Edgar Rice Burroughs’s Pellucidar Saga: Savage Pellucidar

Have we already arrived at the end of Pellucidar? It feels like I started examining this Edgar Rice Burroughs series only a few months ago — but it’s been almost a year since I drilled down to visit At the Earth’s Core. A year may have passed for me, but thirty has passed for Burroughs, and counting the time until the last unpublished novella was collected in Savage Pellucidar, the gap widens to fifty years. If you read At the Earth’s Core in the pulps as an enthusiastic thirteen-year-old, you’d be close to retirement age by the time you could buy the last book and have a complete Pellucidar set.

Have we already arrived at the end of Pellucidar? It feels like I started examining this Edgar Rice Burroughs series only a few months ago — but it’s been almost a year since I drilled down to visit At the Earth’s Core. A year may have passed for me, but thirty has passed for Burroughs, and counting the time until the last unpublished novella was collected in Savage Pellucidar, the gap widens to fifty years. If you read At the Earth’s Core in the pulps as an enthusiastic thirteen-year-old, you’d be close to retirement age by the time you could buy the last book and have a complete Pellucidar set.

Wait, what am I talking about? This is Pellucidar. Time is meaningless here! I started writing this article series yesterday — or maybe a century ago, and the books were all published either over a span of one year or five hundred years. It’s all the same under the perpetual noonday sun.

Our Saga: Beneath our feet lies a realm beyond the most vivid daydreams of the fantastic … Pellucidar. A subterranean world formed along the concave curve inside the earth’s crust, surrounding an eternally stationary sun that eliminates the concept of time. A land of savage humanoids, fierce beasts, and reptilian overlords, Pellucidar is the weird stage for adventurers from the topside layer — including a certain Lord Greystoke. The series consists of six novels, one which crosses over with the Tarzan series, plus a volume of linked novellas, published between 1914 and 1963.

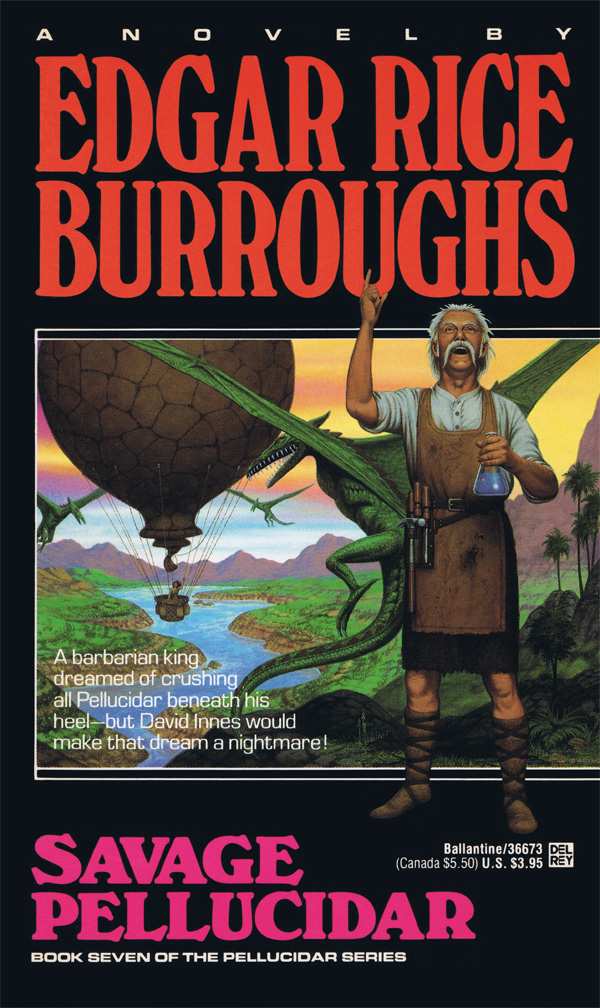

Today’s Installment: Savage Pellucidar (1963)

Previous Installments: At the Earth’s Core (1914), Pellucidar (1915), Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929–30), Back to the Stone Age (1937), Land of Terror (1944)

The Backstory

I’ve told this tale before with Escape on Venus and Llana of Gathol, the sister works of Savage Pellucidar, but once more won’t hurt. At the start of the 1940s, Edgar Rice Burroughs experimented writing novels in three of his settings — Mars, Venus, and Pellucidar — as sets of four linked novellas. Each novella was capable of standing on its own but could later fit together with the other three for book publication. The idea may have been the suggestion of Cyril Ralph Rothmund, business manager for ERB Inc., who first wrote a letter to the editor of Ziff-Davis Magazines with the format proposal. It was an experiment of necessity, since the pulps were turning away from serializations as more of the weekly magazines dropped to monthly publication. Burroughs approached the three books as a round-robin, changing from one setting to the next to finish all the novellas.

