Clockwork Angels II. Winding Like an Ancient River the Time is Now Again

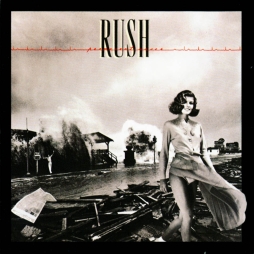

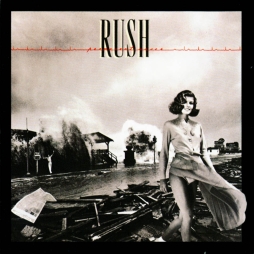

This is the second part of a look at Rush, whose new steampunk epic Clockwork Angels came out earlier this month. I think it’s a wonderful album, but to explain why it seemed to me worth looking at their earlier work — I looked at what they’ve accomplished as a band, and what drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has become as a writer. Last time, I looked at their records up through 1978’s Hemispheres; I therefore begin here in 1980, with the next album, Permanent Waves. (You can find that first post here; the third post, looking closely at the new album, is here.)

This is the second part of a look at Rush, whose new steampunk epic Clockwork Angels came out earlier this month. I think it’s a wonderful album, but to explain why it seemed to me worth looking at their earlier work — I looked at what they’ve accomplished as a band, and what drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has become as a writer. Last time, I looked at their records up through 1978’s Hemispheres; I therefore begin here in 1980, with the next album, Permanent Waves. (You can find that first post here; the third post, looking closely at the new album, is here.)

Permanent Waves began a process of moving away from the extensive side-long epics of past albums toward more concise songs. In this the band may have been influenced by the contemporary music scene — the title of the album, in addition to being a reference to the last song of the album, also glances at New Wave. Peart originally planned a long song based on the medieval poem Sir Gawaine and the Green Knight, but at some point plans changed. The lyrics were scrapped, and the music adapted for what became the record’s longest song, “Natural Science.”

“Natural Science” is a three-part composition about the complexity of time and space. Some of the imagery verges on the science-fictional (the second part’s titled “Hyperspace”), but it’s not necessarily sf itself. Similarly, “Jacob’s Ladder,” which concludes side one, is a seven-minute-plus song that describes the sun emerging from clouds, filled with nature imagery by way of mythic or fantastic language. Again, though, not explicitly fantasy.

Here and elsewhere Peart’s approaching things differently, getting at more realistic themes. So you can see sf imagery in “Entre Nous” (“We are planets to each other / Drifting in our orbits / To a brief eclipse”) and fantasy in “Different Strings” (“Who’s come to slay the dragon — / Come to watch him fall? / Making arrows out of pointed words / Giant killers at the call”), but Peart’s interests are elsewhere. He’s growing as a writer at the same time; I find his lyrics more sophisticated here, in language, image, and structure. But it’s incorrect to suggest that he ever fully abandoned sf.

Here and elsewhere Peart’s approaching things differently, getting at more realistic themes. So you can see sf imagery in “Entre Nous” (“We are planets to each other / Drifting in our orbits / To a brief eclipse”) and fantasy in “Different Strings” (“Who’s come to slay the dragon — / Come to watch him fall? / Making arrows out of pointed words / Giant killers at the call”), but Peart’s interests are elsewhere. He’s growing as a writer at the same time; I find his lyrics more sophisticated here, in language, image, and structure. But it’s incorrect to suggest that he ever fully abandoned sf.

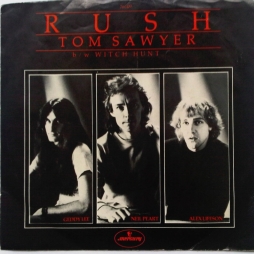

For example, the band’s next album, 1981’s Moving Pictures, featured a directly science-fictional song, “Red Barchetta.” Based on a 1973 short story by writer Richard Foster, the song describs a future in which a ‘motor law’ has outlawed many kinds of cars. The song’s young Nameless Protagonist (NP) has an uncle who keeps a car on a country farm, and most of the song describes NP’s Sunday drive and chase by massive futuristic vehicles. It’s a song about liberation through speed, about the power of journeying. (Similarly, the instrumental “YYZ” is named for the airport code of Toronto’s Pearson Airport — the title is, in fact, pronounced Canadian-style, ‘why-why-zed’ — and the music’s meant to evoke the sense of a journey, of travelling from place to place and spending time in a place between places.)

