The Mighty Electric Men

“This man is a Samson in physical strength – in fact, the limit of his strength is unknown even to me., as every bone and muscle in him is of the finest steel. The machinery that works his limbs is inside of him, and he can walk, run, jump, and kick forward or backward with wonderful agility. The motive power that moves him is in a powerful electric battery enclosed in yonder box, under the floor of the carriage, and is communicated to him through wires inside the shafts. … By pressing one knob inside the carriage, there, I start the battery under the floor, and the man shows signs of light and life. That globe inside the helmet gives forth a light that equals the noonday sun, and his eyes do the same. At will I can extinguish all the lights, or only one at a time, just as I may elect. Then another knob starts him going, and another will turn him to the right and another to the left – just as a faithful horse obeys the rein and the bit – and all, too, without my being exposed to any danger from without.”

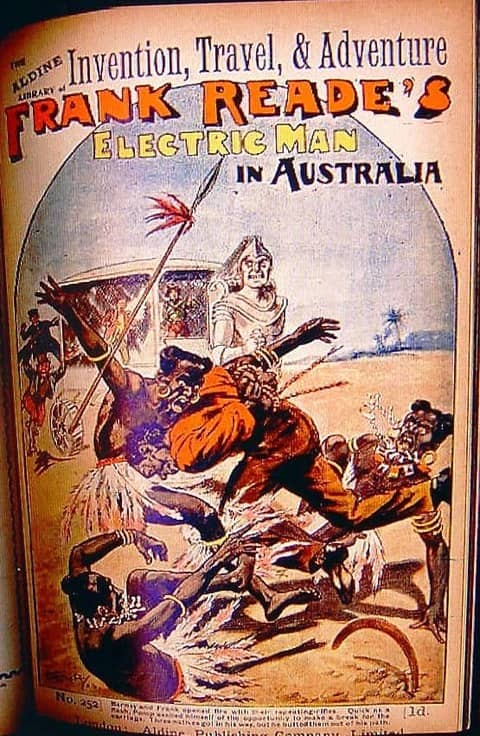

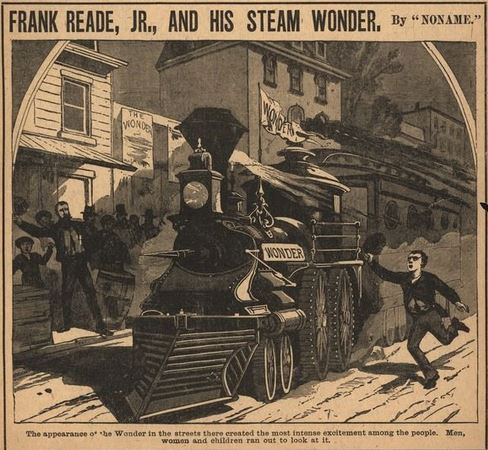

We think of robots being fairly modern marvels, but that’s definitely a description of a robot and it dates to October 10, 1886. The Electric Man in Australia (the fantastically racist cover is from a later London magazine reprint, and yes, those are supposed to be Australian aborigines) was the invention of Frank Reade, Jr., a young inventor who was the prototype for Tom Swift and all his ilk. The adventures of young Frank – there had been a Frank Sr. for four books, with Harry Enton disguised as “Noname” – were written by the amazingly prolific “Noname,” really Luis Senarens, himself a teenager when the first Frank Reade, Jr. book, Frank Reade Jr. and His Steam Wonder, appeared in 1882 in Frank Tousey’s Boys Weekly. A “boys weekly” became a generic term for 8, 16, or 32 page weekly newsprint magazines. For a nickel, later a dime, readers got an exciting illustration on the front page, with the others crammed full of tiny type adventure or mystery novels or stories, sometimes serialized, sometimes filling an entire issue. Dozens of them appeared in the late 19th century only to be superseded by the coming of the pulp magazines.

The world changed so quickly that a mere four years later steam men were old-fashioned, yesterday’s gadgets. Electric men were the new thing, cleaner, stronger, more capable than steam men, seen as the perfect vehicle for bringing the literal light of civilization to benighted and superstitious savages.

Just as the steam men of Frank Reade and his son were blatant ripoffs of earlier writers’ work – Edward Sylvester Ellis introduced them in 1868 in The Steam Man of the Prairies, number 45 in Beadle’s American Novels dime novel series – lesser writers jumped on the Electric Man bandwagon.

William A. King, writing under the name S. G. Lansing, but later adding on a self-anointed lieutenancy, has a half dozen titles credited to him, a good month for Senarens. He was better known for westerns, but had a Vernian touch as well. Josh’s Boy Pards; or, The Mysterious Sky Ranger. A Tale of the Black Hills appeared in 1888 with a thrilling blurb.

A fantastic tale of a flying machine which, by electric batteries, overcomes gravity. Three boys aloft, apparently with ease, carry between them $150,000 worth of gold (500 pounds). Over a hundred Indians killed in 32 pages! A volcanic eruption in the Black Hills!!

When the thrill of killing hordes of Indians palled, he returned to electricity for The Electric Man of the Gold Cavern; or, Big Steve’s Arizona Allies in 1895.

Steve Jackson, bounty hunter and big man, encounters Billy the Kid. They wind up in a mine when Steve suddenly disappears through sold rock. A sepulchral voice intones, “Puny mortals, dare ye invade my regions?”

