas that recur in Peart’s writing. The power of journey and travel. The difficulty of communication between people, and of being sure of what we see in another person. The double. The wheel of time and the wheel of chance. Magic and rationality.

Here as elsewhere, Peart plays with the distinction between transcendence and escape. If the world is basically materialistic, what need is there for dreams? But dreams are a primary need, that’s clear, and a primary drive to action. That apparent paradox fascinates Peart, who typically resolves it through art: it is art that defines us, art that our dreams create. The world of the Watchmaker is defective in art, over-rigorous in its rules. The garden Owen creates is looser, more natural. The garden is one’s life, we’re told; it is what we make.

Here as elsewhere, Peart plays with the distinction between transcendence and escape. If the world is basically materialistic, what need is there for dreams? But dreams are a primary need, that’s clear, and a primary drive to action. That apparent paradox fascinates Peart, who typically resolves it through art: it is art that defines us, art that our dreams create. The world of the Watchmaker is defective in art, over-rigorous in its rules. The garden Owen creates is looser, more natural. The garden is one’s life, we’re told; it is what we make.

Clockwork Angels is a success as music, and a success as a story. I’m anxious to read the full novel. But at the same time, there are joys here that are distinct to the form of the CD. It’s a summary and extension of Peart’s favourite motifs; one of those works in which an artist seems to encompass every part of their past work, transforming them and re-integrating them in a new way. Peart and his bandmates continue to push themselves, to find new ideas and new forms. But they also manage the balancing act of creating new work that’s informed by their history. There’s no-one like this group. “All I know is that sometimes you have to be wary / Of a miracle too good to be true,” Peart warns us in “The Wreckers,” but in the very last line of the album he allows “Hope is what remains to be seen.” I don’t know whether this is the best of all possible worlds. But there’s something to be said for it if, in its interplay of history and chance, it has produced this improbable virtuosic trio, and their near-four-decade-long success story.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] it that day. In reading what follows (the first of three posts, with part two here, and part three here), understand that I’m a fan, and that this has been my favourite rock group for over two decades. […]

[…] Clockwork-angels-iii-hope-is-what-remains-to-be-seen […]