The album also features “Witch Hunt,” subtitled “Part III of Fear.” Future albums would count down, and then ahead, to fill out a series of songs about different aspects of fear. “Witch Hunt” is about the fear that drives the mob. It moves from horror-film imagery (“The night is black, / Without a moon. / The air is thick and still.”) to Peart’s by-now-longstanding theme of the horror of groupthink and ideological authority (“Silent and stern in the sweltering night, / The mob moves like demons possesed. / Quiet in conscience, calm in their right, / Confident their ways are best”). It’s not explicitly fantastic, but the suffocating sense of dread in the music and lyrics creates a sense of exceptional horror. It also points out, I think, Peart’s increasing power as a writer: here and elsewhere he convincingly evokes just the right emotional tone. Look at the recurring sibilance of the second quote; it’s a hissing, insinuating, threat.

The album also features “Witch Hunt,” subtitled “Part III of Fear.” Future albums would count down, and then ahead, to fill out a series of songs about different aspects of fear. “Witch Hunt” is about the fear that drives the mob. It moves from horror-film imagery (“The night is black, / Without a moon. / The air is thick and still.”) to Peart’s by-now-longstanding theme of the horror of groupthink and ideological authority (“Silent and stern in the sweltering night, / The mob moves like demons possesed. / Quiet in conscience, calm in their right, / Confident their ways are best”). It’s not explicitly fantastic, but the suffocating sense of dread in the music and lyrics creates a sense of exceptional horror. It also points out, I think, Peart’s increasing power as a writer: here and elsewhere he convincingly evokes just the right emotional tone. Look at the recurring sibilance of the second quote; it’s a hissing, insinuating, threat.

The longest song on the album is the eleven-minute “The Camera Eye,” an extensive evocation of the feel of two cities, New York and London. Peart’s said the title was a nod to John Dos Passos’ U.S.A. Trilogy, where the term’s used to introduce stream-of-consciousness passages. What I want to note here is that it seems to highlight another recurring image in Peart’s writing: the city. The elder race of “2112” had built a wondrous city of art, as had the followers of Apollo in “Hemispheres.” The city, for Peart, seems associated with complexity, with potential: “I feel the sense of possibilities, / I feel the wrench of hard realities. / The focus is sharp in the city.”

Moving Pictures was a huge commercial success, buoyed by two hit singles, “Tom Sawyer” and “Limelight.” Geddy Lee’s said that was the album on which the band felt they’d truly arrived as a group. Lee and guitarist Alex Lifeson were 27, Peart was 28.

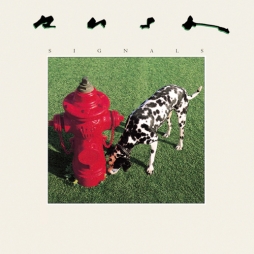

Signals, their next album, marked a tonal shift for the band, an increasing exploration of synthesizer sounds and studio effects. The resulting album felt colder, but, oddly, produced the band’s only highest-charting single in the US to date, “New World Man.”

Signals, their next album, marked a tonal shift for the band, an increasing exploration of synthesizer sounds and studio effects. The resulting album felt colder, but, oddly, produced the band’s only highest-charting single in the US to date, “New World Man.”

It kicked off with “Subdivisions,” a powerful song about the isolation of suburbia and the social hierarchies of the young. I’ve been avoiding posting links to YouTube videos because there don’t seem to be many officially-posted Rush songs, but I can’t resist posting this link to Jacob Moon’s acoustic take on “Subdivisions,” one of the best covers I’ve ever heard of any song. It demonstrates the strength of the band’s songwriting, and how for all their technical ability there’s a core of powerful emotion at the heart of all their work.

