Fantasia 2016, Day 17: Forging Dreams (Battledream Chronicle, the International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase, and The Dwarvenaut)

Saturday, July 30, I had hopes of seeing four shows at Fantasia. In the event, I saw three — and ended up with an interesting chat after the last one. First came an animated teen dystopia from Martinique, Battledream Chronicle, in which a young woman fights to free her homeland from digital colonialism. After that came a collection of short films, the International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase 2016 (one of the shorts being an adaptation of Ken Liu’s short story “Memories of My Mother“). Then I’d see The Dwarvenaut, a fascinating documentary about gamer and miniature-maker Stefan Pokorny that incidentally takes an interesting angle on gaming in general and Dungeons & Dragons in particular.

Saturday, July 30, I had hopes of seeing four shows at Fantasia. In the event, I saw three — and ended up with an interesting chat after the last one. First came an animated teen dystopia from Martinique, Battledream Chronicle, in which a young woman fights to free her homeland from digital colonialism. After that came a collection of short films, the International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase 2016 (one of the shorts being an adaptation of Ken Liu’s short story “Memories of My Mother“). Then I’d see The Dwarvenaut, a fascinating documentary about gamer and miniature-maker Stefan Pokorny that incidentally takes an interesting angle on gaming in general and Dungeons & Dragons in particular.

(Bad health has slowed my posting these Fantasia reviews, so as I type these words The Dwarvenaut has already debuted on Netflix. I go into more detail about the film below, but in brief: it’s a fine documentary, entertaining for a general audience and a must-watch for anyone interested in gaming and especially in the Old School Renaissance. Also, I would think, of particular relevance for anyone with an interest in fantasy. Or, for that matter, in New York City.)

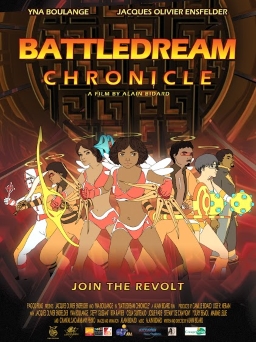

Battledream Chronicle, like Nova Seed, is a nearly one-man creation. Alain Bidard wrote, directed, and produced much of the art for the nearly two-hour film. Computer graphics make for detailed backgrounds and fluid action scenes in a science-fictional action story about young people fighting to defeat a corrupt global superpower. It’s a richly-imagined and deeply satisfying story marked by an incredible visual imagination, if also by some unusual plot choices.

In the future, countries settle disputes with gladiatorial contests in a virtual-reality game world, the Battledream, established by a mysterious force called Isfet. One country, Mortemonde, has developed a weapon that gives it unquestioned supremacy in the Battledream. Mortemonde soon conquers the rest of the planet, except for the floating city of Sablerêve, and puts the gamers now under its power to work grinding for experience points in the Battledream — a post-modern computer-gaming colonialism. Syanna Meridian and her friend Alytha Mercuri (Steffy Glissant; I can’t find a voice credit for Syanna) are two of those gamers, a team called the Syrenes de Feu, struggling to keep their heads above water. Then, after a routine combat, they stumble upon a mysterious weapon that might change the balance of power, topple Mortemonde, and bring freedom to the world. Will they survive long enough to reach Sablerêve and turn the tables on Mortemonde?

It’s an unusually rich example of the teen dystopia genre, given added power by the historical and political subtexts Bidard weaves into the story. On an obvious level, you can’t help but notice that the heroes here are largely-but-not-entirely non-white, while the colonialist forces of Mortemonde (literally “deadworld”) are largely-but-not-entirely white. More subtly, one of the themes of the movie is the way in which Mortemonde erases the history of the places they conquer; practically that means that Syanna’s story is one of self-discovery, but it also speaks to how established power validates the histories of use to it while ignoring or erasing others.

It’s an unusually rich example of the teen dystopia genre, given added power by the historical and political subtexts Bidard weaves into the story. On an obvious level, you can’t help but notice that the heroes here are largely-but-not-entirely non-white, while the colonialist forces of Mortemonde (literally “deadworld”) are largely-but-not-entirely white. More subtly, one of the themes of the movie is the way in which Mortemonde erases the history of the places they conquer; practically that means that Syanna’s story is one of self-discovery, but it also speaks to how established power validates the histories of use to it while ignoring or erasing others.

