“Worms of the Earth”: Bending the rules of swords and sorcery

“Worms of the earth, back into your holes and burrows! Ye foul the air and leave on the clean earth the slime of the serpents ye have become! Gonar was right—there are shapes too foul to use even against Rome!”

“Worms of the earth, back into your holes and burrows! Ye foul the air and leave on the clean earth the slime of the serpents ye have become! Gonar was right—there are shapes too foul to use even against Rome!”

–Robert E. Howard, “Worms of the Earth”

Robert E. Howard has received his fair share of criticism over the years, including the accusation that he wrote shallow, muscle-bound characters that cut their way out of every situation. Violence by strong, self-sufficient swordsmen is the end game for solving all problems in REH’s stories, his detractors argue, not wits or guile or diplomacy. For example, in his audio book survey of fantasy literature Rings, Swords, and Monsters, author Michael Drout declares Conan an uninteresting character who simply “smashes everything in his path.” L. Sprague De Camp, who penned the introductions to the famous (infamous?) Lancer Conan reprints of the 1960s and 70s, wrote that Howard’s heroes are “men of mighty thews, hot passions, and indomitable will, who easily dominate the stories through which they stride.” Howard wrote escape fiction, De Camp continued, wherein “all men are strong…” and “all problems simple.”

These generalizations lead casual readers to conclude that Howard considered violence to be the answer to all of life’s problems. They reduce Howard’s stories to brutish pulp escapism and denude them of subtlety or complexity. Sword and sorcery and its fans are painted with the same broad, clumsy brush by association. “Sword and sorcery novels and stories are tales of power for the powerless,” wrote Stephen King in his overview of horror and fantasy Danse Macabre (1981). “The fellow who is afraid of being rousted by those young punks who hang around his bus stop can go home at night and imagine himself wielding a sword, his pot belly miraculously gone.”

These criticisms aren’t entirely groundless. It’s rather easy to find examples of Howardian heroes hacking their way through a problem. Kull of Valusia butchering a horde of Serpent Men in an orgiastic, cathartic red fury in “The Shadow Kingdom” springs immediately to mind, for instance. Howard was in many ways bound by the conventions of the pulps in which he made his living as a writer. But there are an equal number of examples of Conan using his wits to extricate himself from situations when brute force won’t suffice, his reaver’s instinct restrained by sovereign responsibility. And of course, Howard penned many more characters than his famous Cimmerian.

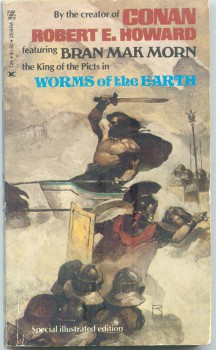

Howard’s 1932 story “Worms of the Earth” features the Pictish king Bran Mak Morn on an ill-advised mission to enlist supernatural aid to defeat an invading force of Romans. In it Howard substitutes complexity and compromise for crashing swordplay and victory in arms. While “Worms” is a tale of vengeance, it’s of a rather hollow, unfulfilling sort.

Bran has the appearance of a Howardian fantasy hero—wolfish, hard, steely-eyed, and possessed of a wild, savage strength—and the expectation is that he will cut himself free of any problems that arise. But in “Worms of the Earth” he’s confronted with the horrors of an ancient race beyond his physical capabilities. While he’s not a puppet on a string of said forces, Bran is no Nietzschean superman, either.

If the swords and sorcery genre is typified by the lone, strong hero acting on a singular mission, it doesn’t necessarily mean that there must always be a clear objective to conquer. Nor does every story need to reach a satisfying conclusion in which the hero rides off into the sunset, loot in hand and damsel laid across the pommel of his saddle. “Worms of the Earth” demonstrates the malleability of the swords and sorcery genre and in do doing reminds us of how great a writer Howard truly was. In addition to being well-written and atmospheric, featuring dark rides through spirit-haunted ancient Britain and a terrifying encounter with a Lovecraftian menace from under the earth, part of its appeal is in watching Howard turn heroic expectations firmly on their ear.

Here’s a bullet list of the surprising elements in “Worms” that put the sword to the lie of the perceived shortcomings of the genre:

• Fear. Bran experiences some serious misgivings—heck, skin crawling horror—when he descends into the dark pits of the worms of the earth. Not all swords and sorcery heroes are immune to the icy grip of fear.

• Boundaries. For all his hatred of the Romans, Bran realizes there are limitations to revenge and taboos one shouldn’t break.

• Compromise. Bran desires revenge but realizes he cannot accomplish it without outside agency. To find the worms he has to lower himself to intercourse with the (semi) loathsome witch-woman Atla. “The sex isn’t just sex; it’s transgressive sex; Howard’s hero demeans himself en route to damning himself,” wrote the late, great Steve Tompkins of The Cimmerian blog in a fine essay on the subject, “The Conscience, and the Kisses, of a King.”

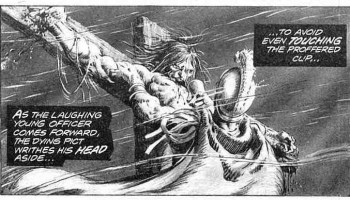

• Inaction. “Worms” starts off with Bran, operating under the name Partha Mac Othna, forced to watch the crucifixion of a fellow Pict. Although the man pleads with his eyes and expects succor from Bran, the king cannot act to save the doomed man’s life. The frustrating scene sets the tone for the rest of the story. In fact “Worms” features almost no swordplay—Bran only draws his blade twice to kill, and neither of his opponents raises arms in resistance. One slaying is purely an act of mercy.