But where the individual parts of Escape on Venus and Llana of Gathol all appeared one month after the other in the pulps during 1941–42, only the first three parts of what Burroughs planned to called The Girl of Pellucidar were published. “The Return to Pellucidar,” “Men of the Bronze Age,” and “Tiger Girl” debuted in Amazing Stories in the February, March, and April 1942 issues. But the fourth installment didn’t follow in May — or any other month for the rest of ERB’s lifetime.

What happened? Ziff-Davis Magazines decided it was all booked up with ERB material before the last Pellucidar novella was written. Burroughs intended to complete the sequence so he could publish the book edition, but the urgency had vanished. Once the U.S. entered World War II, Burrough’s work as a war correspondent caused further delay. He didn’t finish the last novella, “Savage Pellucidar,” until October 1944. He never submitted it for publication.

The missing novella was discovered along with other unpublished Burroughs works during an ERB Inc. office inventory in 1963 after Rothmond’s retirement. “Savage Pellucidar” was published simultaneously in the still-going Amazing Stories for November 1963 and then in a Canaveral Press book, now carrying the name of the last novella, Savage Pellucidar. The four stories were united as intended, and the Pellucidar saga came to a close thirteen years after its author’s death.

The missing novella was discovered along with other unpublished Burroughs works during an ERB Inc. office inventory in 1963 after Rothmond’s retirement. “Savage Pellucidar” was published simultaneously in the still-going Amazing Stories for November 1963 and then in a Canaveral Press book, now carrying the name of the last novella, Savage Pellucidar. The four stories were united as intended, and the Pellucidar saga came to a close thirteen years after its author’s death.

The Story

There’s no prologue or framing device, but the first sentences are a great summation of Pellucidar: “David Innes came back to Sari. He may have been gone a week, he may have been gone for four years. It was still noon.”

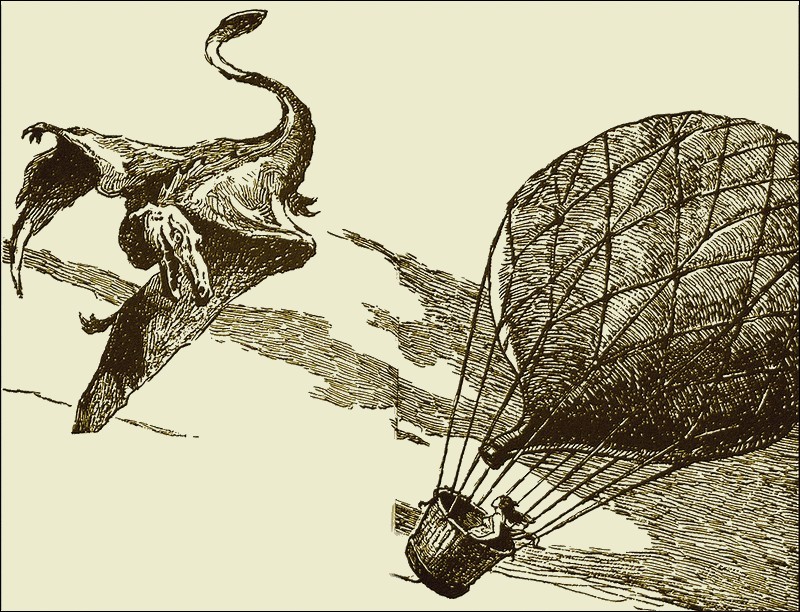

Innes makes an expedition to the marches of his Empire of Pellucidar to settle a dispute with the breakaway kingdom of Suvi. While he’s gone, Abner Perry tests out a new hot air balloon and loses Dian, Innes’s mate, in it when the balloon snaps free and floats off. Dian eventually comes to ground between two warring cities with Bronze Age technology, Tanga-Tanga and Lolo-Lolo. The Lolo-Loloans take Dian into their city, believing she is a goddess called the Noada.