(And then there’s the name of the game weapons. As in a lot of modern games, the warriors in the Battledream summon specially-named weapons and powers. In the Battledream, the names derive from myth; at the start of the movie, for example, one of Syanna’s most powerful weapons is Soucouyant (I didn’t notice if the island from which Syanna hails is explicitly identified in dialogue as Caribbean, but it’s certainly strongly implied). The super-weapons she finds are all named for African myths, specifically for Egyptian gods; I’m reminded of the ideas of Cheikh Anta Diop and others about the cultural unity of Egypt and elsewhere in Africa, again evoking the idea of suppressed histories. I’ll note that the malign Isfet is from Egyptian myth, as well.)

The film fuses subtext and plot masterfully, giving the armature of plot twists and heroic deaths and action scenes unusual resonance. It’s impossible not to be struck by Syanna swearing to “kill the master inside of them, and the slave inside of me.” By the end there’s a well-earned epic feeling to the story, a sense that this particular tale of a young person struggling against the injustice of the world around them grows out of history and speaks back to it.

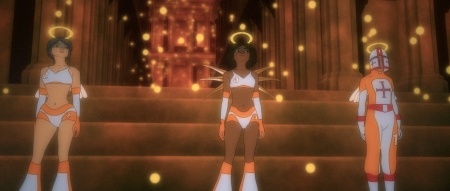

That epic feel also comes from the depth of imagination at work in the film. Battledream Chronicle in fact imagines a highly detailed and wildly original world, with distinctive settings and backgrounds. Surprisingly, the virtual world of the Battledream doesn’t vary much from fight to fight — it’s a collection of vast empty halls, architecturally fascinating but repetitive. That’s a good choice, as the backgrounds don’t distract from the action scenes. In contrast, though, everything in the real world is intensely designed: particularly in floating Sablerêve, even everyday objects like a chair or table has a distinctive visual identity. There’s a Kirbyesque prodigality of imagination mixed with a more Mobius-like stylistic sensibility; it works wonderfully.

That epic feel also comes from the depth of imagination at work in the film. Battledream Chronicle in fact imagines a highly detailed and wildly original world, with distinctive settings and backgrounds. Surprisingly, the virtual world of the Battledream doesn’t vary much from fight to fight — it’s a collection of vast empty halls, architecturally fascinating but repetitive. That’s a good choice, as the backgrounds don’t distract from the action scenes. In contrast, though, everything in the real world is intensely designed: particularly in floating Sablerêve, even everyday objects like a chair or table has a distinctive visual identity. There’s a Kirbyesque prodigality of imagination mixed with a more Mobius-like stylistic sensibility; it works wonderfully.

But more generally, the technology and societies of the movie are distinctive and well-dramatised. The relationships, and the kinds of relationships fostered in different places, come across remarkably well: the family and friends of Syanna’s home, for example, contrast strongly with the hierarchies of Mortemonde and its culture in which people rise based on their ability to betray and corrupt others. That latter ought to come off as cardboard villainy, but it doesn’t, quite; it feels too true, too much like how the world works (or at least a part of the world). And then again in Sablerêve things are looser, the people more respectful of each other.

Beyond the cultures, the individual characters come alive. You see what’s shaped Syanna, and relate to her strength of will. She’s not an idealist, except insofar as the practicalities of her life have taught her what’s right and what’s wrong. Her character fits perfectly in a story about the corruption of power, and in fact brings out the core idea of any story about a young person struggling against a dystopic future: youth must redeem the corrupted world shaped by old age and fallen history. The revolutionary against the system, in the form of someone young enough to think the revolution is enough, that a revolution will end history and create paradise. Here, that actually makes sense thematically: Mortemonde has rewritten history, so to defeat them really is to defeat history, to undo a distorted version of truth.

Having said all of this, there are a couple of criticisms worth making. To start with, the plot has a bit of an odd structure; the ultimate weapon that Syanna finds, supposedly the only way to defeat Mortemonde, doesn’t actually play as big a role in the climax as one might expect. More seriously, the character designs have a disturbing similarity of body type. The characters are highly individualised, not just ethnically varied but with facial designs and stances that imply their characters at a glance. So it’s notable that they all tend to be slim, and the girls busty. That in turn is brought out by one of the worst cases of sexually dimorphic body armour I’ve ever seen: males fully covered neck to toes and often with full helmets, les Syrenes de Feu in bikinis and boots. (To see what I mean, look at the image at left.)

