Robert E. Howard: The Barbarians

In the opening pages of The Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye introduced a theory of modes, of types of stories, based on the power of action held by a story’s hero. If the hero has powers superior in kind to other characters, the story is a myth; if the hero has powers superior in degree, like a Launcelot or a Charlemagne, then the story’s a romance (in the old sense of a fantastic adventure story). A hero superior to other characters but not to the world around him is a leader, the kind of protagonist you might have in an epic or a tragedy, like Macbeth or Odysseus, and so belongs to the high mimetic mode: a mode imitating life, but at a higher pitch than life is commonly lived. A hero “superior neither to other men nor to his environment” impresses us with a sense of shared humanity, and exists in the low mimetic mode. A hero with less power or agency than ourselves creates the ironic mode, a story about “bondage, frustration, or absurdity.”

In the opening pages of The Anatomy of Criticism, Northrop Frye introduced a theory of modes, of types of stories, based on the power of action held by a story’s hero. If the hero has powers superior in kind to other characters, the story is a myth; if the hero has powers superior in degree, like a Launcelot or a Charlemagne, then the story’s a romance (in the old sense of a fantastic adventure story). A hero superior to other characters but not to the world around him is a leader, the kind of protagonist you might have in an epic or a tragedy, like Macbeth or Odysseus, and so belongs to the high mimetic mode: a mode imitating life, but at a higher pitch than life is commonly lived. A hero “superior neither to other men nor to his environment” impresses us with a sense of shared humanity, and exists in the low mimetic mode. A hero with less power or agency than ourselves creates the ironic mode, a story about “bondage, frustration, or absurdity.”

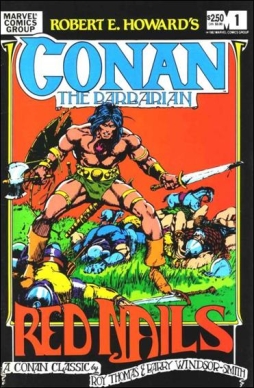

Frye has a lot more to say about all these different modes, but that’ll do for a start. I’ve been thinking about Frye and his theory of modes with respect to Robert E. Howard and to Howard’s three great barbarian heroes: Kull, Conan, and Bran Mak Morn. It seems to me that the theory of modes helps to explain the substantive difference between the three characters; why their stories, as far as I’m concerned, feel so different one from another. All of them are characters of the romance mode, but a story in one mode can be pulled toward another, and I think that’s what’s happening with these characters.

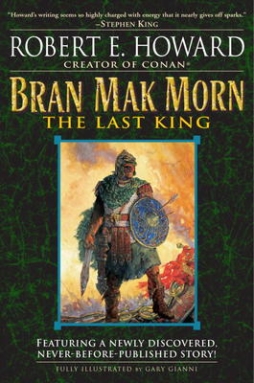

Look at Bran Mak Morn, the king of Picts struggling against the might of Rome. The Picts are the quintessential Howardian barbarian people, at the edge of history and language, violent and in some way irredeemable — if redemption could even be said to exist for Howard. The Picts are red of tooth and claw, fighting the ‘civilising’ mission of Rome. Unlike the other two characters, Bran’s caught up in recorded history. He might even be said to be struggling unsuccessfully against history; a 1930 story established that Bran died in battle, his aspirations to return his people to greatness unsatisfied. But a few years before, “Men of the Shadows,” the first complete Bran story, establishes the tragic mood, reciting the history and decay of the Picts. Bran is a throwback to an era when the Picts were great, but is doomed to fail at dragging his people up to his level: “In the dim mountains of Galloway shall the nation make its last fierce stand. And as Bran Mak Morn falls, so vanishes the Lost Fire — forever. From the centuries, from the eons.”

Look at Bran Mak Morn, the king of Picts struggling against the might of Rome. The Picts are the quintessential Howardian barbarian people, at the edge of history and language, violent and in some way irredeemable — if redemption could even be said to exist for Howard. The Picts are red of tooth and claw, fighting the ‘civilising’ mission of Rome. Unlike the other two characters, Bran’s caught up in recorded history. He might even be said to be struggling unsuccessfully against history; a 1930 story established that Bran died in battle, his aspirations to return his people to greatness unsatisfied. But a few years before, “Men of the Shadows,” the first complete Bran story, establishes the tragic mood, reciting the history and decay of the Picts. Bran is a throwback to an era when the Picts were great, but is doomed to fail at dragging his people up to his level: “In the dim mountains of Galloway shall the nation make its last fierce stand. And as Bran Mak Morn falls, so vanishes the Lost Fire — forever. From the centuries, from the eons.”