Meanwhile, David Innes falls into a trap during the expedition to Suvi, leaving Hodon the Fleet One, a Sarian warrior, and O-aa, daughter of a local king, to attempt to rescue him. While they’re temporarily captives of a tribe of sabertooth men, Hodon and O-aa discover a prisoner from the surface world: a Cape Cod fisherman whose whaling vessel went down Pellucidar’s Arctic opening in 1844. The fisherman, who adopts the Pellucidarian name of Ah-gilak (“old man”), is also crazy and a cannibal — but our heroes let him tag along on their adventures because he can build boats, is an excellent sailor, and creates running gags.

A misunderstanding between Hodon and O-aa causes her to flee from him. She’s swept into the Nameless Strait between Tanga-Tanga and Lolo-Lolo, where the Tanga-Tangans grab her and proclaim her to be their Noada. O-aa and Dian overturn the politics of their two cities and ignite violent rebellions. Dian escapes Lolo-Lolo before a riot driven by the head priest kills her. David, looking for Dian, arrives in Tanga-Tanga where he helps O-aa stop an uprising fomented by the city’s jealous king.

Hodon searches for O-aa, who was separated from David after they left Tanga-Tanga. But O-aa manages fine on her own in the meantime, having struck up her own hunt-and-kill partnership with a wolfhound (jalok) named Rahna. Hodon eventually finds O-aa and their love no longer has any obstacles. Soon all the heroes are reunited and happily back home in Sari. Only Ah-gilak is discontent, because he never got to eat anybody.

The Positives

The Positives

Of the three novellas-into-novels Burroughs wrote simultaneously, Savage Pellucidar is the finest by many mammoth strides. It’s among the best of ERB’s 1940s output and a titanic improvement over the previous two meandering Pellucidar installments. I’m unsure why Pellucidar would pull ahead of Mars at this point (nobody should be shocked that it got ahead of Venus), but Burroughs invested more storytelling craft and character creation into this novella sequence than he did for Llana of Gathol. And where that book sported a woman’s name in the title but never gave her much to do aside from the “get kidnapped/get rescued” routine, Savage Pellucidar is a book with real heroines: Dian the Beautiful and newcomer O-aa of Kali.

Unlike Llana of Gathol and Escape on Venus, Savage Pellucidar feels like a cohesive novel rather than repetitive episodes. It’s difficult to imagine readers in 1942 enjoying the first three installments as independent works, since each overlaps with the next without hard conclusions. However, I’m looking at this as a complete book, and in this context it succeeds. There’s no circular repetition of a formula; Burroughs changes the complications and adventure style as he would for a standard serialized novel. The story can become tangled with multiple plot threads running concurrently and constant shifts in location, but nothing feels inconsequential or present merely to fill space. I’d much rather have a tricky mesh of exciting events than a string of bland encounters, as in Land of Terror.

Although Hodon pops up in the hero slot in the opening chapters, the novel’s actual protagonist is O-aa. She not only has more time devoted to her, she’s the runaway success of the book. O-aa makes an inauspicious first appearance when Hodon meets her: she’s a chatterbox who continually brags about her many siblings (actual siblings = 0) and soon grates on Hodon’s nerves. This is when a warning siren will go off in the reader’s brain: Oh, no, she’s not going to hang around for the rest of the book with this shtick, is she?

But O-aa quickly defies expectations and shows herself as intelligent, capable, and brave. The first man who kidnaps her lasts only a few pages before O-aa skewers him with his own spear and hurls the corpse overboard to keep a pursuing water monster off her trail. In Tanga-Tanga she figures out the city’s economy so she can turn the tables on the lazy, grifting priesthood. Even her brags about fictional relatives change from jokes into effective tools to bluff her opponents. When a sailor aboard Ah-gilak’s ship makes aggressive advances on her, she threatens to stab him — and readers have no doubt she’ll do it. O-aa doesn’t take crap from anybody and her follow-through is deadly.

When O-aa teams up with the wolfhound Rahna in the last novella, Savage Pellucidar fulfills the promise of its working title, The Girl of Pellucidar. O-aa is the unquestioned star of the book and a full-fledged action heroine. Getting an animal sidekick just seals the deal. O-aa deserved a novel of her own.