Having said all of this, there are a couple of criticisms worth making. To start with, the plot has a bit of an odd structure; the ultimate weapon that Syanna finds, supposedly the only way to defeat Mortemonde, doesn’t actually play as big a role in the climax as one might expect. More seriously, the character designs have a disturbing similarity of body type. The characters are highly individualised, not just ethnically varied but with facial designs and stances that imply their characters at a glance. So it’s notable that they all tend to be slim, and the girls busty. That in turn is brought out by one of the worst cases of sexually dimorphic body armour I’ve ever seen: males fully covered neck to toes and often with full helmets, les Syrenes de Feu in bikinis and boots. (To see what I mean, look at the image at left.)

That’s too bad, because otherwise Battledream Chronicle is an extremely entertaining and powerful film. It’s well-structured and a feast for the eyes, with excellently staged action scenes in and out of virtual reality. The world’s both a dreamlike play with history and also a fine science-fictional imagining, with sky cities hovering above environmental degradation and colonial overlords. And it is, in the end, an excellent story that mixes adventure with very rich themes.

From the Hall Theatre, where Battledream Chronicle was playing, I crossed the street to the De Sève for another of Fantasia’s short film showcases. This one was the International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase, promising movies from North America, Australia, and Estonia. Last year’s version of the showcase had been a solid collection of stories that had reminded me of science fiction on the cusp of the 1960s New Wave. This year’s collection seemed to have moved forward more wholly into the New Wave, in the way that unusual narrative structures and profoundly science fictional elements explored and brought out aspects of human character.

From the Hall Theatre, where Battledream Chronicle was playing, I crossed the street to the De Sève for another of Fantasia’s short film showcases. This one was the International Science Fiction Short Film Showcase, promising movies from North America, Australia, and Estonia. Last year’s version of the showcase had been a solid collection of stories that had reminded me of science fiction on the cusp of the 1960s New Wave. This year’s collection seemed to have moved forward more wholly into the New Wave, in the way that unusual narrative structures and profoundly science fictional elements explored and brought out aspects of human character.

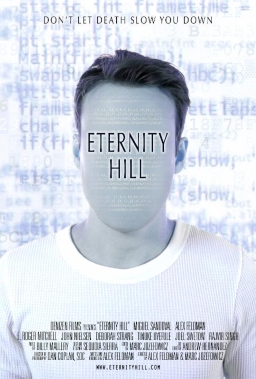

The first film was the 16-minute “Eternity Hill,” directed by Marc Josefowicz and Alex Feldman; Feldman also wrote and starred. In the future, an unusual service creates holographic replicas of the dead called denizens, using near-AI-level computers to integrate photos and writings into a replica personality. But the business behind the denizens, Eternity Hill, is under financial pressure and its survival might rest with one particular denizen.

The idea’s strong, and the piece is well-acted; particularly memorable are scenes in the all-white chamber where the replicas meet the living friends and family of their originals. But I didn’t feel the film worked overall. Although the story was well-structured, with an arresting beginning and a solid twist to the ending, the nature of the technology seemed half-developed. I wondered about other applications of the algorithms behind the denizens of Eternity Hill — would historical figures be re-created, would people use it to make versions of themselves, and so on and so forth. None of that is relevant to the story at hand, but the lack of even a throwaway line to address it was disconcerting, tending to undermine my sense of the imagined future. I wondered how much the story really meant, and what the actual place of Eternity Hill was; what the stakes here really were.

Next came “Ingrid and the Black Hole,” written and directed by Leah Johnston. A powerful story that packs a considerable emotional punch into its 7-minute running time, it opens with a girl and a boy gazing at the stars; the girl speculates about black holes and relativity and time machines, and then the film moves back and forth through moments of their lives. Character is sketched in briefly but effectively, as a life comes alive in moments, woven in with astronomy and theories of time travel.

The camera moves across years in long travelling shots, and different times are made to combine in an elegant metaphor that only becomes clear near the end. I saw what was happening a few seconds before the film spelled it out, and then, marvelously, the film kept going to find a heart-rending ending moment. It would, I think, have been easy to end with the revelation; that “Ingrid and the Black Hole” did not is an example of the many strong choices throughout the movie, and also of its deft understanding of emotional structure. What is most notable is the way in which the handling of time doesn’t distract from character or from the film’s emotional effect, but only adds to it so that the final shot is almost unbearably moving. It was by far the most touching of all the films I saw that day, and indeed perhaps the most of any film I would see at Fantasia.

