The Courage of the Question: Tuck Everlasting

If you have children at home, you know their propensity for asking questions. “Can I have some more?” “Why not?” “Are we there yet?” “Do I have to?” These questions and many others are familiar to everyone who deals with children, and they (the questions, that is) usually don’t pose much of a problem. (In my house, we have long had a standard reply to this kind of query, taken from a Ring Lardner short story: “Shut up, he explained.”)

If you have children at home, you know their propensity for asking questions. “Can I have some more?” “Why not?” “Are we there yet?” “Do I have to?” These questions and many others are familiar to everyone who deals with children, and they (the questions, that is) usually don’t pose much of a problem. (In my house, we have long had a standard reply to this kind of query, taken from a Ring Lardner short story: “Shut up, he explained.”)

Not all childish questions are so easily disposed of, however. The hard ones can range from the mathematical, such as “What if there was no such thing as five?” to the epistemological, like “How do you know?” The roughest ones are literally life and death: “Why did my puppy, why did my friend, why did my Grandpa have to die?” When faced with these, too often the adult impulse is to brush the child off with a pat answer that answers nothing, or better yet, to quickly change the subject.

Tough questions don’t cease to be questions, though, just because we grow too experienced, too jaded, too busy, too complacent, too disappointed, too bored — too old to be willing to ask them ourselves.

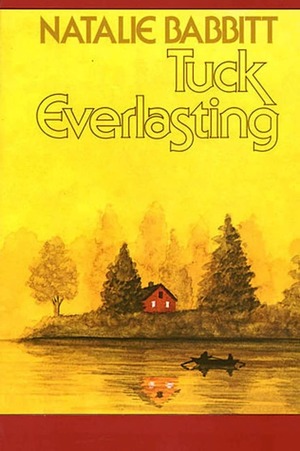

This is one of the reasons children can keep you feeling young… when they’re not making you feel ancient. It’s also why reading great children’s literature can be such a wonderful, renewing experience; such books are addressed to an audience that hasn’t yet gotten into the fatal habit of thinking that all questions have either already been answered or are unanswerable. Such books are themselves like fearless, inquisitive children; they’re willing to speak their minds, whatever the consequences. Books like this are assured of long lives…books like Natalie Babbitt’s 1975 children’s fantasy, Tuck Everlasting.

In the little town of Treegap, in the first week of August in the year 1880, ten year old Winnie Foster feels like life’s possibilities have already dried up. Her overprotective family won’t let her roam, won’t let her experience all that she wants to; her world is cruelly circumscribed by the white picket fence that keeps her safely penned in her front yard. Before the hot August days are over, though, Winnie will have an encounter that will change her life forever, and she’ll be faced with a momentous and irrevocable choice.

One morning, defying her parents’ prohibitions, Winnie slips out of her yard and runs into a nearby wood that her family owns. It is only a few acres in extent, the sole remaining fragment of what was once a mighty forest. She has never gone into it before, and has a vague notion of running away. Before she knows it, she is standing in a little clearing, hidden in the center of the surrounding trees. She sees two things there — a single, enormous tree with a small spring seeping from its base, and a young man. He’s drinking from the spring, which he has uncovered by shifting aside the stones that usually conceal it. At first he doesn’t realize that Winnie is there, watching him; when he does become aware of her presence, he stands and silently looks at her. As their eyes meet, Winnie instantly loses her heart to him; he is the most beautiful person she has ever seen. He appears to be seventeen, and he was, once — eighty seven years before. Jesse Tuck is one hundred and four years old… all because of the spring.

Winnie is hot and thirsty, but Jesse warns her against drinking from the hidden spring. The fact that someone else now knows about it seems to frighten him, and while he’s trying to decide what to do, his Mother Mae and his older brother Miles walk into the clearing. When Mae sees Winnie, she shares her son’s dismay, and she quickly decides that Winnie must not return home, not until they have had a chance to take her to Angus, her husband and the father of the boys. He will know what to do, since, as Mae says, “the worst is happening at last.”

