Cerebus

I’ve been writing a fair bit lately about Canadian fantastika, and I’ll be doing so again next week, looking at a trio of grand masters who’ve just released what may be one of the most accomplished works of their career. But there’s been a bit of news lately about another notorious Canadian fantasy epic, so I want to talk about that first.

I’ve been writing a fair bit lately about Canadian fantastika, and I’ll be doing so again next week, looking at a trio of grand masters who’ve just released what may be one of the most accomplished works of their career. But there’s been a bit of news lately about another notorious Canadian fantasy epic, so I want to talk about that first.

Late in May, Dave Sim began a Kickstarter project, trying to raise $6,000 to create a digital version of the 25-issue “High Society” storyline from his comic book Cerebus. He raised the money in a matter of hours. Each comic issue will be digitised; the story, the letter columns, and the editorials will all be scanned (I don’t know whether the work by other cartoonists that Sim used to run in the back of the book will be included). Sim will also read the text of the comic, performing dialogue and captions, and he’ll provide commentary, as well as show and discuss sketches, notebook entries, and the like. The extra money the Kickstarter will raise from this point will go towards higher-quality audio production, and, if funds allow, towards the digitising of the entire 300-issue run of Cerebus. As of June 13, Sim’s raised just shy of $40,000, with the Kickstarter still running for the rest of June.

In light of the Kickstarter success, I want to give a brief introduction to the series for non-comics readers. There’s no doubt that Cerebus was and is a major work, tremendously significant in the history of comics and in the medium’s development. And it’s relevant, I think, as a fantasy story; as a story that sometimes struggles with its use of fantasy, and as a story that works with and often against action-adventure tropes. But while parts of the work are startlingly effective, parts of it are equally-startling misfires. And the main theme of the book, reflecting Sim’s stated beliefs, is undoubtedly sexist (per Merriam-Webster, sexism is “prejudice or discrimination based on sex; especially : discrimination against women”) and in the opinion of many readers misogynistic. Sim disputes the term misogyny, arguing that he’s merely not “feminist,” but when he writes that a sensibility based on “reasoned and coherent world views … occurs more often — far more often — in men than it does in women,” it’s hard to see the difference between that and misogyny. Note that the foregoing statement isn’t an external statement that happens to shed light on Sim’s ideology; it’s a part of the text of Cerebus. Sim’s attitudes to gender and sexuality can’t be evaded in discussing the book. Still, I want to try to present here an overview of what makes the book important, with all its flaws.

Let’s begin at the beginning. The first issue of Cerebus came out late in 1977, written and drawn by Sim, published by him and his then-girlfriend, later wife, Deni Loubert, as Aardvark-Vanaheim Press. That first issue was essentially a parody of Marvel Comics’ Conan series, specifically the early and well-regarded Barry Windsor-Smith run. Sim’s mentioned that he had little interest in Conan as a character, but was interested in Windsor-Smith’s work. At any rate, the title character of Sim’s book was a violent, barbaric warrior hero — who was also a four-foot tall anthropomophic talking grey aardvark. The art was crude, but not uninteresting. There were several good gags; a story obviously derived by “The Tower of the Elephant” (adopted by Windsor-Smith and scripter Roy Thomas for Marvel); a decent twist ending; and a few nice storytelling touches, including a dramatic swordfight in darkness against a skeleton. A good book, but not especially ambitious. Sim later said that he did a lot of his work on the early Cerebus while stoned, and after reading the first issue that doesn’t come as any real surprise.

Let’s begin at the beginning. The first issue of Cerebus came out late in 1977, written and drawn by Sim, published by him and his then-girlfriend, later wife, Deni Loubert, as Aardvark-Vanaheim Press. That first issue was essentially a parody of Marvel Comics’ Conan series, specifically the early and well-regarded Barry Windsor-Smith run. Sim’s mentioned that he had little interest in Conan as a character, but was interested in Windsor-Smith’s work. At any rate, the title character of Sim’s book was a violent, barbaric warrior hero — who was also a four-foot tall anthropomophic talking grey aardvark. The art was crude, but not uninteresting. There were several good gags; a story obviously derived by “The Tower of the Elephant” (adopted by Windsor-Smith and scripter Roy Thomas for Marvel); a decent twist ending; and a few nice storytelling touches, including a dramatic swordfight in darkness against a skeleton. A good book, but not especially ambitious. Sim later said that he did a lot of his work on the early Cerebus while stoned, and after reading the first issue that doesn’t come as any real surprise.

Over the following bimonthly issues, Sim’s craft as an artist, writer, and storyteller developed, if not by leaps and bounds, then at least steadily and consistently. He introduced a number of foils for his barbarian hero: human barbarian chief Bran Mak Mufin; warrior-woman Red Sophia; last king of a dying race Elrod the Albino (who had the speech patterns of Foghorn Leghorn). It was, on the whole, funnier than it sounds. Sim also broadened the world of Estarcion, introducing kingdoms and geography. And he gave Cerebus a love interest, if only for one issue: a dancer named Jaka.

Then, in 1979, after issue 11, something happened.

Sim’s account is here. On the other hand, Sim himself has said that all autobiography is fiction. You can find another take on events here. What seems clear: after taking a large dose of acid, Sim suffered some kind of breakdown, and was institutionalised for a brief time. Sim mentioned in Cerebus that he was diagnosed at this point as “borderline schizophrenic.” In the wake of releasing himself from the hospital, Sim began trying to write about the mental experience in Cerebus. As he says: “When I realized, a month or two later, how large and difficult a task that was going to be, I decided to make Cerebus into a 300-issue project in order to encompass it all and leave room for my own best assessment of the aftermath. The documentation of the state itself went from about issue 20 to about issue 186.”