The camera moves across years in long travelling shots, and different times are made to combine in an elegant metaphor that only becomes clear near the end. I saw what was happening a few seconds before the film spelled it out, and then, marvelously, the film kept going to find a heart-rending ending moment. It would, I think, have been easy to end with the revelation; that “Ingrid and the Black Hole” did not is an example of the many strong choices throughout the movie, and also of its deft understanding of emotional structure. What is most notable is the way in which the handling of time doesn’t distract from character or from the film’s emotional effect, but only adds to it so that the final shot is almost unbearably moving. It was by far the most touching of all the films I saw that day, and indeed perhaps the most of any film I would see at Fantasia.

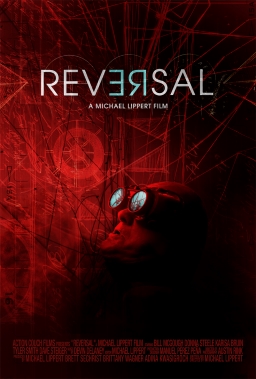

“Reversal,” written and directed by Michael Lippert, is another time travel story, but a completely different one. An obsessed man (Bill McGough) tries to perfect a time machine that will take him back to the past to save his wife (Donna Steele) from an armed robber. The time machine, though, is based on an old film projector, which tends to overheat at unpredictable moments and pull him back to the present. Will he succeed in saving his wife, or will they all burn up like so many combustible old film reels?

The story here is fine, and the central metaphor that propels it is wonderful. A film, like any work of art, has the characteristic of a time machine that can pull viewers back to the moment they first experienced it. And, like much narrative art, it also gives the illusion of controlling time: watch a film over again, and you’re replaying the same moments. Skip ahead or back, and you travel forward or backward in time. I did think that metaphor could have been enlarged on rather more in the film itself, but the story’s well structured and ends on a very strong note.

The story here is fine, and the central metaphor that propels it is wonderful. A film, like any work of art, has the characteristic of a time machine that can pull viewers back to the moment they first experienced it. And, like much narrative art, it also gives the illusion of controlling time: watch a film over again, and you’re replaying the same moments. Skip ahead or back, and you travel forward or backward in time. I did think that metaphor could have been enlarged on rather more in the film itself, but the story’s well structured and ends on a very strong note.

“F Meat,” directed by Sean Bell from a script by Bell and Jeremiah Galea, is an 18-minute movie set in a cyberpunk-ish future, about a former political radical, Smit, who has become the surprising choice to take over control of a major corporation. The corporation makes much of its money on a miracle food, F Meat. The current chief, Fielding, has summoned the radical to his underground office to explain why Smit has been selected to take over. Smit doesn’t understand it himself, and is shocked to find himself imprisoned in the office as he’s faced with a terrible moral choice about the nature of F Meat.

This was an odd film in that a lot of individual pieces didn’t work but the movie still succeeded anyway, or nearly so. The secret of F Meat is easy to guess, but makes no particular sense. The two leads overact, but then one can argue they had no choice as they had to get across the deeply personal aspects of a script that otherwise might have played as a dry moral thought experiment. For all this, the film’s interesting to watch, as it’s visually stylised. The drama is clear, with a ticking clock and an obvious dilemma facing one character — while another’s made to question what he’s always accepted as good. The final twist setting up the ending is predictable, but I think in the end what makes the story work is the plausible-sounding arguments given to the man who has to defend the apparently indefensible. It’s not so much that the arguments are convincing, although at a certain level they are challenging, but that they show how, in the words of Upton Sinclair, “it is difficult to get a man to understand something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

Next came “Beautiful Dreamer,” directed by David Gaddie from a script by Gaddie and Steven Kelleher, based on Ken Liu’s story “Memories of my Mother.” In the middle of the twenty-first century, a woman who has a terminal disease (Jo Armeniox) leaves her husband (Theis Weckesser) and young daughter Amy (Lila Taylor) to go into space aboard a ship that moves at near-light speeds. Relativistic effects mean that she hardly ages, extending her life so she can visit her daughter every seven years. We see some, though not all, of these reunions; the mother stays the same age, curiously eternal though doomed to die, while her daughter grows old and the world around her changes. The logical conclusion is both inevitable and affecting.

