Hercules vs. the Giant Robots

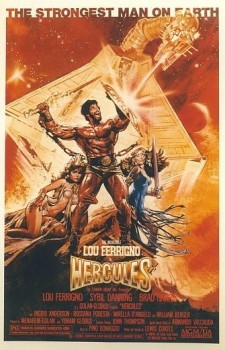

Hercules (1983)Last week I reviewed a silly Conan pastiche novel. Today, I offer a sequel of sorts: a review of a very silly Hercules movie. The 1983 Hercules, sporting former mean, green, grunting machine Lou “Hulk” Ferrigno and the best special effects the Italian film industry can sort of buy, is one of the grandly awful pieces of entertaining oddness ever to come from a Roman studio. And Rome has given us some odd stuff. Aside from sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, the fresh water system, and public health, of course.

Hercules (1983)Last week I reviewed a silly Conan pastiche novel. Today, I offer a sequel of sorts: a review of a very silly Hercules movie. The 1983 Hercules, sporting former mean, green, grunting machine Lou “Hulk” Ferrigno and the best special effects the Italian film industry can sort of buy, is one of the grandly awful pieces of entertaining oddness ever to come from a Roman studio. And Rome has given us some odd stuff. Aside from sanitation, medicine, education, wine, public order, irrigation, roads, the fresh water system, and public health, of course.

I encountered this Hercules when I was eleven years old. I adored Greek mythology since I was in second grade and was well-read in the topic, for which I can thank Clash of the Titans for the initial push. One Friday night, a friend and I watched Hercules when it premiered on cable. It sounded like a sure-winner for kids still not old enough to go out on weekend nights: Greek mythology, monsters, and that guy who played the Hulk. (Plus girls in skimpy outfits, but at eleven we weren’t willing to admit that was already a motivation.)

I’m not certain what I expected from Hercules back then, but it certainly wasn’t what I ended up getting. I had this strange illusion, which only an eleven-year-old can sustain, that a mystical law forced filmmakers to adhere to their source material as closely as they could. When I saw this oddball Hercules film on television, my young boy’s illusions died forever. Which is safer for my sanity, although I still feel the pains from the 1998 Roland Emmerich Godzilla and Jan de Bont’s 1999 demolishing of The Haunting [of Hill House]. The 1983 Hercules has only the most tenuous connection to Greek mythology, and appears like a mishmash of tiny bits and pieces of Hellenic legendary in a goopy stew of trendy science-fiction clichés from the SF-explosion of the late-‘70s. Welcome to Battlestar Hercules. Or perhaps Krull is the most appropriate comparison.

Even though Herc ‘83 was shot in Italy with a native crew, it was produced by the Israeli-born duo of cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, the team behind the US-based Cannon Group that released a slew of Chuck Norris and lesser Charles Bronson action movies during the decade, and occasionally picked up an art-house film like Powaqqatsi. Golan-Globus also killed off the Superman film franchise for almost two decades when Warner Bros. farmed out Superman IV: The Quest for Peace to them. Cannon took care of the US theatrical distribution for Hercules, although the home video rights now belong to MGM/UA.

Even though Herc ‘83 was shot in Italy with a native crew, it was produced by the Israeli-born duo of cousins Menahem Golan and Yoram Globus, the team behind the US-based Cannon Group that released a slew of Chuck Norris and lesser Charles Bronson action movies during the decade, and occasionally picked up an art-house film like Powaqqatsi. Golan-Globus also killed off the Superman film franchise for almost two decades when Warner Bros. farmed out Superman IV: The Quest for Peace to them. Cannon took care of the US theatrical distribution for Hercules, although the home video rights now belong to MGM/UA.

Writer-director Luigi Cozzi claimed in a 1994 interview that it was producer Menahem Golan who first had the idea of doing a new Hercules film because he was a fan of the Italian-made Hercules from 1957 starring Steve Reeves. That movie must have made a financial impression on Golan as well: it turned into an international cash cow in the late ‘50s, and selling international films was Golan-Globus’s specialty. Once Lou Ferrigno, another fellow who was a huge fan of the Steve Reeves Hercules, came onboard as the title character, the movie moved into production. The original director Bruno Mattei had written his own screenplay, but Golan and Globus didn’t like it, and brought on Cozzi to write and direct. It seems that a major shift in focus in the film occurred with the new director, script, and the force of its star.

