Clockwork Angels I. Wonders in the World

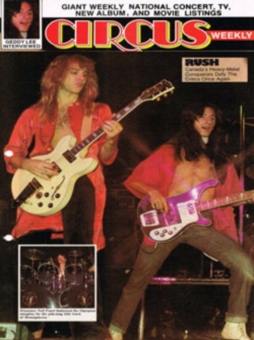

On June 12 the new album by veteran Canadian power-prog-rock trio Rush was released. I went out in pouring rain to buy a copy because I had to have it that day. In reading what follows (the first of three posts, with part two here, and part three here), understand that I’m a fan, and that this has been my favourite rock group for over two decades. But then there are few casual Rush fans: bassist and singer Geddy Lee’s said that he thinks of Rush as the biggest cult band in the world.

On June 12 the new album by veteran Canadian power-prog-rock trio Rush was released. I went out in pouring rain to buy a copy because I had to have it that day. In reading what follows (the first of three posts, with part two here, and part three here), understand that I’m a fan, and that this has been my favourite rock group for over two decades. But then there are few casual Rush fans: bassist and singer Geddy Lee’s said that he thinks of Rush as the biggest cult band in the world.

Clockwork Angels, the group’s 19th full-length studio release, is worth talking about here because it’s a picaresque steampunk concept album. It is, technically, the first concept album of the band’s career; they’ve written 20-minute songs before, and they’ve had albums that examined one theme through different angles (like Hold Your Fire, in which each song examined a different kind of emotion, or Roll the Bones, which looked at various aspects of chance), but never one that told a single story as they do here. Drummer and lyricist Neil Peart has spoken about how he wanted this album to represent his highest achievement as a writer and musician; he set himself a considerable challenge, and I think pulled it off. The record eschews narration and plot-oriented lyrics, instead including brief sections of narrative prose in the album booklet while the songs present emotional high points and sometimes move the plot forward. It’s oddly like listening to the songs from a musical, with an accompanying plot synopsis. A full treatment of the story will be coming in September, with the publication of a novelisation of the album by Kevin J. Anderson.

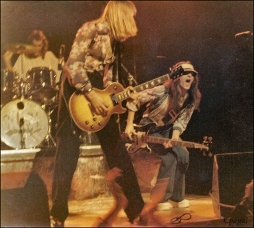

Musically, the album’s astonishing. Peart, Lee, and guitarist Alex Lifeson are widely acknowledged to be among the best in their field technically. That’s strongly in evidence here. Lee’s playing in particular is astonishing, unpredictable and intricate, but all three band members seem to push themselves as writers and musicians. Like much of their work, it’s heavy, guitar-oriented rock, but with a distinct feel that comes from the sophistication of the musicianship. It’s classic Rush, of a piece with their last two albums, 2002’s Vapor Trails and 2007’s oddly meditative Snakes and Arrows, but with a songwriting sensibility that seems to recall 2004’s Feedback. Feedback was an EP of covers of songs that had influenced the band early in their career, old-time classic rock by bands like Blue Cheer and The Who; to an extent, I think that directness and accessibility can be heard not only on Snakes and Arrows but on Clockwork Angels. At the same time, the new album’s something of a return to experiments with longer forms — two songs are more than seven minutes long, and one’s 6:51. It may be their most effective fusion of prog sophistication and rock concision.

Musically, the album’s astonishing. Peart, Lee, and guitarist Alex Lifeson are widely acknowledged to be among the best in their field technically. That’s strongly in evidence here. Lee’s playing in particular is astonishing, unpredictable and intricate, but all three band members seem to push themselves as writers and musicians. Like much of their work, it’s heavy, guitar-oriented rock, but with a distinct feel that comes from the sophistication of the musicianship. It’s classic Rush, of a piece with their last two albums, 2002’s Vapor Trails and 2007’s oddly meditative Snakes and Arrows, but with a songwriting sensibility that seems to recall 2004’s Feedback. Feedback was an EP of covers of songs that had influenced the band early in their career, old-time classic rock by bands like Blue Cheer and The Who; to an extent, I think that directness and accessibility can be heard not only on Snakes and Arrows but on Clockwork Angels. At the same time, the new album’s something of a return to experiments with longer forms — two songs are more than seven minutes long, and one’s 6:51. It may be their most effective fusion of prog sophistication and rock concision.

But with all this said, I found myself involved with the story of the album, the lyrical themes Peart plays with, and the way those themes have recurred in his work, just as the fantastic has always played a strong part in his writing. So to speak meaningfully about this album I need to write about the band’s history with sf and fantasy. And that in turn means looking back across the band’s career.

I should note that in what follows, I’m interested mainly in lyrics. And Peart’s lyrics, somewhat like the band in general, seem to be a love-them-or-hate-them affair. I think they’re great. Others don’t, and I can’t honestly say why; I can’t find any critical descriptions of the lyrics that I can really engage with. Most seem to use general labels like “preachy” or “pretentious,” and all you can really say to labels without reasoning or examples is: I disagree.

