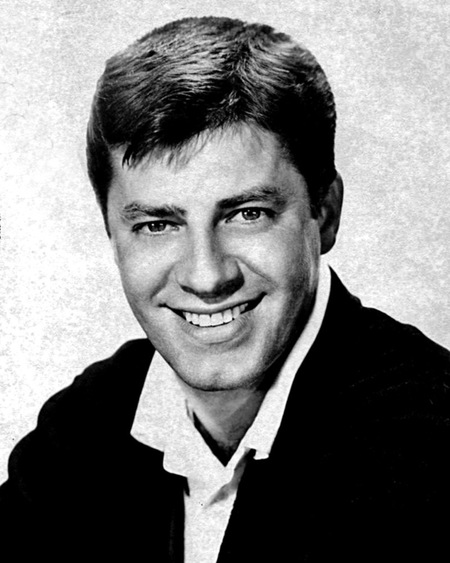

Jerry Lewis (Julius Kelp, Buddy Love), March 16, 1926 – August 20, 2017

The book has finally closed on the eight decade long career of Jerry Lewis, the American actor, comedian, and filmmaker, who died on Sunday, August 20th, at the age of ninety one. Jerry Lewis is one of those colossal, divisive figures like Lenin, Mao, or Meryl Streep; few people are noncommittal about him. Ever since he shrieked and jerked his way into the public consciousness with his partner Dean Martin, first in nightclubs and on radio, then in a series of highly successful movies, and finally, after an acrimonious split with Martin, on his own as an actor and director, the standard responses have been either overboard adoration or utter loathing, a split that even effects entire nationalities — the French have a much snickered-at (at least among Americans) reputation for their extreme and almost universal love of Lewis, while Swedes and all other Scandinavians can’t stand him. (I made that last part up, but it’s probably true.)

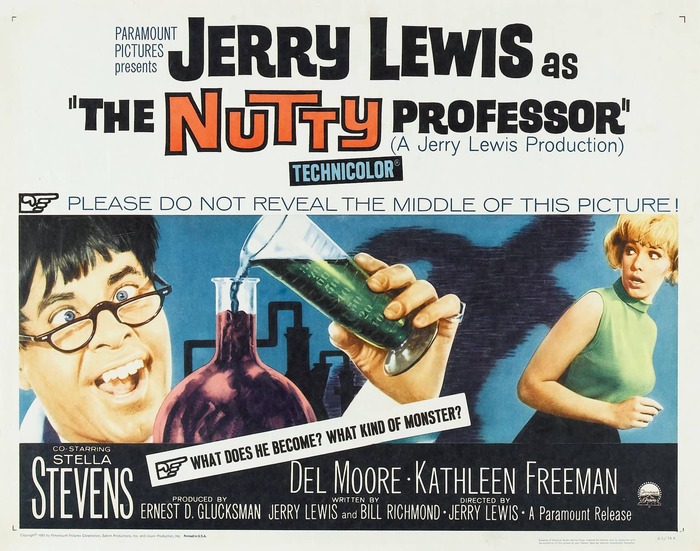

This might be of only passing interest to Black Gate readers, except for one thing. In 1963, Lewis co-wrote (with Bill Richmond), directed, and starred in what is arguably the best version of that much-filmed classic of dark fantasy, Robert Louis Stevenson’s The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Lewis altered the title even more than most adapters do, calling his movie The Nutty Professor, and that’s not all he altered.

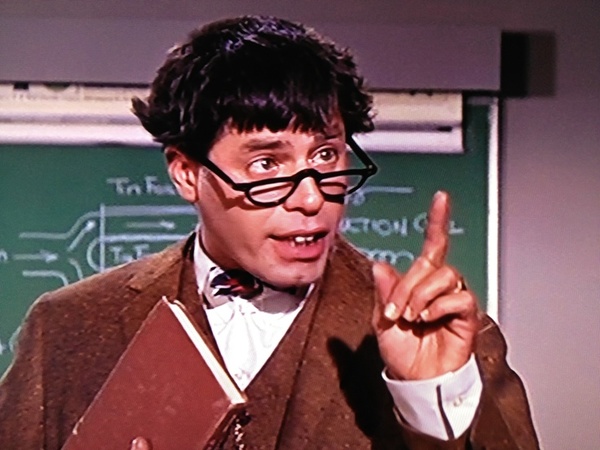

In the film, Lewis plays buck-toothed, bespectacled, timid, socially maladroit chemistry professor Julius Kelp. Kelp’s clumsiness extends well beyond the merely social; in addition to being inept with women, he has a bad habit of conducting unauthorized experiments that blow up his classrooms along with any students unfortunate enough to be in them. In fact, the film opens with a comically enormous explosion that happens because “I used… too much…”, and when the outraged head of the university, Dr. Warfield (Del Moore), reminds Kelp of another such mishap that occurred two years earlier (“the worst explosion in the history of this or any other university”), the following exchange takes place:

“Now that you mention that, Dr. Warfield, I saw young Phipps the other day — you recall Arnold Phipps was in my class that day?”