So Winnie, who desperately wanted an adventure, finds herself the victim of a very gentle kidnapping. She’s not too afraid, not at first, because the Tucks seem so kind and considerate and apologetic, and there’s something about them that she can’t help but trust, but when they promise to take her back home tomorrow, instead of being comforted, Winnie, who is still a very young child after all, panics at the thought of being away from home overnight and starts to cry. Trying to soothe her, Mae takes out an old music box and plays it for the girl. The melody calms Winnie down and then, as they continue on their way, Jesse tells her why they had to take her, and why he wouldn’t let her quench her thirst in the clearing.

Eighty seven years before, the Tucks, like so many others, had come from the east looking for good land and a place to settle. Passing through the forest near Treegap, they came across a spring in the middle of the woods and stopped to rest a while.

They all drank from the water — Angus and Mae and Miles and Jesse, and even their horse — all except the family cat, which proved to be important later on. Eventually they came out on the far side of the forest and started a farm in a quiet valley. Life was good, and settled, and ordinary. And then they started to realize that something was… wrong? Or just different?

Jesse fell from high out of a tree and landed on his head — and wasn’t hurt at all. Some hunters accidentally shot their horse, mistaking him for a deer. The bullet didn’t seem to bother the animal in the least. Angus was bitten by a poisonous snake, and there were no ill effects. Mae slipped in the kitchen with a knife, but what should have been a very bad cut left not a mark.

But it was not just their imperviousness to injury that disquieted the family; “it was the passage of time that worried them most.” After ten years, after twenty, none of them were growing any older, except for the cat, who alone had not sampled the water of the spring. It had lived a natural span, aging and dying as any normal creature would. It was then that that Tucks realized the spring had changed them, the spring that Angus thinks was left over “from some other plan of the way the world should be… some plan that didn’t work out too good.”

Before the Tucks understood what had happened to them, Miles had married and started his own family, but as his wife and children aged, he stayed twenty two. Eventually, Miles’ wife and all the people around grew afraid, and started to mutter about witchcraft and black magic, and the Tucks left all they knew behind and moved away; they had to. Angus and Mae established a little farm in an isolated area many miles away. Miles and Jesse, being “younger,” were too restless to stay in one place and spent their time wandering. The family would reunite every ten years, to return and drink from the spring, and to make sure it hadn’t been discovered, because if anyone else ever knew about it, it “would have been a disaster so immense that this weary old earth, owned or not to its fiery core, would have trembled on its axis like a beetle on a pin.”

Natalie Babbitt

While Winnie is still pondering this wild tale and wondering whether she can believe it, they arrive at the Tuck farm. There she meets Angus. After hearing what his family has to say about Winnie finding the spring, Angus takes the girl out rowing on a nearby lake, and tells her what it’s like to be immortal. He speaks of the ever-changing, never-resting nature of life, of the lake water becoming clouds, of the clouds sending down rain to fill the rivers, of the rivers running to the sea.

All of life is like that, Angus says, including people. “But never the same ones. Always coming in new, always growing and changing, and always moving on. That’s the way it’s supposed to be. That’s the way it is.” Except for the Tucks. They are, in Angus’ words, “stuck.” In being liberated from death, life for Angus Tuck and his family has become pointless and useless. “If I knowed how to climb back on the wheel, I’d do it in a minute. You can’t have living without dying. So you can’t call it living, what we got. We just are, we just be, like rocks in the road.”

This talk with Angus awakens Winnie to a realization, for the first time in her young life, of her own mortality, and the sudden reality of death appalls and frightens her. Seeing this, Angus makes his most impassioned argument, because the child simply must understand what’s at stake:

Tuck’s voice was rough now, and Winnie, amazed, sat rigid. No one had ever talked to her of things like this before. “I want to grow again,” he said fiercely, “and change. And if that means I got to move on at the end of it, then I want that, too. Listen, Winnie, it’s something you don’t find out how you feel until afterwards. If people knowed about the spring down there in Treegap, they’d all come running like pigs to slops. They’d trample each other, trying to get some of that water. That’d be bad enough, but afterwards — can you imagine? All the little ones little forever, all the old ones old forever. Can you picture what that means? Forever? The wheel would keep on going round, the water rolling by to the ocean, but the people would’ve turned into nothing but rocks by the side of the road. ‘Cause they wouldn’t know till after, and then it’d be too late.” He peered at her, and Winnie saw that his face was pinched with the effort of explaining. “Do you see, now, child? Do you understand? Oh, Lord, I just got to make you understand!”

