How We Got Where We Are, or Go Adam West, Young Man

Gather round, kiddies, and I’ll tell you a story. Hey — are you listening? Turn off the TV (oh, excuse me, put away your device) and stop watching Agents of Shield, Supergirl, Daredevil, Gotham, Arrow, or The Flash, for just one minute! Hold on a second — don’t run out the door! This won’t take long, and I promise you won’t be late for the start of X-Men: Apocalypse, Deadpool, or Suicide Squad. Pay attention, and put away the deluxe slipcased fifty dollar hardcover editions of The Sandman or V for Vendetta or The Dark Knight Returns. I know, but you can finish your doctoral dissertation on Mimesis and Mutation: Gender Fluidity in the X-Men some other time! Please — close the browser; you can read later about how the two Avengers movies alone have taken in three billion dollars at the box office (not counting home video or merchandising money).

Three billion dollars. That’s two movies. Just Marvel movies. Out of over forty Marvel movies. Add in the take from the less aesthetically pleasing but still insanely profitable DC side of the street and the figure simply stops making sense. The number is more incomprehensibly mind boggling than Galactus showing up to eat the world, more wildly absurd than Bruce Banner being mutated into a huge green monster by gamma rays, more utterly improbable than a blue-blanketed baby escaping an exploding Krypton in a homemade rocket, and more sheerly ridiculous than a smoking-jacket wearing millionaire dilettante somehow getting the notion that bats strike fear and terror into the hearts of criminals. It’s just un-flippin’-believable.

As Randy Newman reminded us long ago, it’s money that matters, and in terms of cold hard cash, can there be any doubt that comic book superheroes are the engine that runs the movie and television industry, which means that comic book superheroes are the engine that runs American popular culture as a whole?

But here’s the thing — incredible as it may seem to anyone under the age of, say, forty, there was a time within living memory when comic books and everything connected with them were — are you sitting down? — the most contemptible and disposable of cultural artifacts; they were nothing but crap for kids.

When did that start to change? When did comic book creations start to move from under the bed and into the mainstream? I submit that the turning point was the January 12, 1966 premier on the ABC Network of the Batman television show, Starring Adam West as Batman and Burt Ward as Robin (the Boy Wonder), because it was the first time any costumed comic book crimefighters were successfully pitched at anyone over the age of twelve.

Batman’s closest analogue is probably the Adventures of Superman, which starred George Reeves as the Man of Steel and ran from 1952 until 1958, but that charming and energetic show, while much — and deservedly — beloved, was essentially for children; its sensibility was little different from that of bottom-rung juvenile fare like Captain Video or Rocky Jones, Space Ranger.

Batman, on the other hand, while fast-moving and colorful enough to appeal to young viewers, was primarily aimed at adults. The key idea here is “camp,” a term denoting “an aesthetic style and sensibility that regards something as appealing because of its bad taste and ironic value.” Camp was much in vogue during the sixties and seventies, and if you don’t hear the term much used any more, it’s for the same reason that no one makes excited remarks about encountering electric lights or indoor plumbing — its total triumph has rendered it almost invisible. There’s not much left in American culture today but camp.

The Big Three

One of the functions of camp is to take something essentially juvenile and imbue it with a flip, knowing dimension that only adults can appreciate (and that adults will be willing to pay for); in-joke humor is a fundamental part of its appeal. Thus, the 1966 Batman is purposely funny, unlike today’s dominant incarnation of Bruce Wayne and his alter-ego, the teeth-grindingly serious Frank Miller/Christopher Nolan version, which is so grim that the slightest acknowledgement of the ridiculousness of the setting, situation, or (especially) protagonist would instantly cause the whole enterprise to fall apart. (The Nolan Batman would be rendered helpless if just one person simply said, “Why the hell are you talking like that?”)

The fundamental absurdity of costumed crime fighters has always been at least implicitly acknowledged by many of the best comic creators, artists and writers like Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, C.C. Beck, Jack Cole, Steve Ditko, and especially by Will Eisner, paradoxically the creator of the most grown up comic book hero of them all, the Spirit. In an interview with Jim Steranko, Eisner acknowledged injecting a large amount of humor into the Spirit, because, “I never could understand why any crime-fighter would go out and fight crime. Why the hell a guy should run around with a mask and fight crime was beyond me.” If you accept the premise that costumed crimefighting is fundamentally ridiculous, there are two main ways to deal with that ridiculousness: ignore it or embrace it.

The Batman of the last several movies deals with the problem of inherent silliness by rigidly refusing to acknowledge it, in the increasingly mistaken belief that that will make it go away. The 1966 show chooses the opposite path; it makes silliness its flag and marches forward triumphantly under that banner (or at least it did until the ratings slipped and it was cancelled, a fate that may yet be in store for the current overheated, grim version).