Sim’s account is here. On the other hand, Sim himself has said that all autobiography is fiction. You can find another take on events here. What seems clear: after taking a large dose of acid, Sim suffered some kind of breakdown, and was institutionalised for a brief time. Sim mentioned in Cerebus that he was diagnosed at this point as “borderline schizophrenic.” In the wake of releasing himself from the hospital, Sim began trying to write about the mental experience in Cerebus. As he says: “When I realized, a month or two later, how large and difficult a task that was going to be, I decided to make Cerebus into a 300-issue project in order to encompass it all and leave room for my own best assessment of the aftermath. The documentation of the state itself went from about issue 20 to about issue 186.”

That quote seems to me to accurately capture something of the nature of the book. Between about issue 11 and issue 20 there’s an increasing development of craft — three- and four-issue storylines, new characters, new situations, increasing accomplishment in rendering and in caricature — and then in 20 there’s a shift away from the story that seemed to be building. That issue, titled “Mind Game,” introduced new power groups, new philosophies, and new storytelling approaches. It took place inside Cerebus’ mind, as the aardvark lay in a stupor, drugged by a sinister fortune-teller; the fortune-teller turns out to be an agent of a matriarchal group called Cirinists, and Cerebus speaks telepathically with them and an “illusionist” named Suenteus Po whose spirit appears to be wandering by. Sim’s panel breakdown, with black and grey backgrounds, was distinctive for a precise reason: assemble all the pages in a vast mural, and you’d see a huge image of Cerebus.

I don’t know how widely-known Sim’s breakdown was among comics professionals. As a reader who came in around 1990, I didn’t hear anything about it until Sim wrote about it years after that. To my recollection, Sim’s attitudes to gender were not widely known among the readership at large for at least the first fifteen years or so of the book’s publication — until issue 186, the other break point Sim mentioned. Important as Sim’s attitudes later became in conditioning the way the book is read, Sim’s structural plan for the work involved not making them explicit until about two thirds of the way through, at which point certain elements of the story were redefined or recontextualised. But then, one of the hallmarks of the story by that point was the way in which it seemed to interrogate and upend all the things it seemed to be establishing, about its characters, about its world, about its themes and structures. (And it is difficult to assess how thoroughly “anti-feminist” Sim’s views were earlier on in the book’s run.)

Before going on with a consideration of the book itself, it’s worth pausing to consider the reception of the book and the retail environment within which it was published. At the time Sim started Cerebus, comics were going through a profound shift in the way they were sold. On the one hand, laws forbidding the selling of drug paraphernalia had led to head shops closing down, cutting off what had been a significant venue for underground comics; on the other, the magazine market had been growing pricier, to the point where low-priced mainstream comics (Marvel, DC, Archie, and so forth) seemed like a poor investment for rack space. At the same time, an increasing market of comics fans had developed an interest in having reliable access to each issue of their preferred titles. The upshot of all this — and it was a far more complicated process than I can describe here — was the development of the direct market: comics specialty stores and dedicated comics distributors.

Before going on with a consideration of the book itself, it’s worth pausing to consider the reception of the book and the retail environment within which it was published. At the time Sim started Cerebus, comics were going through a profound shift in the way they were sold. On the one hand, laws forbidding the selling of drug paraphernalia had led to head shops closing down, cutting off what had been a significant venue for underground comics; on the other, the magazine market had been growing pricier, to the point where low-priced mainstream comics (Marvel, DC, Archie, and so forth) seemed like a poor investment for rack space. At the same time, an increasing market of comics fans had developed an interest in having reliable access to each issue of their preferred titles. The upshot of all this — and it was a far more complicated process than I can describe here — was the development of the direct market: comics specialty stores and dedicated comics distributors.

The emerging direct market was a boon to self-publishers and small publishers as well as to fans. It became possible, at just about the time Cerebus debuted, for an independent comic from a small press to be published and turn a profit. Get your comic into the distributors’ catalogs; get the orders; print your title to fit the orders, and add a bit more for re-orders. Comics sold through comics stores weren’t returnable — if copies on store shelves didn’t sell, the stores had to eat the cost, not the publishers. Cerebus was one of the new titles that thrived in the new retail environment, and conversely also helped that environment to thrive. You couldn’t get “ground-level” comics (not traditional undergrounds, but not straight above-ground books either) like Cerebus or Elfquest or Zot! elsewhere.

(In those early years, Aardvark-Vanaheim published a number of other comics besides Cerebus, including Bob Burden’s bizarre Flaming Carrot and Arn Saba’s wonderfully quirky Neil the Horse. When Loubert separated from Sim in 1984, she took those other titles with her to a new press she founded, Renegade. The point being that Sim was heavily involved in the nascent direct market, as a creator and a publisher.)

The book had gone monthly with issue 14, and effectively kept to a monthly schedule for essentially the rest of its run, up to its conclusion in 2004. Sim’s observed that getting material out on time is immeasurably helpful in building an audience, and Cerebus certainly grew in popularity. When Sim announced, in the editorial matter of issue 19, that Cerebus would be a single story 300 issues long telling his main character’s life story, not many people believed him — but readership increased, and continued to increase as Sim embarked upon what at the time may have been unprecedented in North American comics: a coherent 25-issue storyline.

