Tarzan Swing-By: Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”

I would like to step forward at this moment to address the audience before the curtain rises on our feature book review presentation so that I may make a personal observation about Edgar Rice Burroughs. Specifically, I would like to explain why I’ve written so many posts about his work in the last few weeks.

I would like to step forward at this moment to address the audience before the curtain rises on our feature book review presentation so that I may make a personal observation about Edgar Rice Burroughs. Specifically, I would like to explain why I’ve written so many posts about his work in the last few weeks.

Burroughs needs no excuse for discussion in a magazine dedicated to heroic fantasy and planetary romance. Adventure literature as we know it springs from the influence of Burroughs in the early twentieth century. Although pulp magazines existed before Burroughs published Under the Moons of Mars (later titled A Princess of Mars) and Tarzan of the Apes, this double-punch in 1912 changed the style of this publishing medium for the remainder of its lifetime, and the influence continued into the paperback revolution and on into our era. Burroughs looms as one of the Titans of genre literature. But the true question is: Why am I re-reading so much of his work right now, in concentrated doses that I usually reserve for no author?

One answer is that I enjoy writing about Burroughs almost as much as I enjoy reading him. For an author who supposedly crafted straightforward entertainment, Edgar Rice Burroughs’s novels contain a remarkable breadth of ideas for debate and consideration. But a deeper reason for such current copious reading of Burroughs is that his work always gives me a unique uplift. In times of uncertainty and concern, I find that no author can temporarily re-energize me than ERB. Even a violent and embittered book, such as the one I’m about to discuss, provides an energy boost like a literary vodka with Red Bull. Burroughs knows how to make life seem wild, colorful, and far removed from the petty concerns of the everyday. It isn’t strictly “escapism,” a word I dislike, but a form of romantic empowerment. Burroughs’s daydreams on paper enhance our yearning for that which is beyond what we have to struggle with in day-to-day life.

End of psychological exegesis. The curtain now rises on today’s Tuesday Topic: one of Burroughs’s most unusual books, one that few people have read because — let’s face facts — how many but the most dedicated fans manage to reach Book #22 in any long-running series?