If we are to believe actress Sybil Danning, the earlier vision of the movie took its foundation from the recent hit Conan the Barbarian and geared toward fantasy. The initial plan for the movie would have it rated “R” and loaded with sex and violence to match the John Milius Conan. Sybil Danning, from a 1992 Starlog interview:

Try to make it through all the nonsense of the script — then think of how good a movie it would have been if Lou Ferrigno and his wife, Carla, hadn’t suddenly turned it into a kiddie film. The original screenplay, an R-rated blend of adventure and erotica, was about how the lonely Hercules wanders around until he finally meets up with a power-hungry, manipulative queen. She sexually seduces him and tricks him into using his strength to conquer other kingdoms. It wraps up when she herself fights Hercules — to the death! The whole reason for doing Hercules was to match the Conan movie and that meant the blood and the guts and the nudity and the sex, but, instead we got a bad episode of Faerie Tale Theater.

Actually, I think we got an episode of the ‘60s Star Trek with Kirk visiting a planet locked in a hi-tech version of ancient Greece. I’m not sure how much Danning’s description matches the original script (the actress notoriously did not get along with Lou Ferrigno on an earlier film and was shifted out of the role of the main love interest in Hercules) but it sounds similar to the Heracles-Omphale myth that formed the basis of the second Steve Reeves Hercules film, 1959’s Hercules Unchained. And we have no proof that this more “erotic” Hercules would have ended up any better than the film we did get. I seriously doubt it. The film we have does stand significantly apart from other Italian copies of Conan the Barbarian simply because it’s so nutsy science-fiction.

Ferrigno physically was an ideal choice to play an Italian movie Hercules, a Steve Reeves successor. I’m a huge fan of Nigel Green’s older, flabbier braggart Hercules in Jason and the Argonauts, which is the closest I think cinema has ever gotten to the Heracles of Greek myth and drama. But in the world of ‘80s cinema, and in a film trying to summon up the ghost of Italian sword-and-sandal films of yore, the Mr. Olympia body-builder-type was the only option, and Ferrigno’s name-recognition was impossible to ignore.

Ferrigno physically was an ideal choice to play an Italian movie Hercules, a Steve Reeves successor. I’m a huge fan of Nigel Green’s older, flabbier braggart Hercules in Jason and the Argonauts, which is the closest I think cinema has ever gotten to the Heracles of Greek myth and drama. But in the world of ‘80s cinema, and in a film trying to summon up the ghost of Italian sword-and-sandal films of yore, the Mr. Olympia body-builder-type was the only option, and Ferrigno’s name-recognition was impossible to ignore.

Interviews Lou Ferrigno gave before the film’s release reveal his intention to make a movie for younger audiences: “Hercules is a film I want all the kids, everybody to go see and not be able to walk out saying, ‘He could have done better.’ I want them to walk out and feel fulfilled,” he told Muscle & Fitness in 1983. “It’s a clean movie.” True; I didn’t see any scratches on the print I viewed.

How strange is the “Greek mythology” in this film? I, swift-running Ryan Harvey of the loud war-cry, will dash over the plot and see if my flashing eyes can spot some differences between the “Heracles legends” and what director Luigi Cozzi and team put up on screen, carrion for birds and wolves. (Okay, I’ll stop with the Homer.)

The planets and the solar system appeared when Pandora’s jar shattered. (What?) The Gods of Greece live on the Moon (huh?) and create Hercules as a way of restoring balance to mankind. He is sent to Earth as the son of the King of Thebes — thus at least getting the location for Heracles correct. King Minos of Thera (come again?) overthrows the King of Thebes, but a maid in the palace pulls a Moses-stunt and sets baby Herc adrift on a river to escape getting murdered. Hera, for reasons never clear, opposes Hercules, and tries to kill the baby with two snake puppets … one of the few instances of accurate Hercules mythology getting into the story. Minos, an adherent of “science” (read: excuse to put more laser blasts into the story) brings a female Daedalus into his world-conquest scheme, and she constructs giant robots to stop the Herc. (Wait … the hell?) Hercules falls in love with Princess Cassiopea (Ingrid Anderson), but Minos kidnaps her as a sacrifice to the Phoenix whom he captured and imprisoned in a volcano in Thera, and which he keeps captive with the Sacred Sword of Thebes that was stolen in an early scene and then conveniently forgotten until the last ten minutes. Sacrificing Cassiopea will allow Minos to … uhm … do something big and apparently wicked. To stop Minos’s sort-of-mad plan, Hercules needs the aid of the sorceress Circe, who got lost from the Odyssey and ended up here. She takes the muscular hero to find an artifact in Hades, which they reach by crossing the Bifröst Bridge (Asgard must have loaned it to the Greeks), and then Hercules separates Africa from Europe so he can get the Chariot of Prometheus from the King of Africa…