You can see Peart’s concern with dreams in “Subdivisions” — “Nowhere is the dreamer / Or the misfit so alone,” he writes, and “Some will sell their dreams for small desires / Or lose the race to rats / Get caught in ticking traps / And start to dream of somewhere / To relax their restless flight / Somewhere out of a memory / Of lighted streets on quiet nights…” This look ahead to a life that’s betrayed youthful promise recalls the old protagonist of “The Fountain of Lamneth” drinking away his later years; as we’ll see, the ‘restless flight’ also looks ahead to Clockwork Angels and another song about an older protagonist lost in memories of youth — this time lost in “Headlong Flight.”

“The Analog Kid” is yet another song about a youth eager to head out into the wide world: “A vague sensation quickens / In his young and restless heart / And a bright and nameless vision / Has him longing to depart” — to seek “Open sea and city lights / Busy streets and dizzy heights.” Sea, city, and mountain; three symbols of voyaging, all of which seem to keep turning up in Peart’s lyrics. But you can’t get away from everything. “Too many hands on my time,” thinks the Kid, or else the narrator. You can’t escape time.

“The Analog Kid” is yet another song about a youth eager to head out into the wide world: “A vague sensation quickens / In his young and restless heart / And a bright and nameless vision / Has him longing to depart” — to seek “Open sea and city lights / Busy streets and dizzy heights.” Sea, city, and mountain; three symbols of voyaging, all of which seem to keep turning up in Peart’s lyrics. But you can’t get away from everything. “Too many hands on my time,” thinks the Kid, or else the narrator. You can’t escape time.

“Chemistry” is another song about the difficulty of connecting with another individual — if Moving Pictures’ “Limelight” was an introvert’s lament, this song recalls the scientific approach of Permanent Waves’ “Entre Nous,” with chemical instead of astronomical imagery. “Digital Man” is a peculiar blend of paranoid pseudo-sf imagery — “He’s got a force field and a flexible plan / He’s got a date with fate in a black sedan” — and seems to demand to be taken as a contrast with “The Analog Kid.” Has the Kid grown up to a bleak digital future? If it weren’t for the fact that Signals came out in 1982, two years before Neuromancer, it’d be tempting to call the song cyberpunk.

“The Weapon” is the second part of “Fear,” about the way those in authority use fear to direct their people: “With an iron fist in a velvet glove / We are sheltered under the gun / In the glory game on the power train / Thy kingdom’s will be done.” Peart tells us here that “Even love must be limited by time,” again you see the theme of time becoming dominant in his writing. “New World Man” is another song about the conflict between romance and modern mechanisation, fitting in nicely with “The Analog Kid” and “The Digital Man.” “Losing It” is a meditation on the decay of an artist’s dream: “Some are born to move the world — / To live their fantasies / But most of us just dream about / The things we’d like to be.” Finally, “Countdown” depicts the launch of a space shuttle; as the countdown is time in its purest form, in the spacecraft science becomes myth: “This magic day when super-science / Mingles with the bright stuff of dreams.”

“The Weapon” is the second part of “Fear,” about the way those in authority use fear to direct their people: “With an iron fist in a velvet glove / We are sheltered under the gun / In the glory game on the power train / Thy kingdom’s will be done.” Peart tells us here that “Even love must be limited by time,” again you see the theme of time becoming dominant in his writing. “New World Man” is another song about the conflict between romance and modern mechanisation, fitting in nicely with “The Analog Kid” and “The Digital Man.” “Losing It” is a meditation on the decay of an artist’s dream: “Some are born to move the world — / To live their fantasies / But most of us just dream about / The things we’d like to be.” Finally, “Countdown” depicts the launch of a space shuttle; as the countdown is time in its purest form, in the spacecraft science becomes myth: “This magic day when super-science / Mingles with the bright stuff of dreams.”

So the whole album’s an interplay of Peart’s ongoing interests. Time and art. Travel and dreams. All these things explicated by means of science fictional imagery. Peart’s language has picked up an incredible allusuiveness, an ability to hint at multiple things at once; there’s a density to it.