There’s a bleakness, a futility, to Bran Mak Morn that’s only implicit, at most, in Kull and Conan. Certainly he make a sort of compromise, in “Worms of the Earth”, that the other two perhaps could not. So Bran inclines toward the high mimetic, toward the condition of tragedy.

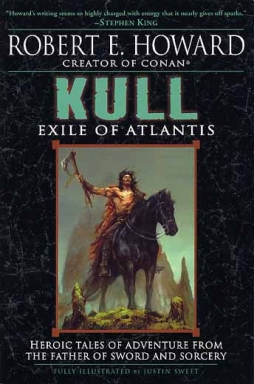

There is a tragic aspect to Kull, as well; he’s the King of Atlantis, and we know what happens to Atlantis. But the stories seem to me to largely forego any foreshadowing of cataclysm. Kull’s a king in the best traditions of romance; like Arthur, he has a thirst for seeing wonders, and so he will go for himself to see “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune”, or the cat of Delcardes in “The Cat and the Skull”. In a rage, he will lead hundreds of men after a fleeing noble in order to avenge an insult, even beyond the edge of the world — but there the story draft ends (it doesn’t even have a title), and we are left, in one of the most frustrating fragments in literary history, with the image of the king being ferried by the prototype of Charon across the river to the land beyond the sunrise beyond which “is magic and the unknown.”

Kull is definitely greater than Bran; it is to Kull that Bran turns for aid against a Roman army in the story “Kings of the Night”. Bran is the descendant of Kull’s lieutenant, not of the king himself. It is Kull who is in the thick of the fighting, against impossible odds, while it is Bran who leads the surprise charge that ends the battle almost too late. Kull disappears just as he is surrounded by a score of enemies; Bran remains, to face the recriminations of his allies for his delay in leading the charge. Kull returns to legend and the abyss of time, while Bran’s victory “is a thing no more solid than the foam of the bright sea.”

But if we can contrast Kull and Bran by seeing the two of them together in one story, we can contrast Kull and Conan from observing the differences between the Kull story “By This Axe I Rule!” and the Conan story “The Phoenix on the Sword”, the rewritten form of the Kull tale. “By This Axe” begins by showing us a conspiracy against Kull; then shows us Kull himself, complaining about the difficulties of being king and the boundaries set upon his power by traditions. Kull hears the complaint of a young noble who wishes to marry a woman forbidden him by the customs of his people; Kull wants to help, but his counsellors tell him that he cannot violate the customs. An interlude follows where the weary Kull meets the beloved woman. Then, later that night, the conspirators strike. Kull kills them, and in so doing regains a measure of vigour — he commands that tradition be overruled, and the marriage be allowed: “I am the law!” he cries.

But if we can contrast Kull and Bran by seeing the two of them together in one story, we can contrast Kull and Conan from observing the differences between the Kull story “By This Axe I Rule!” and the Conan story “The Phoenix on the Sword”, the rewritten form of the Kull tale. “By This Axe” begins by showing us a conspiracy against Kull; then shows us Kull himself, complaining about the difficulties of being king and the boundaries set upon his power by traditions. Kull hears the complaint of a young noble who wishes to marry a woman forbidden him by the customs of his people; Kull wants to help, but his counsellors tell him that he cannot violate the customs. An interlude follows where the weary Kull meets the beloved woman. Then, later that night, the conspirators strike. Kull kills them, and in so doing regains a measure of vigour — he commands that tradition be overruled, and the marriage be allowed: “I am the law!” he cries.

You can see elements of this framework in the Conan version, but it’s also quite different. The story begins in much the same way, but even before we get to the story proper we have an excerpt from some unknown chronicle history, telling us of “an age undreamed of,” and of a conqueror named Conan, who came “with gigantic melancholies and gigantic mirth, to tread the jeweled thrones of the Earth under his sandalled feet.” So in contrast to the Atlantean Kull and Bran the enemy of Rome, Conan exists in an unknown time, when anything’s possible. All we’re told of his destiny is that last line, with its mythic, superhuman invocation of Earthly thrones trodden underfoot as though he were some avenging angel.