The book had gone monthly with issue 14, and effectively kept to a monthly schedule for essentially the rest of its run, up to its conclusion in 2004. Sim’s observed that getting material out on time is immeasurably helpful in building an audience, and Cerebus certainly grew in popularity. When Sim announced, in the editorial matter of issue 19, that Cerebus would be a single story 300 issues long telling his main character’s life story, not many people believed him — but readership increased, and continued to increase as Sim embarked upon what at the time may have been unprecedented in North American comics: a coherent 25-issue storyline.

There’d been some examples of long-form storytelling in American comic books, perhaps most notably Marv Wolfman and Gene Colan’s Tomb of Dracula comic. But ToD and similar examples used extended subplots to bind together shorter stories, not an extended serial structure such as Sim had in mind. That story, “High Society,” was a complex political satire, filled with gags, plot twists, and the arcanum of a detailed political system. It was a tremendous success, often considered the book’s high-water mark.

It did, however, take Sim a lot of time to put together. He didn’t quite fall off schedule, but he did find himself taking longer than a month to get each issue out, in part due to his schedule of touring comics conventions. Moreover, he was also finding how much material could fit into a single comics page, and therefore how much would fit into an issue, and therefore also how much would go into two years of a book — and it wasn’t as much as he’d hoped. Originally Sim had wanted to deal with religion in the story that became “High Society,” but there just wasn’t space for it. So with “High Society” completed, he decided to launch an even longer storyline, “Church & State.” Serendipitously enough, the solution to his time crunch happened to come not long after that.

A commercial artist who worked at Sim’s art supply store joined Sim with issue 61, providing detailed backgrounds for the series. With his help, Sim was able to get back on a monthly schedule. That artist, known professionally only as Gerhard, turned out to be exceptionally talented. His work on Cerebus helped establish a distinct, detailed look for the series. His ability to depict architecture and space was stunning, sometimes approaching photorealism. Sim was clearly still the driving force behind the book, but the impact of Gerhard’s backgrounds, the imagination and precision and density, became a strong contributor to the visceral impact of Cerebus’ artwork.

A commercial artist who worked at Sim’s art supply store joined Sim with issue 61, providing detailed backgrounds for the series. With his help, Sim was able to get back on a monthly schedule. That artist, known professionally only as Gerhard, turned out to be exceptionally talented. His work on Cerebus helped establish a distinct, detailed look for the series. His ability to depict architecture and space was stunning, sometimes approaching photorealism. Sim was clearly still the driving force behind the book, but the impact of Gerhard’s backgrounds, the imagination and precision and density, became a strong contributor to the visceral impact of Cerebus’ artwork.

Sim continued to draw the characters, and his skill with caricature continued to develop. By that I mean both his ability to draw exaggerated but recognisable versions of well-known people who, however improbably, turned out to have analogues in Cerebus’ world, and also his ability to capture something of the essence of human personality in stance or facial expression — to say nothing of heightening his character designs to get some point of personality across. At the same time, Sim’s writing was becoming more tighter, more precise, and more evocative. Phrases recurred at meaningful points; foreshadowing grew more prominent. The world grew richer, and the story more complex.

Narratively, after Cerebus is briefly and disastrously elected Prime Minister in “High Society,” “Church & State” finds him swept up in the schemes of the powerful again, ultimately becoming pontiff of a major church. This leads to a literal and metaphorical ascension, which concludes with an extended conversation on the moon with a solemn judicial figure closely modelled on cartoonist Jules Feiffer. As a character, Cerebus had grown and developed all through this process, and not always for the better. Power corrupted him; but the conclusion on the moon upended everything he thought he knew, leaving him returned to earth, all his power again cast down.

Sim was clearly pushing at the bounds of the world he’d made for himself. In fact, the world of Estarcion now was completely different than the Conan-pastiche world of the first few issues. It had developed, socially and technologically, quite quickly, at least up to the edge of industrialisation. There would turn out to be some justification for that, as there was for other moments of surrealism and magic: aardvarks, we’d find out, have a tendency to cause weird things to happen. And Cerebus was not the only talking aardvark in the world.

Sim was clearly pushing at the bounds of the world he’d made for himself. In fact, the world of Estarcion now was completely different than the Conan-pastiche world of the first few issues. It had developed, socially and technologically, quite quickly, at least up to the edge of industrialisation. There would turn out to be some justification for that, as there was for other moments of surrealism and magic: aardvarks, we’d find out, have a tendency to cause weird things to happen. And Cerebus was not the only talking aardvark in the world.

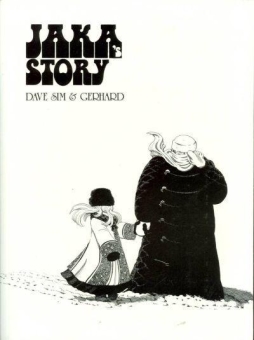

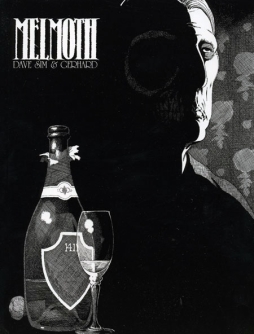

But just as it seemed we were on the edge of an explanation, just as it seemed all the foreshadowing and plot strands were about to pay off in the revelation of some grand design … Sim switched gears. The next two major storylines, “Jaka’s Story” and “Melmoth,” were quiet character-based dramas in which Cerebus was essentially an observer — he spent much of “Melmoth” effectively catatonic. “Jaka’s Story” was a domestic drama about the dancer Cerebus had briefly fallen in love with in an early issue, set against the background of a militaristic matriarchy (the Cirinists that had doped Cerebus back in issue 20) that had taken over in the wake of Cerebus’ ascension to the moon. “Melmoth” was a retelling of the death of Oscar Wilde, set in the world of Estarcion. That sounds like a non-sequitur, but it’s a mark of Sim’s craft that such an improbable idea ended up fitting into the overall architecture of the book, if not seamlessly, then at least for the most part effectively.

