Romanticism and Fantasy: Storm and Stress and More

This is the latest in a series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy. You can find prior posts here, here, here, and here. I intend in this series to focus primarily on Romanticism in British literature, but last week I looked at the French experience and the French Revolution, and this week I want to look at German literature, which at this period is closely linked to British writing. The caveats I mentioned last week should be borne in mind; I am not a professional historian or academic, and I do not speak or read German — I’m familiar with a fair amount of this writing, but only in translation.

This is the latest in a series of posts about Romanticism and the development of fantasy. You can find prior posts here, here, here, and here. I intend in this series to focus primarily on Romanticism in British literature, but last week I looked at the French experience and the French Revolution, and this week I want to look at German literature, which at this period is closely linked to British writing. The caveats I mentioned last week should be borne in mind; I am not a professional historian or academic, and I do not speak or read German — I’m familiar with a fair amount of this writing, but only in translation.

The German Romantic experience through to the 1830s is of an order of richness and genius at least equivalent to English Romanticism, and in order to be clear about how it all fits together, it’s probably worthwhile explaining some of the historical background. To begin with, in the middle of the 18th century, Germany wasn’t Germany. There was a vague sense of identity among German-language speakers, but their territory was divided up into 300 different polities of various sizes loosely linked together as the Holy Roman Empire (the obligatory historical joke is: The Holy Roman Empire was neither Holy, nor Roman, nor really much of an Empire). Certain noble and ecclesiastical positions among these states inherited the right to vote for the Imperial succession.

By the 18th century, this arrangement was running out of steam. Many of the states involved were finding their interests lay outside of the Empire — the House of Hanover, for example, had become the ruling family of Britain in 1714, while Austria was ruled by the powerful House of Hapsburg, who not only had effectively taken over the Imperial title but controlled a number of other states across Europe. The Holy Roman Empire in any event had suffered particularly badly in the 30 Years’ War, and arguably never fully recovered. Economically it was behind France and Britain. Three quarters of the population were poorly-educated peasantry. And because of the political division, no one German city had the central signficance of London or Paris — each state tended to be focused around its own capital; Vienna, the capital of Austria, one of the largest and most powerful states, was the closest thing to a central German metropolis. Whereas British and French literatures of the time seem dominated by writers and publishers clustered in their respective imperial capitals, the equivalent German movements developed through networks in many different places. The literary culture of Germany was overall somewhat underdeveloped, though strong traditions of popular drama had emerged, particularly in the form of stories about kings and bandits, and also in puppet-shows based on such tales as Faust (all versions of these Faust stories, incidentally, seem to be ultimately derived from Elizabethan playwright Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus).

Many of the Holy Roman states were in direct competition with each other for land and power. In the Seven Years’ War, for example, Austria, in alliance with France, went to war with Prussia, which found itself strugging to defend its borders against a joint opponent 20 times its size. Incredibly, the Prussian King Frederick II, Frederick the Great, managed to outlast the alliance, and Prussia emerged as a major European power (“Dogs,” Frederick cried to his men once when they quailed in a tough situation, “do you want to live forever?”). Rivalry between Prussia and Austria would continue to dominate ‘German’ politics, but Frederick’s achievement helped to inspire a German nationalism. Frederick, like Maria Theresa of Austria, followed the example of Louis XIV of France, who had developed a state based around the absolutist rule of the monarch. This has a forbidding ring to modern ears, but Prussia developed at this time into a rigorously-adminstered constitutional state, with (at least in theory) freedom of thought and religion, equality before the law, and a ban on torture.

Many of the Holy Roman states were in direct competition with each other for land and power. In the Seven Years’ War, for example, Austria, in alliance with France, went to war with Prussia, which found itself strugging to defend its borders against a joint opponent 20 times its size. Incredibly, the Prussian King Frederick II, Frederick the Great, managed to outlast the alliance, and Prussia emerged as a major European power (“Dogs,” Frederick cried to his men once when they quailed in a tough situation, “do you want to live forever?”). Rivalry between Prussia and Austria would continue to dominate ‘German’ politics, but Frederick’s achievement helped to inspire a German nationalism. Frederick, like Maria Theresa of Austria, followed the example of Louis XIV of France, who had developed a state based around the absolutist rule of the monarch. This has a forbidding ring to modern ears, but Prussia developed at this time into a rigorously-adminstered constitutional state, with (at least in theory) freedom of thought and religion, equality before the law, and a ban on torture.

Prussia continued to grow after Frederick’s time, but all German growth was interrupted by the French Revolution and then the Napoleonic Wars. Napoleon conquered much German territory outright, and came to dominate most of the rest economically. The Holy Roman Empire was swept away, finally suspended in 1806. After Napoleon’s defeat in 1815, the Congress of Vienna — itself largely the work of the Austrian Prince Metternich — created a German Confederation which included parts of Prussia and Austria.