This is a wonderful character-centred science fiction film. The core idea is quintessentially science fictional, but the point is the effect of that conceit on the characters over the course of their lives. It’s an examination of a mother-daughter relationship given a whole new angle by conceivable-but-futuristic technology. So it’s also a generational saga; and again from a science fictional angle. Computer effects are well-chosen, with animated holographic holographs here and a robot nanny there and, in the beginning, a looming space elevator in the background; it all builds the sense of a world, and one that changes over time. Dialogue is very effective, tersely getting at character and passing time, and the acting is very good; Natalie Smith, as the most-often-appearing adult Amy, deserves special mention here. Presenting such an odd mother-daughter connection in a way that reads as immediately emotionally true must have been a challenge, but it’s performed very well. It’s a strong exploration of family bonds, of what the relationship of parent and child is, and, in the end, how we all must move on to face the future.

This is a wonderful character-centred science fiction film. The core idea is quintessentially science fictional, but the point is the effect of that conceit on the characters over the course of their lives. It’s an examination of a mother-daughter relationship given a whole new angle by conceivable-but-futuristic technology. So it’s also a generational saga; and again from a science fictional angle. Computer effects are well-chosen, with animated holographic holographs here and a robot nanny there and, in the beginning, a looming space elevator in the background; it all builds the sense of a world, and one that changes over time. Dialogue is very effective, tersely getting at character and passing time, and the acting is very good; Natalie Smith, as the most-often-appearing adult Amy, deserves special mention here. Presenting such an odd mother-daughter connection in a way that reads as immediately emotionally true must have been a challenge, but it’s performed very well. It’s a strong exploration of family bonds, of what the relationship of parent and child is, and, in the end, how we all must move on to face the future.

Next was a short piece, the 3-minute “Alternate,” directed and written by Conor Holt. A man in a desolate apartment (Al Odden) puts on a VR headset and explores other lives. The film’s based on the gap between reality and fantasy, between one’s own life and the ones imagined; and about how difficult it can be to escape escaping.

Finally came “Take Off,” directed and written by Carlos Eduardo Lesmes López. An astronaut is left behind by his mates on an alien world. With limited resources he seems to be doomed — but he finds a portal, a very small one, back to Earth. He can’t cross over, though, only speak and send very small objects across the void. Luckily, there’s someone on the other side. Perhaps unluckily, that someone is a small girl, who is skeptical of the voice she hears.

The short builds up nicely to a final monologue from the astronaut, a cosmic and personal speech that gets at the main theme of the film: the vastness of the universe, the need for connection. It’s not surprising, but it is well done. The central device is improbable, but it’s not so impossible that it breaks the movie; one accepts it as literalised metaphor and moves on. As I said, here as elsewhere I felt like I was seeing a story with a sensibility reminiscent of the New Wave: science fiction as a source of imagery, as a way to get at human and visionary truth.

After the screening there was a question-and-answer session with Leah Johnston, director of “Ingrid and the Black Hole,” Michael Lippert, director of “Reversal,” Sean Bell and Jeremiah Galea, respectively writer and director of “F Meat,” and David Gaddie and Steven Kelleher, the director and writer of “Beautiful Dreamer.” (As always, the following comes from handwritten notes taken on the fly, and may contain errors.) The first question went to the makers of “F Meat,” about what the product name “F Meat” stood for. They said that during the making of the film they asked the crew members individually what they thought it meant, and each person had a different answer. The director thought it stood for “Fielding,” the name of the creator.

After the screening there was a question-and-answer session with Leah Johnston, director of “Ingrid and the Black Hole,” Michael Lippert, director of “Reversal,” Sean Bell and Jeremiah Galea, respectively writer and director of “F Meat,” and David Gaddie and Steven Kelleher, the director and writer of “Beautiful Dreamer.” (As always, the following comes from handwritten notes taken on the fly, and may contain errors.) The first question went to the makers of “F Meat,” about what the product name “F Meat” stood for. They said that during the making of the film they asked the crew members individually what they thought it meant, and each person had a different answer. The director thought it stood for “Fielding,” the name of the creator.

One audience member asked about the use of time travel, and whether it represented any sort of trend, and if so whether it spoke to a sense of nostalgia. Lippert suggested it spoke to our connection to ideas, and the amount of things to worry about in the present. Kelleher said that science fiction lends itself to that kind of reflexive exploration, citing Solaris. Gaddie said it might have to do with a sense of fear about technology, of the present moment and of the future. Another questioner asked about the different approaches to the theme of time in “Ingrid” and “Beautiful Dreamer,” to which Johnston said it was cool to see her film in the context of films about time. She spoke about how her film used black holes as a metaphor for a different human experience of time, and that while films often viewed people from the outside she’d wanted to capture an internal sense of peace. Gaddie observed that while we don’t all experience relativistic effects, time does move differently for different people. Children age quickly, which can cause their parents to have a sense as though travelling through time.