• Inaction. “Worms” starts off with Bran, operating under the name Partha Mac Othna, forced to watch the crucifixion of a fellow Pict. Although the man pleads with his eyes and expects succor from Bran, the king cannot act to save the doomed man’s life. The frustrating scene sets the tone for the rest of the story. In fact “Worms” features almost no swordplay—Bran only draws his blade twice to kill, and neither of his opponents raises arms in resistance. One slaying is purely an act of mercy.

• Doubt. Bran is a proud member of the Pictish people and treats the Romans with the disdain due any invading force. But the existence of the race of “worms” casts doubt in Bran’s mind as to who truly holds ancestral rights to Britain. “Yet his race likewise had been invaders, and there was an older race than his,” Howard writes.

• Remorse. Bran exhibits pity, even for his worst enemy the Romans. His last act leaves his thirst for vengeance unslaked. “’I had thought to give this stroke in vengeance,’” he said somberly. “’I give it in mercy—Vale Caesar!’”

“Worms of the Earth” proves that the author who birthed swords and sorcery did more with the genre than most of his successors, and was already bending its “rules” even as he drew it, white-hot and smoking, from the blacksmith’s forge.

Very well written indeed. This is one of my favorite REH stories, and you’ve explained better than I could why it’s so strong. Bran Mak Morn, the last pure king of a degenerate and dying race, comes to face both those who came before and those who will follow. Rather than plowing through his enemies in a storm of blood, Bran ends the story seeing just how fruitless his struggles are, and yet how terrible the price he pays is. It’s an unnerving and powerful story. I particularly like your final metaphor about bending the rules even as he forged genre–because truly, sword and sorcery must have been forged from fire and steel!

[…] Black Gate Tags: “Worms, Bending, Earth”, Rules, sorcery, swords […]

I love that story! I think it might be the first fantasy/horror crossover, in as much as we define the modern genre.

Wow — very nicely said. Well done.

Great article. REH is my favorite author and Bran Mak Morn is one of my favorite of his characters, probably would be my very favorite if REH could’ve given us more tales about Bran Mak Morn.

“Worms” is a perfect example for the arguement.

And besides; even if critics of REH were right (but you proved them wrong here), I kinda still like the bad-@$$ who just kicks the crap outta his enemies.. Come to think of it, maybe these said critics just need a good @$$-whupin’.. LOL 🙂

None of REH characters are about just kicking a**. I’ve never read any bran mak morn stories but i’ve read a good number of conan ones. those are not all about a big guy with a sword if you spend time to look at them.

But how can ANYONE say Kull is all about fighting. Kull is a thinking man’s hero in my opinion. I bought the Del rey Kull stories thinking i was getting a conan clone. not even close. Even though i just read them for the first time last year those Kull stories have a special place in my heart.

I liked this article! And I’ve never even read Howard, being not at all drawn to the Cimmerian. But I might read “Worms of the Earth” just because of this. Thanks!

Thanks for the very kind comments, everyone.

Kid_Greg: I like a little ass-whupping in my fiction too, and Howard provides that in spades. I’d be lying if I said that wasn’t part of his appeal. I would bet it strongly appealed to Howard as well. He took out a lot of his real-life aggression in the boxing ring, and left us with stories that satisfy the same urges. But many of his stories run much deeper, including “Worms.”

Glenn: I agree, any critic who calls Howard shallow should be savagely beaten about the head and shoulders with a copy of “The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune.”

Totally awesome article Brian, thank you very much!

Drout’s claim that Conan is “an uninteresting character who simply ‘smashes everything in his path'” is insane! And while King’s word picture of a S&S reader can certainly ring true, his words that “Sword and sorcery novels and stories are tales of power for the powerless” pisses me off.

Love the analysis Brian. I look forward to the next one.

The critics of REH would prefer a Conan that, instead of fighting and overcoming his enemies, went on The View and cried.

Y’know, I’m not sure that King meant that literally, or rather not in a way that he is calling S&S fans wimps.

I kinda think he meant “powerless” to mean all of us in general. As in the context that in S&S we can take a sword to any unjust ruler or dishonorable foe, where as in real life, we’re more-or-less kinda powerless individually.

Say like myself for example, I’m basically another ant in the corporate cubical farm. If my boss is a jerk, and I want to keep my job,let alone keep from being arrested for assault, I’m more or less powerless to do much about it. But in a S&S yearn, (or many other genre fiction) I could tell him to draw steel and have at it.

Honestly, if you take King’s statement in that context, it rings true. I mean, that’s why I love S&S (as well as Westerns, etc..) In S&S, you can escape to a world, where a man of courage can strive and never has to take crap from anyone.

Then again, maybe King did mean it literally. ( I thought about it again after re-reading the post.) The whole crack about scared of the guys at the bus stop and the pot-belly thing.

But I guess to a certain extend, there is a sense of “powerlessness” in today’s socity for a lot of us, or just general muntaness.

So speaking for myself, its the adventurous escapism of S&S, that draws me; a world where honor and courage can be all a man needs for success.

Kid_Greg, I agree, I think escapism is one of the appeals of reading fantasy literature. And when we “return” to this world, it’s often with a sharper, clearer vision of how the world should work.

[…] una edición integral coloreada. Más imágenes e información en estos enlaces: [1] [2] [3] […]