When Philip K. Dick Reports You to the FBI: Thomas M. Disch’s Camp Concentration

|

|

Thomas M. Disch is a tragic figure. An enormously talented writer who won the enduring respect of his peers — with nine Nebula nominations and two Hugo nominations to his credit, plus a John W. Campbell Award and Rhysling Award, among many other accolades — his work was long ignored by the public. Success eluded him for virtually his entire career, and he gave up writing almost entirely near the end of his life. After the death of his partner in 2005 he lost his house, fought eviction from his apartment, and eventually killed himself in 2008. In the Science Fiction Encyclopedia John Clute wrote of Disch:

Because of his intellectual audacity, the chillingly distanced mannerism of his narrative art, the austerity of the pleasures he affords, and the fine cruelty of his wit, Disch was perhaps the most respected, least trusted, most envied and least read of all modern sf writers of the first rank.

Certainly his most commercially successful work was the novella “The Brave Little Toaster,” which appeared first in the August 1980 issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction and was nominated for both a Hugo and Nebula. Famed animation director John Lasseter (Toy Story, A Bug’s Life) recalls how he was fired from Disney ten minutes after making a pitch for a film version; Hyperion Pictures eventually produced animated versions of The Brave Little Toaster (1987) and Disch’s sequel, The Brave Little Toaster Goes to Mars (1998).

Perhaps his most successful adult novel was Camp Concentration, which has seen nearly a dozen editions in English since it first appeared in 1968. Alongside On Wings of Song (1979) it’s one of his most acclaimed novels, anyway, and I figure it makes a solid starting point to start reading Disch. It’s interesting for another reason as well — the novel figures prominently in one of the most infamous incidents involving Philip K. Dick, who was so alarmed by Camp Concentration that he wrote a letter to the FBI about it.

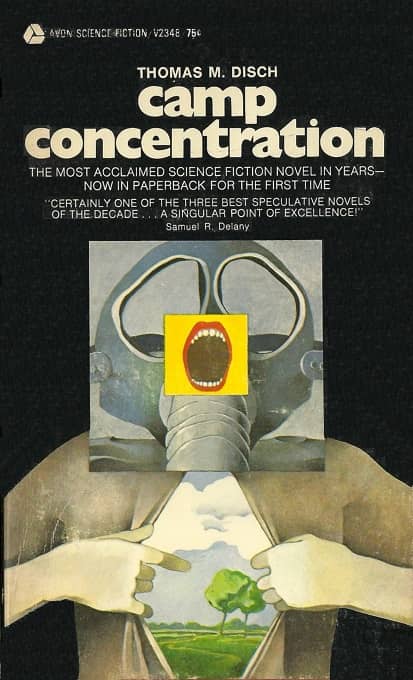

|

|

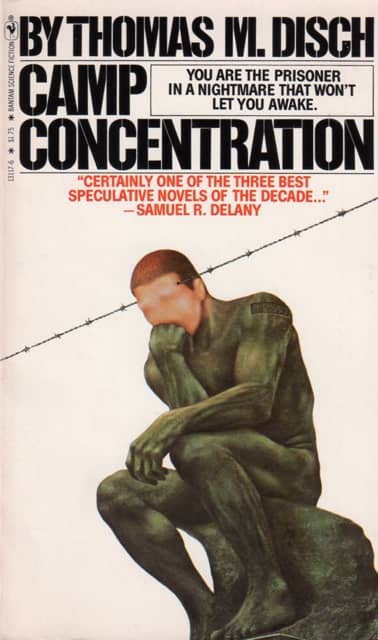

Bantam edition (1980)

The story has been well covered since Dick’s death. The Fortean Times dug up the original letter, and it’s about as wild as you would expect. Here’s a snippet from the article “Philip K. Dick’s FBI File and the Bizarre Neo-Nazi Plot to Trigger the Third World War”:

Undoubtedly, one of the prime reasons why Dick attracted attention from the FBI was a series of bizarre letters he penned to the Bureau in the early 1970s, in which he described his personal knowledge of an alleged underground Nazi cabal that was attempting to covertly manipulate science fiction writers to further advance its hidden cause. And the nature of that cause was even more bizarre: to initiate a Third World War by infecting the American population with syphilis. On 28 October 1972, Dick wrote to the FBI and outlined his distinctly odd beliefs:

“Several months ago I was approached by an individual who I have reason to believe belonged to a covert organization involved in politics, illegal weapons, etc., who put great pressure on me to place coded information in future novels ‘to be read by the right people here and there’, as he phrased it. I refused to do this…

“The reason why I am contacting you about this now is that it now appears that other science fiction writers may have been so approached by other members of this obviously Anti-American organization and may have yielded to the threats and deceitful statements such as were used on me. Therefore I would like to give you any and all information and help I can regarding this, and I ask that your nearest office contact me as soon as possible.

“I stress the urgency of this because within the last three days I have come across a well-distributed science fiction novel which contains in essence the vital material which this individual confronted with me as the basis for encoding. That novel is Camp Concentration by Thomas Disch, which was published by Doubleday & Co.

“P.S. I would like to add: what alarms me the most is that this covert organization which approached me may be Neo-Nazi, although it did not identify itself as being such. My novels are extremely anti-Nazi. I heard only one code identification by this individual: Solarcon-6.”

Disch, who championed Dick and worked tirelessly to get the Philip K. Dick Award off the ground after his death, clearly felt betrayed when he eventually discovered the contents of the letters. Wikipedia has one of the most concise accounts of his elegant revenge:

[Disch’s] first novel, The Genocides, appeared in 1965; Brian W. Aldiss singled it out for praise in a long review in SF Impulse… Writing had become the dominant focus of his life. Disch described his personal transformation from dilettante to “someone who knows what he wants to do and is so busy doing it that he doesn’t have much time for anything else.” After The Genocides, he wrote Camp Concentration and 334. More books followed, including science fiction novels and stories, gothic works, criticism, plays, a libretto for an opera of Frankenstein… In the 1980s, he moved from science fiction to horror with a quartet set in Minneapolis: The Businessman, The M.D., The Priest, and The Sub….

Though Disch was an admirer of and was friends with the author Philip K. Dick, Dick would write an infamous paranoid letter to the FBI in October 1972 that denounced Disch and suggested that there were coded messages, prompted by a covert organization, in Disch’s novel Camp Concentration. Disch was unaware and he would go on to champion the Philip K. Dick Award. In his final novel, however, The Word of God, Disch got his revenge on Dick, with a story in which Dick is dead and living in Hell, unable to write because of writer’s block. In return for a taste of human blood, which will unlock his ability to write, he makes a deal to go back in time and kill Disch’s father, so that Disch will never be born, and at the same time to kill Thomas Mann and thereby to ensure that Hitler wins World War II.

Regardless of Dick’s paranoid assertions (or maybe because of them — who knows?) Camp Concentration has continued to grow in acclaim after Disch’s death. Writing at Conceptual Fiction, Ted Gioia gives us a modern appreciation:

Disch was a visionary — I can’t think of a better word to describe him — and his talents not only extended to the fields of poetry, video games, and film, discussed that day, but many other areas as well… Where does a reader start with such a wide-ranging oeuvre? Disch’s 1968 novel Camp Concentration offers a good entry point, showcasing the storytelling skills that made him a leader of the New Wave movement in sci-fi…

The hero and narrator, Louis Sacchetti is a conscientious objector whose refusal to participate in a Vietnam-type military campaign leads to his internment at Camp Archimedes, an underground government installation involved in secret research. Here prisoners have been injected with a modified version of syphilis that inflames the brain with stirrings of genius. Those infected get smarter with each passing month, demonstrating a remarkable ability to assimilate technical and cultural knowledge. They learn sciences, master new languages, write literary works, and delve into the most arcane reaches of philosophy. But there is an unpleasant side effect: they die from the disease after only nine months. This is their Faustian bargain: they get a taste of the fruits of towering intellect, but at the cost of their lives…

New Wave sci-fi took many chances during this period. Soon after Disch published Camp Concentration, J.G. Ballard released his controversial The Atrocity Exhibition and Samuel R. Delany delivered his daunting Dhalgren. Disch offers a more cohesive work than either these exemplars of experimental sci-fi… the real treat here is in the conversations, some of which remind me of the heated intellectual dialogue in Thomas Mann’s The Magic Mountain, while another powerful section of Camp Concentration offers a modern updating of Dostoevsky’s “The Grand Inquisitor.”..