Grace Under Pressure followed, another album built around heavy keyboards and studio technique, and another album filled with dystopic visions. The environmental destruction and nuclear paranoia of “Distant Early Warning” (the title a reference to the DEW line of radar stations in the Canadian Arctic that watched for Soviet bombers). The concentration camp described in “Red Sector A” — is it the past or future? The purely internal fear of “The Enemy Within,” Part I of the Fear Trilogy, which has counted down from fear of outsiders, to the way our fears are used against us by our leaders, to the instinctive fears and phobias we all have. “The Body Electric,” about a robot escaping from slavery, “A hundred years of routines,” only to break down and die, turning to an AI goddess in its last moments.

Grace Under Pressure followed, another album built around heavy keyboards and studio technique, and another album filled with dystopic visions. The environmental destruction and nuclear paranoia of “Distant Early Warning” (the title a reference to the DEW line of radar stations in the Canadian Arctic that watched for Soviet bombers). The concentration camp described in “Red Sector A” — is it the past or future? The purely internal fear of “The Enemy Within,” Part I of the Fear Trilogy, which has counted down from fear of outsiders, to the way our fears are used against us by our leaders, to the instinctive fears and phobias we all have. “The Body Electric,” about a robot escaping from slavery, “A hundred years of routines,” only to break down and die, turning to an AI goddess in its last moments.

Grace Under Pressure is a bleak album, appropriate for a record that comes from the date 1984. There’s no way out, no redeeming transcendental journey. The last song on the disc, “Between the Wheels,” is haunted by time: “To live between the wars / In our time — / Living in real time — / Holding the good time — / Holding on to yesterdays…” But the wheels of the title aren’t the wheels of an escaping Red Barchetta, nor are they the “wheels within wheels” described in Permanent Waves’ “Natural Science,” or at least not from the perspective we’re used to. Instead it’s a frightening empathy with the inescapable: “You know how that rabbit feels / Going under your speeding wheels / Bright images flashing by / Like windshields towards a fly / Frozen in the fatal climb — / But the wheels of time — / Just pass you by…” There’s something chilling about the precision of the rabbit going under the wheels, something brutal in the identification of the precise species of roadkill. (Although it has to be said the rabbit population would be restored in a future album, with a resonance precisely the opposite of the inescapability of this line.)

(And: You know how people find it an amusing piece of trivia that the first song MTV ever played was the Buggles’ “Video Killed The Radio Star,” and how it seemed to sum up the role of the new video network? The first video ever played by Muchmusic, Canada’s counterpart to MTV, was “The Enemy Within.” Make of that what you will.)

(And: You know how people find it an amusing piece of trivia that the first song MTV ever played was the Buggles’ “Video Killed The Radio Star,” and how it seemed to sum up the role of the new video network? The first video ever played by Muchmusic, Canada’s counterpart to MTV, was “The Enemy Within.” Make of that what you will.)

1985’s Power Windows continued the band’s synth-heavy 80s sound. As the title implies, it was concerned with power and the misapplication thereof. Peart’s interest in technology came out in “Manhattan Project,” about the development of the atomic bomb, but perhaps more fascinating was the album closer, “Mystic Rhythms.” Peart’s never shied away from expressing his basically secular worldview — Permanent Waves’ “Freewill” being perhaps his most direct statement — but here he considers “More things than are dreamed about / Unseen and unexplained / We suspend our disbelief / And we are entertained.” I think it’s fair to say that while Peart’s a rationalist, he’s fascinated by the point where the rational ends, where dreams take over. That’s what the hero of “The Fountain of Lamneth” finally finds; that’s what “Mystic Rhythms” seems to investigate.

It’s an investigation that perhaps continued in “Tai Shan,” a song from 1987’s Hold Your Fire album. The lyrics are a reflection by Peart on climbing Mount Tai, a sacred mountain in China. You can see more of Peart’s concerns in Hold Your Fire; the difficulty of communication between people (“Open Secrets”), the passage of time (“Time Stand Still,” “Turn the Page”), the importance of perseverence in chasing your artistic dreams (“The Mission”). It’s the apex of their 80s sound, with studio technique almost drowning out the guitars. I think it’s a hit-or-miss album; some of the songs are beautiful, some seem to drag. Much as Hemispheres marked the far end of one kind of sound for Rush, Hold Your Fire marked another outlier. After this album, they’d return to a more stripped-down guitar-oriented sound, starting on their next record.