This is all the background to the development of a German identity. At the middle of the 18th century, the German states were culturally dominated by France, a dominance exacerbated by the lack of political unity. When, in 1781, Frederick the Great published a treatise on German literature, then going through a period of significant growth, he wrote it in French (characteristically, Frederick argued that the national language had to be unified, with local dialects eliminated). England and English literature were in a sense a useful counter-balance for early German nationalists; the English were a German people, broadly speaking, and ruled by a German king. It came to be felt that English literature had an element of wildness, spontaneity, and creativity that the French were lacking.

In concrete terms, German literature began taking significant steps forward around the mid-18th century. In 1748, the 24-year-old Friedrich Klopstock began publishing Der Messias (The Messiah), a long epic poem on biblical themes. He continued to write it for decades, not completing the poem until 1773, then rewriting it up through 1799. Klopstock’s poem is spectacular, filled with wars of angels and demons; it’s been called proto-science-fiction. It was hugely meaningful to his audience in the 18th century, helping to spark German literary production, though readers since have found it rough going. In the 18th-century, even the name of the poem came to imply profundity.

In concrete terms, German literature began taking significant steps forward around the mid-18th century. In 1748, the 24-year-old Friedrich Klopstock began publishing Der Messias (The Messiah), a long epic poem on biblical themes. He continued to write it for decades, not completing the poem until 1773, then rewriting it up through 1799. Klopstock’s poem is spectacular, filled with wars of angels and demons; it’s been called proto-science-fiction. It was hugely meaningful to his audience in the 18th century, helping to spark German literary production, though readers since have found it rough going. In the 18th-century, even the name of the poem came to imply profundity.

Over the following years, Gotthold Lessing helped establish a German drama. Johann Joachim Winckelmann, an antiquarian, helped instill a love of Greek art among Germans, setting up an affinity for a certain kind of classicism that would endure through the Romantic era. Somewhat more controversial, because of his very urbanity, was Christoph Wieland, who was the first to translate Shakespeare into German, wrote significant early novels (influenced by Winckelmann’s sense of Greece), and in the 1770s turned to writing Oriental tales and verse romances. Geron der Adlige, in 1777, is the first modern German Arthurian poem. Wieland’s Oberon (1780) consciously draws a connection between contemporary verse and medieval romances; translated into English in 1798, it was a significant influence on English Romanticism, and especially John Keats.

Still, Wieland was considered an urbane, perhaps overly-elegant poet by the up-and-coming generation of writers. Some of his works were burned in 1773 in an oak grove outside Göttingen by students celebrating Klopstock’s birthday. This burning was, in fact, a symptom of a new literary movement being born. It seems to have started with theorists first; in 1761, Johann Georg Hamann published an essay called “Aesthetica in nuce: Eine Rhapsodie in kabbalitscher Prosa” (traditionally translated “Aesthetics in a Nutshell: A Rhapsody in Cabbalistic Prose”). Johann Herder, a teacher in the north of Germany, published a number of significant essays — including 1773’s “Auszug aus einem Briefwechsel über Ossian und die Lieder alter Völker” (“Extract From a Correspondence on Ossian and the Songs of Ancient Peoples) which celebrated folk tales, folk creativity, and especially James MacPherson’s Ossianic poetry, viewed by Herder as a true folk epic. At the time, Celts were believed to be a Germanic people; Ossian, combined with the rediscovery of the Eddas (translated into French in 1756), therefore helped to forge an alternative myth-system for Herder and other German writers.

Herder believed that German writers needed to create a national tradition out of their native folk poetry. He believed this would lead to a political and artisic German Renaissance. Herder’s criticism helped foster a fascination with folk poetry and folk tales, which would be felt particularly strongly in later generations (Herder himself would publish an admirably wide-ranging collection of Volkslieder, folk songs from around the world, in 1778), but which manifested itself in the 1770s as well. Notably, Gottfried August Bürger wrote a ballad called “Lenore” in 1773 (and published it in 1774). It’s an uncanny tale of a young woman waiting for her fiancé, who has gone off to war, to return to her. A figure who appears to be her lover comes to her, and takes her on a terrifying and uncanny night ride. Lenore wants to know why they ride so quickly; “the dead travel fast,” responds the knight. He changes as they go, turning into the figure of death, with a scythe and hourglass. The ride ends at the grave where her real lover’s skeleton lies. The poem was an incredible success, in Germany and across Europe, and was translated into numerous languages, with particular popularity in Britain. It’s been seen as a precursor of the figure of the vampire (“the dead travel fast” was quoted in Dracula), and certainly affected the developing genre of the Gothic tale.