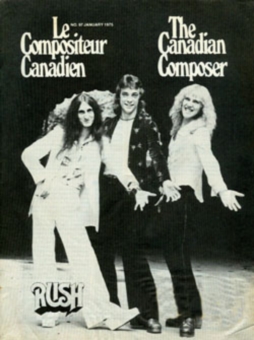

So let’s begin with Peart. He took up the drums at 13, played in various bands through his teen years, and at 18 moved from Port Dalhousie, Ontario (now Saint Catherines), to London, England, to try to make a living as a professional musician. After a year and a half, frustrated, he returned to Canada to take a job with his father selling farm machinery. Then, as it happened, he auditioned for a local band with an album under their belt that was looking for a drummer.

So let’s begin with Peart. He took up the drums at 13, played in various bands through his teen years, and at 18 moved from Port Dalhousie, Ontario (now Saint Catherines), to London, England, to try to make a living as a professional musician. After a year and a half, frustrated, he returned to Canada to take a job with his father selling farm machinery. Then, as it happened, he auditioned for a local band with an album under their belt that was looking for a drummer.

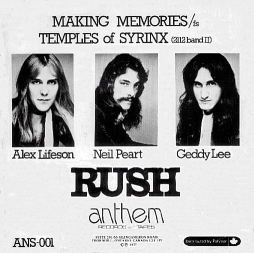

Rush was in a difficult position. Like Peart, Lee and Lifeson were young men from hardworking middle-class families, with no post-secondary education. High school friends, both children of immigrants, they’d formed their band with a third friend, John Rutsey, on drums. They’d released a single, and a loud Zeppelinesque self-titled album which had been played heavily by a radio station in Cleveland. There was some buzz behind the group, but Rutsey was diabetic, and his health was an issue, hindering plans to put together a long tour. Lee and Lifeson had to ask him to leave the band, and to look for another drummer. They found Peart. And in Peart, they also found a budding lyricist.

Rutsey’d originally been tapped to write lyrics for the first album, but couldn’t come up with anything that satisfied him. Lee ultimately wrote some words at the last minute, but didn’t want to continue writing. He and Lifeson soon realised that Peart was a reader, and asked him to contribute lyrics for the next album. Peart agreed. His first song became the title track: “Fly by Night.”

Rutsey’d originally been tapped to write lyrics for the first album, but couldn’t come up with anything that satisfied him. Lee ultimately wrote some words at the last minute, but didn’t want to continue writing. He and Lifeson soon realised that Peart was a reader, and asked him to contribute lyrics for the next album. Peart agreed. His first song became the title track: “Fly by Night.”

Peart was 21 when he joined Rush, 22 when Fly By Night was recorded over three days in February of 1975; a year older than Lee and Lifeson but still, as writers go, incredibly young. It’s unsurprising that he wore his influences on his sleeve. The quiet Tolkien-inspired “Rivendell” was one example. “Anthem” was another, a song inspired by Ayn Rand’s Objectivist philosophy. Rand’s generally scoffed at by professional philosophers, and I can’t say I care much for her prose writing style. But I’ve noticed that her philosophy, with its libertarian focus on the importance of the individual, seems to resonate with the young; she’s a phase a number of people go through. Peart was one of them.

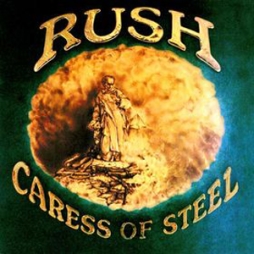

Also of note on that album was “By-Tor and the Snow Dog.” Lyrically it’s fairly simple, a brief description of a fight between a mystic hound and a demonic prince, but there’s something captivating in its unabashed use of fantasy imagery that’s perhaps less psychedelic than it is mythic. More importantly, at over eight minutes in length, divided into numbered movements, it showed the band trying out more elaborate structures than the typical three-to-five-minute rock song. Later that year, their next album, Caress of Steel, would go much further.

Also of note on that album was “By-Tor and the Snow Dog.” Lyrically it’s fairly simple, a brief description of a fight between a mystic hound and a demonic prince, but there’s something captivating in its unabashed use of fantasy imagery that’s perhaps less psychedelic than it is mythic. More importantly, at over eight minutes in length, divided into numbered movements, it showed the band trying out more elaborate structures than the typical three-to-five-minute rock song. Later that year, their next album, Caress of Steel, would go much further.

Caress opened with three fairly direct hard-rock songs, including the excellent “Bastille Day,” then followed with the twelve-minute-long “The Necromancer,” which continued By-Tor’s story with the villain inexplicably switched to hero. It’s a three-part fantasy story, in which three travellers, “Men of Willowdale” (Willowdale being the Toronto suburb where Lee and Lifeson grew up), are captured by the evil wizard of the title. The wizard’s about to lock them away in his dungeon when By-Tor arrives on the scene and kills the wizard, whose spirit departs for other worlds. It’s fun, and inventive musically, but although it works as a story it’s lyrically slight. Peart would try to fuse deeper themes with narrative in the album’s next, and last, song.

The whole second side of the album was taken up by the 20-minute suite “The Fountain of Lamneth.” Like Clockwork Angels, it’s a picaresque story about a young man seeking his fortune and a meaning for his life. It’s ambitious, but I don’t think it fully realised those ambitions; Peart wasn’t the writer he’d later become, and his technical ability with words and poetic devices wasn’t fully developed. His images don’t have the multiplicity of meaning and resonance that he’d later cultivate. Occasionally he falls into cliché. Still, the song was his most extensive lyrical statement up to that point. And as I think it seems to bear on the new album, I want to look at it in a bit of depth.