As for the other standout female role: wow, the change Burroughs made with Dian! Although she’s the love interest of the principal hero of the Pellucidar series, Dian hasn’t done much until now. She has a few standout bits in At the Earth’s Core, but nothing compares to her transformation here into a full-fledged wildcat in parallel with O-aa. Dian gets some startlingly hardcore moments, such as stabbing one of her captors to death and fending off a plesiosaur-like creature attacking her canoe. Her crowning moment of awesome is when an unwanted suitor tries to force her back to his village, and Dian sics her sabertooth companions on him, who rip him to shreds. Good stuff — savage Pellucidar indeed!

Ah-gilak, the crazy cannibal from Cape Cod, is both something that does and doesn’t work. I’ll get to the latter below, but without question Ah-gilak is a character readers won’t forget. Introducing a new above-worlder to Pellucidar was a smart strategy to freshen the cast. But Burroughs went above the call of duty by making Ah-gilak 1) a salty Yankee, 2) insane, and 3) an enthusiastic cannibal who doesn’t understand why everybody else isn’t onboard with eating each other when they’re in a tight spot. (When caught trying to murder one of his companions so he can start eating early, he defends himself by saying he was going to share.) Ah-gilak is a playfully strange creation who’s a delight to have around even during the stretches when he doesn’t serve much purpose. No other character is like him in the Pellucidar novels, and it’s clear Burroughs had fun writing him.

Ah-gilak, the crazy cannibal from Cape Cod, is both something that does and doesn’t work. I’ll get to the latter below, but without question Ah-gilak is a character readers won’t forget. Introducing a new above-worlder to Pellucidar was a smart strategy to freshen the cast. But Burroughs went above the call of duty by making Ah-gilak 1) a salty Yankee, 2) insane, and 3) an enthusiastic cannibal who doesn’t understand why everybody else isn’t onboard with eating each other when they’re in a tight spot. (When caught trying to murder one of his companions so he can start eating early, he defends himself by saying he was going to share.) Ah-gilak is a playfully strange creation who’s a delight to have around even during the stretches when he doesn’t serve much purpose. No other character is like him in the Pellucidar novels, and it’s clear Burroughs had fun writing him.

The crazy old fisherman adds a new wrinkle to the protean nature of time in Pellucidar. Perry and David seem to have aged only a few years since they arrived in 1913, but now we have a 153-year-old man confirming that the unusual flow of time in Pellucidar isn’t only an illusion created by the eternal high noon sun. Time is objectively irrational at the earth’s core. If Burroughs wrote more Pellucidar novels, he might have brought in upperworld visitors from the far past and the far future and I’d believe it.

After two books without much in the way of humorous authorial commentary, Burroughs returns to the vein of oddball observation comedy/satire. He branches off a bit with these diversions, but they keep the writing lively: “Dragging O-aa was like dragging a cat with hydrophobia; O-aa didn’t drag worth a cent.” “O-aa has never been on a rollercoaster; but she was getting the same sort of thrills out of this experience; it lasted much longer, and she didn’t have to buy any tickets.” A frightened O-aa “peopled the world with terrifying menaces, which was wholly superfluous, as Nature had already attended to that.” These are just the comic bits around O-aa. Abner Perry deserves his own section.

Perry’s role isn’t huge, but it’s good to have the loony inventor and original co-star of At the Earth’s Core around. It appears Perry completely lost his mind during his decades in Pellucidar. As usual, his inventions either don’t work or are missing essential components: he built rifles without triggers and forgot to put a ripcord in the hot-air balloon. Conventional absent-minded academic stuff. When it comes to weapons of mass destruction, however, Perry’s gone over the cliff. In the opening chapter, he’s giddy over the thought of the mass killings possible with aerial bombs: “Think of the vast stride it will be in civilizing these people! Why, we should be able to wipe out a village with a few bombs.” He’s ready to move on to using poison gas to slay even greater numbers. ERB attempts to soften Perry by explaining that his “plans for slaughter were purely academic” and he also brought a peaceful influence to Pellucidar. I don’t buy it; Perry is cracked and I’m fine with that.