The story that follows begins with similar scenes to the Kull adventure, showing us first conspirators and then the king weary of kingship, but cuts the subplot about forbidden love; Conan, unlike Kull, is not wholly enervated by kingship, is not hedged round by custom. Being king is a challenge for him, it’s tiring, but we get the sense that this is really raising the question of whether his subjects are worthy of him. Now, at this point in the story Kull meets the young noble in love; but Conan instead marks out on a map the lands of his birth, in the largely unknown north. Again we get the sense of a man from beyond the known world: “By Mitra,” says his counsellor and friend, “I had almost believed those countries to be fabulous.” Even to one who knows him well, Conan’s homeland is a fable. More so once we find out the names of the places: Asgard and Vanaheim, lands of myth. Conan describes his home — “a gloomier land never was” — and links it with his gods: “Crom and his dark race, who rule over a sunless land of everlasting mist, which is the land of the dead.”

All told, there’s a strongly mythic feel that’s absent from the Kull story. Conan himself isn’t a myth, but the overtones and echoes have to do with myth in a more thorough way than is the case with Kull. We can see it as the story continues: the rebels turn out to be inspired by a sinister wizard, Thoth-Amon, giving the assassins a dimension beyond the would-be killers in the Kull tale. And where Kull was saved from his killers by happening to be awake when they burst into his room, Conan is given a prophetic dream, and the mystic sign of the phoenix appears on his sword; the dream wakes him to face the assassins, and perhaps more crucially confirms him as the rightful king: “I have marked you well, Conan of Cimmeria, and the stamp of mighty happenings and great deeds is upon you … Your destiny is one with Aquilonia. Gigantic happenings are forming in the web and the womb of Fate, and a blood-mad sorcerer shall not stand in the path of imperial destiny.”

All told, there’s a strongly mythic feel that’s absent from the Kull story. Conan himself isn’t a myth, but the overtones and echoes have to do with myth in a more thorough way than is the case with Kull. We can see it as the story continues: the rebels turn out to be inspired by a sinister wizard, Thoth-Amon, giving the assassins a dimension beyond the would-be killers in the Kull tale. And where Kull was saved from his killers by happening to be awake when they burst into his room, Conan is given a prophetic dream, and the mystic sign of the phoenix appears on his sword; the dream wakes him to face the assassins, and perhaps more crucially confirms him as the rightful king: “I have marked you well, Conan of Cimmeria, and the stamp of mighty happenings and great deeds is upon you … Your destiny is one with Aquilonia. Gigantic happenings are forming in the web and the womb of Fate, and a blood-mad sorcerer shall not stand in the path of imperial destiny.”

So where the climactic battle serves to reawaken Kull’s sense of his own potency, here it becomes the working-out of a prophesied greatness, the proof of Conan’s rightful station. Where the first Bran Mak Morn story emphasises Bran’s failure and death, here we’re given the sense of a yet more triumphant future awaiting Conan the king. Conan reaches above the realm of romance toward myth.

Nowhere, I think, do we see this more clearly than in the tremendous scene in the story “A Witch Shall Be Born” when Conan, like Christ, is crucified in the desert, and, like Prometheus, has vultures descend upon him. Christ triumphed by dying, ascending, and being reborn; Prometheus by enduring until rescued by Hercules. Conan waits till one of the tormenting vultures comes too close — and tears its neck out with his teeth. “Ferocious triumph surged through Conan’s numbed brain. Life beat strongly and savagely through his veins. He could still deal death; he still lived.”

Nowhere, I think, do we see this more clearly than in the tremendous scene in the story “A Witch Shall Be Born” when Conan, like Christ, is crucified in the desert, and, like Prometheus, has vultures descend upon him. Christ triumphed by dying, ascending, and being reborn; Prometheus by enduring until rescued by Hercules. Conan waits till one of the tormenting vultures comes too close — and tears its neck out with his teeth. “Ferocious triumph surged through Conan’s numbed brain. Life beat strongly and savagely through his veins. He could still deal death; he still lived.”