“Oh yes- – really? What did he have to say?”

“Well, he said he’s feeling much better and that the bandages should be off in about two weeks.”

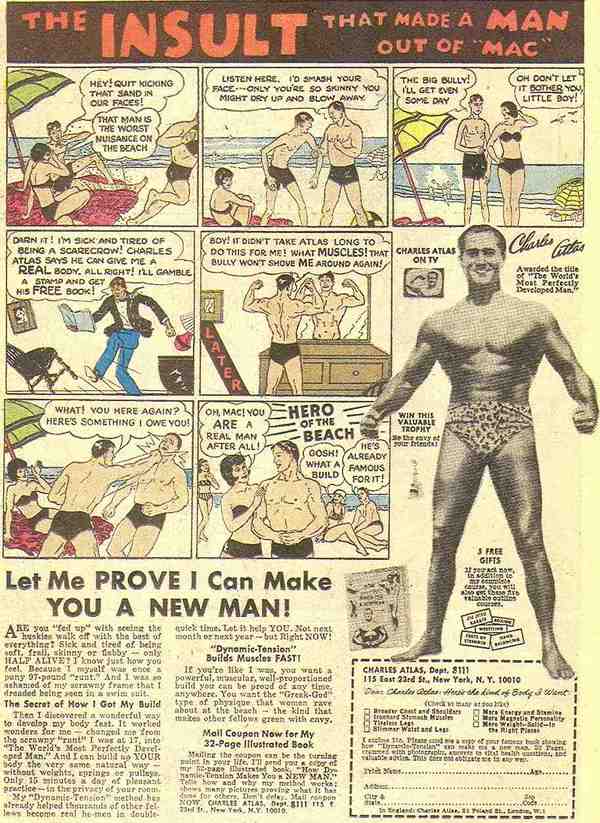

After a football player humiliates him in front of his other students, including the beautiful Stella Purdy (Stella Stevens), Kelp determines to alter his life by improving his physique, in the manner of the old “Insult that Made a Man Out of Mac” comic book ads.

A stint at the gym doesn’t work out too well though, as Kelp proves too awkward to use any of the equipment without precipitating disaster. Some of the sight gags in this part of the film are startling, as when the only result of Kelp’s attempt at lifting weights is to stretch his arms down to his ankles.

His workout regimen having flopped, Kelp turns to what he knows best: chemistry. He eventually concocts a formula that he believes will transform him into someone better than the shy weakling that he is and, hopes high, he quaffs the concoction and collapses to the floor. What follows is the film’s most famous sequence: the transformed professor’s stroll through town to the Purple Pit, a nightclub where all the students — including Stella Purdy — hang out.

The sequence is shot entirely from Lewis’ point of view. We have no idea what he now looks like (a brief shot or two in the lab leads us to believe that he may be devolving into some kind of Neanderthal); our only clue to his final appearance lies in the shocked expressions on the faces of everyone who sees him. The effect is accentuated by Lewis’ use of sound — the eerie, utter silence is broken only by the flustered stutter of the glassy-eyed clothing salesman who tells Lewis that he looks “uh…just stunning,” and Lewis’ loudly echoing footsteps as he walks up to the Purple Pit through a crowd of people who are frozen motionless with astonishment.

When he walks through the door of the nightclub, at first we still only “see” him through the reactions of other characters. Lewis’ POV camera moves slowly into the Pit, where a crowd is dancing to a swinging jazz combo. Then, as people slowly become aware of his presence, the music stops. The dancing stops. A cigarette girl’s stroll through the club comes to a screeching halt as she puts her hand to her mouth and lets all of her merchandise fall to the floor. A stunned waitress drops her tray into her oblivious customers’ laps. A couple stops in mid-kiss, the woman swiveling her head to see the Pit’s newest occupant so fast as to give herself whiplash. Her mouth hanging open, Stella Purdy herself stares as if she simply can’t believe her eyes.

Only then do we see the Mr. Hyde to Julius Kelp’s gentle Dr. Jekyll: the camera zooms in to show us, standing in the middle of the Purple Pit, the sneering, cigarette smoking, Brylcreemed, electric-blue suit wearing Buddy Love, the Lounge Lizard from Hell. This scene owes a little to the 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde directed by Rouben Mamoulian, which has many point of view shots, but Lewis’ use of them is more daring than anything Mamoulian attempted. In The Nutty Professor’s transformation scene, POV both builds suspense and heightens surprise as Lewis conceals and then reveals Kelp’s startling new identity. The effect is masterful, and makes the sequence a remarkable tour de force.