There’s no need to further discuss the mythological aspects. Hercules does clean out the Augeian Stables, the only other survivor from the Heracles myth; however, he doesn’t do it as a labor, but to show that he isn’t part of Minos’s general wickedness. No, I don’t understand it either.

I should mention that Thera, “The Black Island,” has a capital called Atlantis — somehow beating out Plato’s invention of the place by a thousand years — and the Colossus of Rhodes straddles its harbor. It is, however, an imaginative looking miniature, even if cheaply produced.

It’s clear what happened here, and why the mythology got swept away like the crud in the Augeian Stables. Star Wars happened. And also the 1978 Superman, which had an enormous effect on the plot of Hercules: infant Herc even gets picked up by a Bronze Age “Jonathan and Martha Kent” when his boat drifts down the river. At age eleven when I first saw the movie I had no idea that Italy had a history of sword-and-sandal mythological and historical adventures, also known as peplum films, but it wouldn’t have helped me if I did since Hercules lurches away from the peplum tradition into science-fiction territory at every opportunity, and even its poster couldn’t have screamed louder about George Lucas if it tried. All that’s left over from sword-and-sandal films are a beefy American bodybuilder, the spaghettini string-budget, a bit of stock footage, and some cheesy action scenes. Hercules overcoming gladiatorial tests to prove himself to the King of Tyre is the nearest the movie comes to traditional peplum, and even here Herc’s sword creates candy-color light bursts when it strikes, and he ends the fight by hurling a log into space. In a climatic scene where Herc breaks free from chains in a dungeon in Thera, he pulls a few classic Steve Reeves stunts like letting guards swarm all over him and then batting them away with one big flex. It’s a pleasantly familiar and silly moment.

It’s clear what happened here, and why the mythology got swept away like the crud in the Augeian Stables. Star Wars happened. And also the 1978 Superman, which had an enormous effect on the plot of Hercules: infant Herc even gets picked up by a Bronze Age “Jonathan and Martha Kent” when his boat drifts down the river. At age eleven when I first saw the movie I had no idea that Italy had a history of sword-and-sandal mythological and historical adventures, also known as peplum films, but it wouldn’t have helped me if I did since Hercules lurches away from the peplum tradition into science-fiction territory at every opportunity, and even its poster couldn’t have screamed louder about George Lucas if it tried. All that’s left over from sword-and-sandal films are a beefy American bodybuilder, the spaghettini string-budget, a bit of stock footage, and some cheesy action scenes. Hercules overcoming gladiatorial tests to prove himself to the King of Tyre is the nearest the movie comes to traditional peplum, and even here Herc’s sword creates candy-color light bursts when it strikes, and he ends the fight by hurling a log into space. In a climatic scene where Herc breaks free from chains in a dungeon in Thera, he pulls a few classic Steve Reeves stunts like letting guards swarm all over him and then batting them away with one big flex. It’s a pleasantly familiar and silly moment.

The plot is merely a loosely-strung series of nonsensical challenges that Hercules has to keep overcoming, perhaps a hand-wave in the direction of the classical “labors,” but more likely just a device to stitch together set-pieces that don’t otherwise fit. Hercules and Circe dash around doing tasks that don’t advance the story until Hercules finally drops in on Thera for the finale.

Even when the science-fiction strivings aren’t manifesting as giant robots, space dioramas examining the planets, and Minos making nonsensical ramblings about the power of science, the film constantly inserts visuals and sound effects meant to give everything a Star Wars sheen. Herc’s fists sometimes create light bursts as they strike, and his climactic battle with Minos occurs with both combatants wielding ersatz lightsabers. The gods and Circe engage their powers with disco-laser shows and tinny electronic sound burps. The sounds effects are extremely annoying; synthesizers in a Bronze Age world simply make no sense, although they are riotously ‘80s.