Unashamed goofiness is apparent in every aspect of the show, and to catalog individual examples would be reductive; a few will have to suffice. In the midst of the fistfights that occur with clockwork regularity in every episode, garishly fonted, brightly colored classic comic book sound effects appear right on the screen: Bam! Pow! Zap! Boff! Crash! Zlott! (Zlott?). Those fights are always against dimwitted, cute-named, off-the-rack henchmen who are theme-dressed to go along with their leader villains (Catwoman’s henchmen wear cat ears and whiskers, King Tut’s stooges are dressed like Egyptian servants, etc.)

The Batcave

Everything connected with the crimefighters has the adjective “bat” attached to it, from the “Batusi” that Batman dances to the Bat Anti-Crime Computer in the Batcave to the Bat-Shark Repellant that Batman just happens to have in his utility belt and that saves his life during a dramatic surfing contest with the Joker, an incident that there’s really nothing more to say about, is there?

When Batman and Robin use the Batrope to climb the side of a building, they’re likely to be accosted by an “ordinary citizen” sticking his or her head out of a window, such ordinary citizens including Dick Clark, Colonel Klink (from Hogan’s Heroes, which I guess answers the question of whether Klink was acquitted at Nuremberg), Lurch (from The Addams Family), and Sammy Davis Jr. (Their first such encounter was with Jerry Lewis. If Batman and Robin were really concerned with making the world a better place, they would have hauled him in and let the Bookworm go.)

But the great, underlying joke of the show is the straightfaced, straightlaced, unwavering, in-every-way straightness of Batman and Robin and indeed, of every nonvillainous character in Gotham City. One wonders if there might have been a reaction here to the allegations of decadence and homosexuality made against the characters by Frederick Wertham in his incendiary 1954 book, Seduction of the Innocent. Just as the Miller/Nolan Batman would melt away like the Wicked Witch of the West under a bucket of water at the first hint of humorous self awareness, so the 1966 Batman would dissolve into shrieking nothingness should a male villain — say the Mad Hatter, Louie the Lilac, or Chandell, the evil pianist (played by Liberace, no less) make a pass at him.

This Batman will delay the hot pursuit of an escaping villain to lecture Robin about the necessity of always wearing a seatbelt. Before he punches a henchman, he reminds the malefactor to take off his glasses. He drinks only milk. He is truly, deeply shocked by the suggestion that any decent, hard working citizen of Gotham City might try to get out of paying his taxes and scolds Chief O’Hara for even suggesting such a thing.

This Robin won’t drive the Batmobile, even in a dire emergency, because he doesn’t have his driver’s license yet and who, when he goes undercover as a young delinquent, gives himself away when offered a cigarette — he coughs and sputters and has obviously never smoked anything in his life. Both he and Batman have an ironclad commitment to never let crimefighting interfere with homework. The pair are so straight they make Pat Boone look like Oscar Wilde.

From the perspective of fifty years later, does it still work? Yes, it does — it still comes off surprisingly well because of the total commitment that Adam West and Burt Ward have to playing these stiffs. They do not wink, blink, nudge, shrug, or roll their eyes — they look straight ahead and play these marionettes as if it were the most natural thing in the world, as within the confines of this all or nothing, unambiguous universe, it is.

Commissioner Gordon and Chief O’Hara

If the good guys are good (and mention has to be made of Alan Napier as Alfred, as adept at maintaining the atomic reactor as he is at dusting the Batphone, Neil Hamilton as the impeccably groomed Commissioner Gordon, and Stafford Repp as the bustling if ineffectual Chief O’Hara), then the bad guys are deliciously, extravagantly bad. The show’s big three are truly one — or three — of the glories of sixties television. Frank Gorshin as the Riddler, Burgess Meredith as the Penguin, and Cesar Romero (the Man Who Would Not Shave His Moustache, just put the white pancake on right over it, dammit, I’m not shaving it) as the Joker tear into their parts like a dog on one of those Alpo commercials where Ed McMahon shoves the bowl in front of the mutt and almost loses a finger because the famished hound goes for it so fast and you know, just know, that they haven’t fed the poor animal for twenty four hours at least so as to make sure the sponsor’s product looks real, real appetizing. Like that.

Never has villainy been so delightfully appealing, and why not? These villains always have pliable if dumb henchmen willing to follow their every command, a gorgeous ladyfriend (or “poor, deluded girl,” as Batman is wont to say) at their sides, an exotically decorated hideout (in an “abandoned warehouse on the outskirts of town” — Bruce Wayne could put an end to crime in Gotham City if he would just buy up and demolish all those abandoned warehouses), and a dynamite wardrobe. (As far as I’m concerned, for sartorial splendor there’s no “bat” anything that can match the Penguin’s monocle, cigarette holder, and lavender bow tie and top hat.) Add to that the fact that in Gotham City the maximum prison sentence is apparently about six weeks and there’s really no reason not to go into crime, Batman’s civics lectures notwithstanding.