By the time “Melmoth” concluded, in 1991, the book had reached issue 150. Most readers had come to accept that Sim was serious about his plans to go to issue 300. Even people who weren’t reading the book had heard of it, and understood the scale of the project. One might argue that by this point in time Sim’s influence on comics wasn’t simply the artistic endeavour of Cerebus, but the means by which that endeavour was being published and sold.

Sim had been self-publishing Cerebus all this time, and had become an ever-more-vocal proponent of self-publishing. Never really a major part of the prose marketplace, self-publishing was far from unusual in comics, going back to Robert Crumb and Zap Comix. Sim argued that it was, in fact, the best form of publishing for those artists who could manage it.

Sim had been self-publishing Cerebus all this time, and had become an ever-more-vocal proponent of self-publishing. Never really a major part of the prose marketplace, self-publishing was far from unusual in comics, going back to Robert Crumb and Zap Comix. Sim argued that it was, in fact, the best form of publishing for those artists who could manage it.

Sim’s experience with self-publishing by this point had taken on many forms, at least one of which was historically significant for comics as a medium. Not long after “High Society” was completed, in 1986, he began producing reprints of the story in a thick trade paperback. The next year, he began reprinting the first twenty-five issue in a companion volume. These “Cerebus phone books,” as they were called, were an early example of trade paperback collections of an ongoing series. At the time, such collections were unusual in North America. Sim’s effort not only helped establish the form of the collected edition, they also (I think) helped cement the perception of the comic as a series of longish stories that worked together to form an overall epic.

As it happened, interest in self-publishing was on the rise in the early 90s, as Sim reached the midpoint of Cerebus. Some of that was spurred by the creation of Image Comics by a number of superstar artists who’d defected from Marvel to make their own company (Sim wrote and drew an early issue of Todd McFarlane’s comic Spawn). Some of it came from the success of Jeff Smith’s comic Bone; some of it simply seemed to be where comics were at in that moment, with works like Colleen Doran’s A Distant Soil, Martin Wagner’s Hepcats, Linda Medley’s Castle Waiting, Steve Bissette’s Tyrant, Gary Spencer Millidge’s Strangehaven, and Larry Marder’s Tales of the Beanworld, among many others. A self-publishing movement developed, with Sim at the forefront. His editorials in Cerebus began to focus on the details of self-publishing: how to go about it, the risks and rewards.

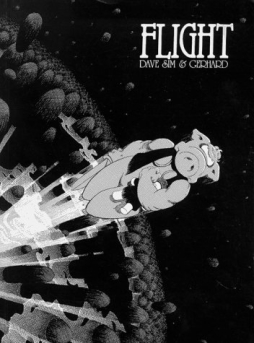

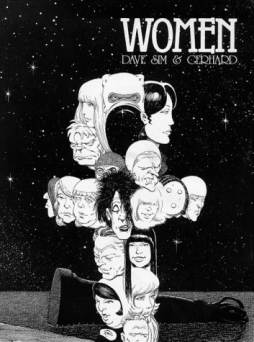

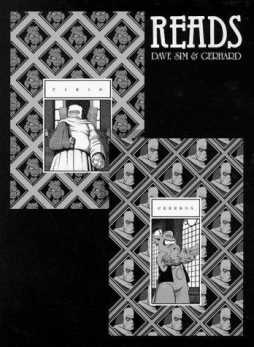

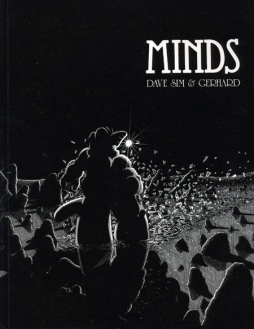

As it happened, the storyline in Cerebus began heating up again at the same time. Cerebus awoke from his stupor, and began to raise a revolt against the matriarchal oppressors. It failed, but by that time another peculiar ascension had begun, involving Cerebus in a battle against Cirin herself, who turned out to be a female aardvark. The new storyline, planned to stretch from issues 151 to 200, was called “Mothers & Daughters,” and sub-divided into “Flight” (151-162), “Women” (163-174), “Reads” (175-186), and “Minds” (187-200). But as it went along, Sim’s treatment of gender became openly troubling. With the end of “Reads” in issue 186, it became clear how extreme his views were.

As it happened, the storyline in Cerebus began heating up again at the same time. Cerebus awoke from his stupor, and began to raise a revolt against the matriarchal oppressors. It failed, but by that time another peculiar ascension had begun, involving Cerebus in a battle against Cirin herself, who turned out to be a female aardvark. The new storyline, planned to stretch from issues 151 to 200, was called “Mothers & Daughters,” and sub-divided into “Flight” (151-162), “Women” (163-174), “Reads” (175-186), and “Minds” (187-200). But as it went along, Sim’s treatment of gender became openly troubling. With the end of “Reads” in issue 186, it became clear how extreme his views were.