It’s an investigation that perhaps continued in “Tai Shan,” a song from 1987’s Hold Your Fire album. The lyrics are a reflection by Peart on climbing Mount Tai, a sacred mountain in China. You can see more of Peart’s concerns in Hold Your Fire; the difficulty of communication between people (“Open Secrets”), the passage of time (“Time Stand Still,” “Turn the Page”), the importance of perseverence in chasing your artistic dreams (“The Mission”). It’s the apex of their 80s sound, with studio technique almost drowning out the guitars. I think it’s a hit-or-miss album; some of the songs are beautiful, some seem to drag. Much as Hemispheres marked the far end of one kind of sound for Rush, Hold Your Fire marked another outlier. After this album, they’d return to a more stripped-down guitar-oriented sound, starting on their next record.

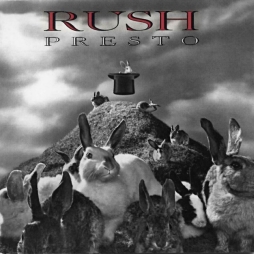

Presto came out in 1989, and while it’s not the most popular album among Rush fans, it’s not lacking for defenders (personally, I love it). It’s probably the most upbeat record the band had written in a long while. Instead of the distance between lovers, a song like “Chain Lightning” tells us that “Dreams are sometimes catching / Desire goes to my head / Love responds to your invitation / Love responds to imagination.” Later, “The Pass” is a strong anti-suicide note which reminds us that “All of us get lost in the darkness / Dreamers learn to steer by the stars / All of us do time in the gutter / Dreamers turn to look at the cars.” (It is a powerful thing to me to realise that I might never have had the chance the meet at least two people who’ve been very important to me in my life if not for this specific song.) Even the environmentalist “Red Tide” is ultimately an exhortation: “Now’s the time to make the time / While hope is still in sight / Let us not go gently / To the endless winter night.”

The title track is a heartfelt song with an astonishing lightness of touch. The magic it implies isn’t a Tolkienesque high wizardry; if anything, it’s a sense of enchantment, a knowledge of the wonder in everyday things: “I am made of the dust of the stars / And the oceans flow in my veins.” Literally it seems to be about a failed relationship, about a lack of magic; but then it’s also about illusion, memory, and dreams. Peart has mused before how often people are illusions to other people; here enchantment mixes with prestidigitation (the album cover shows a hovering top hat surrounded by confused rabbits, apparently unaware that they’ve magicaly transcended being crushed by relentless wheels). It’s a complex, engimatic song that I read differently every time I come to it.

The title track is a heartfelt song with an astonishing lightness of touch. The magic it implies isn’t a Tolkienesque high wizardry; if anything, it’s a sense of enchantment, a knowledge of the wonder in everyday things: “I am made of the dust of the stars / And the oceans flow in my veins.” Literally it seems to be about a failed relationship, about a lack of magic; but then it’s also about illusion, memory, and dreams. Peart has mused before how often people are illusions to other people; here enchantment mixes with prestidigitation (the album cover shows a hovering top hat surrounded by confused rabbits, apparently unaware that they’ve magicaly transcended being crushed by relentless wheels). It’s a complex, engimatic song that I read differently every time I come to it.

The next album, 1991’s Roll the Bones, was a step heavier than Presto. It was about chance, and taking chances, like the young folk of the opening song “Dreamlines,” who set off into the wide world to make their fortunes (as do so many young folk in Peart’s lyrics). The theme was another implicit statement of disbelief, as reflected in the lyrics of the title track: “Well, who would hold a price / On the heads of the innocent children / If there’s some immortal power / To control the dice?” Here, as so often before and since, Peart rejects an all-controlling God, and specifically rejects the idea that the injustice in the world is planned. When Peart writes here about “The Big Wheel,” he’s writing about the spinning wheel of fortune.