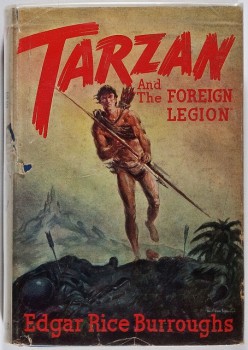

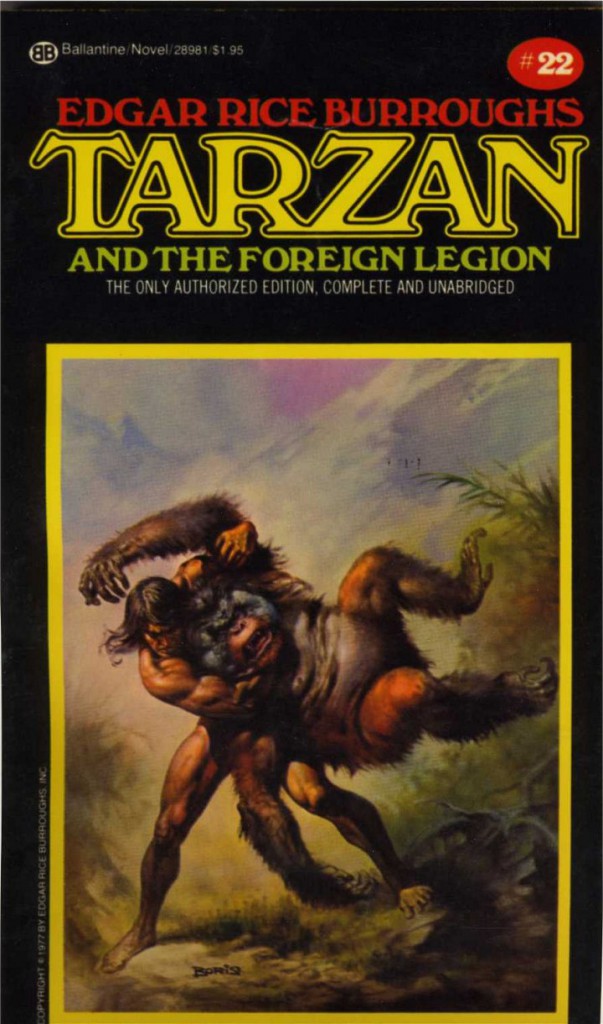

The Tarzan saga comes to its end with Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”. Although two more Tarzan books would appear posthumously, Tarzan and the Madman and the compilation Tarzan and the Castaways, Burroughs had written both previous to “The Foreign Legion.” He wrote this final Tarzan adventure in April–June 1944 in Honolulu during his service as a war correspondent. His own publishing company, Edgar Rice Burroughs Inc. (he was the first writer to incorporate himself), released the novel in 1947 with a cover from his son John Coleman Burroughs. It was the last Tarzan book published in the author’s lifetime. Only one more novel would appear before Burroughs’s death in 1950, Llana of Gathol, and that contained four previously published Barsoom novellas.

The Tarzan novels, which made their creator’s fame beginning with Tarzan of the Apes in 1912, limped through an interminable number of volumes and appeared creatively spent by the mid-1930s. The early Tarzan books contain some of Burroughs’s finest writing — the original is an uncontested American classic, and would make my short list of favorite novels — but the repetition among the last ten or so turns maddening. Only hardcore ERB completists can drag themselves through more than one of these late books consecutively. I found Tarzan and the Leopard Man almost impossible to complete, making it the only time I considered tossing aside a Burroughs novel unfinished.

But Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”, the twenty-second published Tarzan novel, shows Burroughs throwing off his formula for a last creative blast, and it’s one of the best entries in the long series. Apparently, Burroughs had also wearied of the continual parade of lost cities in the African jungles, Tarzan getting amnesia, Tarzan impostors, dueling vanished civilizations, and Jane under threat. Or perhaps the inspiration of war action convinced him to turn his writing toward a military adventure starring his most famous creation. Whatever the reason, the author pulled himself out of his slump for a strong final season.

Tarzan had gotten involved in world war before. In the seventh novel, Tarzan the Untamed (1919), set during the Great War, Tarzan fights German invaders who burned down his African estate and kidnapped Jane. The novel still depends on the standard jungle adventuring, only with bloodthirsty German villains as an opening sally, a move that got Burroughs in some serious trouble with his German readership during the 1920s. But Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion” puts Tarzan into a World War II movie and casts him alongside a motley bunch of American soldiers right out of Hollywood Central Casting — comic relief included. Trapped on the Japanese-occupied island of Sumatra, they form an ersatz “Foreign Legion” — hence the quotation marks in the title, so readers won’t expect Tarzan to go to Algeria to join the cast of Beau Geste. (John Clayton does speak fluent French, however. It might have worked.)

Tarzan had gotten involved in world war before. In the seventh novel, Tarzan the Untamed (1919), set during the Great War, Tarzan fights German invaders who burned down his African estate and kidnapped Jane. The novel still depends on the standard jungle adventuring, only with bloodthirsty German villains as an opening sally, a move that got Burroughs in some serious trouble with his German readership during the 1920s. But Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion” puts Tarzan into a World War II movie and casts him alongside a motley bunch of American soldiers right out of Hollywood Central Casting — comic relief included. Trapped on the Japanese-occupied island of Sumatra, they form an ersatz “Foreign Legion” — hence the quotation marks in the title, so readers won’t expect Tarzan to go to Algeria to join the cast of Beau Geste. (John Clayton does speak fluent French, however. It might have worked.)

The story opens brutally when a Dutch family flees the Japanese invasion of Sumatra. The parents both die, leaving their daughter Corrie van der Meer in hiding for two years. Eventually, the Japanese Captain Matsuo and Lieutenant Sokabe find her and carry her off as a prize.