The “Beautiful Dreamer” team was asked about a robot that appeared briefly in a scene set in a park, and the director said that it was actually a late digital addition to the film, when he realised that there needed to be a presence in that scene establishing that a mother had not left her child on her own without a guardian. Johnston was asked about the way she accomplished some of the long, complex shots, and she said that while she’d hoped to to do it all in-camera, the budget dictated handling it in post-production with the result that a relatively brief film had 180 FX shots in it (including digital age make-up). The directors were then asked how many days it took to shoot the different films; “Reversal” took 5 days, “F Meat” took 4, “Ingrid” was done in 3, and “Beautiful Dreamer” in 5.

I asked the “Beautiful Dreamer” team about the process of adapting the Liu story, and how it came about. Gaddie said he’d reached out to Liu about another story, and though that didn’t work out Liu sent him some other works to look at, “Beautiful Dreamer” among them. It took some time to put together. Liu has said it was interesting to see the adaptation, and how the film kept the essence of the story. Gaddie said he’d added only a scene or two to the original and expressed bafflement at how a 2-page short story ended up a 26 minute film.

That ended the questions. Next for me came another film at the De Sève, a documentary about model-making, art, determination, Brooklyn, and role-playing games, among many other things.

That ended the questions. Next for me came another film at the De Sève, a documentary about model-making, art, determination, Brooklyn, and role-playing games, among many other things.

The Dwarvenaut is a film about Stefan Pokorny, the founder and creative force behind Dwarven Forge, a company that makes high-quality miniatures and terrain for tabletop role-playing games. The movie, directed by Josh Bishop with writing credits given to Bishop with Victoria Lesiw and Nate Taylor, loosely follows Pokorny’s third Kickstarter campaign. Pokorny wants to create a miniature set depicting a vast city, Valoria, originally imagined by Pokorny for his homebrew D&D campaign world. In order to have the money to make the city, and recoup his investment in time and resources to develop it, Pokorny needs two million dollars. Will he get it?

The movie mostly takes place during the month of the Kickstarter, with extended flashbacks to show Pokorny’s life up to that point. But The Dwarvenaut is less about gaming or about crowdfunding than about Pokorny struggling to realise his vision. It’s a story about the making of an artist, in which gaming provides a form for his art. Perhaps the clearest sign of the movie’s success is that it is itself inspiring, giving energy and a sense of possibility to its audience.

It’s visually quite effective, with some excellent close-in shots of Pokorny’s miniatures. Lighting and mists help further evoke a sense of the world, which has what by gaming standards seems an old-school feel: the sense of a solid wood-and-stone medieval city infested with monsters, as opposed to the elaborate magic-based societies of later Dungeons & Dragons editions. These shots are particularly vital, not just showing us Pokorny’s art but also how his imagination works — and setting up a theme that runs through the film, about the power of cities.

Pokorny grew up in New York, where his adoptive parents lived, and is based in Brooklyn. The movie makes great use of the setting, showing us Pokorny’s company moving to a new studio but also showing the environment around it, creating a sense of place to match the places Pokorny imagines. We get voice-overs from Pokorny about the importance of cities in fantasy gaming, and if that’s something that’s been long-established in fantasy fiction and D&D from Gygax’s City of Greyhawk to Ed Greenwood’s Waterdeep to the adaptation of Fritz Leiber’s Lankhmar, we understand that the point is that there’s a direct parallel between Pokorny as a New Yorker and the sprawling city of Valoria that he imagines and designs in his work.

It’s part of a larger theme of the parallels between life and art. Pokorny creates art, fictional architecture, basd on actual medieval and renaissance structures that he’s studied. But just as he imagines these things as the basis for the quest-stories played in the games of himself and others, so the film itself takes on the structure of a quest, following the Dwarven Forge move and the Kickstarter and even a trip to GaryCon.

It’s part of a larger theme of the parallels between life and art. Pokorny creates art, fictional architecture, basd on actual medieval and renaissance structures that he’s studied. But just as he imagines these things as the basis for the quest-stories played in the games of himself and others, so the film itself takes on the structure of a quest, following the Dwarven Forge move and the Kickstarter and even a trip to GaryCon.