1993’s Counterparts was a heavier album again, raw and threatening. It introduced, or pointed up, another theme in Peart’s writing: the double. Apollo and Dionysus. New York to London (in “The Camera Eye”). The Analog Kid and the Digital Man. On this album, the doppelganger took many forms; it’s an album about confrontation with otherness. “Animate,” the first song, was a Jungian psychodrama, a man addressing his anima. “Between Sun and Moon” investigates “The gap between actor and act / The lens between wishes and fact.” “Alien Shore” depicts people divided by difference (of gender, of race) as swimmers in a vast sea struggling to the same unknown shore; and the sea again is an emblem for Peart, reaching back to the third section of “The Fountain of Lamneth,” to the opening lines of “Natural Science,” through the “High Water” of the last track of Hold Your Fire, and so on to here — the sea as a primordial, amniotic matrix out of which come our own origins.

1993’s Counterparts was a heavier album again, raw and threatening. It introduced, or pointed up, another theme in Peart’s writing: the double. Apollo and Dionysus. New York to London (in “The Camera Eye”). The Analog Kid and the Digital Man. On this album, the doppelganger took many forms; it’s an album about confrontation with otherness. “Animate,” the first song, was a Jungian psychodrama, a man addressing his anima. “Between Sun and Moon” investigates “The gap between actor and act / The lens between wishes and fact.” “Alien Shore” depicts people divided by difference (of gender, of race) as swimmers in a vast sea struggling to the same unknown shore; and the sea again is an emblem for Peart, reaching back to the third section of “The Fountain of Lamneth,” to the opening lines of “Natural Science,” through the “High Water” of the last track of Hold Your Fire, and so on to here — the sea as a primordial, amniotic matrix out of which come our own origins.

Test For Echo followed in 1996. As far as I can tell it’s not highly regarded by many fans, and Peart’s lyrics seem simpler than his usual work. You can still see his typical concerns in “Driven,” or a song like “Time and Motion” about the nature of connections between people. But in a way the most impressive aspect of Peart’s work on Test For Echo was his drumming. He’d begun working with a man named Freddie Gruber, a kind of drum guru. Gruber helped Peart to totally revise his entire drumming style; his whole physical approach to playing changed. For a man widely considered to be one of the best, even the best, in his field to so utterly rework his style strikes me as an incredible statement of artistic confidence, as well as a sign of someone who’s genuinely attempting to explore every facet of his art.

I haven’t spoken much, as I’ve gone over these albums, of the band’s personal lives. Generally speaking, the group’s work ethic kept them on the straight and narrow. They didn’t get caught up in drug addictions. They married fairly young. They concentrated on writing and playing music, and if they’d slowed down a bit through the 90s, that was unfortunate but understandable. But in 1997, tragedy struck.

I haven’t spoken much, as I’ve gone over these albums, of the band’s personal lives. Generally speaking, the group’s work ethic kept them on the straight and narrow. They didn’t get caught up in drug addictions. They married fairly young. They concentrated on writing and playing music, and if they’d slowed down a bit through the 90s, that was unfortunate but understandable. But in 1997, tragedy struck.

On August 10, 1997, Peart’s 19-year-old daughter was killed in a car accident. His wife, Jacqueline, died of cancer 10 months later; Peart’s convinced there’s a causal connection, that his wife effectively lost the desire to live after their daughter’s death. Peart took a long time to recover; much of his healing process is recounted in one of his books of memoirs, Ghost Rider. The act of travelling across the Americas by motorcycle helped him return to himself. He married his second wife in the year 2000; in 2001 he told Lee and Lifeson that he was ready to start work on a new Rush album.

The result, 2002’s Vapor Trails, is one of my personal favourites among their albums. There was something profoundly touching in reading the track listing, and coming across “Freeze (Part IV of Fear)” — it was as though the band was insisting on its own continuity across the half-dozen years of silence. Of course Peart’s lyrics had changed; they were edgier, more confrontational, filled with questions. Still, many were surprisingly optimistic: “One Little Victory,” “Ceiling Unlimited.” Musically, the album was heavier than the band had been in years, perhaps in their career; much criticism has in fact been directed at the album’s production, which tended to lose acoustic subtleties. There’ve been plans afoot for a while to remaster the album, but I have to say I think the thick, unyielding sound of the album fits its emotional terrain perfectly.