The best parts of Camp Concentration are captivating in their bravado, smartly conceived and stylishly written… in the current era, when literary fiction and sci-fi are again cross-fertilizing and producing vibrant new hybrids, this 1960s book could serve as a textbook, showing how this merging of highbrow and lowbrow can be achieved, and what heights it can reach.

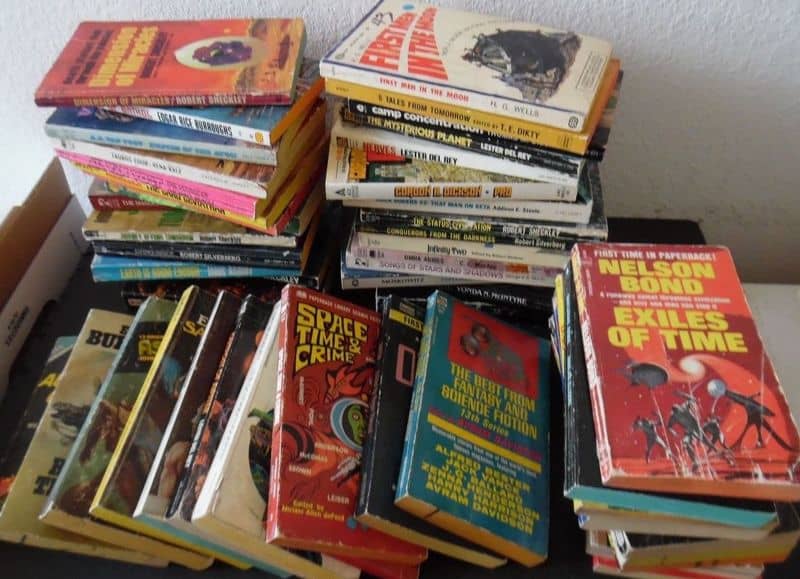

I found Camp Concentration in a box of 50 science fiction paperbacks I bought online five months ago for $23.

My previous exposure to Disch was through his reviews. He was a notoriously cranky and opinionated critic, but his reviews still make entertaining reading today. See a fine example here:

If any of this has piqued your interest in Disch, have a look at Scott Edelman’s epic 18,500-word interview with Disch from 1984, preserved on Scott’s website:

Camp Concentration was serialized in New Worlds Speculative Fiction from July – September 1967, and published in hardcover by Hart-Davis in April 1968. It was reprinted in paperback by Avon in June 1971. It is 175 pages, priced at $0.75. The cover artist is uncredited.

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

It’s a powerful book, certainly, but I felt that the ending didn’t quite “fit.” The conclusion was disconcertingly upbeat considering the unrelieved bleakness of what had gone before.

Disch also wrote an terrific little book that’s a kind of sour overview of the genre, very much in the Malzberg mold – The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of.

Thomas M. Disch wrote ‘The Little Toaster’? This I did not know. I remember getting out the video and enjoying it, and only recently discovered there was a sequel. Weird that – while I know the name well and associate it specifically with SF – I am unfamiliar with Disch’s adult works. Maybe I got to know him via his short stories.

This is a great novel. I agree that the ending comes off a bit upbeat in context. I have heard conflicting stories as to whether that ending was forced on him by his editor, though in fact Disch stands by the ending, and suggests it is misread. (I think maybe the original New Worlds serialization changed the ending, and Disch changed it back.)

Here’s an interview with Disch: https://www.depauw.edu/sfs/interviews/disch29interview.htm

I wonder what Disch meant by saying that the ending was “misread.” If it’s supposed to be a sort of “Owl Creek Bridge” dying man’s fantasy, then I missed that completely, and I was looking for it, simply because the ending seemed so incongruous. I guess I know what I’ll be rereading tonight!

https://www.sfsite.com/07b/drea37.htm