The whole second side of the album was taken up by the 20-minute suite “The Fountain of Lamneth.” Like Clockwork Angels, it’s a picaresque story about a young man seeking his fortune and a meaning for his life. It’s ambitious, but I don’t think it fully realised those ambitions; Peart wasn’t the writer he’d later become, and his technical ability with words and poetic devices wasn’t fully developed. His images don’t have the multiplicity of meaning and resonance that he’d later cultivate. Occasionally he falls into cliché. Still, the song was his most extensive lyrical statement up to that point. And as I think it seems to bear on the new album, I want to look at it in a bit of depth.

Firstly, it’s worth pointing out that here, as in later extended songs, Peart doesn’t give his protagonist a name. Let’s just call him, all of them, ‘NP’; the nameless protagonist signifying his creator. I think it’s inaccurate to say that these heroes are all the same, but there is a unity to them. Different possible incarnations of the same person, let’s say; the same person driven by different dreams.

Part I of “The Fountain of Lamneth” is “In the Valley,” beginning with NP’s birth and early childhood. “Just one blur I recognize / The one that soothes and feeds / My way of life is easy / And as simple are my needs,” he says, but he’s troubled by a nearby mountain, that hides the morning sun: “Yet my eyes are drawn toward / The mountain in the east / Fascinates and captivates / Gives my heart no peace.” So early on the song sets up an implicit conflict between the easy life of material things, and the intimation of something else, something harder to define. The mountain becomes a symbol of the desire that drives him: “I live to climb that mountain to / The Fountain of Lamneth.”

The rest of the song follows the winding road NP takes, through a long life, before he finally reaches the summit. Part II, “Didacts and Narpets,” sees him caught in a shouted dialogue with his professors (didacts) and parents (narpets, an early example of Peart’s fascination with anagrams): “Learn! Live! / Earn! Give!” Then the song skips forward some years, to Part III, “No One At The Bridge.” It seems that the struggle with authority figures has resulted in NP turning away from his dream of the mountain. Now he’s the captain of a wrecked sailing ship, all alone, lashed to the mast and with a maelstrom near, remembering when he first went to sea; the thrill of journeying to new lands. If his situation sounds vaguely like the Odyssey, then it’s perhaps not surprising that Part IV, “Panacea,” sees him wash ashore in the realm of a woman — the Panacea of the title — who becomes his lover. But, in the grand tradition of rock songs about wandering men, something pulls him onward; he leaves her.

The rest of the song follows the winding road NP takes, through a long life, before he finally reaches the summit. Part II, “Didacts and Narpets,” sees him caught in a shouted dialogue with his professors (didacts) and parents (narpets, an early example of Peart’s fascination with anagrams): “Learn! Live! / Earn! Give!” Then the song skips forward some years, to Part III, “No One At The Bridge.” It seems that the struggle with authority figures has resulted in NP turning away from his dream of the mountain. Now he’s the captain of a wrecked sailing ship, all alone, lashed to the mast and with a maelstrom near, remembering when he first went to sea; the thrill of journeying to new lands. If his situation sounds vaguely like the Odyssey, then it’s perhaps not surprising that Part IV, “Panacea,” sees him wash ashore in the realm of a woman — the Panacea of the title — who becomes his lover. But, in the grand tradition of rock songs about wandering men, something pulls him onward; he leaves her.

He doesn’t seem to get very far. Part V, “Bacchus Plateau,” finds NP living through “Another endless day,” and drinking away his nights. “Another foggy dawn / The mountain almost gone / Another doubtful fear / The road is not so clear / My soul grows ever weary / And the end is ever near.” He’s gotten old, and lost his youthful vision. But the conclusion of the song, “The Fountain,” sees him pull things together. “Look… the mist is rising / And the sun is peeking through.” What does he find, when he reaches the top of the mountain? “Life is just a candle / And a dream must give it flame.” The sun appears again, and NP has a moment of identification with it: “Like Old Sol behind the mountain / I’ll be coming up again…” and just as the song began with simple, infantile self-assertion (“I am born / I am me / I am new / I am free”) it ends with equally simple but more ambiguous statements of identity (“I’m together / I’m apart / I’m forever / At the start / Still… I am”).

It’s clever, but it doesn’t always hold together. It’s not clear how or why NP turns away from the mountain, or why he leaves Panacea only to be lost in memory and drink. And while the lyrical ideas make sense thematically, they’re often more impressive conceptually than as words with power in and of themselves. The music’s varied, perhaps too much so; it seems sometimes passionless, and uncharacteristically tentative. It’s a laudable attempt to integrate new structures and approaches into the band’s vocabulary, but I’m not sure it always works.

The album didn’t do very well commercially. That’s not entirely surprising; an audience primed to expect Zeppelin-like hard rock was always going to be wrong-footed by an album that switched tones a third of the way through to Genesis-like prog. Still, it was a disappointment, both to the band and the record label. The label in fact began to push the band to abandon their attempts at complexity, and go back to “Led Zeppelin, Junior” mode. The name of Bad Company was given them as a model.

