Fiction Review: The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights by John Steinbeck

By Mark Rigney

Copyright © 2008 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

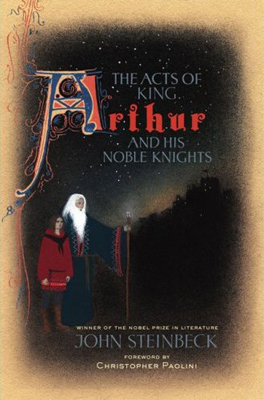

The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights

Viking, 416 pages, hardcover, October 2007 ($29.95)

Let it be known from the outset that my favorite book in all the world remains T. H. White’s The Once and Future King, so it is with some trepidation that I tackle Steinbeck’s equally Arthurian outing, an incomplete project, newly re-issued and with a forward by Christopher Paolini of Eragon fame. With the idea of exploring the morality of might and the practical purposes of power, White set out to humanize Arthur, to explore his boyhood and plumb the psyches of his various knights, Gawaine and Lancelot in particular (also Guenevere), with a post-Freudian awareness of how personal history and the inscrutability of the human mind can snowball into endless complications (read: Tragedy with a capital Aristotelian T). The results are brilliant, a massive and gloriously inconsistent mess, a fantasy of such epic emotional force that it remains to this day the only book I’ve ever had to set down for crying. Tears and books mix nicely, yes, but one cannot, when truly weeping, also read.

Nowadays, as I pass forty and find myself wandering through Philip Roth’s Everyman where I hear that death comes both soon and unexpectedly — that my dying will be unpleasant in every way, essentially cheap, excruciating and in no way ennobling — it seems an excellent moment to revisit the Age of the Quest, with derring-do at every turn, stakes beyond imagining, and a Musketeerish all-for-one-and-one-for-all gestalt. Is this why Steinbeck, too, turned to Arthur as his critical acclaim ebbed and his life wound down? To revivify meaning, to light a candle in that massive future darkness? Steinbeck, referring to the Arthur project, once wrote, “The fact of the matter is that there isn’t enough time in a day to do what I want to do.”

Roth would be sympathetic, for time apparently won. It is telling that the Merriam Webster Encyclopedia of Literature, in the Steinbeck entry, doesn’t even bother to mention Acts. Given Steinbeck’s brilliant career, the critics seem to think that this effort doesn’t even merit a footnote.

Steinbeck’s introduction to Acts tells us point blank that Malory’s Le Morte D’Arthur was the first text to hook him, that if it weren’t for encountering it, the world would never have received such gifts as The Pearl, Of Mice and Men, and that chestnut of high school English class, The Grapes of Wrath. Less clear is Steinbeck’s rationale for returning to his boyhood love — unless it is, as with me, a desire to abnegate Roth’s prognostications and finish one’s days with DVD re-runs of Haley Mills as “glad girl” Pollyanna.

Not that Acts is in any way sunny. Far from it, but its deliberate straightforwardness, due in part to Steinbeck’s desire to modernize Malory’s language, does spare readers the need for a tissue box. The prose at the start remains lofty despite the normalization of the spellings, as distant from the first-person fretting of most current fictions as Pluto is from the sun. In the opening chapters (“Merlin,” “The Knight With the Two Swords,” “The Wedding of King Arthur”) this detached perspective also creates the sense that we are skimming, receiving the historical equivalent of an aerial view. Early on, the newly crowned Arthur heads off to conquer Scotland. Steinbeck, busily anticipating other events, never mentions this campaign again, suggesting not so much an omission as an attitude: The Scottish campaign, while apparently successful, doesn’t matter to the larger tale. Presented merely as a feather in Arthur’s burgeoning cap, it’s immediately time to move on.

The narrative provides as much confusion as enjoyment up until about page one hundred and forty, at which point brothers Gawain and Ewain set off on a quest to prove Ewain’s suspect loyalty. It is at this point that Steinbeck really asserts himself; he shucks off Malory’s yolk and takes charge of the story on his own terms.