The result, 2002’s Vapor Trails, is one of my personal favourites among their albums. There was something profoundly touching in reading the track listing, and coming across “Freeze (Part IV of Fear)” — it was as though the band was insisting on its own continuity across the half-dozen years of silence. Of course Peart’s lyrics had changed; they were edgier, more confrontational, filled with questions. Still, many were surprisingly optimistic: “One Little Victory,” “Ceiling Unlimited.” Musically, the album was heavier than the band had been in years, perhaps in their career; much criticism has in fact been directed at the album’s production, which tended to lose acoustic subtleties. There’ve been plans afoot for a while to remaster the album, but I have to say I think the thick, unyielding sound of the album fits its emotional terrain perfectly.

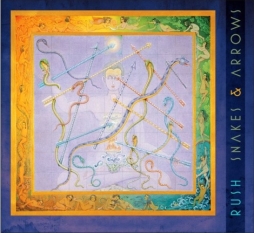

2004 saw the band produce an EP of cover songs, Feedback, and their next album, 2007’s Snakes and Arrows, seemed to be influenced by the songwriting values of their early influences. There was a directness in a lot of those songs, an open emotionalism. Lyrically, much of the album was concernced with religion: “When the Wind Blows” was a meditation on rising fanaticism “From the Middle East to the Middle West,” while “Faithless” insisted on the individual’s right to believe what they will.

As it happened, a couple of years later the band’s career got a boost from a relatively unexpected source. Canadian documentary filmmakers Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn, creators of the heavy metal documentaries Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal, along with the Iron Maiden concert film Flight 666, put together an excellent film about the band: Beyond the Lighted Stage. The documentary won the audience prize at the Tribeca Film Festival, and was nominated for a Grammy award. Something about the album seemed to strike a chord. Rush, never concerned with image or musical fashions, had never been critical darlings — but in the wake of the documentary, that began to change, at least a little. How many other bands had been around so long, and had put out so much music together? How many others had such a clear history of doing things their own way, and of following their own muses?

As it happened, a couple of years later the band’s career got a boost from a relatively unexpected source. Canadian documentary filmmakers Scot McFadyen and Sam Dunn, creators of the heavy metal documentaries Metal: A Headbanger’s Journey and Global Metal, along with the Iron Maiden concert film Flight 666, put together an excellent film about the band: Beyond the Lighted Stage. The documentary won the audience prize at the Tribeca Film Festival, and was nominated for a Grammy award. Something about the album seemed to strike a chord. Rush, never concerned with image or musical fashions, had never been critical darlings — but in the wake of the documentary, that began to change, at least a little. How many other bands had been around so long, and had put out so much music together? How many others had such a clear history of doing things their own way, and of following their own muses?

Perhaps none. Fans had always loved them — they’re third behind the Beatles and Rolling Stones for most consecutive gold or platinum albums — but at long last critics began evaluating the group seriously and honestly. Endurance, perhaps, had won out. And now, two years after the McFadyen/Dunn film, thirty-eight years after Neil Peart joined Rush, the band’s put out their first concept album. It’s a great work in itself; and, in many ways, it seems like a summation of lyrical themes Peart’s been fascinated with for years.

Wheels. Time. Dreams. Mountain, city, and sea. The distance between people. Magic and illusion. Journeys; ships and cars. False gods; machines and injustice. These are strong themes, strong images to work with. You can find others, in Peart’s writing, and specifically you can find things that seem to foreshadow Clockwork Angels. Cages, trains, diamonds, distant stars, angels. This album’s the product of a life and a career. It’s a complex story, that also hearkens back to perhaps Peart’s first truly ambitious lyrics. Next week, I’ll be looking at it in depth.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] because I had to have it that day. In reading what follows (the first of three posts, with part two here, and part three here), understand that I’m a fan, and that this has been my favourite rock group […]