The album didn’t do very well commercially. That’s not entirely surprising; an audience primed to expect Zeppelin-like hard rock was always going to be wrong-footed by an album that switched tones a third of the way through to Genesis-like prog. Still, it was a disappointment, both to the band and the record label. The label in fact began to push the band to abandon their attempts at complexity, and go back to “Led Zeppelin, Junior” mode. The name of Bad Company was given them as a model.

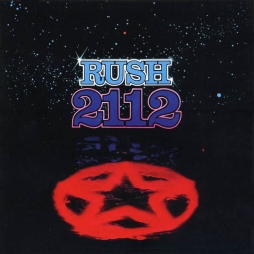

The band’s response was to come back the next year with an album that led off with a side-long track. A minute longer than “The Fountain of Lamneth,” this song was no mere bildungsroman; it was a full-on science fiction epic. It was the title track for the album, and since it was named for the year in which it was set, that meant the record that’d determine the band’s future one way or the other would be known only by a four-digit number. It was a breathtakingly defiant act of imaginative assertion. It wasn’t just that the band was writing science fiction. It was that they were writing it because that was who they were, who they had to be. They fought for their right not to be a party band.

It paid off: 2112 brought them into the Top 100 for the first time in their career. It was fast, aggressive, furious; maybe faster and more aggressive than any other band up to that point. In retrospect, the album marks a clear step forward in the evolution of what was then only beginning to be known as heavy metal (compare, if you like, 2112 with Judas Priest’s Sad Wings of Destiny, released the same year and also built around a side-long composition; I’d argue 2112 is the more aggressive album by far). It was, especially on that first side, passionate and precise, with long, driving instrumental breaks that somehow seemed to tell the story of the song almost as much as the lyrics did.

It paid off: 2112 brought them into the Top 100 for the first time in their career. It was fast, aggressive, furious; maybe faster and more aggressive than any other band up to that point. In retrospect, the album marks a clear step forward in the evolution of what was then only beginning to be known as heavy metal (compare, if you like, 2112 with Judas Priest’s Sad Wings of Destiny, released the same year and also built around a side-long composition; I’d argue 2112 is the more aggressive album by far). It was, especially on that first side, passionate and precise, with long, driving instrumental breaks that somehow seemed to tell the story of the song almost as much as the lyrics did.

That tale was also filled in by the liner notes, which — something like Clockwork Angels — contined passages of narrative prose adding to the tale. After an instrumental overture, we’re told about the setting from the perspective of the rulers of this dystopian future: the Priests of Syrinx, who regulate all things with their “great computers,” ensuring a Brave New World-like society of relentless mediocrity: “Look around this world we made / Equality our stock in trade / Come and join the Brotherhood of Man / Oh what a nice contented world / Let the banners be unfurled / Hold the Red Star proudly high in hand.”

But then the song’s NP finds a hidden cave behind a waterfall, and in that cave is an ancient musical instrument: an acoustic guitar, which he learns to play, creating a music more powerful than what the priests produce in the temples. He brings it to them, eager to demonstrate his new art, but the priests aren’t receptive. They destroy the guitar. NP returns to his home, where he has a strange dream, in which an Oracle shows him how things used to be, in an era before the Priests took power, when an “elder race” created powerful, individualistic art. This is in fact how things still are, somewhere in the universe, where “The elder race still learn and grow.” He dreams that they’ll return to throw down the temple — but when he awakes, nothing’s changed.

But then the song’s NP finds a hidden cave behind a waterfall, and in that cave is an ancient musical instrument: an acoustic guitar, which he learns to play, creating a music more powerful than what the priests produce in the temples. He brings it to them, eager to demonstrate his new art, but the priests aren’t receptive. They destroy the guitar. NP returns to his home, where he has a strange dream, in which an Oracle shows him how things used to be, in an era before the Priests took power, when an “elder race” created powerful, individualistic art. This is in fact how things still are, somewhere in the universe, where “The elder race still learn and grow.” He dreams that they’ll return to throw down the temple — but when he awakes, nothing’s changed.

The NP retreats to the cave where he found the guitar, the noise of the waterfall his last comfort. It’s not enough; he commits suicide. Then, after he dies, something happens, a battle depicted in an instrumental Grand Finale to match the overture; the song ends with a voice declaring “We have assumed control.”

It’s all surprisingly effective. Dramatically, it looks like it shouldn’t work. The different sections don’t seem to be linked by cause and effect. The finding of the guitar and the return of the elder race look like they ought to be somehow linked, but there’s no explicit connection. The lyrics are direct, but still sometimes fall into cliché: “Dream can’t you show me the light?” An uncharitable reading would say it’s kitsch about fighting tyranny with The Power Of Rock.

It’s all surprisingly effective. Dramatically, it looks like it shouldn’t work. The different sections don’t seem to be linked by cause and effect. The finding of the guitar and the return of the elder race look like they ought to be somehow linked, but there’s no explicit connection. The lyrics are direct, but still sometimes fall into cliché: “Dream can’t you show me the light?” An uncharitable reading would say it’s kitsch about fighting tyranny with The Power Of Rock.