Steinbeck’s narrative precision increases yet again when the brothers encounter Sir Marhalt of Ireland (Marhous, in Malory). It’s as if, in Marhalt, a largely forgotten figure, Steinbeck has found the subject he’s been stalking all this time — and indeed, Marhalt is worth following. He is everything Gawain is not: Considerate, contemplative, clever but soft-spoken, skilled but humble. He has but one apparent fault, and that is that he has no concept of how to stop being a knight errant. Settling down is a concept beyond his personal pale, but by the time we discover this, Steinbeck has set Marhalt on such a bonny pedestal that his star cannot easily be dimmed (not even when Ewain’s tutor, Lyne, complains he’s a dullard). Marhalt, far more than Arthur, shines as an example of all that Camelot ought to be.

But then, this has always been the curious position of Arthur within his eponymous canon: To be its most imperfect denizen, its least worthy citizen. Essentially passive, frequently wrong, and given to sudden urges rather than kingly and sober decision-making, Arthur is like the center-point of a wheel from which his best knights relay their adventures — dramas that always take place far away, on the wheel’s outer, faster edges. And yet, without the grounding and gravity of the Arthur the King, all would collapse into forgettable chaos.

Women, as in Malory, tend to get the shaft. That Steinbeck, a writer not specially known for his empowered women, did not choose to improve the lens through which we meet Guenevere, Nyneve, and Igraine (along with an endless parade of damsels in distress) is predictable rather than curious, but in an age where Hilary Clinton has a real shot at the presidency, this failure grates throughout. With a full understanding that these stories are set in another, now inadmissible age, women deserve better treatment. As Nyneve leads Merlin off to his final imprisonment, Steinbeck sees fit to write that “…Nyneve, with the inborn craft of maidens, began to question Merlin about his magic arts, half promising to trade her favors for his knowledge.”

With regards to Nyneve’s “favors,” the delicacy of the various euphemisms for sex are one of the book’s chief’s pleasures. Without once resorting to swearing, Steinbeck, like Malory before him, references all sorts of lusty behaviors. These knights and ladies certainly had no shortage of either beddings or children.

Curiously, the book’s female characters do evolve into specificity starting with Morgan le Fey, who bulls free of generalities simply by being the meanest bitch going. “Hatred,” writes Steinbeck, “was her passion and destruction her pleasure.” Once Morgan enters the fray, a woman’s comeliness ceases to be her defining characteristic. She is followed by Marhalt’s nameless questing companion, who despite her lack of name is every inch a full-blooded character, and after her comes battle-expert Lyne, who molds Ewain into a proper knight errant.

Women have certainly had their Arthurian say in Marion Zimmer Bradley’s The Mists of Avalon, in which the spotlight eschews the men almost entirely, and with great effect. Mists also differs from the Malory/Steinbeck model in its historiography, such that Christianity itself plays a central role. As a new and vital challenge to the druidical and Celtic religions that preceded it, the Christian canon provides the raison d’etre for the Avalon cycle’s power struggles, with Arthur as the centrist attempting (and failing) to assimilate the warring factions of fairy magic and Nazarene carpenter. Steinbeck has no such revisionist ambitions: His knights swear fealty to God before all, and his ladies invoke Jesus at least as readily as their king. (Pellinore’s illegitimate daughter, for example, calls on Christ when cursing her father.) Arthur, handed down through popular Disneyfied memory as a liberal independent, is in fact very much in thrall to the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Steinbeck picks and chooses which adventures to flesh out. With Ewaine’s adventures, what Malory covers in a mere two pages, Steinbeck expands to thirty and more. Malory sees Ewaine ready-made, a knight already; Steinbeck casts him as a boy in desperate need of polish. Quest-obsessed Lyne provides not only a warrior’s training but sharp-witted observation. Under her tutelage, Ewaine witnesses the power of Welsh bowmen and foresees the downfall of knighthood and chivalry. In Ewaine’s voice, Steinbeck writes: “‘If lowborn men could stand up to those born to rule, religion, government, the whole world would fall to pieces.'” Steinbeck allows Lyne to reply: “‘So it would,’ she said. ‘So it will.'”