Before Winnie can answer, Miles calls them back — someone has stolen their horse. A man was lurking in the wood. Though he has never met the Tucks, he knows them; Miles’ wife and children had come to live with his family when he was a child, and told many tales about the family that never grew old. The man has spent his adult life searching for them, determined to discover their secret. He saw Mae and the boys taking Winnie, and he heard Jesse’s tale. He has been busy in the hours since. He has gone to Winnie’s family and made a bargain with them. In return for the deed to the woods, he will lead the authorities to the place where he knows the child is being held. Winnie’s family agrees, and the man rides with the constable to the Tucks’ farm. On the way, he purposely loses the officer in the woods. He wants some time alone with the Tucks first.

When he arrives at the family’s farm, the man offers to take them on as partners — he will sell the spring water, which he now owns, and they will be living proof of its efficacy. The Tucks angrily refuse and Mae, knowing that this scheme must be stopped at all costs, struggles with their visitor. Just as the constable arrives, the man is accidentally struck over the head and his skull is fractured. Mae is arrested, and when the man dies, she is sentenced to death by hanging.

But Mae Tuck cannot be killed by any rope. So far as she knows, nothing can prevent her from living until the end of the world. To avert the disaster that would ensue from the unsuccessful execution and the questions and revelations that would follow, the Tucks — with Winnie’s help — break Mae out of the jail and leave the area, knowing that Winnie can now be trusted to keep their secret.

Before they go, though, Jesse, hoping for a release from his eternal loneliness, gives Winnie a bottle of the spring water. He tells her to drink it when she is seventeen. They can then find each other and get married, for he has fallen in love with her as she has fallen in love with him.

In the weeks after the Tucks disappear, Winnie considers her choice without coming to any decision. One day she sees a dog menacing a toad that she has often seen around her yard. She thwarts the dog by bringing the toad inside the fence and then, impulsively, she fetches Jesse’s bottle and pours it over the uncomprehending creature:

The little bottle was empty now. It lay on the grass at Winnie’s feet. But if all of it was true, there was more water in the wood. There was plenty more. Just in case. When she was seventeen. If she should decide, there was more water in the wood. Winnie smiled. Then she stooped and put her hand through the fence and set the toad free. “There!” she said. “You’re safe. Forever.”

Seventy years later, Angus and Mae return to Treegap, which has grown and changed beyond recognition. Gone is the little village they knew. Gone too (gone forever) is the wood with its clearing and tree and magic spring. The tree had been struck by lightening a few years before, and the ground had been bulldozed up. While Mae waits in a cafe, Angus walks down to the cemetery. There is something he must check on, even though, as he tells Mae, Jesse “knowed she wasn’t coming. We all knowed that, long time ago.” Once there, he finds a headstone that bears the inscription:

In Loving Memory

Winifred Foster Jackson

Dear Wife

Dear Mother

1870-1948“So,” said Tuck to himself. “Two years. She’s been gone two years.” He stood up and looked around, embarrassed, trying to clear the lump from his throat. But there was no one to see him. The cemetery was very quiet. In the branches of a willow behind him, a red-winged blackbird chirped. Tuck wiped his eyes hastily. Then he straightened his jacket again and drew up his hand in a brief salute. “Good girl,” he said aloud. And then he turned and left the cemetery, walking quickly.

So Winnie made her choice — she gave up the seemingly boundless possibilities of forever for the limitations of a particular life, for the confining love and the inevitable pain that she shared with the husband and children who remained nameless on her headstone, but who were more than everything to her.