The obnoxious Buddy Love instantly displays his “charms”: he’s brash, bullying, rude, conceited, inconsiderate, self-involved, nauseatingly glib, vain… and those are his good points. (After Buddy insults a bartender, a patron gets in his face and says, “Why don’t you pick on someone your own disposition?” Love sarcastically replies, “Oh please, Mr. Barroom Brawler, don’t hurt me or anything like that,” and then pummels the fellow into unconsciousness, after which he pulls a mirror out of his jacket and checks his hair.)

After he commandeers the piano and wows the “kiddies” with a rendition of “That Old Black Magic” (Lewis’ singing isn’t exactly good, but it’s good enough to make you know how good it’s supposed to be in this skewed universe, if you get what I mean), the courtship of Stella Purdy commences, Buddy Love style. Love soaks up the applause, taking it as only his due, telling Stella, “Honey, I always say, if you’re good and you know it, why waste time beating around the bush — true?” Stella pushes back: “And I always say, that to love yourself is the beginning of a lifelong romance — and after watching you, I know that you and you will be very happy together.” She turns to walk away, but Buddy grabs her arm. “Just a minute, Sweetheart. I don’t recall dismissing you.” Stella is understandably enraged by this. “You rude, discourteous egomaniac!” she snaps.

But the armor of Buddy Love’s self-regard cannot be penetrated by any ordinary weapon known to man or — especially — woman. “You’re crazy about me, right? And I can understand it; only this morning, looking in the mirror, before shaving, I enjoyed seeing what I saw so much I couldn’t tear myself away.” Buddy kisses his hand lovingly, and, holding it out to Stella, says, “Have some, Baby?”

Stella cannot help being both repulsed and fascinated by this undeniably unique individual, and initially fascination wins out. They drive to a secluded spot above the city (in Stella’s car — Kelp drives a pastel green jeep, which isn’t exactly suited to be a Lovemobile) and, once parked, Buddy whips out a handkerchief, holds it out, and brusquely says, “Here you are, Baby — take this, wipe the lipstick off, slide over here next to me, and let’s get started.” At this, repulsion gains the upper hand and Stella demands to be taken home. Love persists, and when the shell-shocked woman says, “You must be deranged!” Buddy saves the day with that great speech which always does wonders on the screen but has never yet been known to work in any non-movie universe:

“Yeah, if you don’t believe in idle chatter, and a lot of small talk, yeah, I’m deranged. Or would you prefer that I conduct myself like the little boys you’re accustomed to dating? Now you know darn well that nothing delights us more than being enjoyed, appreciated, or just plain liked by someone, right? Now you’re not going to tell me that you’re here with me now because I don’t appeal to you. And I’m sure that you can see I dig you pretty good too. Right? Well, isn’t it easier to say so? Or would you much prefer that I used a lot of that phony dialogue that I’m sure you’ve heard at least a half a dozen times before? So you see, Stell, when I tell you that you’re a vibrant, beautiful, exciting woman, you can believe me. You can bet it’s the truth. Cause I’d have to be a complete idiot not to want to hold you, and kiss you, and make our time together a warm, wonderful moment that could grow and develop, into many moments, many hours, and into something really important.”

All during this spiel Stella progressively melts like butter in a hot pan. Buddy Love is triumphant; he has Miss Purdy just where he wants her, and then… his next oil-slick utterance comes out in the cracked, wavering voice of Julius Kelp. Uh-oh.

Without another word, Love flees into the night, leaving his flummoxed date to drive home alone, wondering what the hell just happened. This pattern will be followed for the rest of the movie, with the line between the two personalities blurring more and more, with Julius Kelp impinging back on Buddy Love at the most inopportune moments, and with Buddy Love gradually oozing his way into the chemistry lectures of Julius Kelp. Even Walter White and Heisenberg never had to do such frantic, panicked juggling.

Everything comes to a head in the film’s penultimate scene, the senior prom, at which Julius Kelp is a chaperone — and at which Buddy Love is slated to do the entertainment. Kelp slips away to effect his transformation and then, as Buddy mounts the stage and swings into “That Old Black Magic,” backed by Les Brown and his Band of Renown (the music in the movie is terrific), the first line of the song comes out in Kelp’s wavering croak, and from that point on the overworked formula rapidly fails and Buddy Love disintegrates in front of the entire student body (including Stella, of course), leaving the remorseful Julius Kelp holding the bag. The original transformation scene is replicated and reversed, with an awestruck crowd again staring at Lewis in absolute silence, but this time, as Kelp explains and apologizes, the incredulous faces gradually soften with sympathy and understanding, instead of the perverse repulsion/fascination response that was inspired by Buddy Love.