As “Reads” had gone on, Sim had interspersed the comics story with a prose narrative, about an unfortunate writer of pulp fiction in the developing Estarcion publishing marketplace. It wasn’t hard to see that Sim was making some satirical points about the comics field. At the same time, it also set up an extended essay that took up most of issue 186, written by Sim in the guise of another pulp writer, Victor Davis (Victor being Sim’s middle name). The essay was an extended meandering tract associating reason with men, emotion with women, and insisting on the natural supremacy of the former — a supremacy, he argued, currently sadly unrecognised by society. Sim specifically rejected the idea of the existence of patriarchy, insisting that “in the Wife and Kids he had found its [power’s] greatest manifestation in human society” and “In a genuine Patriarchy there would be no such thing as marriage.” You can read more extracts here, if you wish; it’s more unpleasant than I’m making it sound.

A lot of people were genuinely shocked by the essay, even though the past couple years of the book had seemed to be increasingly strident in its gender politics and depiction of matriarchy. It may seem odd that a book could run so long, be so profoundly personal, and still have the revelation of one of its major themes be a surprise to so many readers. I think partly that’s because the nature of the theme was so far outside the pale; so extreme. Much of it also is because the book had a habit of upending itself every so often, of seeming to put something forward only to question it later. So the advent of the brutal matriarchy, and the weird parodic writing about gender, seemed like only more of the same. In fact, up to that point, the gender politics of the book had seemed to many readers to tilt the other way. During Cerebus’s first ascension, the revelation given to him on the moon described the creation of the universe in gendered terms from what seemed to be a feminist perspective. As it happened, though, it was actually that perspective which would end up being undermined by the rest of the book.

Broadly, as well, Sim’s depiction of his female characters didn’t align with his description of women in “Reads.” Astoria, one of Cerebus’ political foils, was a canny, hard-headed and Machiavellian thinker. Sim argued in “Reads” that women were rarely formidable artists, that creativity was mainly masculine; but Jaka, the subject of one of the longest extended character studies up to that point, was a creative artist first and foremost. For many readers it was only in retrospect that it became clear that much of “Jaka’s Story” was in fact a story told about her by a male writer (the Oscar Wilde stand-in).

Broadly, as well, Sim’s depiction of his female characters didn’t align with his description of women in “Reads.” Astoria, one of Cerebus’ political foils, was a canny, hard-headed and Machiavellian thinker. Sim argued in “Reads” that women were rarely formidable artists, that creativity was mainly masculine; but Jaka, the subject of one of the longest extended character studies up to that point, was a creative artist first and foremost. For many readers it was only in retrospect that it became clear that much of “Jaka’s Story” was in fact a story told about her by a male writer (the Oscar Wilde stand-in).

That`s certainly not to say it was impossible to see what was happening. Notably, Michael Moorcock wrote to Sim during the “Melmoth” story asking to be removed from Sim’s mailing list, citing the sexism he’d found in Cerebus; Sim printed the letter in issue 147. It was clear by this time that Sim had openly rejected “feminism,” but it wasn’t clear exactly how wide-ranging his definition of “feminism” was, and whether he was rejecting only particularly extreme forms of feminism. But my recollection is of a fair amount of surprise and confusion as Cerebus went through “Mothers & Daughters,” reaching a height after “Reads” concluded. Some people suspected that the tract at the end of “Reads” was another narrative ploy, or a thought experiment; Sim denied this, stating that “Reads” represented his real thinking on gender. There was a fair bit of personal and professional fallout. Sim quarrelled with Jeff Smith, and the self-publishing movement was dealt a setback. Readership dropped.

“Minds,” the conclusion of “Mothers & Daughters,” seemed almost anticlimactic. It was essentially a metafictional wrap-up of the main plot threads of the series. Cerebus met his creator, Dave Sim, and learned that he’d been leading his life the wrong way almost from the start of the run — his big chance to save the world had come in an early issue, almost unnoticed, and he’d thrown it away. It was an oddly facile conclusion; as if Sim had run out of sophisticated narrative techniques, and simply wanted to get the thing done, come what may.

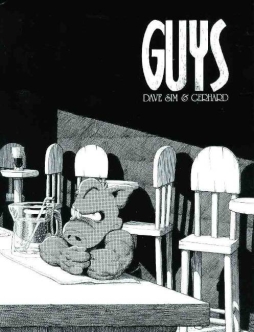

The rest of the run of Cerebus was essentially a long wrap-up. With all the series’ main questions answered, we followed the characters through what remained of their lives. I will readily admit to having read this material only once, and I was largely uninvolved when I did. Cerebus met pastiches of Hemmingway and Fitzgerald, elements which seemed random. There were some good character ideas in the last third of Cerebus, which seemed to me to be unsupported by the narrative of the rest of book. The overall effect is of the overall structure seeming to dissolve into random stretches of comics. Perhaps the worst aspect of this latter section of the book is that it doesn’t ultimately justify the patchy nature of the earlier issues; all the flaws that you thought might lead to a payoff down the road just don’t.

The rest of the run of Cerebus was essentially a long wrap-up. With all the series’ main questions answered, we followed the characters through what remained of their lives. I will readily admit to having read this material only once, and I was largely uninvolved when I did. Cerebus met pastiches of Hemmingway and Fitzgerald, elements which seemed random. There were some good character ideas in the last third of Cerebus, which seemed to me to be unsupported by the narrative of the rest of book. The overall effect is of the overall structure seeming to dissolve into random stretches of comics. Perhaps the worst aspect of this latter section of the book is that it doesn’t ultimately justify the patchy nature of the earlier issues; all the flaws that you thought might lead to a payoff down the road just don’t.

