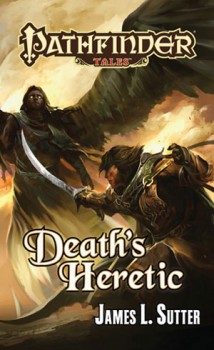

Black Gate Interviews James L. Sutter, Part One

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder, Death’s Heretic, and sheds a little light on one of fantasy’s gray areas. Over the next two weeks we’ll be covering a range of topics as James divulges on media-tie in fiction, early reading, assembling the killer lineup of the Before They Were Giants anthology, working in the game industry, and turning off the ‘editorial eye.’

I recently caught up with Paizo’s James Sutter for a conversation about his work heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line, as well as his own writing and influences. In part one of our conversation James tells us about his new novel for Pathfinder, Death’s Heretic, and sheds a little light on one of fantasy’s gray areas. Over the next two weeks we’ll be covering a range of topics as James divulges on media-tie in fiction, early reading, assembling the killer lineup of the Before They Were Giants anthology, working in the game industry, and turning off the ‘editorial eye.’

A Conversation with James L. Sutter

Death’s Heretic is your first published novel, so that seems like a pretty good place to begin the conversation. Tell us a bit about the book and about Salim, Death’s Heretic’s protagonist.

First off, Death’s Heretic is a Pathfinder Tales novel, which means that it’s set in the campaign setting for the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game. Fortunately for me, while it’s a shared-world novel, it’s a shared world that I’ve been helping to create over the last several years, and I had a lot of free reign with regard to the book’s setting.

The book is a fantastical mystery set in the desert nation of Thuvia, where folks with enough money can bid on an extremely rare potion which acts like a fountain of youth. A lot of people will do anything for a few more years of life and youth, so it’s not too surprising when one particular merchant wins the annual auction and winds up assassinated. The surprising part comes when the priests of Pharasma, the death goddess, go to resurrect him, only to find that his soul’s been stolen from the afterlife by an unknown kidnapper, who’s offering to ransom the soul back for the merchant’s dose of the elixir.

That’s where Salim comes in. A former priest-hunting atheist, Salim hates the death goddess with a passion, yet is bound against his will to act as a problem-solver and hired sword for the church. In this case, he’s in for even more aggravation than usual, as the investigation is being financed by the merchant’s headstrong daughter, who demands to accompany him. Together, the two of them end up traveling all over the various planes of the afterlife in a race to uncover the missing soul, interacting with demons, angels, fey lords, mechanical warriors, and more.

At the risk of spoilers, to me the book is actually three stories: the mystery of the stolen soul, the story of how a staunch atheist ends up working for a goddess, and the colliding worlds of the hard-bitten warrior and the wealthy aristocrat.

Any particular challenges associated with the writing of Death’s Heretic? Telling a story that touches on extra-dimensional travel in the Outer Planes seems potentially very tricky.

Any particular challenges associated with the writing of Death’s Heretic? Telling a story that touches on extra-dimensional travel in the Outer Planes seems potentially very tricky.

Actually, the parts involving the Outer Planes were some of my favorite to write. When I was initially conceptualizing the book, I had just finished reading Clive Barker’s brilliant Imajica, and I knew I wanted to do a journey story that involved a bunch of unique landscapes and vistas. (As you might imagine from someone who does world design for a living, I enjoy a good setting more than just about anything.) So once I had a basic plot, the first thing I did was sit down and figure out which planes (and extraplanar entities) I most wanted to work with, and the outline developed from there.

In terms of challenges, most of the things that usually make a gaming tie-in book so difficult–the continuity, the magic system, making sure everything fits within the rules–were mitigated by the fact that, under normal circumstances, I’m the guy who checks that stuff for Paizo’s novels. But even working here, there’s still always the terror that something in your novel will contradict something in development somewhere else, and you’ll have to revise huge swathes. Fortunately, the one significant thing that changed on me during the writing–updated statistics which changed how the eternal-youth elixir works in-game–was a fairly easy fix. Though I’m sure my coworkers will tell you that there was a bit of panic sweat when I found out about that one.

Honestly, I think the single most challenging part of the process was coming up with the initial idea. I spend so much time immersed in Pathfinder that it was hard to pick just one aspect of the setting and follow it. But I’m fascinated by the idea of atheism in a fantasy world where the gods can be empirically proven, and by both immortality and the Outer Planes, so once I realized I could play with those toys, everything fell into place.