But it isn’t, really. To start with, on a literal level, rock relies on the electric guitar, and NP finds an acoustic instrument. In fact, the louder rock or proto-metal sections are associated with the Priests (who, inverting tradional Christian musicology, get all the best tunes) and, to a lesser extent, the concluding battle with the elder race. Mainly, though, there isn’t a real sense of triumph. The man who finds the guitar dies on his own in the wild, again recalling Brave New World. The dream of art can’t survive the destruction of the instrument. That pathos, highly wrought as it may be, helps complicate the song enough for it to work.

There’s also a certain ambiguity of symbol that helps make the lyrics work as something like a parable. A syrinx is a kind of Pan pipe, a musical instrument of its own — but one with dark connotations, going back to the original story of the nymph Syrinx. The red star evokes both the traditional colour of communism and the geometrical symbol of the stars-and-stripes. And there’s something intriguing about the way that the song’s a part of itself; the way NP’s first plucking at the guitar is actually in the song, so we can hear a kind of aural montage of his development as a musician, learning more complex forms.

There’s also a certain ambiguity of symbol that helps make the lyrics work as something like a parable. A syrinx is a kind of Pan pipe, a musical instrument of its own — but one with dark connotations, going back to the original story of the nymph Syrinx. The red star evokes both the traditional colour of communism and the geometrical symbol of the stars-and-stripes. And there’s something intriguing about the way that the song’s a part of itself; the way NP’s first plucking at the guitar is actually in the song, so we can hear a kind of aural montage of his development as a musician, learning more complex forms.

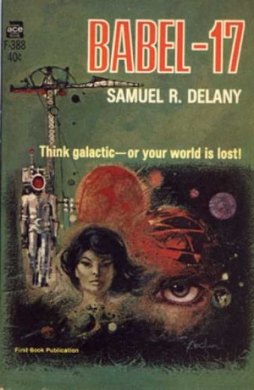

There’s no getting around the fact that the song works for many people because it has a simple and direct message. And it was a message that came with a share of controversy. While working on the song, Peart realised it was similar in many ways to a book he’d greatly enjoyed, Ayn Rand’s Anthem. He decided to acknowledge this with a refence in the liner notes to “the genius of Ayn Rand.” That got the band falsely branded as disciples of Rand’s Obectivism; they’ve since moved away from that statement, especially Peart, who seems temperamentally unsuited to be anybody’s disciple. He’s stated, for example, that “2112” owes quite a lot to another book he greatly enjoyed, Samuel Delaney’s Babel-17. Delaney and Rand are an odd mix, but perhaps those dissonant influences help explain the lasting fascination of the song.

It’s worth mentioning that the second half of the album isn’t bad at all, in particular a song Peart wrote to celebrate one of his favourite TV shows, “The Twilight Zone.” But I think it’s the album closer, the scorching “Something For Nothing,” that stands as an interesting counterpart to “2112” and especially to the suicide of the hero. It’s a song emphasising the importance of work, of applying oneself to one’s passion: “You don’t get something for nothing / You can’t have freedom for free / You won’t get wise / With the sleep still in your eyes / No matter what your dreams might be.” The work is useless without the inspiration of the dream, but the dream can’t be realised unless you work for it. Listen to the band members in an interview these days reflecting on why they’re still together, why they’re making music after almost four decades as a unit, and they’ll sooner or later talk about the importance of working hard at what they do.

What I want to get at here is this: at the age of 24, Peart as a writer had found themes and structures that had significance to him, and which continue to echo through his writing to the present day. The dream in conflict with the easy life. The artist in conflict with society. The use of multiple songs, or multiple structures within a song, to tell a story. And the use of science fictional imagery to suggest something mythic.

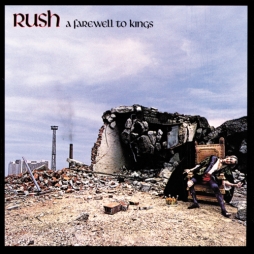

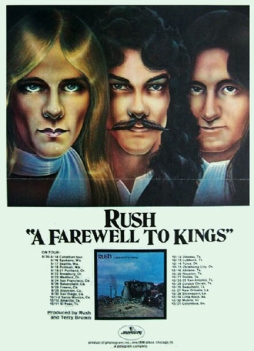

After putting out a live album later in 1976, Rush followed 2112 the next year with A Farewell to Kings. It broke new ground for the band, as Geddy Lee added keyboards to his already-busy bass playing. There were no side-long tracks, but two songs topped ten minutes. The title piece was puzzling, seemingly a conservative-sounding lament for a vanished age of integrity. You could perhaps read it as a contrast with “Bastille Day” from Caress of Steel, but I think what it does is establish the idea of a corrupt society which the other songs on the album react to in one way or another — either depicting attempts at reforming it (“Closer to the Heart,” “Cinderella Man”), escaping it (“Xanadu,” “Cygnus X-1”), or simply trying to struggle on through (“Madrigal”).

After putting out a live album later in 1976, Rush followed 2112 the next year with A Farewell to Kings. It broke new ground for the band, as Geddy Lee added keyboards to his already-busy bass playing. There were no side-long tracks, but two songs topped ten minutes. The title piece was puzzling, seemingly a conservative-sounding lament for a vanished age of integrity. You could perhaps read it as a contrast with “Bastille Day” from Caress of Steel, but I think what it does is establish the idea of a corrupt society which the other songs on the album react to in one way or another — either depicting attempts at reforming it (“Closer to the Heart,” “Cinderella Man”), escaping it (“Xanadu,” “Cygnus X-1”), or simply trying to struggle on through (“Madrigal”).