Late in 1996, following research that he undertook for one storyline in the last third of Cerebus, Sim went through a religious conversion, but not to any established religion. Based on his own readings of the Bible and Koran, he formulated his own belief system mixing Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. It didn’t seem to affect his ideas about gender; in 2001 he published a tract in the back of Cerebus called “Tangents,” in which he decried the “feminist-homosexualist axis” he saw as dominating the modern world (you can read the thing here, or just skip to an amusing parody here). But his conversion did seem to shape the ending of the Cerebus storyline; Cerebus founded a religion paralleling Sim’s own, and the last few issues were a close reading of the Bible from Sim’s perspective. Sim abandoned the comics form to present pictures framed by columns of tiny text parsing Bible verses as he understood them, with Cerebus dictating his exegesis of the Bible to a parody of Woody Allen. Finally, the series ended, with a rare mistake in craft (Sim introduced a character meant to be a look-alike for a previous character, but didn’t make it clear that the look-alike was not that character) and an extended melancholy sequence in which an aged Cerebus meets his estranged son, is rejected, dies, and enters the afterlife — to heaven or hell, depending on how the reader interprets it.

In a nutshell, that’s Cerebus. So what does it add up to? Was it worth doing, and was it worth reading?

I can’t entirely answer that. Sim felt it was worth doing, and did it. For years I thought it was worth reading, and gladly read it; and then things changed. I don’t think the last half of the book is much good, and there’s a strong argument that it actually defaults on the promises of much of the first half of the run as well. I think if you’re interested in comics, and especially if you’re seriously interested in the form and the history of the field, Cerebus is essential. If you’re not, I don’t know.

I can’t entirely answer that. Sim felt it was worth doing, and did it. For years I thought it was worth reading, and gladly read it; and then things changed. I don’t think the last half of the book is much good, and there’s a strong argument that it actually defaults on the promises of much of the first half of the run as well. I think if you’re interested in comics, and especially if you’re seriously interested in the form and the history of the field, Cerebus is essential. If you’re not, I don’t know.

Personally, I think there’s much good, much bad, and much that may not have the significance now that it did when the book was published. Sim used the book to comment frequently on the state of comics, and to parody specific comics characters. To non-comics readers, that may be a barrier to accessibility — everybody knows Batman and Spider-Man, and probably a lot of people know Spawn and Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, but considerably fewer know Deadman or Moon Knight. Add to that Sim’s use of real-world characters, either as the focus of long ranging stories (Wilde, Hemingway, Fitzgerald), or as frequent supporting characters (the Marx Brothers, most notably, as well as Woody Allen, Mick Jagger, Keith Richards, and numerous others). Again, some are still well-known. But I don’t know if even Margaret Thatcher’s as significant now as she once appeared, much less Canadian politician Sheila Copps.

Still, for all the caveats, Cerebus is worth looking at — if you don’t mind supporting a man with Sim’s views. Certainly “High Society,” the object of the Kickstarter campaign, is probably the best place to jump in — especially since the rise of manga has somewhat accustomed readers to long-form comics stories. Work backwards to the earlier issues, then forwards for as long as it holds your interest. You’ll find some strong storytelling in there.

More, you’ll find some new ways of thinking about the comics page and how to present material dramatically through comics. Sim’s work, especially in the first hundred or so issues, is often flashy, dazzling with technique. It’s been frequently noted that even his lettering is consistently innovative, playing about with text size and balloon size to communicate emotion graphically as well as through word choice.

More, you’ll find some new ways of thinking about the comics page and how to present material dramatically through comics. Sim’s work, especially in the first hundred or so issues, is often flashy, dazzling with technique. It’s been frequently noted that even his lettering is consistently innovative, playing about with text size and balloon size to communicate emotion graphically as well as through word choice.

I think Sim’s main gift was structural, and I think that played out in three different ways. Firstly, most immediately, he had an incredible knack for timing. That’s a core skill for comics: guiding the readers through the comics page at the rate you want them to read, and communicating the passage of time through panel shapes, lettering placement, and other compositional tricks — while allowing them space and time to react, as readers, to the things the book is showing them. Sim’s handling of time on the page grew more and more sophisticated through the run of the book, and he gained the ability to dissect a moment of action more and more finely. Arguably part of the problem with the later issues came from his drawing those moments out, to the point where narrative and theme seemed to become subordinate to what felt like the self-indulgence of the moment.

Timing, of course, is also key for comedy. So Sim’s undoubted skill at making people laugh reflects his knack for representing time graphically; he knew how to lay out a page, how to position panels, how to cut back and forth, to heighten a funny idea. There’s a reason Sim’s one of those artists of whom people say “I liked his earlier funny work best.”

If timing at the level of the page layout is one aspect of Sim’s structural gift, the second comes in the way he thought about the comic as a unit. The conceit of the “Mind Game” story, building a larger image through the layout of each page, wasn’t a one-off. He’d revisit the “Mind Game” idea, each time in slightly different ways, with a different structural kick. Similarly, he tried any number of different ways to tell a story through comics — in terms of the patterns of panel layouts, in terms of the way text and image were integrated, in terms of the way point-of-view worked graphically and textually. Not all of these ideas worked, but enough of them did often enough that it helped set an odd rhythm for the book as a whole. You expected it to keep showing you new things, to try out new approaches.