Perry’s calculations of slaughter show a shift in Burroughs’s approach to war and violence. Previously he portrayed violence in his stories through a romantic, swashbuckling lens. But in the 1940s his style changed: warfare became an ugly, gory affair with little chivalry. This peaked in the astonishing Tarzan and the “Foreign Legion” and its view of fighting in WWII not as red-white-and-blue patriotism but crimson vengeance. This angry pessimism is present in the last Pellucidar novel, which contains moments of extreme violence motivated only by rage. The detailed description of Hodon killing Blug, his romantic competition for O-aa, has him using a huge rock to repeatedly smash the man’s skull until Blug’s head is a jellified pulp. Even for Burroughs, this is overkill.

There are nastier, real-world shocks coming. When the people of Lolo-lolo turn against Dian, the book delivers a paragraph of biting sarcasm with a direct reference to Nazi atrocities:

Remember, they were just simple people of the Bronze Age. They had not yet reached that stage of civilization where they might send children on holy crusades to die by thousands; they were not far enough advanced to torture unbelievers with rack and red-hot irons, or burn heretics at the stake; so they believed this folderol that more civilized people would have spurned with laughter while killing all Jews.

This is one of the darkest, bleakest passages to appear in any of Burroughs. It’s not the sly cynicism of his early writing; this is pure misanthropy, and that it arises from World War II is made clear in the chilling final words.

This is one of the darkest, bleakest passages to appear in any of Burroughs. It’s not the sly cynicism of his early writing; this is pure misanthropy, and that it arises from World War II is made clear in the chilling final words.

Readers may find such violence and dark patches in a Pellucidar novel a negative, but they show Burroughs changing as a writer, something he needed to do after the stagnation of the late 1930s. The creative upswing during his final productive years is partially because of a deepening interest in the human capacity for evil and the need to find escape. One of the effects of the WWII on Burroughs was to create a longing for the violent fantasy worlds of his own creation to replace the violent real world he lived in.

The Negatives

Burroughs put a bit too much incidence in Savage Pellucidar so that it occasionally becomes tricky to sort out the strands. ERB often wrote concurrent action plotlines and flipped between them; the majority of the Tarzan novels use this technique. It’s undisciplined here, possibly because Burroughs wrote the novellas at separate times and lost momentum with individual plot strands. It can be tough keeping track of which of the many sailing ships is searching for what lost character and which unwanted suitor is currently pursuing Dian or O-aa (and likely to get his liver perforated). This confusion isn’t ruinous, since the events around the main characters remain clear, such as the political machinations in the dueling Bronze Age cities of Tanga-Tanga and Lolo-Lola.

Still, the book would’ve benefitted from a tighter focus on the most important characters for longer periods, with the other action left off the page to be explained later during one of the reunions. This was how the better Tarzan books played out. In fact, Tarzan at the Earth’s Core is a fine example of the storytelling precision Savage Pellucidar needs more of.

The character who deserves the most trimming is Hodon. A consequence of having a heroine as potent as O-aa is that her requisite love interest — and this is an ERB novel, there has to be a love interest — becomes bland. Hodon isn’t worth O-aa’s time, and I wish she ended up with no one at the end. She has Rahna, she doesn’t need anything else! Of the various plot threads the book flips around to, whatever Hodon is up to at the moment is the easiest one to forget about. Except when he smashes in Blug’s head. That one stays with you.

For all its fantastic Dian and O-aa action, Savage Pellucidar doesn’t have a rattling climax, which is where the faults of the novella style catch up with it. The finale has O-aa and Rahna in a hopeless battle with a tarag until Hodon and local tribesmen arrive to save the day. The main lovers are reunited, and within two pages everyone else is reunited. The End. ERB has certainly ended books on bigger anticlimaxes — like the previous Pellucidar novel — but the final book of the series should’ve closed with a huge battle. (Wouldn’t a return of the Mahars have been killer?) Instead, it’s O-aa and Rahna in an inconclusive tussle with a sabertooth cat. Ah well, Burroughs didn’t know it was his last Pellucidar book.

For all its fantastic Dian and O-aa action, Savage Pellucidar doesn’t have a rattling climax, which is where the faults of the novella style catch up with it. The finale has O-aa and Rahna in a hopeless battle with a tarag until Hodon and local tribesmen arrive to save the day. The main lovers are reunited, and within two pages everyone else is reunited. The End. ERB has certainly ended books on bigger anticlimaxes — like the previous Pellucidar novel — but the final book of the series should’ve closed with a huge battle. (Wouldn’t a return of the Mahars have been killer?) Instead, it’s O-aa and Rahna in an inconclusive tussle with a sabertooth cat. Ah well, Burroughs didn’t know it was his last Pellucidar book.