If Conan touches upon the condition of myth, it’s also true that both Bran and Kull are presented as remarkable figures, superhuman in their physical capacities and skill in fighting. But more than that, all these men have some transcendant characteristic beyond the physical; a charisma, a force of personality. They have more life than the other characters in their stories. It’s a tribute to Howard’s skill that he conveys this sense so powerfully and convincingly.

Their vitality is frequently described as a function of their barbarity. They’re in touch with some wellspring of savage power that civilised men have forgotten. But not every barbarian, nor even every barbarian chief, is described in the same terms. In fact, Howard didn’t believe that barbarism was a good thing; only that it was inevitable, a part of the human condition.

There’s one more of his barbarians I want to talk about here, not technically a hero and barely even a character, but there nonetheless. As part of the background to his Conan stories, Howard wrote a background of the Hyborian Age, an outline of history stretching from Kull’s Atlantis to the beginning of historical times. Mostly in this document Howard describes the rise and fall of nations. But there’s an extended stretch near the end, arguably the climax of the whole narrative, where Howard describes the life and actions of a Pict king called Gorm, who lived for over a hundred years and created “a vast Pictish empire, wild, rude, and barbaric”. But: “Conquest and the acquiring of wealth altered not the Pict; out of the ruins of the crushed civilization no new culture arose phoenix-like … Though he sat among the glittering ruins of shattered palaces and clad his hard body in the silks of vanquished kings, the Pict remained the eternal barbarian, ferocious, elemental, interested only in the naked primal principles of life, unchanging, unerring in his instincts which were all for war and plunder, and in which arts and the cultured progress of humanity had no place.”

There’s one more of his barbarians I want to talk about here, not technically a hero and barely even a character, but there nonetheless. As part of the background to his Conan stories, Howard wrote a background of the Hyborian Age, an outline of history stretching from Kull’s Atlantis to the beginning of historical times. Mostly in this document Howard describes the rise and fall of nations. But there’s an extended stretch near the end, arguably the climax of the whole narrative, where Howard describes the life and actions of a Pict king called Gorm, who lived for over a hundred years and created “a vast Pictish empire, wild, rude, and barbaric”. But: “Conquest and the acquiring of wealth altered not the Pict; out of the ruins of the crushed civilization no new culture arose phoenix-like … Though he sat among the glittering ruins of shattered palaces and clad his hard body in the silks of vanquished kings, the Pict remained the eternal barbarian, ferocious, elemental, interested only in the naked primal principles of life, unchanging, unerring in his instincts which were all for war and plunder, and in which arts and the cultured progress of humanity had no place.”

That’s the vanished greatness which Bran Mak Morn is fighting to restore. Now, like Bran, Kull and Conan are barbarians; and like Gorm, they are conquerors. But Kull is curiously ineffectual, while Conan receives mystical confirmation of his fitness to rule, of his destiny of greatness. Interestingly, that benediction comes through the image of the phoenix, while Gorm’s barbarity precludes any further culture arising “phoenix-like” from the old.

Gorm is a static creation, seen from a distance. Conan, Kull, and Bran are characters; and they’re different characters, occupying different stages on the continuum from tragedy, the high mimetic, up toward myth. The variety among those characters indicates the breadth of meaning that the barbarian hero had for Howard. And, by describing it as powerfully as he did, by illustrating the tension between an idea of civilisation and the idea of the barbaric, Howard made his concerns ours for at least as long as we choose to read him.

Any truly archetypal image can be analysed a number of ways. You can look at Howard’s barbarians as images of masculinity, of power, of rebellion, of identity, of any number of things. The point is that any one analysis won’t manage to grasp everything about them. For all the meanings you can tease out, you still feel there’s always something more left. The barbarians are in this sense irreducible; they are the most efficient explanation of themselves.

Any truly archetypal image can be analysed a number of ways. You can look at Howard’s barbarians as images of masculinity, of power, of rebellion, of identity, of any number of things. The point is that any one analysis won’t manage to grasp everything about them. For all the meanings you can tease out, you still feel there’s always something more left. The barbarians are in this sense irreducible; they are the most efficient explanation of themselves.