If timing at the level of the page layout is one aspect of Sim’s structural gift, the second comes in the way he thought about the comic as a unit. The conceit of the “Mind Game” story, building a larger image through the layout of each page, wasn’t a one-off. He’d revisit the “Mind Game” idea, each time in slightly different ways, with a different structural kick. Similarly, he tried any number of different ways to tell a story through comics — in terms of the patterns of panel layouts, in terms of the way text and image were integrated, in terms of the way point-of-view worked graphically and textually. Not all of these ideas worked, but enough of them did often enough that it helped set an odd rhythm for the book as a whole. You expected it to keep showing you new things, to try out new approaches.

Finally, Sim’s sense of structure played out in the conception of the 300-issue story. What he did was essentially unheard of when he began the project. To see it all the way through, on time, is not only an incredible feat of determination but the product of some clever structural thinking. Sim was able to make the subdivisions of the story work as units in their own right, and as building blocks for the overall tale.

With all that said, and setting Sim’s gender issues to the side for the moment as much as possible, there are also some severe problems with the work. To start with, and perhaps most severely, I don’t think Sim was a good prose writer. As a comics writer, he was excellent; his dialogue, once past his early tyro phase of Conan pastiche, was sharp and tight. But when he allowed himself to write long paragraphs of prose, problems began. His syntax was needlessly convoluted. His paragraphs bristle with parentheses, circumlocutions, and run-on sentences. His attempts at mimicking Wilde in particular are painful. And his attempts at crafting a narrative in prose, specifically during “Reads,” seem to me to be simply lacking craft detail — introducing visual details at an appropriate point, crafting character through words, that sort of thing.

I’ve mentioned that Sim had a considerable knack for structure, and also that the latter half of Cerebus seemed to betray the structural promise of the first half. It became, I think, too diffuse. Sim seemed to be trying to fit in anything that came to hand, regardless of whether it followed conceptually or not. At its best, there was an engaging improvisatory nature to Cerebus promising a satisfactory yet unpredictable resolution; that improvisation seemed to sputter out into incoherence the further the book went along.

I’ve mentioned that Sim had a considerable knack for structure, and also that the latter half of Cerebus seemed to betray the structural promise of the first half. It became, I think, too diffuse. Sim seemed to be trying to fit in anything that came to hand, regardless of whether it followed conceptually or not. At its best, there was an engaging improvisatory nature to Cerebus promising a satisfactory yet unpredictable resolution; that improvisation seemed to sputter out into incoherence the further the book went along.

There’s one school of thought, notably put forward by Comics Journal critic R. Fiore, that Cerebus suffered because Sim was shackled to the 300-issue conceit. Had he simply moved away from Cerebus for a time, had he left the aardvark behind to do comics purely about Wilde, or Hemingway, or whatever was on his mind, the whole might have been better. It’s a reasonable argument, and in the end it may be right. The ambition of trying to fit all these diverse elements into one book was bracing — but the accomplishment was lacking.

Finally, the biggest problem with Cerebus may be the sheer slackness of the last hundred issues. They’re not all bad; some moments are as funny, or as touching, as anything Sim came up with. He had a tremendously funny issue about how bad a hockey team the Toronto Maple Leafs are (as a Montreal Canadiens fan, I greatly appreciated that). And an extended sequence with parodies of the Three Stooges culminates in a surprisingly touching climax. The problem is, to get to that climax, you have to go through the extended sequence. Again and again in the last third of the book, Sim seems to take far too long, and devote too much time and energy, to relatively trivial ends.

It doesn’t help, I suspect, that the shadow of “Reads” hangs over the work at this point in a way I wouldn’t have expected. It’s this: since Sim has explained his view of human nature in great detail, the work which follows seems too clearly to be merely his attempt to illustrate his thesis. It becomes an extended anecdote, bearing out the view of what people are that Sim’s already presented to us didactically. The drama’s undercut, the sense of living character is done away with. The story becomes a dull acting-out-by-rote of what we’ve already been told. This is perhaps also the case in retrospect with the earlier stories. I know that in reading “Jaka’s Story” I initially assumed that one character was meant to be an infantile wastrel freeloader, only to later read Sim identify him as “the nearest I will ever come to a portrayal of a good and thoroughly decent human being.”

It doesn’t help, I suspect, that the shadow of “Reads” hangs over the work at this point in a way I wouldn’t have expected. It’s this: since Sim has explained his view of human nature in great detail, the work which follows seems too clearly to be merely his attempt to illustrate his thesis. It becomes an extended anecdote, bearing out the view of what people are that Sim’s already presented to us didactically. The drama’s undercut, the sense of living character is done away with. The story becomes a dull acting-out-by-rote of what we’ve already been told. This is perhaps also the case in retrospect with the earlier stories. I know that in reading “Jaka’s Story” I initially assumed that one character was meant to be an infantile wastrel freeloader, only to later read Sim identify him as “the nearest I will ever come to a portrayal of a good and thoroughly decent human being.”

(And, it has to be said, those late issues with the Biblical exegesis in tiny print are almost unreadable.)

So let’s say Cerebus is mad and sporadically great, and that the mad often interferes with the great. Could it be otherwise? Sim’s talked about the work coming out of an acid trip and subsequent breakdown. That’s a mental state beyond the norm. Perhaps it was inevitable that something with such an literally irrational genesis should end up being transgressive; perhaps the irrational genesis also led to an opposite reaction, an extreme focus on rationality. I don’t know. I think it’s clear that the sheer work involved in creating 300 monthly comics is tremendous, and the willing assumption of that amount of work is not what most people would consider normal. But motives in the end don’t matter, I suppose. Sim dedicated himself to the work, and the work was done, flawed as it may be in conception and execution. Now it exists as a whole, and presumably will soon exist in digital form.