Julius Kelp

Why did he do it? Kelp haltingly explains:

“It happened some time ago, being a scientist, I just happened to have stumbled on one of the curious mysteries of science. I found myself so curious that I was unable to just stop. Nonetheless, I never really knew what was going to prevail. I do know now that I should have left it alone… It is a very, very hard thing to do, particularly when you found that you’ve been able to do something that so many others failed to do.”

As Buddy Love recedes, Julius Kelp’s basic decency reasserts itself:

“I can only say, I hope, I hope I haven’t hurt anyone, hurt anyone; I didn’t mean to hurt anyone, and I didn’t mean to do anything that wasn’t of a kind nature.”

And then the moral.

“Learning a lesson in life is, is never, it’s never really too late. And I think that the, the lesson that I learned came just in time. I don’t want to, I don’t want to be something that I’m not; I didn’t like being someone else.”

And looking directly at a crying Stella,

“At the same time I’m very glad I was, because I found out something I never knew — you might as well like yourself; just think about all the time you’re going to have to spend with you.”

By the end of this speech, Stella Purdy may not be the only one with tears in her eyes.

Kelp’s speech is very moving, as is ultimately the entire movie; it might be a comedy, but Jerry Lewis wasn’t just fooling around. In The Nutty Professor, he produced an original, subtle take on Stevenson’s original story. The differences between Love and Kelp are not so sharp as may at first appear; each character is implicit in the other. The bullying by the football player that starts the whole thing is actually provoked by Kelp, who speaks to the student with an arrogant superiority and biting sarcasm that Buddy Love would admire, while occasionally the shell of Buddy Love’s aggressive ego cracks and we can see the insecurity and self-loathing underneath it, the very same feelings that led Professor Kelp on to his disaster. Here the bad is not so bad and the good is not so good as to allow for easy or painless separation, and strength and weakness are not opposed, but are complimentary, just as is so often true in real life.

Stella Purdy, who knows both sides best, certainly agrees; in the film’s last shot she walks out of the chemistry classroom, arm in arm with Kelp (who now wears braces and sports Buddy Love’s haircut). They’re on their way to get married, and we can see that she has a couple of bottles of the fatal formula tucked safely in the back of her jeans. In most regards, Julius Kelp is the better man, but there are times when what you need is a little Buddy Love.

Del Moore as Dr. Warfield

Throughout his very long career, Jerry Lewis certainly showed that sometimes he could be just too much. But even his detractors must admit that in The Nutty Professor he made one of the great American comedies of the sound era, directing with brilliant invention and flair, and giving not just one great performance, but two. The cast is uniformly excellent (as Dr. Warfield, Del Moore gives what may be the funniest performance in the film — at one point you can see that he’s cracking Lewis up, and Jerry rushes through the rest of the scene to avoid completely losing it), the candy-store color scheme makes every scene pop off the screen, and the movie is full of hilarious and often surreal visual — and aural — gags and set pieces. At least one scene, where Kelp has to deal with a hangover caused by Buddy’s overindulgence the previous night and Lewis cranks the subjective sound effects up to their height, torturing the professor with screeching chalk and gum chewing, sneezing students, has to be ranked as one of the funniest in the history of film.

Mamoulian’s 1932 Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, for which Fredric March won a well-deserved best actor Oscar, is still the best “straight” version of the story, but the energy, invention, and surprise of Lewis’ take make his film a classic, and the tricky ambiguity and depth of emotion — unexpected in a comedy — ultimately make The Nutty Professor superior to all other versions of this durable fable.

Above all, Lewis must be given credit for having the courage to expose his darkest side in The Nutty Professor. Though many people assumed that Buddy Love was a just a nasty parody of Jerry’s old partner, Dean Martin, the truth is that everyone who knew his creator knew that Buddy could be no one but Jerry Lewis. (For years his wife wouldn’t allow their children to see the movie — she didn’t want them to see that side of their father.) This honesty in acknowledging his own faults gives weight and depth to Lewis’ movie, and makes what otherwise could have been just a silly, lighthearted romp a serious (and hilarious) exploration of the dark corners in all of our personalities — however many we happen to have.

What all this means is that we should have the good grace to concede that the French, in this case at least, were right after all. In The Nutty Professor, Jerry Lewis was truly magnifique, and we shouldn’t miss the opportunity to appreciate anew his great film, and say merci and au revior to a unique and irreplaceable talent.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was So You Want to Be a Movie Star – Really?.

As a Stagehand I knew Jerry in his later years. He was a bit of a project to get to know him. Jerry had a good heart, he was complicated, and he understood that he was. We were friends for twenty years, I miss him.