“Xanadu” seems to repudiate the title track’s search for nobility in the past, as the song’s NP, seeking immortality, is guided by “an ancient book” to “frozen mountain tops / Of eastern lands unknown” where he finds the lost realm of Xanadu. Taking liberal inspiration from Coleridge’s poem, NP here comes to a bad end: “A thousand years / have come and gone / But time has passed me by … Held within The Pleasure Dome / Decreed by Kubla Khan / To taste my bitter triumph / As a mad immortal man / Nevermore shall I return / Escape these caves of ice / For I have dined on honey dew / And drunk the milk of Paradise.”

It’s a favorite song among many Rush fans; complex and atmospheric, it’s also richly suggestive. I find that the more I listen to it the more evocative it becomes. It’s program music, with an appropriately Romantic theme; the lyrics don’t start until about five minutes into the song. It’s an example of the distinction between Rush and many other rog-rock bands: nothing feels wasteful. The instrumental breaks have a structure and develop emotional ideas with an unusual discipline. If you’re at all susceptible to the appeal of Rush’s music, “Xanadu” succeeds in creating a sense of awe.

It’s a favorite song among many Rush fans; complex and atmospheric, it’s also richly suggestive. I find that the more I listen to it the more evocative it becomes. It’s program music, with an appropriately Romantic theme; the lyrics don’t start until about five minutes into the song. It’s an example of the distinction between Rush and many other rog-rock bands: nothing feels wasteful. The instrumental breaks have a structure and develop emotional ideas with an unusual discipline. If you’re at all susceptible to the appeal of Rush’s music, “Xanadu” succeeds in creating a sense of awe.

Once again, it’s about a dreamer, a driven man — and I’d note that like “The Fountain of Lamneth” it’s about a man driven to the top of a mountain. But this time the dream’s a trap. Seeking escape isn’t enough. NP’s quest here is ultimately unnatural and even solipsistic: immortality for him alone, the hope of being “the last immortal man.” Of course his immortality is a trap; of course he goes mad. “Time and Man alone / Searching for the lost — Xanadu.” You can’t escape the passage of time. Or, more precisely, you can, but that’s worse than being caught up in it.

“Closer to the Heart” is next, a short, anthemic, and surprisingly idealistic piece, an almost innocent picture of a society standing in sharp contrast to the corruption envisioned in “A Farewell to Kings.” “Cinderella Man” follows, a fable with lyrics by Lee based on Frank Capra’s movie Mr. Deeds Goes to Town. Then “Madrigal,” on the one hand a soft love song and on the other a song about continuing to push onward against an unyielding world, using fantastic, chivalric, imagery to make the point: “When the dragons grow too mighty / To slay with pen or sword / I grow weary of the battle / And the storm I walk toward.”

The album concludes with “Cygnus X-1,” subtitled “Book 1 — The Voyage.” Mixing space rock and aggressive jazz rhythms, it’s a peculiar song about an NP in a spaceship named for Don Quixote’s horse, Rocinante, who travels into the heart of a black hole. If the rest of the album had an archaic note running through most of the songs — castles in the distance, ancient books, blacksmiths and plowmen, Cinderella, mighty dragons — “Cygnus X-1” seemed purely science-fictional, but for the name of the spaceship and the mythic name of the black hole itself. It also seemed to present a successful escape or transcendence, a contrast to “Xanadu.” The song begins by asking if there’s something other than death, or beyond death, through the black hole; it ends with the journey across the event horizon, and the implication of life going on. It’s a cliffhanger, to be continued on the next record.

The album concludes with “Cygnus X-1,” subtitled “Book 1 — The Voyage.” Mixing space rock and aggressive jazz rhythms, it’s a peculiar song about an NP in a spaceship named for Don Quixote’s horse, Rocinante, who travels into the heart of a black hole. If the rest of the album had an archaic note running through most of the songs — castles in the distance, ancient books, blacksmiths and plowmen, Cinderella, mighty dragons — “Cygnus X-1” seemed purely science-fictional, but for the name of the spaceship and the mythic name of the black hole itself. It also seemed to present a successful escape or transcendence, a contrast to “Xanadu.” The song begins by asking if there’s something other than death, or beyond death, through the black hole; it ends with the journey across the event horizon, and the implication of life going on. It’s a cliffhanger, to be continued on the next record.

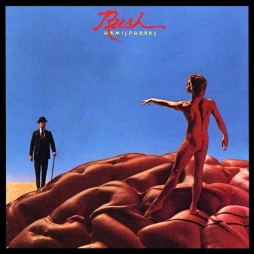

Which it was, with some difficulty. 1978’s Hemispheres album was the most technically demanding album Rush had yet created, filled with extensive compositions of incredibly complex music. Recording the album was apparently quite stressful. In the band’s history it represents the high-water mark for a certain approach both musically and lyrically; after this, the songs would be tighter, more focussed. Hemispheres represented the culmination of the band’s experimentation with musical epic.