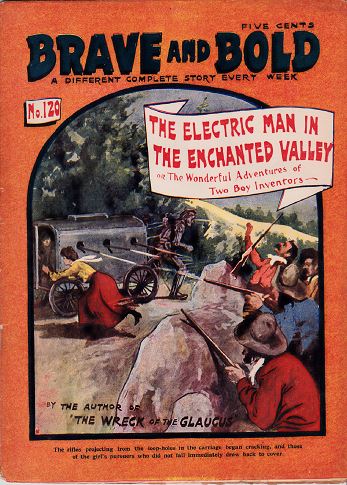

Cornelius Shea is another writer who sublimated a dull background – he was a tobacconist – into exciting escapist adventures. Starting in 1890 he did a series of proto-science fiction tales for the Golden Hours story paper, all later reprinted in the boys weekly Brave and Bold. Unlike Lansing, he’s famous enough to merit an entry in The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Bleiler’s Science Fiction: The Early Years. His The Wonderful Electric Man; or, The Mysteries of the Enchanted Valley, from 1899 was reprinted as The Electric Man in the Enchanted Valley; Or, the Wonderful Adventures of Two Boy Inventors in 1905.

Bleiler provides a handy description because I can’t find online text of the novel.

Young Lake Harwood and Joe Clifton of New Jersey [also the home of other boy inventors like Frank Reade, Jr. and Tom Edison, Jr.] … have already constructed a very efficient electric carriage when they get the idea of increasing its speed by attaching it to an electric man. … The result is a vehicle that under optimal condition can travel at one hundred miles an hour. [Frank Reade, Jr’s could only go fifty.]

As in the earlier stories, they travel west, battle many brown-skinned people, and even get trapped in a cave. Shea also throws in magic and the oddest “lost race” in fiction.

Reproduction in Eslinora: Men and women live in separate sections of the city until marriage. After marriage, the parents are put to death as soon as a child is born. If no children are born, the married couple is put to death anyway. This is population control with a vengeance!

Electric men weren’t the only devices imbued with electricity in these tales. Every manner of buckboard, carriage, caravan, and train were electrified and so were animals, including horses, mules, a “sea spider,” and – I swear – an ostrich.

Robert Toombs’ first “Electric Bob” adventure was Electric Bob and His White Alligator; or, Hunting for Confederate Treasure in the Mississippi River (New York Five Cent Library, July 22, 1893). Get a good idea and beat it into the ground was the motto of the book-a-weekers. That worked in print for a century. Then we got television.

Steve Carper writes for The Digest Enthusiast; his story “Pity the Poor Dybbuk” appeared in Black Gate 2. Much more on robots and other past future marvels on his website at flyingcarsandfoodpills.com. His last article for us was Robot Lilliput N.P. 5357.

![Electric Bob's Big Black Ostrich New York Five Cent Library [v1 #55, August 26, 1893]](https://www.blackgate.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Electric-Bobs-Big-Black-Ostrich-New-York-Five-Cent-Library-v1-55-August-26-1893.png)

Electric horses, mules, ostriches and other contrivances. What’s not to like? And I can see how with titles like “The Electric Man in the Enchanted Valley” and illustrations showing exciting and dramatic scenes, readers would want to come back for more.

Steve, if you don’t mind, could I just ask you why you refer to the first illustration as “fantastically racist”? Maybe to others it’s as clear as day, but I just don’t see where the racism is. Is it racist because these warriors are meant to be aboriginals but look more like African headhunters? That doesn’t quite seem racist to me. That seems more like a case of “shoddy research” or “somewhat ignorant and ill-constructed sensationalism” to me.

Or is the illustration considered racist simply because these aboriginals are shown in a poor light? That is, looking evil and villainous while battling the white hero? What if instead of evil and villainous-looking aboriginals, they were evil and villainous-looking Nazis or Vikings or Spanish Conquistadors? Would it then automatically mean that it was not a racist cover?

Now, do I think that millions of aboriginals in the Americas, Australia, etc., were killed by whites, at least in part through racist inclinations or a belief in white superiority? Yes, definitely.

I know that “racist” is a term that is very freely bandied about nowadays, but perhaps in at least some cases the terms “bigoted” or “insensitive” or “culturally ignorant” or “in poor taste” or what I wrote in the first paragraph are more applicable, and could this, I wonder, be such an instance with respect to the first illustration?

Commodus, I’m not sure I understand your reluctance to use the word racist. The systemic racism of the boys weeklies reflected the systemic racism of the larger societies. It permeates the texts and was sometimes portrayed on the covers, as in this case. Many terms can be applied to this denigration. I’m comfortable with racist.

Steve, I’d be happy to call it racist if I could first understand why it is racist.

I’m not familiar with 19th-century boys’ weeklies, but I’ll take your word for it that racism permeates the texts. But as for this particular cover, in and of itself, I still do not see how it shows racism, unless it is your contention that villains or antagonists cannot be non-white without it automatically indicating racism.

I’d call racism whenever humans are not depicted as people, but lower caricatured forms. I’m always baffled when racism is not called out as such by name. Why diminish the condemnation by prettifying it? Racist attitudes and racist behaviors are what we are – or should be – fighting. Are those people “bigoted” and “insensitive” and “culturally ignorant”? Very likely. But those stem from the base racism. There’s no getting around this.