The remainder of the set-up gets taken care of in the next chapter. An American Liberator plane, while on an unarmed reconnaissance mission, gets shot down over the Sumatran wilds. Four of the crew manage to bail out and land safely. British observer Col. John Clayton hits the ground and immediately strips to a loincloth and starts swinging through the trees, right at home in the jungle. It doesn’t take much for Clayton to revert to his true personality of Tarzan of the Apes. As Burroughs has reminded us many times, Clayton feels himself closer to Tarzan than British nobility.

But Tarzan is not alone this time: he’s ready to lead the rag-tag band of soldiers in their deadly exile in enemy territory. His three companions are Capt. Jerry Lucas of Oklahoma, Sgt. Tony “Shrimp” Rosetti from Chicago, and Sgt. Joe “Datbum” Bubonovitch, a Brooklynite with a flair for zoology and big words served with a thickly rendered accent. In the repartee between the group, readers can often catch echoes of service comedies and sometimes the interplay between Monk and Ham from the Doc Savage novels. However, most of the characterization probably derives from Burroughs’s own experience with meeting enlisted men during his time as a war correspondent. His phonetic rendering of Bubonovitch’s and Rosetti’s accents in prose tends toward the annoying, but this was standard way of rendering argot during the time. The humorous exchanges are sometimes witty and other times overplayed, but it’s definitely not Tarzan business-as-usual.

When Tarzan and his “Foreign Legion” learn about the kidnapped Dutch girl in the vicinity, they move immediately to save her. Tarzan executes a clever rescue, but the Japanese pursue the band. Jerry Lucas professes a strong dislike for Corrie — actually for any woman — which immediately means the two will fall for each other hard. We know the rules. A love triangle of sorts develops when the Dutch guerrilla fighter Tak van der Bos enters the action, but after a few chapters of doubt, the novel dismisses this conflict with a sentence. Jerry’s own stated “misogyny” and the constant dangers he and Corrie face put up much greater obstacles to their happiness than the love triangle detour. Another romance develops for the team’s other avowed “woman-hater,” Shrimp, when he starts to fall for the Eurasian beauty Sarina, who comes to Corrie’s aid when she least expects it. (This is one of the few moments where Burroughs reverses the expectations of how the Asian characters will act, an event that surprises even Corrie.)

The adventures of Tarzan and his companions on Sumatra puts them up against not only the Japanese occupiers, but also Sumatran collaborators, Dutch pirates, and nature’s own menaces. The heroes get separated, kidnapped, rescued, and reunited through a string of escapades. They eventually join Dutch guerrilla fighters to take the combat to the Japanese in some thrilling jungle warfare. The climax features a breathless ocean pursuit, sharks and submarines included.

But Burroughs doesn’t forget his hero’s connection to nature and the animal fantasy aspect of Tarzan’s legacy. Tarzan discovers he can communicate with the orangutans on the island as well as he can the apes of Africa. He gets in a classic “fight for supremacy” with one of the bulls of an orangutan tribe, Oju. Later, Tarzan has to face Oju again after the furious bull ape kidnaps Corrie.

Much of this sounds like a standard Tarzan actioner, but it doesn’t read that way. Tarzan serves as a superhero who gets people out of jams and uses his jungle-lore when needed, but his companions are the true protagonists. This shift toward the supporting cast gives readers an outside perspective on the famous hero that rarely appears in the other books. Tarzan vanishes for extended periods, and the war action stays with the hardy and good-naturedly bickering American soldiers and the resourceful Corrie.

The inclusion of these additional heroes allows the story to develop more character interaction, and even some philosophical discussions. In one section, the Foreign Legionnaires debate the nature of war—and what hatred does for and to a person in conflict. “Hatred” forms the most important theme of the novel, which the characters revisit many times between the action. Burroughs approaches the idea of hated in an ambivalent way. Sometimes characters speak about the way hate twists people, such as what it has done to change Corrie, but at other times hatred seems the only logical response. In a talk with Corrie, Jerry makes the point that “Tarzan says that it does no good to hate, and I know he’s right. But I do hate — not the poor dumb things that shoot at us and whom we shoot at, but those who are responsible for making wars.” And Corrie responds that she feels she does not hate enough: “You never saw your mother hounded to death and your father bayoneted … If you had and didn’t hate them you wouldn’t be fit to call yourself a man.” These moments add a layer of moral complexity to the novel that is rare in Burroughs later writing.