I’ll give a cheer for composer Pino Donaggio, best known in the U.S. for his work with Brian De Palma. He creates a lush and grand score. It copies the John Williams sound of Star Wars, but since the Star Wars score was itself a throwback to old historical epics, this is one of the recent science-fiction trends that sits well with a sword-and-sandal film. The score would end up recycled in Gor and Outlaw of Gor, two other low budget science-fantasy films from Italy.

The production design is also fun; although the sets look flimsy and cheap, they do exhibit some imagination. Thera’s green and black futuristic appearance is groovy, and Hades and some of the temples are striking even though you know your kid brother could kick them down.

The production design is also fun; although the sets look flimsy and cheap, they do exhibit some imagination. Thera’s green and black futuristic appearance is groovy, and Hades and some of the temples are striking even though you know your kid brother could kick them down.

Most of the optical effects look horrendous, but in an enjoyably risible way — and there’s just no end to ‘em. Most of the visual tricks are flashing balls and sparkly glowing neon lights left over from when disco died. The three stop-motion monsters — a bee-thing, a centaur, and a dragon — show extremely limited movement, and because they’re robots they don’t need fluid motion, but there’s something irresistible about even poorly done stop-motion beasts. The three-headed dragon, a stand-in for the mythological Hydra, is the best of the group. Its three heads don’t move independently, but the action staging in an underground ruin hides some of the flaws and gives a brief sense of awe.

Topping off the hilarity in the VFX, however, are the scenes of Herc hurling an empty bear suit into space and his cosmic journey on a chariot attached to a rock he threw, like, really hard. This is Midnight Movie magic in all its doped-up glory. And I think the filmmakers were serious about it when they did it.

I haven’t mentioned the dialogue yet. This sample, spoken between Minos and his giant robot-making gal-pal Daedalus, provides a good summation:

Daedalus: My little creation should do the trick. My three-headed metal monster will consume Circe and Hercules in its flames.

Minos: Another mechanical monster?

Daedalus: And why not, Minos?

Minos: The last one didn’t work so well, you know.

Daedalus: It spits cosmic rays of deadly fire! Do you know what that means?

Minos: Cosmic rays? That means that … Hercules and Circe will disintegrate!

That’s Ed Wood Jr. genius right there. “It spits cosmic rays of deadly fire!” You know, instead of cosmic rays of non-deadly, soothing fire.

I don’t want to criticize Lou Ferrigno’s performance as the Herc too harshly, because … well, in every interview with him that I’ve read or seen he seems like such a super-nice guy. He also suffers from severe hearing loss that started at age three, which makes his speech difficult to understand, so I can’t hold the decision to dub him with another actor against him. Nonetheless, Ferrigno’s performance is, at best, dull. He’s big and bulky and oiled, as required, but his facial and emotional delivery of already killer-kitsch dialogue is flat; his posture and movements don’t inspire much awe either, as if his constant acting note is “move from here to there.” Each time he gets involved in a tussle, Ferrigno’s face breaks into some odd open-mouthed grimaces, and his Hercules seems to cower from enemies far too often. But the biggest detriment to Ferrigno’s performance isn’t his fault, but that of the dubbed voice that doesn’t fit him at all. The screams of “You witch!” and “Damn you!” are bad-movie comedy gold. I would prefer Ferrigno’s true deep tones, difficult to understand as they might be, than the terrible performance from the dubber. Comprehensibility to a U.S. audience didn’t stop Arnold Schwarzenegger from stardom; the filmmakers should have at least given Lou a fair shake with his distinct voice.

The other performances are perfunctory, and dubbing impairs the minor parts. William Berger, no stranger to acting in Italian films, appears to be enjoying his part of the ludicrous villain Minos, although he probably wonders where his Minotaur and labyrinth have gone. The trio of females leads — Sybil Danning as Adriana, Ingrid Anderson as Cassiopea, and Mirella D’Angelo as Circe — are anonymous except for their looks and the skimpy ‘80s costumes they have to wear. Danning hasn’t much screen time, which is unfortunate since the character has good femme fatale potential.