The word apparently went out fast, far, and wide — on this show you can have a ball. No one will ever tell you to tone it down and the money’s good, too. Hams leaped off the shelves and hit the ground rolling — Vincent Price (Egghead), David Wayne (the Mad Hatter), Julie Newmar (Catwoman), Roddy McDowall (Bookworm), Shelly Winters (Ma Parker), Otto Preminger (Mr. Freeze), Cliff Robertson (Shame), Tallulah Bankhead (Black Widow), Art Carney (the Archer), Milton Berle (Louie the Lilac) — all strive to outdo each other in delirious excess.

Victor Buono as Tut

But even in such exalted company, one name shines above the rest. In his ten appearances as King Tut, Victor Buono takes hamminess and elevates it to a height it had never achieved before, and will never reach again. It is impossible to go any further; his line readings ooze and burble with all the curdled, frustrated artistry of a famed Shakespearian come down in the world. It’s as if Laurence Olivier were compelled to don bib overalls and appear on Hee-Haw. Watching Buono on Batman is almost more fun than the human nervous system can stand. It’s a hilarious, over the top characterization for the ages.

Beyond the performances, the show looks great — it was clearly a higher level production than The Adventures of Superman. Its Batmobile (which sold to a private collector for 4.2 million dollars a few years back) and Batcave have become truly iconic, and the show’s production design, its sets, costumes, and camerawork, its bright primary colors and tilted camera angles all make it visually ravishing, even after the passage of so many years.

Batman was unique in its day for its cliffhanger structure; during its first two seasons the show aired twice a week, the first half-hour episode ending with the Caped Crusaders in some villain-devised deadly peril (clinging to the wall over a pit of alligators, tied to the clapper of a huge bell, strapped into an electric chair, and always with time running out!), with the next night’s episode resolving the peril and wrapping the story up with the defeat of the villain. At the end of the first episode of the pair, the show’s narrator (producer William Dozier himself) would always breathlessly urge us to “Tune in tomorrow — same bat-time, same bat-channel!”

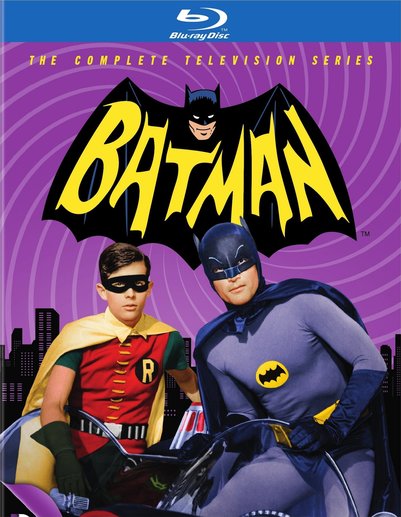

It’s still worth tuning in to today. Two years ago, after long being the despair of fans everywhere, who assumed that a tangle of money and rights disputes would prevent the show from ever appearing on home video, Batman was finally released on DVD and Blu-ray. It’s a little pricey (especially on Blu-ray) but it’s well worth it. Beyond the historic significance of making it ok for adults to watch the antics of such costumed characters without drawing the shades — a door that it opened and that has done nothing since but open wider — the 1966 Batman is just a lot of fun.

It’s a far cry from today’s iteration of the character, that’s for sure. It can’t be charged with lack of seriousness because seriousness was never its aim, and it can’t be charged with lack of realism for the same reason. The grim, dark, brutal, humorless Batman of recent years certainly sees itself as being deadly serious and many would claim for it a gritty realism too. The seriousness can be argued, but I would assert that the current Batman is just as unrealistic as the goofy, four-color Batman of Adam West ever was.

The two universes are both extreme and stylized, unrealistic in their own particular ways, which only makes sense, as their purposes are very different. Indeed, the 1966 Batman, with its ironic, knowing, camp sensibility, manages to avoid the main failing of the current screen Batman — sentimentality, which is simply an excessive, uncritical, self-indulgent regard for one’s own feelings and sensibility… and if that doesn’t describe the worst aspects of the Miller/Nolan Batman, I’m a bat-idiot. At the very least, the 1966 Batman is a highly enjoyable antidote to an overdose of the grimdarks.

So… if you’ve gotten all of your homework done, come plop down on the sofa with a tall glass of milk and travel back to 1966, where you can ponder how Bruce and Dick can jump onto the top of the Batpoles in stately Wayne Manor in their civilian clothes but reach the bottom in the Batcave a few seconds later in their costumes…some sort of automatic Bat-Haberdashery device, no doubt, and… wait — it’s the Batphone!

Just remember… be here tomorrow — same bat-time, same bat-channel!