Herder believed that German writers needed to create a national tradition out of their native folk poetry. He believed this would lead to a political and artisic German Renaissance. Herder’s criticism helped foster a fascination with folk poetry and folk tales, which would be felt particularly strongly in later generations (Herder himself would publish an admirably wide-ranging collection of Volkslieder, folk songs from around the world, in 1778), but which manifested itself in the 1770s as well. Notably, Gottfried August Bürger wrote a ballad called “Lenore” in 1773 (and published it in 1774). It’s an uncanny tale of a young woman waiting for her fiancé, who has gone off to war, to return to her. A figure who appears to be her lover comes to her, and takes her on a terrifying and uncanny night ride. Lenore wants to know why they ride so quickly; “the dead travel fast,” responds the knight. He changes as they go, turning into the figure of death, with a scythe and hourglass. The ride ends at the grave where her real lover’s skeleton lies. The poem was an incredible success, in Germany and across Europe, and was translated into numerous languages, with particular popularity in Britain. It’s been seen as a precursor of the figure of the vampire (“the dead travel fast” was quoted in Dracula), and certainly affected the developing genre of the Gothic tale.

In 1770, Herder happened to strike up an acquaintance with a young poet, with whom he discussed writers that had significance for the new literary style Herder saw growing. Rousseau was one important influence, but so was Ossian, along with Homer and Shakespeare — writers who seemed to insist on emotional response, whose work seemed to grow out of a folk culture. The young poet, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, published a Shakespearean historical drama, Götz von Berlichingen, and then in 1774 a short novel about a failed love affair: Die Leiden des jungen Werther (The Sorrows of Young Werther). An extravagant, emotional book, Werther became a European sensation. Fashionable young men dressed in the colours of the main character, read Ossian as he did — and sometimes, just as he did, committed suicide for love.

Radical emotional sentiment; a lively response to nature; perhaps above all, a concern with genius, originality, and towering personalities. These were some of the key ingredients in Werther, and these were elements of the new movement in German writing, which acquired a name from a play written in 1776 about the unfolding American Revolution: Sturm und Drang (Storm and Stress). At the time, Sturm und Drang was seen as a reaction against the German Enlightenment (Aufklärung), though recent scholarship has tended to see it more as a development within Enlightenment traditions. It certainly seems conected with later Romantic writing; the Sturm und Drang insisted on the power of genius, and its ability to overcome the limitations of imposed literary ‘rules.’ Crutches, said Herder, help the sick but hinder the healthy; so rules, in the hands of a bad or mediocre writer, can produce work that is correct but dull, while the genius must ignore the rules to produce the work that genius believes to be important. Genius was like a flood, a thing of immense power that could overturn all accepted norms — and was an implicit threat to the bourgeois social order.

Much has been written on the question of how revolutionary the Sturm und Drang was. Some of its themes seem to harmonise with radicalism; the revolt of sons against fathers, for example (and the Sturm und Drang was notable for the lack of women writers involved in it). But by 1776, when the American Revolution broke out, the movement already seems to have been in decline. German literature was looking healthier than ever — book production doubled between 1764 and 1784, and in 1780 five thousand books were published in German — but Goethe, the most talented of the Sturm und Drang writers, had moved to the small duchy of Weimar, where his writing took a more classical turn. Other writers would follow him, both physically to Weimar and artistically towards classicism. In 1781, a drama called Die Räuber (The Robbers), by a young playwright named Friedrich Schiller, was published, and staged the following year; nominally considered part of the Sturm und Drang, its themes seemed to suggest something else, pointing the way to new developments.

Much has been written on the question of how revolutionary the Sturm und Drang was. Some of its themes seem to harmonise with radicalism; the revolt of sons against fathers, for example (and the Sturm und Drang was notable for the lack of women writers involved in it). But by 1776, when the American Revolution broke out, the movement already seems to have been in decline. German literature was looking healthier than ever — book production doubled between 1764 and 1784, and in 1780 five thousand books were published in German — but Goethe, the most talented of the Sturm und Drang writers, had moved to the small duchy of Weimar, where his writing took a more classical turn. Other writers would follow him, both physically to Weimar and artistically towards classicism. In 1781, a drama called Die Räuber (The Robbers), by a young playwright named Friedrich Schiller, was published, and staged the following year; nominally considered part of the Sturm und Drang, its themes seemed to suggest something else, pointing the way to new developments.

Schiller would produce some significant historical dramas over the 1780s, and then toward the end of the decade began a prose novel, published in installments. He soon grew tired of it, and never finished it, though it was one of his most popular works — and, I feel, immediately relevant to the development of fantasy. Titled Die Geistersehrer (The Ghost-Seer), it followed an unnamed German prince in Venice, who encountered strange and apparently supernatural phenomena — only to have some of those phenomena explained as carefully staged frauds, leading him to doubt the signficance of the rest. The overall plot seems to have had to do with a secret society that had designs against the prince, but the story breaks off before we find out what, exactly, and who the mysterious figure is that seems to be behind the events of the tale.