In the end, I think they all in different ways illustrate Howard wrestling at some level with the concept of barbarism; or, more precisely, with the archetype of the barbarian. I think the relations these men have to empire and to civilisation reflect different aspects of an image or idea that gripped Howard, and was key to how he saw the world and how he saw history and how he saw people. I think some clue to what makes Howard worth reading lies in his ability to get at that image, to describe it so powerfully. I think in essentially inventing sword and sorcery, he created the right form to dramatically embody the symbol of the barbarian.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

Great article!

One might consider Howard in the context of his post-WWI era. The “Great War” was known for its sheer barbarism–a savagery that was made worse by the advent of the Industrial Revolution. Killing technology (guns, gas, bombs, planes) had far outstripped healing technology (i.e. medicine), and Europe became a global meat-grinder for years, trapped in a struggle of seemingly endless slaughter. When the U.S. intervened the tables were turned and the greatest carnage the world had ever known was ended in one final year of horrendous trench warfare.

Those writers and poets and thinkers who lived in the wake of The Great War had admittedly lost faith in humankind, in human progress, perhaps in man’s ability to be more than savage and barbaric. While Howard isn’t usually considered part of the Lost Generation that included Hemingway and other mainstream writers, it does make some interesting food for thought. Where came Howard’s absolute fascination with barbarism and contempt for the masque of modern civilization? Considering the mood of the post-WWI intelligencia and creative communities, it really wasn’t that unique. WWI was a vast orgy of death, destruction, and murder. It was in many ways the antithesis of everything Civilisation should represent (i.e. logic, reason, compassion, learning, diplomacy, brotherhood).

So that struggle between the barbaric and the civilized that captivated and obsessed Howard (informing all his work) was a legitimate reaction to the confused state of existence that predominated Western thought in the years between WWI and WWII.

Is man a Savage or an Artist? The ironic truth is that he is both. Therein lies the crux of Howard’s art, with its fascination and exploration of the Savage against a backdrop of ancient civilizations. And here we are in the 21st Century, still facing that same struggle in our essential human nature. This is one reason Howard’s work remains so vital and engaging. Conan, Kull, and all their ilk…they speak of the core of humanity.

Great insight, Mr. Surridge and very observant comment, Mr. Fultz.

To go along with that comment, was the influence of Howard’s home in Crossplains, with its boomtown and economic crash cycle, inspiring his ponderings on the rise of civilization from barbarianism and then civilization tendency toward decay to br eventual being overrun by barbarianism again.

By no means am I trying to take credit for that observation. Of Couse I read it in others’ essays that were tucked away in various REH books, but it’s just one that I found relatable to the places I grew-up, so I found it all the more profound.

Thanks for the kind words, John and Greg!

I like both of the approaches you suggest to Howard. I’m a big believer in looking at writers in their context, especially historical context. I was thinking at one point in the article mentioning the pulps, and the idea of heroism and the specific pulp hero character that was emerging in the 20s (I’ve been working on something for a friend’s podcast about Golden Age superheroes), but in the end decided it didn’t really fit. I think looking at the issue of barbarism in relation to World War One is an even better link. Especially, I wonder now how much the civilisation of the Roaring 20s helped inspire the depiction of civilised decadence in Howard’s work.

And I know Howard very strongly thought of himself as a Texan writer, and felt himself to be shaped by his surroundings. There are some autobiographical writings, which I read in Glenn Lord’s The Last Celt, all about that sort of thing; going back into his family history, and so forth. I recall that he also once wrote that Conan was based on men he actually knew, roughnecks and boxers and so on. So certainly that’s directly out of his own experience …

Nice work Matthew, and a lot to think about here.

Props for working Northrop Frye into an article about Howard’s barbarians! I think Frye’s theory works with Conan, Kull, and Bran, and it certainly helps to make a case against those who claim that all Howard’s heroes were the same.

[…] This post was mentioned on Twitter by Stephen Gordon, Tor.com Fantasy. Tor.com Fantasy said: A great article on the Black Gate website about Robert E. Howard, Conan and Barbarians: http://bit.ly/g3Kdas […]

[…] writing here know that I like a lot of adventure fiction quite a bit. I’ve written enough about Robert E. Howard, early Marvel comics, Jack Vance’s Dying Earth — I’ve even written about Fighting Fantasy […]