I find atheism in a fantasy setting full of demonstrably real gods, demons, angles, and assorted other ‘supernatural’ beings fascinating as well. How did you approach it? It’s more a question of refusing to submit to authority than active disbelief in Salim’s case, correct?

Correct. Salim is from a nation in our world called Rahadoum, which long ago got so fed up with holy wars that it outlawed religion altogether. Salim grew up in that environment, and so he has a very interesting outlook on both gods and religion. As far as he and his countrymen are concerned, the gods are real–it’s hard to argue with that, when you can potentially go meet one in person if you’re powerful and foolish enough–but they view them much the way we think of ancient Greek and Roman gods: as essentially big, superpowerful people, with all the normal anthropomorphic desires and faults. As Salim points out to Neila (the merchant’s daughter) at one point, the gods are certainly powerful–but so are kings, and emperors, and anybody who has a sword when all you’ve got is a rock. Does that mean they deserve to be worshiped? To a Rahadoumi, every religion is essentially a Faustian bargain in which you’re promising your soul to someone–it doesn’t matter whether that master is benign or malevolent, it’s still indentured servitude. So their brand of atheism is less about actively denying the gods, and instead about asserting their independence (even though that independence puts them at a distinct disadvantage compared to pious nations).

And that’s only one potential take on things. In one of our office Pathfinder games, I spent several years roleplaying a character named Kirin who was a more extreme type of atheist–he refused to believe in gods at all, and instead accused those priests who worked miracles of just being sorcerers who were too cowardly to admit that they were the ones working the magic, and who were trying to avoid responsibility by blaming a mystical higher power if things went wrong. A much harder position to defend, but a fun one to roleplay!

In fact, totally outside of Pathfinder, I’ve got another fantasy story that’s currently slated to show up in Black Gate which takes a look at the interplay of morality and abortion in a fantasy world where the deities can literally state their opinions. So religion has always been something I’ve been interested in where fantasy’s concerned–and especially how it intersects with questions of morality. Fantasy’s a lot of fun, but I think the old good guys vs. bad guys trope can get stale (and terribly unrealistic) if you don’t inject some gray areas in there. I frequently drive my coworkers nuts trying to raise questions and muddy the waters around what constitutes good and evil in our world. (Ask them about my dragon eugenics experiment sometime.)

Be sure to check out part two of Black Gate’s interview next week where we talk more in depth about Pathfinder Tales, editing, and how games relate to fiction.

___________

James Lafond Sutter is the author of the novel Death’s Heretic, as well as numerous science fiction and fantasy stories for such venues as Starship Sofa, Black Gate (forthcoming), Apex Magazine, and the #1 Amazon bestseller Machine of Death. His anthology Before They Were Giants pairs the first published short stories of speculative fiction greats from Ben Bova and Larry Niven to China Miéville and William Gibson with anecdotes and instructional critiques by the authors themselves. In addition to writing fiction, James has also authored dozens of roleplaying game products, and is the Fiction Editor for Paizo Publishing, as well as a co-creator of the Pathfinder Roleplaying Game campaign setting. For more information, please visit www.jameslsutter.com.

BILL WARD is a genre writer, editor, and blogger wanted across the Outer Colonies for crimes against the written word. His fiction has appeared in numerous magazines and anthologies, as well as gaming supplements and websites. He is an Editor at Black Gate, and 423rd in line for the throne of Lost Lemuria. Read more at BILL’s blog, DEEP DOWN GENRE HOUND.

That opening description of Death’s Heretic sounds pretty enticing James. Congrats on pulling it off in spite of your intimacy with the material 🙂

Who’s the artist on this?

[…] week we were just getting started in our conversation with writer James L. Sutter; this week we talk more about James’ role at Paizo, the balance between editing and writing, […]

[…] and eBooks for a while now, exploring the world of Pathfinder RPG in long and short fiction. Bill Ward at Black Gate recently had a chance to interview James Sutter, who’s heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line and just published his first novel […]

[…] of many big name writers, and a look at what James is working on now. Be sure to check out parts one and two of this interview, as well as our review of James’ new novel Death’s […]

[…] with James L. Sutter (Part 1, Part 2, Part […]

[…] and eBooks for a while now, exploring the world of Pathfinder RPG in long and short fiction. Bill Ward at Black Gate recently had a chance to interview James Sutter, who’s heading up Pathfinder’s new fiction line and just published his first novel […]