Personally, I think that had Schiller completed Die Geistersehrer he might have written a masterpiece. It doesn’t feel much like earlier fiction, marrying the new techniques of the realistic novel with extravagant and surreal subject-matter. As it is, it’s a rich fragment that mixes occultists, freemasons, the Inquisition, magic, and illusions with well-observed character-drawing and what seems like a complex plot and structure. In any event, it was tremendously influential, and I have to wonder whether the fragmentary nature of the work didn’t help give it some extra power with its audience — whether creative readers weren’t driven to rewrite it and complete it because it was unfinished.

It is certain that the story had an impact. Popular writers, starting with Charles Spiess, produced prose works mixing the fantastic aspects of Die Geistersehrer with the historical and Shakespearean elements of Götz von Berlichingen, creating not one but three genres of popular fiction: Ritter-, Räuber-, and Schauerromane (novels of chivalry, of banditry, and of terror; a classification devised in 1859 and followed ever since). As the name of one of these genres suggest, Die Räuber had an influence here as well. Not only novels, but popular plays were written in these styles (notably by August von Kotzebue), which also seem to have shown the influence of the German märchen, or fairy tales.

It is certain that the story had an impact. Popular writers, starting with Charles Spiess, produced prose works mixing the fantastic aspects of Die Geistersehrer with the historical and Shakespearean elements of Götz von Berlichingen, creating not one but three genres of popular fiction: Ritter-, Räuber-, and Schauerromane (novels of chivalry, of banditry, and of terror; a classification devised in 1859 and followed ever since). As the name of one of these genres suggest, Die Räuber had an influence here as well. Not only novels, but popular plays were written in these styles (notably by August von Kotzebue), which also seem to have shown the influence of the German märchen, or fairy tales.

It’s tempting to speculate about the links to the French literary fairy tale tradition — and some studies seem to suggest that oral tales may derive from literary works to a greater extent than one would suspect — but there seems no doubt that the Schauerromane in particular entered into a complex relationship of mutual influence with the English Gothic novel. Novels were translated from one language to another, often through an intermediary French translation. Spiess’ 1791 Petermännchen (Literally Little Peter, translated 1792 as The Dwarf of Westerbourg), a tale of two demons competing for a knight’s soul, seems to have been particularly significant, but any number of these works were churned out, part of a burgeoning popular fiction industry.

Schiller himself joined Goethe in Weimar in the mid-90s, following Goethe in his investigation of classical themes. But another generation of writers, influenced by the Sturm und Drang, was emerging with an interest in the ‘romantic’ world — the medieval Christian era, as opposed to the Greek and Roman pagan times — and an interest as well in the novel, the romane. These writers tended to congregate in the town of Jena, around the figures of two brothers, the essayists and editors Friedrich and August Wilhelm Schlegel, along with August Wilhelm’s wife, Caroline Schelling, and Friedrich’s wife, Dorothea Veit (August Wilhelm Schlegel was also a translator of note, whose ten-volume Shakespeare translation, published from 1797 to 1810, still stands as definitive).

These writers, later to be known as Early Romantics, rejected monolithic systems and questioned assumptions. They insisted on individual subjectivity, and the imagination. They were fascinated by altered states, dreams and visions, which they nevertheless believed should be scrutinised with the use of reason. The novel seemed like the ideal form for all these concerns, a new medium that could explore a multitude of themes with a radical freedom of form — a venue in which the creative genius could find his or her own way, and develop sophisticated new structures. In 1798 the Schlegels founded their own journal, the Athenaeum, in order to promote these ideas, “the miraculous eternal alternation of enthusiasm and irony.”

These writers, later to be known as Early Romantics, rejected monolithic systems and questioned assumptions. They insisted on individual subjectivity, and the imagination. They were fascinated by altered states, dreams and visions, which they nevertheless believed should be scrutinised with the use of reason. The novel seemed like the ideal form for all these concerns, a new medium that could explore a multitude of themes with a radical freedom of form — a venue in which the creative genius could find his or her own way, and develop sophisticated new structures. In 1798 the Schlegels founded their own journal, the Athenaeum, in order to promote these ideas, “the miraculous eternal alternation of enthusiasm and irony.”