It began with the third side-long track of the band’s career. “Cygnus X-1: Book 2 — Hemispheres” started off with an instrumental overture, then a narrative prologue establishing a world divided between “gods of love and reason.” The subsequent parts of the song each had a mythic name, vaguely recalling the movements of Holst’s The Planets. “Apollo: Bringer of Wisdom” has the god promise his followers “a world of wonder,” a world over which they would have control: “Through the endless winter storm / You can live in grace and comfort / In the world that you transform.” But those who followed him found the drive for accomplishment fading: “the urge to build these fine things / Seemed not to be so strong.” They crossed “the bridge of death” to Apollo’s rival, Dionysus.

It began with the third side-long track of the band’s career. “Cygnus X-1: Book 2 — Hemispheres” started off with an instrumental overture, then a narrative prologue establishing a world divided between “gods of love and reason.” The subsequent parts of the song each had a mythic name, vaguely recalling the movements of Holst’s The Planets. “Apollo: Bringer of Wisdom” has the god promise his followers “a world of wonder,” a world over which they would have control: “Through the endless winter storm / You can live in grace and comfort / In the world that you transform.” But those who followed him found the drive for accomplishment fading: “the urge to build these fine things / Seemed not to be so strong.” They crossed “the bridge of death” to Apollo’s rival, Dionysus.

“Dionysus: Bringer of Love” gives his new followers a hedonistic life based on love; for a while. “But the winter fell upon them / And it caught them unprepared / Bringing wolves and cold starvation / And the hearts of men despaired.” So war breaks out between the gods — “Armageddon: the Battle of Heart and Mind.” The heart and the mind go to war, a conflict of hemispheres; specifically, the left and right hemispheres of the brain (the “bridge of death” symbolised the corpus callosum, which connects the hemispheres). But in the middle of the war, a Nameless Protagonist builds a rocketship, Rocinante, and flies into the mystery at the heart of the black hole; this is Book 1, right in the middle of Book 2. As it turns out, what lies at the heart of the black hole is Olympus. NP is apotheosised as a new god — “Cygnus: Bringer of Balance.” The balance brings peace, and so the war ends.

Peart’s trying something interesting here, trying to create a new myth. Personally, I find the allegory’s a bit too direct, and the symbolism of Apollo and Dionysus, while not something you expect to find in a rock song, is obvious; and at this point Peart’s rhymes are still simple, if adequate. It’s interesting, but not always moving. The integration of “Cygnus X-1: Book 1” is structurally effective, though, and certainly musically the song’s impeccable.

Peart’s trying something interesting here, trying to create a new myth. Personally, I find the allegory’s a bit too direct, and the symbolism of Apollo and Dionysus, while not something you expect to find in a rock song, is obvious; and at this point Peart’s rhymes are still simple, if adequate. It’s interesting, but not always moving. The integration of “Cygnus X-1: Book 1” is structurally effective, though, and certainly musically the song’s impeccable.

(As a contrast, I think “The Trees,” on the second side of the album, is an example of a parable that works. It works not because it has a single obvious application, but because, like most effective fables, it can be applied in a number of ways.)

“Cygnus X-1” turns out to be a paean to balance, to equilibrium. It seems like a contrast to the enforced mediocrity of “2112,” but it’s also an implicit counterpoint to couple other recurring themes for Peart turn up in “Hemispheres.” A couple other themes turn up in the song which would become significant for Peart later. The gods, it seems, are fallible; Apollo and Dionysus are incomplete, just as the priests of Syrinx are not to be trusted. Authority is suspect. And: here as elsewhere, a voyage is critical. Peart’s an avid cyclist and motorcyclist, who’s written books about his travels around the world; it’s hard not to see his emphasis on the transformative power of the journey as touching something deep in his psyche.

Above all, though, what leaps out from “Hemispheres” and from these early Rush albums as a whole is the use of fantasy and science fiction. It’s difficult to imagine now, but at the time these things weren’t usual for mainstream entertainment, and I suspect that might have helped fuel early negative reactions to the band. There was some fantasy in rock music, of course, going back at least to the psychedelic rock of the mid-60s. I think you could argue that Rush, who isn’t psychedelic in any meaningful way, did something different with the fantastic, something less whimsical and more consciously mythic. It was clearer and more directly narrative than what you’d find in Pink Floyd or Hawkwind, less coyly whimsical than early Genesis and Bowie (I say this neither to criticise nor praise, but simply to try to evaluate). I suspect it’s had a direct influence on later heavy metal, which of all rock genres may make the most extensive use of fantasy subjects.

Above all, though, what leaps out from “Hemispheres” and from these early Rush albums as a whole is the use of fantasy and science fiction. It’s difficult to imagine now, but at the time these things weren’t usual for mainstream entertainment, and I suspect that might have helped fuel early negative reactions to the band. There was some fantasy in rock music, of course, going back at least to the psychedelic rock of the mid-60s. I think you could argue that Rush, who isn’t psychedelic in any meaningful way, did something different with the fantastic, something less whimsical and more consciously mythic. It was clearer and more directly narrative than what you’d find in Pink Floyd or Hawkwind, less coyly whimsical than early Genesis and Bowie (I say this neither to criticise nor praise, but simply to try to evaluate). I suspect it’s had a direct influence on later heavy metal, which of all rock genres may make the most extensive use of fantasy subjects.