The inclusion of these additional heroes allows the story to develop more character interaction, and even some philosophical discussions. In one section, the Foreign Legionnaires debate the nature of war—and what hatred does for and to a person in conflict. “Hatred” forms the most important theme of the novel, which the characters revisit many times between the action. Burroughs approaches the idea of hated in an ambivalent way. Sometimes characters speak about the way hate twists people, such as what it has done to change Corrie, but at other times hatred seems the only logical response. In a talk with Corrie, Jerry makes the point that “Tarzan says that it does no good to hate, and I know he’s right. But I do hate — not the poor dumb things that shoot at us and whom we shoot at, but those who are responsible for making wars.” And Corrie responds that she feels she does not hate enough: “You never saw your mother hounded to death and your father bayoneted … If you had and didn’t hate them you wouldn’t be fit to call yourself a man.” These moments add a layer of moral complexity to the novel that is rare in Burroughs later writing.

One philosophy that Burroughs spends scant time on is patriotism. This will strike many as odd, considering that Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion” is a wartime adventure with American soldiers battling the Japanese. But Burroughs creates a world of chaos where the only true motivation that makes sense is hatred for the declared enemy. This is a social as well as physical jungle, and operates under the jungle’s law. The story makes the enemy clear, but it rarely waves the flag for freedom and democratic ideals. Is this an embittered Burroughs speaking? Or does the story merely have no place for this philosophy, choosing instead to highlight the individual’s struggle over the nation’s? “I don’t think any of us know what we are fighting for except to kill Japs, get the war over, and get home,” Jerry says during one interlude. “After we have done that, the goddam politicians will mess things all up again.”

But Burroughs’s cynicism about warfare doesn’t mean he treats the established enemy with any sensitivity. There’s no point in belaboring the way he describes the Japanese. It’s ugly and in synch with the “power of hate” theme. Burroughs wrote the book during the height of the war in the Pacific, so don’t expect an even-handed Letters from Iwo Jima treatment. In fact, expect the treatment of the enemy to get quite brutal, with the Japanese described as “monkeys” of low intelligence and undiluted savagery. (The exception is the character of Lt. Tada, who is vicious, but has an excellent, even witty grasp of colloquial English. I wish he appeared in more of the book, since he makes a multi-faceted villain.) Burroughs probably based a lot of the racial insults on what he had heard from the soldiers he knew during his time as a war reporter.

However, and this the pulp scholar and objective academic in me speaking, I find the xenophobia and racism on display one of the book’s fascinating aspects; while reprehensible, they shed light on World War II attitudes without the prism of modern sensibilities. No writer would approach this material in the same way today. However, O Casual Reader, you have been warned. Not that I imagine casual readers will pick up this novel, and pulp fans and Burroughs enthusiasts will know what to expect from the time period.

The most refreshing character in the story is Corrie, who proves herself a capable shot with a rifle and a skilled archer in her jungle adventures. It feels as if Burroughs is trying to create a semblance of a 1940s woman, far removed from the types he had once written at the start of his career. Corrie still gets kidnapped and seized a lot, however. Burroughs wasn’t ready to totally break his formula into pieces.

The author treats his famous hero in some unusual ways. The name “Tarzan” doesn’t even appear until a quarter of the way through the page count. Tarzan’s companions finally realize Colonel Clayton’s identity when they watch him wrestle and kill a tiger with his bare hands. Burroughs can’t resist a referential joke in this heroic moment:

…raising his face to the heavens, [he] voiced a horrid cry — the victory cry of the bull ape. Corrie was suddenly terrified of this man who had always seemed so civilized and cultured. Even the men were shocked.

Suddenly recognition lighted the eyes of Jerry Lucas. “John Clayton,” he said, “Lord Greystoke — Tarzan of the Apes!”

Shrimp’s jaw dropped. “Is dat Johnny Weismuller?” he demanded.

No Shrimp, this fellow can speak in complete English sentences.