How long might Acts have been had Steinbeck finished his labors? As the quests gain prominence, Steinbeck lingers longer with each, filling in detail, adding his own opinions with increasing frequency. Malory’s Morte contains twenty-one individual books; Steinbeck makes it only to seven, but at a length of (in this edition) three hundred and sixteen pages. It was not always smooth sailing. Steinbeck writes, in a letter:

You will remember that, being dissatisfied with my own work because it had become glib, I stopped working for over a year in an attempt to allow the glibness to die out, hoping then to start fresh with what might feel to me like a new language. Well, when I started in again it wasn’t a new language at all. It was a pale imitation of the old language only it wasn’t as good because I had grown rusty and the writing muscles were atrophied. So I picked at it and worried at it because I wanted desperately for this work to be the best I had ever done.

And in many places, as when Sir Kay confesses how much he loathes his job as seneschal, or when the four queens tempt Lancelot, the writing is indeed tremendous, of a quality and brand simply unachievable by many of our most popular current fantasists. That said, transitions in the text tend toward the abrupt. In one sequence, Lancelot enjoys an involved dream after escaping an enchanted castle, but because Steinbeck refuses to employ any temporal or grounding signifiers — “Next day” springs to mind, or “upon waking” — the reader has no idea what to make of the sudden arrival of Sir Bagdemagus. Is he also the stuff of which dreams are made, or is he a dawn-clear reality? No doubt a dose or two of gentle, judicious editing would have solved such moments, but that was never to be. As things stand, the reading experience tends to jerk, with the storyteller’s voice shifting from inspired to banal like a plane hitting turbulence.

This awkwardness is due in no small part to the larger, almost tectonic shift in style that comes from attempting the adaptation in the first place, for in updating Malory, Steinbeck must also flex the very forms of fiction. Malory wrote on a mythic level, while Steinbeck, working in an age when realism was king and fabulists were relegated almost entirely to the pulps, wants with all his heart to transform Arthur’s tales into a substance that not only resembles but epitomizes the novel. With mythic work, we hear of action, action, action, as in “and then, and then, and then,” with no respite for contemplation, thematic mood-setting, or philosophic observation. Thus, basic descriptions that twenty-first century readers may take for granted are largely absent in Le Morte D’Arthur, such that a knight will never ponder the drips of sweat that congeal in the small of his back when hot from combat, nor will palfreys whicker in the distance. If whicker they do, that sound will only signify the arrival of a damsel (“damosel,” in Malory) and will not be compared to, say, the laughing of ale-fat peasants.

Such alchemy requires literary flourish, the artifice of the novel. Early on in Steinbeck’s Acts, faithfulness to Malory wins out, but in spurts and starts, beginning, perhaps, with Nyneve’s betrayal of Merlin, the canvas expands and Steinbeck ceases to rely on Malory’s actual sentences for inspiration. Girded with the armor of both modernity and realism, he plunges off on his own — and in a different time, he might well have finished. Why? Because he might have been more comfortable with the idea of writing what has now come to be known as a “fantasy novel.”

Acts, then, remains a project at war with itself. Could it have been any other way?

The presentation of this handsome hardcover bears note. With its dusky picture-frame slipcover and Rachel Sumpter’s flat, folk-arts illustrations, it has the look of a present-tense antique. In the single sweeping appendix, eighty pages long, editor Chase Horton includes a wealth of correspondence between Steinbeck and literary agent Elizabeth Otis, also to Horton himself (as in the quoted selection, above). That these notes exist at all is astounding, and while the general reader may not have reason to plough through the eighty pages devoted to these, aspiring writers (and, one would hope, rising historians) will find a trove of insight into a talented and prolific writer’s process — in this case, a process of defeat.

Steinbeck wrote Acts in 1958 and 1959. He did not continue, and revised only a few sections before his death in 1968. Given his evident enthusiasm for the subject, his failure to complete his Arthurian cycle will forever remain a tantalizing mystery. No matter. Here’s to Sir John Steinbeck of Salinas, California, loyal knight and gentle scribe. May we all be grateful for the gifts of his noble pen.

One thought on “Fiction Review: The Acts of King Arthur and His Noble Knights by John Steinbeck”