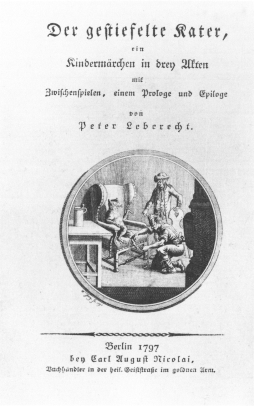

This irony, though, was of a different order than Enlightenment irony. You can perhaps see this is the work of one of the key Early Romantic prose writers. Johann Ludwig Tieck wrote various works through the 1790s — including a horror novel in 1795 (Abdallah) — before moving on to write literary märchen. A collection of these tales appeared in 1797, including plays on Ritter Blaubart (Sir Bluebeard) and Der Gestiefelte Kater (Puss-in-Boots) that used sophisticated structure and fairy tale ideas. Tieck seems to have become fascinated with märchen; after writing some volumes of art and music criticism with his friend Wilhelm Heinrich Wackenroder, insisting on the importance of creative expression and the artistic freedom of genius, Tieck went on to write fairy tales for the next two decades or so, producing a notable collection in Phantasus (published in three volumes between 1812 and 1817).

Whether inspired by French writers or not, Tieck seems to have found a form in German for retellings of old tales, and indeed for the creation of new tales; a form involving a feel for nature (especially the deep dangerous woods), a seeming artlessness, and a language sprinkled with archaisms. In particular, Tieck seems to have had a sense of the emotional effect of horror and the marvellous on his readers, and exploited this in a new and distinctive manner. On the other hand, Tieck has also been seen as less than fully-committed to Romanticism, or more precisely, as inhibited in his fantasy. One critic said that like a cat he slinks “around the one thing that is needful, nibbles, but never risks burning a paw;” Friedrich Schlegel privately described Tieck to his brother as “hollow,” “quite an ordinary and coarse man,” who was “equally thin in spirit and body.” This does not seem to have inhibited Tieck’s popularity among readers at the time, or indeed his influence on later writers.

Also among the Early Romantics in Jena — indeed one of the archetypal Romantic writers — was Friedrich von Hardenberg, frequently known by his pen name, Novalis. Novalis was a writer of mystical verse, best-known for his Hymnen an die Nacht (Hymns to Night). Before his early death in 1801, he also produced an unfinished novel, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, set in the Middle Ages and incorporating poetry, dream-visions, and märchen — indeed the fragmentary latter part of the novel seems to dissolve into fairy tales. The book created a resonant symbol of Romanticism in an early dream sequence: the blue flower (blaue blume), which stands for the striving after the infinite, and inspiration, and love. The novel overall is unfinished, and critics have had difficulty in finding a form implied by what Novalis did produce; but the Romantics were prepared to experiment radically with form, building novels around ‘geometrical progression’ or similar abstract ideas, giving classical critics fits even today.

Also among the Early Romantics in Jena — indeed one of the archetypal Romantic writers — was Friedrich von Hardenberg, frequently known by his pen name, Novalis. Novalis was a writer of mystical verse, best-known for his Hymnen an die Nacht (Hymns to Night). Before his early death in 1801, he also produced an unfinished novel, Heinrich von Ofterdingen, set in the Middle Ages and incorporating poetry, dream-visions, and märchen — indeed the fragmentary latter part of the novel seems to dissolve into fairy tales. The book created a resonant symbol of Romanticism in an early dream sequence: the blue flower (blaue blume), which stands for the striving after the infinite, and inspiration, and love. The novel overall is unfinished, and critics have had difficulty in finding a form implied by what Novalis did produce; but the Romantics were prepared to experiment radically with form, building novels around ‘geometrical progression’ or similar abstract ideas, giving classical critics fits even today.

The Jena Romantic group had broken up by about 1805, but some writers, such as Tieck, continued to produce work, and other writers appeared who were clearly influenced by the Early Romantics. The 24-year-old Karoline von Günderrode published Gedichte und Phantasien (Poems and Fantasies) in 1804, following it a year later with Poetische Fragmente (Poetic Fragments), then committed suicide a year after that. Her work used traditional stories from numerous mythologies, celebrating and interrogating past heroes and contemporary figures — specifically Napoleon.

While the early Romantics had their heyday, Goethe and Schiller were continuing their classically oriented writing. Or so they and most German critics of the past couple hundred years would say. And yet other nations, particularly the English, still perceived them as Romantic; one might say that their project involved unifying the classic and romantic. Or one could say that the complexity of their work precludes easy definitions. At any rate, in 1790 Goethe published a collection of his works which included a fragment of a play on the Faust legend. Schiller encouraged Goethe to work further on it, until Schiller’s early death in 1805, and Goethe eventually published the first part of Faust in 1808.

You can see the outline of the traditional Faust in Goethe’s version, but the tale’s been reworked and given both new depth and new linguistic density. The play begins in heaven, in a scene evoking the Book of Job, in which God gives the diabolical Mephistopheles free reign to tempt the occult scholar Faust, and take him to hell if he can catch him. As the story goes on, we see Faust enter into his bargain, but with a twist. The traditional Faust asked for power during a set period of time, after which he’d give his soul to hell. This Faust makes a bet: he will have power as long as he likes, until he wants to tarry, until he asks time to slow down so that he can enjoy a moment longer. It’s a resonant change, emphasising the striving, energetic nature of Goethe’s character. The sardonic, ironic, and cynical Mephistopheles is equally as memorable, making the play not merely profound and dramatic, but funny. Ultimately this first part of Goethe’s story ends with Faust going to the diabolical festival on the Brocken on Walpurgisnacht (as later celebrated in Modest Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain), and the co-incidental death of a woman he loved but ruined.