On the way out of town, (“No need to come back here no more,” Mae says), they almost run over a toad that’s sitting blithely in the middle of the road, as if it doesn’t have a care in the world. “Damn fool thing must think it’s going to live forever,” Angus says to his wife, as they leave Treegap for whatever it is that forever holds for them.

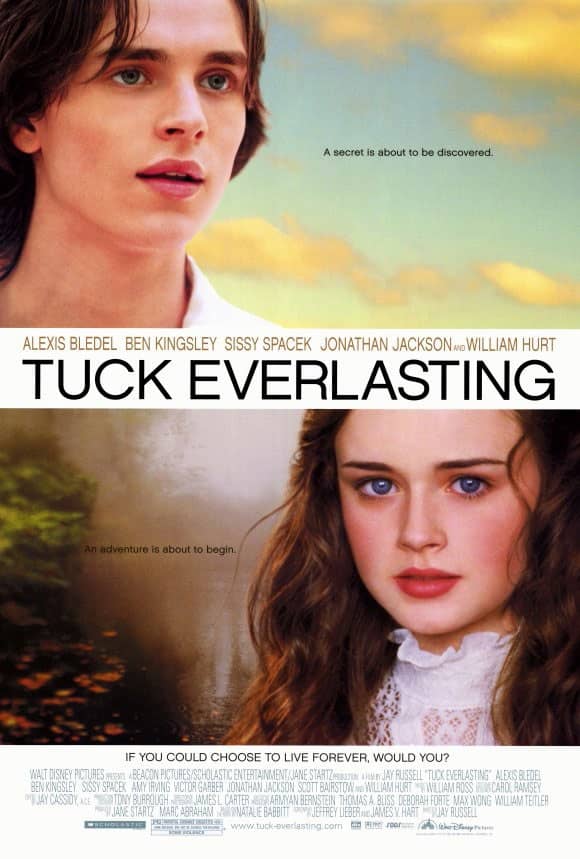

Tuck Everlasting (which was made into a fine and faithful film in 2002) is so deeply felt, perfectly imagined, and gorgeously written that it easily transcends the category of children’s fiction. It is quite simply a great fantasy novel, full of the kind of beauty and wonder that fantasy is best suited to give us, and the quiet truth and wisdom that fill its pages are rare in any genre.

In our era of “transhumanist” ambitions and technological triumphalism (ensured immortality by downloading your consciousness yet?), Babbitt’s book poses questions that many may see as old-fashioned, pointless, and even downright reactionary. Salesmanship and truth are two different things, however, and publicity has nothing to do with pertinence. The most valuable voices are often those which push against the tide of the times, and like the child who discomfits the grown-ups with questions that no one wants raised, Tuck Everlasting feels free to ask why there are limits in life, or to life. Is it possible that by rejecting the notion that life does have boundaries, we’re unwittingly imperiling the very things that give life meaning, things like deep attachments to particular places and people, attachments that are all the more precious because we know how transitory they must be? Might losing — even with the pain it must unavoidably bring — be just as important as gaining? Might there be more wisdom in relinquishing something than in holding onto it? All of which are ways of asking, what is life for, anyway?

It’s a cinch the Elon Musks driving our world today aren’t going to provide any help with such questions, probably because they can’t be answered by collecting and quantifying data, and can have no discernable effect on Tessla’s stock price. But a child or adult who has been fortunate enough to read Natalie Babbitt’s humane and moving book will have been prompted to take these questions seriously and ponder them deeply. As for the answers, each reader will have to provide them for him or herself, just as Winnie did. But the vision to see the questions and the courage to ask them always come first.

Natalie Babbitt died not long ago, on October 31st, 2016, at the age of eighty four. Her life was a long and productive one. She left behind a family and a legacy, the chief monument of which is the miraculous Tuck Everlasting, which shows that though our lives come to an end, the struggles, the passions, the joys, the commitments, and the choices that fill our limited days can continue to reverberate in the hearts of those who come after. A life ends; life continues. Both facts are equally momentous, equally mysterious, equally frightening, equally beautiful. Natalie’s book will always remind us of that.

Good girl.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of Trilogy of Terror.