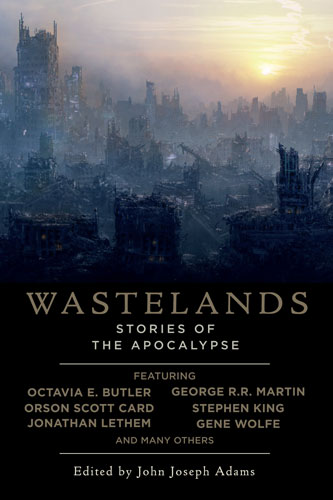

Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse, A Review

John Joseph Adams has a well-earned reputation as The Man Who Delivers Anthologies. Barnes & Noble.com has dubbed him “the reigning king of the anthology world.” By my count he’s published at least nine of them. I own one, The Living Dead, which contained enough zombie goodness (along with a few stiffs) to prompt me to buy his Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse.

John Joseph Adams has a well-earned reputation as The Man Who Delivers Anthologies. Barnes & Noble.com has dubbed him “the reigning king of the anthology world.” By my count he’s published at least nine of them. I own one, The Living Dead, which contained enough zombie goodness (along with a few stiffs) to prompt me to buy his Wastelands: Stories of the Apocalypse.

To be honest, I probably would have bought Wastelands regardless of its editor. I’m a big fan of the post-apocalyptic genre, from novels like Cormac McCarthy’s The Road or Walter Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, to films like Escape from New York or Mad Max. Why? As an inhabitant of the northeastern seaboard of the United States I’m not often confronted with existential issues. I know that I’m going to die one day and suffer separation from all that I know and love, but because civilization affords me everything I need—and much of what I want, too—I tend not to think about these issues much. The panaceas of electricity and refrigeration, and healthcare and schools, and television and the internet and books, masks the skull beneath the skin. I’m effectively insulated from the hard life and death struggle that’s woven into so much of human history. But what if it was all stripped away, and life was reduced to its essentials? That’s the question post-apocalyptic fiction asks, and one I occasionally like to ponder. With my feet up on the couch of my air-conditioned living room, of course.

You can argue that stories about primitive cultures or pre-cataclysmic swords and sorcery tales deliver the same experience, but post-apocalyptic fiction ups the ante by dealing with what has been lost, perhaps forever, and what meaning (if any) we can find in the ruins. Sort of like how the peoples of Western Europe must have felt after the fall of the Roman Empire. Post-apocalyptic fiction removes artificial constructs like law and order, and mores and polite behavior. It reduces life to base survival, and from this distillation we can deduce what’s most important.

My one sentence review is that Wastelands is in general a very solid collection that delivers on this premise. My biggest criticism is that it’s not nearly as action-packed as I was hoping. I don’t need 30 stories resembling The Road Warrior, mind you, but a couple biker battles would have been nice. The title is a bit of a misnomer as the majority of the stories are not really about the apocalypse, but about post-apocalyptic societies getting worse, or in their last stages of disintegration. I would have liked to have seen a little more meltdown, and a little less waste. Wastelands kept a personal streak going: I’ve yet to encounter the anthology in which I liked every story contained therein. Without fail every anthology contains slow spots to slog through or outright duds in which you wonder, “how did that wind up in there?” Wastelands is no exception.

My one sentence review is that Wastelands is in general a very solid collection that delivers on this premise. My biggest criticism is that it’s not nearly as action-packed as I was hoping. I don’t need 30 stories resembling The Road Warrior, mind you, but a couple biker battles would have been nice. The title is a bit of a misnomer as the majority of the stories are not really about the apocalypse, but about post-apocalyptic societies getting worse, or in their last stages of disintegration. I would have liked to have seen a little more meltdown, and a little less waste. Wastelands kept a personal streak going: I’ve yet to encounter the anthology in which I liked every story contained therein. Without fail every anthology contains slow spots to slog through or outright duds in which you wonder, “how did that wind up in there?” Wastelands is no exception.