You can see the outline of the traditional Faust in Goethe’s version, but the tale’s been reworked and given both new depth and new linguistic density. The play begins in heaven, in a scene evoking the Book of Job, in which God gives the diabolical Mephistopheles free reign to tempt the occult scholar Faust, and take him to hell if he can catch him. As the story goes on, we see Faust enter into his bargain, but with a twist. The traditional Faust asked for power during a set period of time, after which he’d give his soul to hell. This Faust makes a bet: he will have power as long as he likes, until he wants to tarry, until he asks time to slow down so that he can enjoy a moment longer. It’s a resonant change, emphasising the striving, energetic nature of Goethe’s character. The sardonic, ironic, and cynical Mephistopheles is equally as memorable, making the play not merely profound and dramatic, but funny. Ultimately this first part of Goethe’s story ends with Faust going to the diabolical festival on the Brocken on Walpurgisnacht (as later celebrated in Modest Mussorgsky’s Night on Bald Mountain), and the co-incidental death of a woman he loved but ruined.

At about the same time as Faust was being published, the final volume of a remarkable collection of Volkslieder, folk-songs, came out — Das Knaben Wunderhorn: Alte deutsche Lieder (The Youth’s Magic Horn: Old German Songs). It was a collaborative venture by two Romantic writers, Clemens Brentano and Achim von Arnim. Brentano was a poet, novelist, and playwright, whose play Ponce de Leon was based on a plot from a story by Madame d’Aulnoy collected in the Cabinet des Fées. Arnim was a historical novelist and epic poet. They first hatched a plan to collect songs in 1802, and published the collection in three volumes, from 1805 to 1808. The songs aren’t fantastic, instead recalling pre-modern and pre-industrial rhythms of life. But the collection did unintentionally spur the creation of a classic work of fantasy.

Arnim and Brentano didn’t see themselves as scientific curators so much as collaborators with the volk, the people, rewriting and correcting as they saw fit to make the best songs they could imagine. One pair of philologically-inclined brothers who had helped to find songs for them were dissatisfied with the liberal way the poets treated the material. Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm believed that it was important to record the actual traditions and texts of the volk, using philological laws where possible to recover vanished ways, but fundamentally being faithful to the actual recorded words.

Oddly, they didn’t stick to this theory with their own collection of folktales, the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, the first volume of which was published in 1812, with the second following in 1815. They revised their books constantly over the years, in later printings toning down the earthier and more sexual elements (though occasionally increasing the violence) in a successful bid to make a collection aimed at children. They shaped the style of the tales as they told them. Wilhelm Grimm edited the tales, inventing beginnings and endings: “Es war einmal …” and “… und sie lebten vergnügt bis an ihr Ende;” “Once upon a time …” and “… and they lived happily ever after”. Moreover, rather than gather tales from the peasantry, for the most part they seem to have gathered narratives from bourgeois ladies. The preface to the second volume of the tales named one source as a farmer’s wife, Dorothea Viehmann; she was actually a tailor’s wife who lived in a city. She was also of French Huguenot extraction, and knew the French fairy tales of Perrault and the précieuses. The distinction between traditional tales and shaped artistic work, between volkspoesie and kunstpoesie, was hopelessly blurred.

Oddly, they didn’t stick to this theory with their own collection of folktales, the Kinder- und Hausmärchen, the first volume of which was published in 1812, with the second following in 1815. They revised their books constantly over the years, in later printings toning down the earthier and more sexual elements (though occasionally increasing the violence) in a successful bid to make a collection aimed at children. They shaped the style of the tales as they told them. Wilhelm Grimm edited the tales, inventing beginnings and endings: “Es war einmal …” and “… und sie lebten vergnügt bis an ihr Ende;” “Once upon a time …” and “… and they lived happily ever after”. Moreover, rather than gather tales from the peasantry, for the most part they seem to have gathered narratives from bourgeois ladies. The preface to the second volume of the tales named one source as a farmer’s wife, Dorothea Viehmann; she was actually a tailor’s wife who lived in a city. She was also of French Huguenot extraction, and knew the French fairy tales of Perrault and the précieuses. The distinction between traditional tales and shaped artistic work, between volkspoesie and kunstpoesie, was hopelessly blurred.