This is a story about art, about inspiration and creative energy. Pokorny carries the piece as a creative force, a man almost possessed by inspiration, overflowing with enthusiasm and energy. There is little critical evaluation of his art, either as sculpture or as gaming product. That’s not really the point. It’s about the transmogrification of experience into art.

Perhaps as a result, there are some odd choices. It is mentioned a couple of times that Pokorny is and has been a heavy drinker, once in a discussion of his teen years and once in a confrontation with another gamer at GaryCon. But that narrative strand’s never followed up. And due to the movie’s focus on Pokorny, other people at Dwarven Forge are sidelined — which is understandable, but it would have been interesting to have a bit more of a sense of the growth of the company. For that matter, the move undertaken in the course of the Kickstarter campaign is oddly underplayed; you’d expect there to be logistical headaches given everything else going on, but there isn’t much made of that.

Most importantly, the Kickstarter campaign itself is left very vague. There isn’t much of an explanation of what Pokorny did to move the needle with his backers. The campaign is a constant drumbeat through the movie, always so much time left to raise so much money, but there’s no sense of what Pokorny’s plans are to raise funds other than making the occasional video. I don’t mean that the movie should have focussed on the ins and outs of running a Kickstarter campaign, only that given the significance of the campaign to the structure of the film, a bit more information would have helped create a more dramatic shape.

Most importantly, the Kickstarter campaign itself is left very vague. There isn’t much of an explanation of what Pokorny did to move the needle with his backers. The campaign is a constant drumbeat through the movie, always so much time left to raise so much money, but there’s no sense of what Pokorny’s plans are to raise funds other than making the occasional video. I don’t mean that the movie should have focussed on the ins and outs of running a Kickstarter campaign, only that given the significance of the campaign to the structure of the film, a bit more information would have helped create a more dramatic shape.

Of course one can argue that the Kickstarter is to be read as more of a background element. Certainly there’s a sense that the primary interest of the film is in Pokorny and his eccentric kind of art. It’s about his need to realise his art, and the journey he takes over the course of his life. It’s about his development as an artist and how his art reflects everything he is.

It is also, however indirectly, about gaming. Or at least it’s informed by gaming. I don’t think non-gamers will be alienated by anything in the film; for them it’s a glimpse of a particular world and a particular community. Veteran gamers will appreciate what they see when Pokorny runs a game, will understand how his creations can be used in gaming, perhaps will know the term ‘grognard.’ They may also have more of an appreciation of the scenes from GaryCon and GenCon, and be more interested in an interview with Frank Mentzer. I note also a touching moment when Pkorny and friends pass by Gary Gygax’s old house with all the awe of pilgrims visiting a shrine. I can relate: having grown up with D&D and Dragon Magazine in the 80s when then-publishers TSR was based out of Lake Geneva, Wisconsin, seeing the place on screen was fascinating.

Art and gaming come together in the film: Pokorny’s shown running a game, caught up in the inspiration of the moment. Elsewhere he argues for the importance of gaming, for Dungeons & Dragons as a co-operative endeavour, as a way to learn about the character of oneself and others. To find out what you’d do in a given situation, what choices you’d make if you were caught up in a specific story. There can’t help but be a reflexive sense here, as we learn about Pokorny’s own character by the choices he makes and has made in his life. Here as elsewhere the line between gaming, art, and life blur to nothing.

Art and gaming come together in the film: Pokorny’s shown running a game, caught up in the inspiration of the moment. Elsewhere he argues for the importance of gaming, for Dungeons & Dragons as a co-operative endeavour, as a way to learn about the character of oneself and others. To find out what you’d do in a given situation, what choices you’d make if you were caught up in a specific story. There can’t help but be a reflexive sense here, as we learn about Pokorny’s own character by the choices he makes and has made in his life. Here as elsewhere the line between gaming, art, and life blur to nothing.

The Dwarvenaut’s an entertaining and inspiring movie about a popular artist in an unusual field. It’s full of oddity, but also presents a fair sense of Pokorny’s life. Visually striking, it captures a sense of place, but more than that, it tells a story about the importance of art and how, if life shapes art, the reverse is also true.

