Wired: The Fiction Issue

I used to read Wired magazine back in the days when it was actually cool to have an email address (you had to be in academia or some tech savvy business). This was in the dark ages before web browsers and the Internet wasn’t just a place to buy stuff, host porn, post cute cat videos and spread fake news. The only people who used Apple computers were in advertising and not everyone had a cellphone; the ones who did liked to showoff by appending their email with “Sent from my Blackberry” — remember Blackberry?

I used to read Wired magazine back in the days when it was actually cool to have an email address (you had to be in academia or some tech savvy business). This was in the dark ages before web browsers and the Internet wasn’t just a place to buy stuff, host porn, post cute cat videos and spread fake news. The only people who used Apple computers were in advertising and not everyone had a cellphone; the ones who did liked to showoff by appending their email with “Sent from my Blackberry” — remember Blackberry?

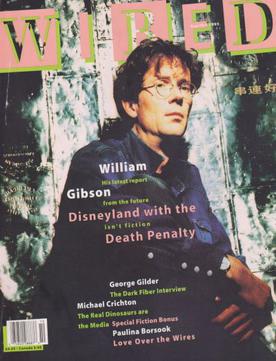

It was when I was just getting into cyberpunk, which was the magazine’s patron saint of sorts. Bruce Sterling was on Wired‘s inaugural cover and William Gibson (see below) was featured on the fourth issue (1.4 in Wired parlance). Wired was for the cultural technoliterati, the folks “wired in” (hence the title in the days well before Wi-Fi) to how computer technology was going to change the world. And, boy, did it ever.

It was also hard to read, because graphic designers thought they were making some sort of statement using odd and multiple fonts along with disorienting colors and just stuff that gave you a headache to look at but had the appearance of cutting-edge style. Fortunately, someone finally realized that jettisoning the visual clutter made it possible for people to actually read the articles instead of just being bedazzled to gaze at them. Though certain tics remain even today, like sticking a 0 in front of double digit page numbers — pagination doesn’t actually being until page 21, or as Wired likes it, 021 — in a vertical position that isn’t easy to see and mostly only on the left hand even pages. C’mon.

Somewhere about the time when the Internet stopped being an interesting forum of discussion and innovation and turned into a wasteland of constant connection and commerce, I let my subscription lapse. But this past January, Wired published its first ever all-fiction “sci-fi issue.” Despite the unfortunate terminology (which has connotations of bad adventure flicks in futuristic settings, although perhaps the disdain is just insider snobbery — do people nowadays still care and argue about such things?), I thought I’d check out the issue’s idea to, according to editor Scott Dadich, “Think about what is possible, what is plausible, what is terrifying, what is hopeful.”

Lot of plausible here with not much hopeful. Which might be terrifying were it not so close to actual experience (both psychological and technological) that today is, alas, more mundane than profound.

The problem is that, unlike fantasy where you can basically make up just about anything, the hard task for science fiction these days is to imagine something in a world that has become science fictional. How do you invoke science fiction’s classic sense of wonder when these days everyone has a Star Trek communicator advanced well beyond the capabilities envisioned by the original five year mission.

Possibly another reason for the recent outbreak of novels with themes of dystopia?

Stories by Charles Yu (how crazily self-obsessive and neurotically insecure we are for anyone who cares to listen in), Charlie Jane Anders (how constant connectedness makes us more rather than less lonely; while not an overly original premise, the angle of a therapist for robots who can’t handle human interactions is a nice touch) and Malka Older (nothing lasts forever, try as we might to make immortality scalable) all mine what is now familiar cyberpunk territory. Not a criticism, merely an observation. (As an aside to this point, while N.K. Jemsin’s “The Evaluators” is a “perils of First Contact” tale set in the 23rd century, the transcript of diplomatic missives that provides the narrative is an interstellar email thread). Twenty years ago, such speculation might invoke a sense of wonder, today it’s all too everyday familiar.

Equally familiar, but which makes it particularly highly powerful, is “Know Your Enemy” by Matt Gallagher. This is Billy Lynn’s Halftime Walk set in the sixth decade of a near-future “Forever War” (the term is from the title of Joe Haldeman’s satire of the Vietnam conflict in particular and military SF in general and still very much relevant today) where wounded veterans on a bond drive reconcile their public perception as war heroes (or villains) with whatever version of reality they choose to face (or not). Along with “The Hunger After You’re Fed” by James S. A. Corey (the pen name for Daniel Abraham and Ty Franck), make this the proverbial worth the price of the issue. The one story that is more fantasy, or perhaps magic realism is more apt, than SF, I’m not quite certain what it’s about, which is both its appeal and perhaps the authorial intention. But it does get you wondering.

Also closer to home than we no doubt already can imagine is “Hold Dear the Lamp Light” by Jay Ruben Dayrit. As you might gather from the title, this is a rumination of infrastructure and ecological disaster, in which remembering the good old days when you maybe had electricity for a couple of hours a day is a nostalgic memory; meanwhile the human condition continues on as it always has, for better and worse.

Watching Netflix on an iPad has become a common way to experience what used to be called cinema. But recall that once upon a time going to the movies was not only a communal event, but a technological wonder that initially even frightened people into thinking the black and white depiction of a train derailment was actually about to enter the theater. Glen David Gold’s hilarious spoof of The New Yorker magazine film reviews, “The Critics,” pokes fun at pretentious punditry as well as notions that just because you have the technical capability to portray something, doesn’t mean you necessarily have anything worthwhile to say.

Speaking of which, “First” by John Rogers is a throwback to the Golden Age of SF that celebrated the possibilities of technology and space travel. Which is possibly why the premise of setting a once lost Martian probe back on its original mission is not my particular cup of tea. I was also somewhat at a loss to understand why Etgar Keret’s “A.” was included. Its Twilight Zone ending (which the editorial guidelines of many a genre magazines used to warn would be rejected out of hand) contributes little to the ethical dilemmas of human cloning.

This might not be an issue you especially need to search out. But if you do run across it, worth connecting to.

A very insightful and interesting perspective presented here. Thanks for this post.

I’ve never been a huge fan of science fiction. I’ve always been more of a fantasy and horror guy. And the sci-fi I have liked in the past is usually more like fantasy in sci-fi garb (e.g. Star Wars). In addition, I don’t really know the new sci-fi stuff other than hearing a lot about dystopias.

However, I did see the recent movie Arrival based upon the story by Ted Chiang. I thought it was very interesting. But for die-hard sci-fi fans perhaps it’s “old hat,” I don’t know. But if sci-fi is more like that story/movie, I’d be more interested in reading it.

Cool article Soyka. I like the playful anecdotes about the early days of e-mail etc.

Fortunately, someone finally realized that jettisoning the visual clutter made it possible for people to actually read the articles

Heh. I subscribed back when it was still bimonthly. I did not renew because there were some passages I literally could not read due to the font and background graphic. The editor’s response to a reader’s complaint (a lot of readers complained) explicitly stated that presentation trumped content.

It’s good to know they eventually changed their mind.