The really horrendous performances, though, belong to the domain of the Lunar Olympians: Zeus (Claudio Casinelli), Athena (Delia Boccardo), and vaguely antagonistic Hera (Rossana Podestá). These are the most bored and stilted Greek deities you will ever see. Athena, the “Goddess of Wisdom,” is especially awful and played as an airhead. And that frizzed-out ‘80s hairdo sucks the majesty from the goddess. All the gods’ costumes look like they came from a space Christmas pageant done by the local church, with Zeus playing the part of Santa Claus.

The really horrendous performances, though, belong to the domain of the Lunar Olympians: Zeus (Claudio Casinelli), Athena (Delia Boccardo), and vaguely antagonistic Hera (Rossana Podestá). These are the most bored and stilted Greek deities you will ever see. Athena, the “Goddess of Wisdom,” is especially awful and played as an airhead. And that frizzed-out ‘80s hairdo sucks the majesty from the goddess. All the gods’ costumes look like they came from a space Christmas pageant done by the local church, with Zeus playing the part of Santa Claus.

Yes, Hercules ‘83 is a stupendously bad movie. At least it’s never boring.

Hercules received a Great Library of Alexandria ass-whooping from North American critics upon its release. The Houston Chronicle’s review actually makes the film sounds extremely interesting to a certain population: “The values of the film range from massively dumb (the dialogue, by screenwriter Lewis Coates, who also directed), to marginally interesting, such as the special effects (by Armando Valcauda), which occasionally take on the vaguely demented loony feel of Japanese rubber-monster films.” Ah, vaguely demented and Japanese rubber-monster — you have me right there. But I don’t think vaguely covers the dementia on display here at all.

Reactions from current viewers line up with this recent comment on IMDb: “Um……. what the hell?!”

Hercules was successful enough (internationally, at least) to fund a Lou Ferrigno and Luigi Cozzi sequel two years later, The Adventures of Hercules. It’s on the second side of the DVD containing Hercules, but I really don’t want to deal with it now. The effects got worse, the mythology didn’t get a bit better — I’ll leave it at that.

It would be a pleasant surprise if one day a filmmaker tried to deal with the genuine legends of Heracles/Hercules and his fascinating character, such as the figure in the play Alcestis by Euripides. So far, the only film appearance that seems to hint at this figure is Nigel Green’s Hercules in Jason and the Argonauts, and he’s only a supporting character. It’s still possible that some screenwriter or director will come along and unlock the actual mythic power of Heracles. And manage it without laser-lights shows.

Ryan Harvey (RyanHarveyAuthor.com) is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate and has written for the site for over a decade. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires.” His stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla.

From the looks of it, you’ve been mucking out some stables yourself, Ryan.

I may have to subject myself to this one day — I’m surprised I somehow missed it when I was a kid renting every Harryhausen and Spaghetti & Sandal epic I could find.

I don’t know, Bill… perhaps Athena, goddess of wisdom and quality entertainment, steered your young hand away from this one.

(She apparently wasn’t watching over me so closely. I think she’d be enraged at the actress playing her…especially the hair-do!)

I suppose that means I owe her an oxe or two in gratitude.

[…] the phrase “Hercules vs. the Giant Robots” is search engine gold. I still have no idea why my review of the awful Lou Ferrigno Hercules movie has become one of the mainstays of the website, getting in the top ten most popular posts list […]

[…] movies as a long-delayed follow-up to the most popular post I’ve ever done at Black Gate, a joking review of the 1983 Hercules starring Lou Ferrigno. But right as I was planning to explore Hercules in the Haunted World, a piece of important movie […]

[…] My most popular review that I’ve written for Black Gate takes on one of the goofiest fantasy films of the ‘80s, the Lou Ferrigno Hercules. Two-and-a-half years later, I feel I should give the on-screen Hercules another shot with one of the better films to carry his name. Plus, I just pondered the news that a new Hercules film is on the way. Or maybe I’m just trying to repeat the search-engine magic of the name “Hercules.” So let’s leap back twenty-two years from the science-fiction cheesy glitz of Ferrigno’s film and take a kaleidoscopic trip to Hell on a shoestring budget with Mario Bava. […]

[…] Review: Black Gate […]

[…] Review: Black Gate […]

[…] Review: Black Gate […]