The Hemispheres album closed with the extensive instrumental “La Villa Strangiato,” a piece of mind-boggling complexity. In the long run, though, perhaps the most significant song for the band was the briefest: “Circumstances,” with autobiographical lyrics about Peart’s experiences as a young man in London. Peart would grow more involved with the contemporary world in his lyrics, more grounded in concrete details. But his themes, his fascinations, wouldn’t change. The song ends with him describing himself as “Just one more who’s searching for / A world that ought to be” — that search would be constant, and if it’d rarely be as depicted as a fantasy as in “The Fountain of Lamneth” or “Xanadu,” it’d still drive many of his songs. And now, with Clockwork Angels, Peart’s come back to that theme, as grand and fantastic as ever.

I should maybe repeat at this point that while I’ve tried to be critical, I love early Rush almost as much as later Rush. Still, with the next album I think Peart’s songwriting would take a giant step forward. There’s a sense in which these early records represent a kind of juvenilia — a writer finding his way, developing symbols, learning what themes matter and what the best ways are to bring them out. The band as a whole was still developing, album to album. Peart, the oldest of them, was only 26 when Hemispheres came out. Most writers would probably be just beginning their career at that age. Peart happened to have already created some of his most famous works. There are advantages and disadvantages to this sort of thing; and the paradox of a rock musician’s career is that, with not quite five albums’s worth of lyrics under his belt (and with Rush as a whole having made half-a-dozen records), the image of who Peart was a writer and who the band were as musicians had become established for many critics and much of their audience. It was an image the band weren’t necessarily concerned with, as future years would show.

More on that this Sunday.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Excellent article! I am a big fan of those first 3 rush albums. I start to lose interest the more they use a synthicizer.

I think Caress of Steel is one of the most underrated albums of all time. The Necromancer has the very definition of a face melting guitar solo.

Maybe I ll have to give some of their later albums a try.

Although I don’t listen to Rush as much these days I’m a card-carrying member of the cult. I loved everything they did up to and including Counterparts, but could never get into their latter work.

I think Caress of Steel does show some immaturity but I love that album more than I ought. Maybe because I was listening to it in my teens/early 20s and could identify with the passions and rages and of Peart’s lyrics, and the feeling of being lost at sea.

I like your mention of heading out into the rain to buy their latest album; I wonder how long with iTunes and so on we’ll be able to have such physical, visceral experiences. Sure beats “Download Now.”

“2112 brought them into the Top 100 for the first time in their career. It was fast, aggressive, furious; maybe faster and more aggressive than any other band up to that point.”

Okay, I’m very fond of 2112. Played many an air guitar solo to it back in the day. But you are not getting away with that statement.

2112 came out in 1976.

Black Sabbath’s first four discs were already out. Zeppelin’s seventh album landed the same year. AC/DC’s third and fourth albums came out that year. Also Blue Oyster Cult’s fifth album, Agents of Fortune. Also UFO’s fifth and sixth disc. Alice Cooper had eight albums out. Scorpion’s fourth landed in 1976. Montrose’s fourth album came out. Thin Lizzy’s sixth and seventh, too. Hawkwind’s seventh. Blue Cheer had six albums available. The Stooges savage first three albums had been available for years. Budgie, Deep Purple, Cream, Mountain, etc. That’s enough.

Ishtar’s eardrums, there’s dozens more, all worth hearing and most worth stacking up next to Rush’s 2112 on the fast-aggressive meter.

It is a fine thing to admire an artist’s work, but use care when heaping those accolades high at the expensive of other artists.

I didn’t quite connect with Rush while I was growing up, so this is a welcome reintroduction. I’ll be giving them another try.

Oh, and I really hope John Hocking writes a character who can exclaim “Ishtar’s eardrums!” with as much conviction as he does. I’ll be smiling at the thought of those divine timpani all afternoon.

Thanks for the good words, all!

John: Some of this may be a function of how one listens to an album, and what a given person reacts to as aggressive. And god knows I won’t claim to have heard everything by all the bands you mention (most of them yes, all, no). Certainly there’s a reason I put “may” in that sentence. But with all those caveats … I dunno. I mean, Sabbath’s heaviness, at least to me, was a function of slow menace more than outright speed. Likewise, Zeppelin could pull out the occasional Immigrant Song, but these days when I listen to them I’m mainly struck by how much of a folk band they are. Blasphemy to classic-rock purists, maybe, but there it is.

I’m kinda just flying by the internet today, though; can we agree to disagree on this one? Barring that, what songs do you recommend? Particularly curious what heavy stuff you hear in early Hawkwind, BOC, and Cream — I like all those bands, but none of them struck me as especially fast or aggressive. (Lemmy’s band when he split off on his own, sure, but early Hawkwind, not as much. And, actually, Wikipedia reminds me that Motorhead was formed in 75, which I’d not realised. So there’s another possible hole in my theory … though the first album doesn’t seem to have come out til 77.)

[…] Arts Award. I’m talking about Rush, and after two posts recapping their career (the first here, the second here), I’ll finally be writing about their new album, Clockwork […]

[…] I therefore begin here in 1980, with the next album, Permanent Waves. (You can find that first post here; the third post, looking closely at the new album, is […]

[…] Clockwork-angels-I-wonders-in-the-world […]