Coincidentally or not, at about this time a flowering of Late Romantic fantastic tales took place. A number of writers began producing prose fiction, both novel length and shorter works, notable not only for the marvels in their plots but sometimes also for their structural daring. Adelbert von Chamisso’s 1814 Peter Schlemihls wundersame Gaschichte (The Wondrous History of Peter Schlemihl) told the story of a man without a shadow. Johann August Apel published collections of ghost stories he’d gathered, in annual collections called Gespensterbuch, from 1811 to 1815; one of these books, translated into French as Fantasmagoriana, was read at a certain memorable evening at the Villa Diodati in Geneva (more on that next week, I think). Wilhelm Hauff wrote several novels and three cycles of fairytales; the novels include 1826’s Liechtenstein, a historical tale with supernatural overtones, 1825’s satirical Memoiren des Satan (Memoirs of Satan, volume 2 published 1826), and 1828’s Das kalte Herz (The Cold Heart), a parable about nature and commerce. Joseph Eichendorff’s Das Marmorbild (The Marble Image, 1818) described a man caught between Venus and Christianity. Friedrich de la Motte Fouqué wrote a tale praised by Coleridge and (later) George MacDonald in his Undine, the tragic story of a knight and a water spirit (1811). Perhaps greatest of them all, from 1814 to his death in 1822 Ernst Theodore Amadeus Hoffmann wrote short stories — and two novels — that took fantastic material of all kinds, fairy tales and ghost stories and crime stories and historical fiction, and mixed them together in fascinating, powerful ways.

I personally consider Hoffmann to be one of the world’s greatest short story writers. A talented cartoonist whose caricatures once cost him a coveted government post, and a gifted musician whose opera based on de la Motte Fouqué’s Undine has shown real staying power, Hoffmann’s fiction is by turns urbane, wondrous, ironic, horrific, funny, and thoughtful. Above all, it’s grotesque; but it’s the grotesquerie that derives from the rapid and unpredictable switch between radically different registers of tone and emotion. It’s usually seen as part of the märchen tradition; to me, it’s clearly a part of the tradition of the fantasy short story — specifically, it is effectively the beginning of the tradition.

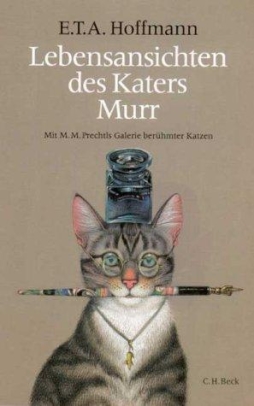

Hoffmann’s fiction exploits the structural freedom of Romantic prose to the utmost. He uses stories-in-stories, framing stories, flashbacks, and any number of other devices to help create a shifting world that is always specific but insists on being interpreted in multiple ways. His 1820 novel Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr nebst fragmentarischer Biographie des Kapellmeisters Johannes Kriesler in zufälligen Makulaturblättern (The Life and Opinions of Kater Murr, Including a Fragmentary Biography of the Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler on Miscellaneaous Pieces of Scrap Paper) takes the form of a self-satisfied autobiography written by Murr, Hoffmann’s cat, on the backs of paper containing bits and pieces of the biography of a conductor named Johannes Kreisler — a longstanding fictional alter ego of Hoffmann’s. Hoffmann is one of the greatest and most wonderfully strange writers I have ever come across, and his fiction is, to me, one of the great triumphs of Romanticism. It is utterly characteristic of the movement, and I think vital for the later development of fantasy, not only in terms of its direct influence on later writers like Poe, but in the way that Hoffmann creates or perfects techniques and approaches still to be found in modern fantasy — the structural dexterity, the balance of irony and symbol, the ability to build an atmosphere through elegant description and also call that atmosphere into question without breaking it. I would say, in fact, that Hoffmann’s work still seems to me to hold a storehouse of potential for future writers; it is profoundly suggestive, and could perhaps be studied indefinitely with profit.

Hoffmann’s fiction exploits the structural freedom of Romantic prose to the utmost. He uses stories-in-stories, framing stories, flashbacks, and any number of other devices to help create a shifting world that is always specific but insists on being interpreted in multiple ways. His 1820 novel Lebens-Ansichten des Katers Murr nebst fragmentarischer Biographie des Kapellmeisters Johannes Kriesler in zufälligen Makulaturblättern (The Life and Opinions of Kater Murr, Including a Fragmentary Biography of the Kapellmeister Johannes Kreisler on Miscellaneaous Pieces of Scrap Paper) takes the form of a self-satisfied autobiography written by Murr, Hoffmann’s cat, on the backs of paper containing bits and pieces of the biography of a conductor named Johannes Kreisler — a longstanding fictional alter ego of Hoffmann’s. Hoffmann is one of the greatest and most wonderfully strange writers I have ever come across, and his fiction is, to me, one of the great triumphs of Romanticism. It is utterly characteristic of the movement, and I think vital for the later development of fantasy, not only in terms of its direct influence on later writers like Poe, but in the way that Hoffmann creates or perfects techniques and approaches still to be found in modern fantasy — the structural dexterity, the balance of irony and symbol, the ability to build an atmosphere through elegant description and also call that atmosphere into question without breaking it. I would say, in fact, that Hoffmann’s work still seems to me to hold a storehouse of potential for future writers; it is profoundly suggestive, and could perhaps be studied indefinitely with profit.