I think there’s enough good in it that it’s worth looking at. Also enough problems that it’s easy to dismiss. Once I would have been more passionate about the book, for or against. Now I think it’s merely a question of fairness to contextualise it, and let the thing speak for itself. In the end, my assessment of Cerebus is this: it doesn’t continue to involve me, to haunt me. In writing this post I’ve revisited it and reread parts of it; I find it’s stopped growing, that it says nothing more to me now than it did the last time I went through the book, several years ago. Masterpieces don’t do that. Masterpieces always reveal some new facet of themselves when you re-read them. Cerebus, I find, simply is what it is: sporadically involving, occasionally startling, ultimately less than it promises, and its worst moments less unpleasant than simply disappointing. Others will disagree. Having said my piece, I leave the discussion, now, to others.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

As someone who first bought Cerebus with issue 7, it’s great to see this retrospective. I also stopped buying Cerebus long before the end. It was the first comic, for one thing, where I stopped buying the individual issues and waited for the collected volumes to come out; part of the reason was that the glacial pace meant that monthly issues were almost frustrating rather than rewarding, and part of the reason was that Sim’s editorial material and lettercolumns were becoming harder and harder to stomach.

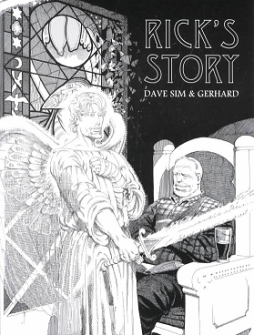

But I still own everything up to “Rick’s Story” and though a lot of it now seems very dated (as you observe, the topical-at-the-time lampoons really have not aged well) it remains a quite remarkable piece of work – it’s borderline “outsider art”, so clearly is it one artist’s personal vision utterly out of step with (despite constantly referencing) everything that contextually lay around it.

And I’m glad you recognise Gerhard’s hugely significant contribution. His work completely changed the texture of the comic, and gave it a depth (in more than just a visual sense) it had previously lacked.

I started reading it in the early 1990’s (although hadn’t Cerebus appeared in a few issues of Marvel’s EPIC or something like that?) and kind of abandoned it sometime around 1995 or 1996 — not because of problems with the title in particular but because I was kind of getting out of comics at that point. I’ve thought about going back and getting the rest of the phonebooks from time to time, but based on this, I’m not so sure.

(And if I’m remembering correctly, the phonebook of Reads was almost unreadable because the text was going too far into the binding — it was fine in a comic book but not so much in a trade paperback.)

Point: “[H]e writes that a sensibility based on ‘reasoned and coherent world views … occurs more often — far more often — in men than it does in women'”.

Counterpoint: “[A]fter taking a large dose of acid, Sim suffered some kind of breakdown”.

Tchernabyelo: Thanks! You stuck with the book longer than I did; I was buying it up through “Reads”, and looked at it in the comics store for a while after that. On the one hand, I didn’t want to support Sim; on the other hand, it was pretty clear he was going to keep doing what he was doing whatever I or other fans did or didn’t do. Honestly, what decided me was that to my mind the quality of the work dropped significantly — “Guys” just seemed tedious, and like you, I stopped entirely with “Rick’s Story.” I borrowed the run a while back to write a piece about it for the Comics Journal, and I remember wondering if those parts would read better as a whole, all in one go. Personally, I didn’t think so.

I’ve actually wondered about Cerebus as outsider art. It does seem to have many of those qualities. But Sim was so much a part of the comics scene the label doesn’t quite fit for me. I think in a technical comics-storytelling sense, a lot of what he did either inspired or played off of other artists. Though that seemed to be less and less true as the book went on through the late 1990s and the 21st century. Can somebody be an outsider artist and still be a part of a community?

Joe H: You remember right; there was a brief run of Cerebus in Marvel’s creator-owned Epic Illustrated. I think that was where Gerhard first started drawing the character. As for picking it up now … if you were reading it into the mid-90s, I believe you’ve probably seen the best of the book. On the other hand, if you haven’t seen the early issues, particularly “High Society,” that’s some pretty good work.

awsnyde: Yup, there’s the contradiction right at the heart of his ideology.

Yes, when I started reading it I ended up getting all of the phone books back to the beginning. I even talked to Sim on the phone once — I called Canada to place an order, and he answered the phone. I was kind of flabbergasted, but we chatted for a few minutes and I recommended a comic book store in Minneapolis as a possible site for a signing. I didn’t make it to that one, but I did meet him in person in Madison, WI, a couple years later. Yes, High Society was a classic, as was Church & State.

Disagree:) and luckily many with better credentials do as well.

And oh look an animated film is being made based on the aardvark’s early adventures

http://www.facebook.com/cerebusfilm

Meaning i disagree with where you say it’s not a masterpiece. A pretty good review otherwise if in a sporadic kinda way:)

[…] Cerebus […]

[…] masterwork Cerebus from time to time here at Black Gate. Matthew David Surridge wrote a splendid piece on the entire series — including the first report of the Kickstarter project — on June […]

[…] Among independent comics, the only one to have surpassed it that I can think of is Dave Sim’s Cerebus, which ended after 300 […]

[…] achievement (the only comparable example I’ve been able to come up with is Dave Sim’s Cerebus). To reach issue 200 under any circumstances is an amazing achievement for an independent […]

[…] both of whom, by the early 1990s, had multiple-volume series either ongoing or already published (Cerebus for Sim, Swamp Thing and From Hell for Moore, to say nothing of Moore’s many single-volume […]