A question-and-answer session followed with director Josh Bishop and Pokorny himself. Asked how the two met, Bishop said that he was introduced by the editor of his previous film to the creative designer of Pokorny’s Kickstarter videos. There had originally been talk of doing a reality TV show around Pokorny, but Bishop thought Pokorny was a movie, not just a TV program. Pokorny was asked about D&D as a means for self-expression; Pokorny asked who in the audience had played the game, and almost everyone in the theatre raised their hand. He said that he liked the co-operative nature of the game and the group imagination that emerges; how no-one knows what’s going to happen. Bishop added that he thought it was an interesting psychology lesson, a way to see what goes on in people’s heads.

Asked about what he thought of Kickstarter and why he keeps going back to the platform, Pokorny said he had no idea, and that he swears off Kickstarter after each campaign — the same, he said, as he swears off Burning Man after each year. He then said that stressful as it is, it’s fun; and at this point his company needs it. He has a few thousand regulars by this point, and each campaign is getting increasingly complicated. Bishop added that one of the virtues of Kickstarter is that it’s a way to raise funds without relinquishing creative control of a project. Pokorny then said that at this point he feels he’s getting old, having been in business for 20 years, and now sees younger people with more energy. But he’s inspired by his backers to keep going.

Asked about the sense of place and of Brooklyn created in the film, Bishop said that he had definitely wanted to make the place a character, and found he didn’t really have to do anything beyond make the film for that to happen. Pokorny added that Bishop just followed him around as he hung out all over Brooklyn. He spoke about the renaissance of tabletop gaming, and how he hoped the film could push the wave and show more of the world about D&D; Pokorny recalled the years of Satanic panic around the game, and now hoped to show it as a game of co-operation.

Asked about the sense of place and of Brooklyn created in the film, Bishop said that he had definitely wanted to make the place a character, and found he didn’t really have to do anything beyond make the film for that to happen. Pokorny added that Bishop just followed him around as he hung out all over Brooklyn. He spoke about the renaissance of tabletop gaming, and how he hoped the film could push the wave and show more of the world about D&D; Pokorny recalled the years of Satanic panic around the game, and now hoped to show it as a game of co-operation.

Pokorny was asked how he combined business and art, whether he felt burnt out or forced to compromise. Pokorny said no, and remembered that he hadn’t thought he could make money from playing D&D. He said he was now “all in” on Dwarven Forge artistically. While he tries to imagine what gamers would like, he balances that with indulgence of his own artistic whims. Claiming not to be too smart, he observed that running a business is a complex process. You have, he said, to push hard, almost lose your mind, even torture yourself — but as an artist you drive yourself through the process. Finally, asked about his next Kickstarter, he said he’d be revisiting dungeons and caverns, which he’d already designed early in his company’s life, but that he’d be adding elements of a city and castles. Work had already begun, and the Kickstarter should be launching in March.

That ended the question-and-answer period. What happened next was a little complicated. I went across the street to see if I’d be in time to catch the movie that was playing at the Hall theatre (a Japanese romantic comedy about manga, Bakuman). Unfortunately, I wasn’t; it had already begun, and after a moment inside the theatre I decided I’d rather not try to write a review based on a partial viewing. Coming out of the theatre I saw Pokorny and Bishop speaking to people from the festival in the atrium of the Sir George Williams building, where the Hall’s located. I went back across the street to the De Sève to see if I could get into the film playing there, Operation: Avalanche. The only seats available were in the front row, and rather than strain my neck I decided to catch the film’s second showing, the next afternoon. Left with nothing else to do, I wandered back across the street to see if I could ask Pokorny about something I’d noticed in the film.

He turned out to be not just easy to talk to but instantly friendly, as energetic and enthusiastic as he’d come across on screen. As we talked, his party set out for a nearby bar, and I tagged along at his insistence. I’d noticed that, although I tended to associate miniatures with the fourth edition of D&D, all the rulebooks shown onscreen were the orange-spined First Edition rules. He enthusiastically affirmed that he only played First Edition: “that’s what Gygax intended!” He made miniatures not for the sake of a specific ruleset, but just because he’d begun by playing alone, with a group not part of the larger gaming community, and they’d found the miniatures useful and fun. He still seemed to feel not entirely a part of the old-school community, for all his time in the gaming world and his attendance of conventions and his familiarity with many of the figures of the Old School Renaissance.

I don’t drink, so I accompanied Pokorny and his party to the bar and then left. It had been a fine day, another day with much food for thought about genre. I’d seen a lot of things on screen that I hadn’t seen before, a lot of distinctive visions brought out through genre frameworks. It was a day that emphasised the freedom that genre can give a storyteller. The next day, on the other hand, would show something different.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia 2016 diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.