There is another instance in the book where it appears that people know Tarzan from popular culture: they know who he is and about his previous adventures. Since Burroughs often wrote his stories from the perspective of a fictional version of himself, a reader might assume that the pseudo-Burroughs documents have made it to the rest of the world, and apparently made it into the movies.

In another intriguing detour late in the story, Tarzan suggests that he has achieved longevity, perhaps even immortality, from an African witch doctor. This explains how he has appeared as a young, virile man in adventures stretching back to before World War I. In another meta-reference, Jerry comments after hearing this: “I never gave a thought to your age, Colonel … but I remember now that my father said he read about you when he was a boy. And I was brought up on you. You influenced my life more than any one else.”

Tarzan further elaborates on his opinion of his possible immortality:

“Would you want to live forever?” asked van der Bos.

“Of course — if I never had to suffer the infirmities of old age”

“But all your friends would be gone.”

“One misses the old friends, but one constantly makes new ones. But really my chances of living forever are very slight. Any day, I may stop a bullet; or a tiger may get me, or a python. If I live to get back to my Africa, I may find a lion waiting for me, or a buffalo. Death has many tricks up his sleeve beside old age. One may outplay him for a while, but he always wins in the end.”

Two ideas come to mind when I read this passage. One is that Jane, Tarzan’s wife, receives no mention anywhere in this novel. Has she perhaps died, or aged beyond Tarzan’s young years and left him? (Burroughs mentioned her fewer and fewer times starting with Tarzan, Lord of the Jungle in 1927, with her dropping out entirely for whole stretches of the series.) The second is that Burroughs, nearing his seventieth birthday when he wrote the novel, knew his own mortality was approaching. The elegiac power of this section is surprising.

But readers can safely answer the debate about Tarzan’s immortality: yes, he will live forever. Heroic icons such as he can never truly die. It is rare for an author to create an enduring popular culture immortal: Arthur Conan Doyle with Sherlock Holmes, Bram Stoker with Dracula, Ian Fleming with 007. Burroughs achieved it with Tarzan. And this last adventure — a powerful surge of action, characterization, comedy, fury, hatred, and rumination — proves why Tarzan at the last towers as, truly, Tarzan the Invincible.

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Los Angeles. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

[…] out anyway because it had always served him before. (In a few of his final books, such as 1947’s Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion” and the posthumously published I Am a Barbarian, he shucked his standard plots with impressive […]

I read Foreign Legion one summer about thirty years ago (along with about sixteen other books in the series, accumulating over $4(!) in late fees because I insisted on reading them in the order listed, not in the order interlibrary loan sent them to me). I have three significant memories from it. One is Tarzan slaughtering his way down the Japanese chain of command as they’re fleeing through the jungle. Another is one of Tarzan’s companions attempting to chew raw meat. The big one, however, is that discussion of Tarzan’s age. It’s one of my favorite scenes in the entire series.

Ryan,

If I wanted to take in some of Burroughs, where would be a good start?

NewGuyDave

Dave, with ERB it’s really a good case to start at the very beginning, when he was filled with the most enthusiasm: the first three Mars novels (A Princess of Mars, Gods of Mars, Warlord of Mars, which form a continuous story) and Tarzan of the Apes. After that, I would follow with At the Earth’s Core and The Land That Time Forgot.

Ryan, can you comment on the Venus series? I’d always planned to read it after the John Carter series, but after thirty-five books in just a few years, I was ERBed out. Never did get back to it.

One thing that struck me about Tarzan. While it seems that we have many “classic monsters”, we have fewer “classic adventure heroes”. Tarzan would count as among the few.

For an attempt to list more:

http://monsterkidclassichorrorforum.yuku.com/reply/546947

[…] idea with no need to be moored in continuity. He did something similar with the final Tarzan novel, Tarzan and “The Foreign Legion”, where Tarzan has apparently become immortal and no longer seems to have any […]

[…] apparent supernatural longevity the Lord of the Jungle has obtained (Burroughs hinted at this in Tarzan and the “Foreign Legion”) and provides footnotes for numerous references to his earlier adventures. The movie series of the […]