But I for one welcome our anthology overlords. Because in the end, an anthology run by a competent editor collects good short fiction from magazines which most of us mere mortals will never be able to read. Sure, one might have a subscription to Realms of Fantasy or The Magazine of Science Fiction (Black Gate goes without saying), but what about Asimov’s Science Fiction, Jim Baen’s Universe, or Land/Space? Does anyone really subscribe to and have the time to read all these publications?

Adams did for Wastelands, and he did a solid job pulling together their best apocalyptic tales. Most of the stories were written in the last decade (Adams has a theory on why stories of the apocalypse enjoyed a renaissance in the new millennium in his introduction, which I won’t spoil here), though a few are from the 1970s, 80s, and 90s. Every story in Wastelands (there are 22) is well-written, and in the end it accomplishes what I want out of post-apocalyptic fiction: Setting a crumbling stage upon which we may consider our humanity.

Now on to my favorites.

Stephen King’s “The End of the Whole Mess,” which kicks off the volume, is the only story in this collection that I’ve previously read (it appears in Nightmares and Dreamscapes, and first appeared in Omni in 1986). I’ve always felt that King is a better short story writer than a novelist (and he’s a very good novelist) and “The End of the Whole Mess” demonstrates why. It’s a wonderful little tale with a punch of an ending that seems very much inspired by Flowers for Algernon, only much darker.

“Inertia” by Nancy Kress was another favorite. It’s about the struggles of a family living in an internment camp for carriers of an infectious skin disease. Though they live in an environment of crumbling homes and scarcities of food and other essentials, the infected on the Inside are better off than the rest of the populace on the Outside, as the world around them is torn with violence and upheaval. A doctor risks his life to make his way inside and find out why.

“The End of the World As We Know It” explores a single man’s apocalypse when his wife passes away (along with most of the rest of the world). What is he supposed to do when his anchor and sole reason for getting up in the morning dies? This story shows us, and the answer is none too hopeful.

As a junkie of all things Arthurian, “Artie’s Angels” by Catherine Wells was another favorite. Instead of noble knights on chargers we get children on refurbished Schwinns, living by a code of chivalry established by the charismatic teenage leader Artie D’Angelo. The kids try to bring order to a dark age, aka., block B9 of Kansas Habitat, in a story that very much models the rise and fall of Camelot and the Round Table.

“A Song Before Sunset” is an excellent entry about an aging survivor of the apocalypse, a former pianist who finds a concert hall while scavenging for food. He spends hours tuning up an old piano and briefly rediscovering the joy of music as a roving gang of murderous Vandals tighten the noose around him. It provides a brief glimpse of the glory that was Rome before it was overrun by barbarian hordes (the comparison seems deliberate, judging by the author’s uppercased Vandals).

“Killers” was a nasty little shocker that reminded me of McCarthy’s The Road. It’s a psychological examination of the depths we’re reduced to when consumed with constant, total war without borders.

“When Sysadmins Ruled the Earth” by Cory Doctorow was probably my favorite in the collection. Doctorow skillfully manages to portray a man employed in that seemingly most banal of jobs—a computer system administrator, or sysadmin—as a sympathetic hero. Felix Tremont refuses to abandon his post even as the world shuts down around him, one mainframe at a time. It takes you into deep into an (to me, at least) utterly foreign profession and makes the virtual realities of the internet visceral and real, and the stakes high. I can see why it won the 2007 Locus Award for best novelette.

Wastelands ends with Adams’ selected biography of post-apocalyptic fiction, a helpful guide to finding the gems amidst the detritus. Some of these titles are familiar but others are not, so I’ll likely return to it as a reference.

[…] of the most celebrated anthologies of the past few years — including The Way of the Wizard, Wastelands, Federations, Lightspeed: Year One, The Mad Scientist’s Guide to World Domination, and many […]