Thomas Parker’s last article for us was Hope, Heroism, and Ideals Worth Fighting For: Darwyn Cooke, November 16, 1962 – May 14, 2016

Great Cesar’s ghost,

Of all the hours I spent watching “da Bats” forty-some years ago, there is only one scene that remains truly burned into my cortex: the ol’ “Bat Shark Repellant” ploy in the surf-off with the Joker!

Lol, did they even “show” the shark, or did that danger remain entirely off camera?

Many Thanks, -Anthony

Nice post! Best Batman, to this day. Though I don’t view this show as the trigger point between kid and adult targeting (commercially, anyways).

Alan Napier was Sherlock Holmes before he was the reliable Alfred.

This series is a classic of its kind, and – like you say – exposes the irony and humour deficit that typifies the recent batch of superhero movies. And maybe Burton’s Batman is a bridge between the two?

Victor Buono clearly had a lot of fun playing the criminal mastermind ‘Schubert’ in ‘The Man from Atlantis’. His delivery always reminded me of Vincent Price. Which makes me wonder: does being born in San Diego make you a southerner?

I wish you hadn’t mentioned “The Man from Atlantis,” Aonghus, I really do. Now I’m going to see the drowned face of Patrick Duffy floating before me all day…and I have a lot to do.

What?? You didn’t like ‘The Man from Atlantis’?

I always had a soft spot for this series (well, I haven’t seen it since it aired) maybe because Duffy is Irish-American (and looks like he grew up in Kerry) and one episode was directed by Michael O’Herlihy – younger brother of Dan, of ‘Robocop’ fame, and a bone fide Irishman.

No Aonghus, I too actually like “The Man from Atlantis.” It’s a surprisingly decent show; I often feature it on my Aquatic Television nights, along with Stingray, Voyage to the Bottom of the Sea – which may be my favorite show of all time (and I shudder to think of what that says about me), and Seaquest DSV, or as it was quickly dubbed by critics, “Voyage to the Bottom of the Ratings.”

It’s just that an opportunity to take a random swipe at Patrick Duffy doesn’t come along all that often, you know?

Victor Buono was quite a character. He was nominated for an Oscar for Whatever Happened to Baby Jane and he was a frequent guest on the Johnny Carson Tonight Show, where he would read his own poetry, which was side-splittingly funny. Anything he appeared on was worth watching.

How did I miss Tallulah Bankhead?

Every Batman after Tim Burton’s — and really, Burton’s own sequels — has disappointed me, precisely for the reasons you outline here. At least Burton’s first go at Batman gave us that Waltz to the Death fight scene in the belfrey, with its combat uses of church bells and its perfect score by Danny Elfman.

I grew up on the old Batman in syndication, and it has troubled me that my children have no idea why it’s funny when my husband and I engage in campy faux-fisticuffs while calling out, “Biff! Pow! Socko!” Glad to see the old episodes are available now.

I think I can shed light on Sarah’s last comment. When this show first aired in the UK, I would have been 9 or 10. TV was black & white, in those days, so the bright technicolor was not evident. But it was such a strange show, that me and my mates just loved it. Instead of true to life criminals despeate for money to get out of dead end jos, robbing banks and knocking out real policemen, we got criminals in costume living a life of crime with no thought of hardship. Then all the technology, the cliff hanger at the end of the first episode and the BAM! POW! at the end of the second. What’s not to like. But, but, but – we began to grow up a little. Discussions in the playground would start nitpicking. Why is the plot always the same? Why do they always manage to get out of the dilemma at the beginning of the 2nd episode? How do they manage to change into their costumes? This show is a measure of how I became a little older, little more mature and a little more sophisticated. After a few episodes, Batman sucked. It was rubbish. How could anyone like this stuff? Catching repeats on UK TV, as a much more mature person with thinning hair and growing waist, I love the show. Batman stopping Robin from dropping litter as they abseil down a skyscraper. Criminals agreeing to wear silly costumes. Bow Pam Splat all over the place. Batman soon bores the kids but is one of the great 60s shows for adults. Neil

It’s been a strange experience watching through these shows, which I haven’t seen for probably thirty five or forty years. Often, I know exactly what’s going to happen or be said – exactly three or four seconds in advance. It’s like being a character in a Philip K. Dick novel. In the very first pair of episodes, Jill St. John gains entry to the Batcave by flawlessly disguising herself as Robin (I know, I know). Batman discovers the ruse, and in trying to escape, Jill falls into the atomic reactor. Poof. Three seconds before Batman’s lips formed the words, I turned to the friend I was watching with and said, “Poor, deluded girl!” I still haven’t figured out whether this is making me feel very young or very old…

Oh man, my wife and I caught a few episodes of this a few months ago (Retro TV, I think). It was awesome! “We’re all gonna have a few drinks, overact, and then destroy the set.” What’s not to love!