Ah-gilak is a great character concept, but ERB seems at a loss as to what to do with him for long periods. This turns awkward in the last novella, where the old fisherman from Cape Cod goes full villain, committing treachery against the crew of his ship and plotting against both O-aa and Dian. The consequences of his actions at the end are … nothing! Ah-gilak returns Dian and the Mezops back to Sari, and his only punishment is that he’s unhappy. For such a weird character, Ah-gilak shouldn’t have gone out in a tiny puff of smoke in the last paragraph. He should’ve eaten himself; he suggests it enough times.

It’d be remiss of me to leave out mention of a running joke about how Ah-gilak is “not named Dolly Dorcas.” Here’s the setup: O-aa heard the old man talking about his whaling ship, the Dolly Dorcas, and she assumed this is his name. Ah-gilak, who doesn’t recall his birth name, shouts repeatedly that his name isn’t Dolly Dorcas. Other characters comment on this, and the text then starts to refer to him as “the man who was not named Dolly Dorcas,” and … Look, the amount of time it took to explain all this should’ve been the limit of the joke. Yet it keeps trundling on all the way to the end, and it does not age well.

As effective as some of the comic authorial commentaries are, there’s no prologue or framing device to explain where they’re coming from. I’m unsure who is supposed to be narrating this story. A safe assumption is that it’s the pseudo-ERB who serves as the connective tissue between Burroughs’s books. But without the customary frame story — a place where Burroughs could indulge in free-wheeling fun with personal anecdotes — the commentary doesn’t feel natural with the third-person POV style, such as when it veers into a discussion of collar buttons and the dollar bill (see below). This isn’t a problem with other early twentieth-century authors, but with Burroughs we have decades of precedent.

The Bronze Age religion of the city of Lolo-Lolo mystifies Dian since religion and superstition are said to be unknown among the Stone Age Pellucidarians. But we know that isn’t true, since earlier books discussed the Pellucidarian’s belief in an afterlife where fire demons drag the buried dead down into a fiery sea called the Molop Az. Superstition seeps through much of the inner world’s culture, even if it doesn’t manifest as organized religion or recognition of specific deities. This makes me wonder why Abner Perry, a highly religious man when he’s not swearing at malfunctioning machinery, didn’t introduce concepts of religion to the Pellucidarians over the decades.

Craziest Bit of Burroughsian Writing: “Sometimes we are annoyed by the studied perversities of inanimate objects, like collar buttons or quail on toast; but we must remember that, after all, some of them are the best friends of man. Take the dollar bill, for instance — but why go on? You can think of as many as I can.”

Most Inventive Idea: Ah-gilak, the Crazy Cannibal from Cape Cod.

Best Creature: There are plenty of monsters on display, but nothing exceptionally new appears. However, watching Dian defeat a water saurian from a canoe is a huge thrill.

Carson Napier Memorial Foolishness Award: David Innes marches into the obvious trap Fash of Suvi lays for him. Fash ribs him about being so stupid.

Pellucidarian Understatement: After Hodon has crushed Blug’s head with a stone until it “was a jelly,” O-aa’s father Oose remarks, “Blug is not much good any more.”

How about a sequel? Unless ERB was planning a novel starring O-aa or finally making a trip to the pendant world, this is a good place to stop.

Next: A Pellucidar series wrap-up.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

It’s nice to see a Burroughs series actually end on a relatively high note.

I read the series as a ten almost all at once when the original ACE paperbacks were easily found and a paper route funded a huge package from the company where I spent a summer and winter devouring Burroughs. Back then I had no appreciation for the years between books and Pellucidar came across as one long continuous narrative from beginning to end. Have enjoyed your insights and laughed at the Dolly Dorcas joke being run in to the ground as I quickly tired of Ahgilak taking up much needed action space.

If you haven’t done it yet would love your take on The War Chief and Apache Devil which I believe is one of Burroughs best series and generally overlooked. A guilty pleasure read is The Mad King which made up for Rupert of Hentzau’s shock ending. Also much more exciting then any of the Graustrak novels I ever read.

@Allard, I definitely plan to do both The War Chief and Apache Devil next year at some time, because they are among ERB’s finest and also most personal (he thought highly of them). I do have a few other ERB bits planned before then, some weird one-shot material.