If Hoffmann’s work is the defining triumph of Late Romanticism in German, there still remains another text to discuss before concluding this post. Goethe died in 1832 (in the early morning, famously calling out for “more light!”) having published Faust Part 2 earlier that year. Far longer than Part 1, it’s also much more ambitious, an epic in the form of a verse drama. It’s a phantasmagoria of symbol, allusion, and story. Faust’s traditional tryst with Helen of Troy becomes here a symbol for the fusion of German and Classical culture; the two have a son, Euphorion, who symobolically represents the English Romantic writer Lord Byron. But although the play’s dense with meaning, acquiring a dreamlike feel as Faust hurtles from one resonant scenario and situation to another, it also describes his character as it moves along its way to what ought to be a tragic end — and yet, miraculously, is not. Goethe’s Faust is one of the highest achievements of the fantastic in literature, the product of decades of work and study by one of the greatest of Europe’s writers. In French, one speaks of the French language as la langue de Molière; of English as la langue de Shakespeare; of Spanish as la langue de Cervantès — and of German as la langue de Goethe.

Although Goethe had decisively rejected the label ‘Romantic,’ it seems a resonant coincidence that German Romanticism faded in the years after his death. Although Romanticism was on the ascendant in France, it was, as we shall see, waning in England. But throughout the German Confederation the conservative settlement and control over the press that had settled in following the Conference of Vienna seemed opposed to the wild, radical, individualistic Romantic notions of genius. The satirical character of Beidermeier, the self-satisfied small-minded bourgeouis, seemed to embody the new age. As time went on, a new wave of liberal political writers emerged, later known as the Vormärz, or “pre-March” — pre-March of 1848, when revolution broke out. These writers were engaged and socially-aware, but did not have the Romantic concern for the transcendent. The Romantic age had passed.

In 1790, the word ‘romantik’ appeared in German, referring to a writer of novels, ‘romane.’ By 1810, it was used by the artistic opponents of the Romantic writers to mock their movement, identified with novels by the Schlegels. By 1833 it was used in a neutral sense in Heinrich Heine’s survey of contemporary literature, Die romantische Schule. From there, it moved to English, ‘Romanticist’ appearing about 1850. Similarly, the influence of German Romantics on the English writers of the era should not be overlooked. I think that the German writers were on the whole more programmatic in defining their movement, consciously articulating philosophy and critical principles; English Romanticism, important as it is, has a more ad hoc feel, a group of disparate writers and groups associated by a few trends. I don’t think it would be right to say that the Germans anticipated the English Romantic writers — who, by the nature of their times and sensibilities, were finding their own individual means of expressions. But I do think the Germans, in addition to the relevance of their work for their own concerns, worked out approaches and techniques that had a tremendous impact on English Romanticism — and on fantasy in English, at the time and in the years since.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Over the years I’ve seen all these names floating about in the soup, but lacked a coherent framework for the non-Anglophone romantics. This was a very useful post. Thank you.

My first contact with Hoffmann was via my girlhood’s mandatory piano lessons, age 7 – 14. At each level of progress, one of the series of practice books used stripped down for piano pieces from operas. Always included was something out of Offenbach’s Tales of Hoffmann. At the top of the pieces were brief biographies of the composer, period illustrations of the work at hand, and descriptions of the history and milieu out of which the work had emerged, thus this writer became a familiar name, and a collection of his tales one of the first books I bought for myself with my first paying job.

As you can imagine, I absorbed without noticing an enormous amount of historical, artistic and costume information from those loathed years of piano lessons and enforced daily practice, which has served me very well ever since.

Love, C.

Sarah: Glad it helped! I had much the same reaction as I put it together, to tell you the truth.

C: That’s the neat thing about an artistic tradition — it almost always connects up with other traditions in unexpected ways. So it can lead one into all sorts of different directions. That said, those sound like really well-put-together practice books!

Well, as you surely know so well, music is really where the idea – ideal of Romanticism began. The individual composer who is know, the individual performer (which depended enormously upon the development of tuning and the piano), and where the two intersected — and how some of them attempted throughout the 19th century to bring the ‘folk’ and and the authentic into the theatrical venue.

Love, C.

[…] starting with the poems of Ossian. I went on to talk about Romanticism and fantasy in France and in Germany before returning to England to discuss Gothic fiction. In those last two posts, I found myself […]