Interview With James Stoddard: To Tour Evenmere, The Night Land, and Other Exotic Locales

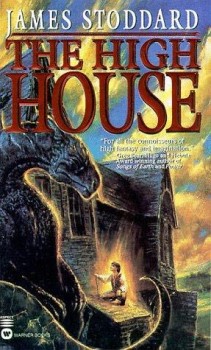

James Stoddard made his first short-story sale to Amazing Stories in 1985, under the pen name James Turpin. His first novel, The High House, published by Warner New Aspect in 1998, made an impressive debut. Publishers Weekly enthused, “In his first novel, Stoddard tells a thrilling story that features not only a unique and powerful family but a magnificent edifice filled with mysterious doors and passageways that link kingdoms and unite the universe.”

James Stoddard made his first short-story sale to Amazing Stories in 1985, under the pen name James Turpin. His first novel, The High House, published by Warner New Aspect in 1998, made an impressive debut. Publishers Weekly enthused, “In his first novel, Stoddard tells a thrilling story that features not only a unique and powerful family but a magnificent edifice filled with mysterious doors and passageways that link kingdoms and unite the universe.”

Cynthia Ward concurred:

“The modern armies of Tolkien clones have vanquished the diversity of high fantasy, with few exceptions: Little, Big by John Crowley, The Golden Compass by Philip Pullman, Clouds End by Sean Stewart — and now The High House, an astonishingly imaginative, individual, and assured first novel by James Stoddard.”

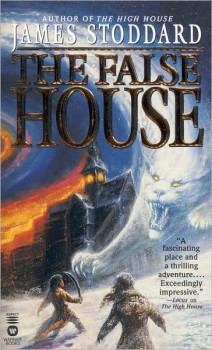

What would prove to be the first book in the Evenmere Chronicles was followed up two years later by The False House. And then the House went dark.

Loyal fans waited years — 15 years, to be exact. But on December 9, 2015, Stoddard fulfilled their wishes without help of a major publisher, releasing Book 3: Evenmere (Ransom House, available through Amazon for $12.89) and completing the story of Carter Anderson and the strange house that goes on forever, the house with a dragon in its attic and monsters in its basement and countless wonders in between.

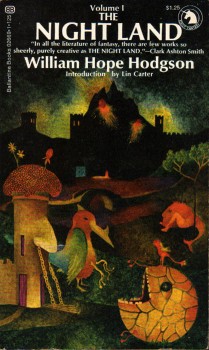

In the decade-and-a-half between visits to the High House, Stoddard also took readers on a tour of William Hope Hodgson’s strange future nightmare vision in The Night Land, A Story Retold (2010). He also returned to shorter forms, producing highly-regarded short stories and novellas for magazines like Fantasy & Science Fiction.

This past weekend I sat down with Stoddard (well, I presume we were both sitting when we sent these questions and answers back and forth via an esoteric form of magic that allows one to transfer messages instantaneously thousands of miles on invisible waves of electromagnetic radiation!).

Oz: The High House was an acclaimed debut that got some good critical buzz, winning the Compton Crook Award for best first novel. Although I’m sure I wasn’t the only one who looked forward to a sequel, The False House seemed not to have garnered the notice of its predecessor. You’ve said that while you always intended to write a trilogy, the publisher dropped the series after disappointing sales of the second book. How big was the drop from the first to the second novel, and do you have any theories of why that happened?

JS: I may have misspoken when I said the sales of the second book were disappointing. I’m really not sure if it was the second book or the overall series. I think both my agent and editor were expecting The High House to hit sales comparable to books like the Redwall series. Warner spent extra money on their release, using prestigious artist Bob Eggleton on the covers and adding raised, foil lettering, paying for some advertising, etc. They certainly made an effort, but sales were in the midlist range. I did feel that because of contractual deadlines, The False House wasn’t quite as strong as it could have been, which is why I did an extensive rewrite of it before releasing the new edition.

JS: I may have misspoken when I said the sales of the second book were disappointing. I’m really not sure if it was the second book or the overall series. I think both my agent and editor were expecting The High House to hit sales comparable to books like the Redwall series. Warner spent extra money on their release, using prestigious artist Bob Eggleton on the covers and adding raised, foil lettering, paying for some advertising, etc. They certainly made an effort, but sales were in the midlist range. I did feel that because of contractual deadlines, The False House wasn’t quite as strong as it could have been, which is why I did an extensive rewrite of it before releasing the new edition.

I’ve speculated on the reasons, but it’s just speculation. I like to think that if I had written the book in the ’80s, it would have made more of a splash, since it harkens back to older works. But the truth is that there are some terrific books, such as Joy Chant’s Red Moon and Black Mountain that simply fail to reach a larger audience. I’m re-reading her novel for the third or fourth time right now, and it’s a shame that a masterpiece like that has been out-of-print since 1974.

Oz: In the ensuing years, you have had notable success with some highly regarded short stories and novellas that have been published in the Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction and anthologized in annual Best Of collections. But what else have you been doing during this time? You have pursued a career in music recording? Tell us about that, or anything else you’ve been up to.

JS: That requires a bit of history. I’ve always been torn between two passions: writing and music. When I was in my twenties, I realized I had to decide which I wanted to pursue — there just wasn’t enough time to do both. So, even though I had gotten a short story published in Amazing Stories Magazine I stopped writing for over a decade. While working a day job as a Business Manager for a small school system, I earned a degree as a Sound Engineer at nearby South Plains College in Levelland, Texas, and built a home recording studio to record my songs. South Plains was the first college in Texas to offer such a degree, and I was fortunate to live thirty miles away.

JS: That requires a bit of history. I’ve always been torn between two passions: writing and music. When I was in my twenties, I realized I had to decide which I wanted to pursue — there just wasn’t enough time to do both. So, even though I had gotten a short story published in Amazing Stories Magazine I stopped writing for over a decade. While working a day job as a Business Manager for a small school system, I earned a degree as a Sound Engineer at nearby South Plains College in Levelland, Texas, and built a home recording studio to record my songs. South Plains was the first college in Texas to offer such a degree, and I was fortunate to live thirty miles away.

In that day the songwriting business really required a person to move to one of the major music centers in order to network with other songwriters, and though I spent a lot of time sending songs out and making occasional trips to Los Angeles, I never placed any songs. (There is also the possibility that I’m not that good a songwriter, but if so, I prefer to live in denial.)

I have no regrets about that, because it eventually led to my being offered a job teaching Sound Engineering at the college, which proved to be a great career. I loved teaching college students, and I loved the terrific, talented instructors I got to work with. I did that until last year, when I felt the time was right to go into writing full-time.

The High House and The False House were written when I was teaching. After the series was cancelled, I tried doing a couple proposals: writing a plot outline and the first two or three chapters of a proposed novel — they weren’t very good — I’m one of those who needs to write the whole novel. I also pitched my Night Land rewrite to my editor at Warner, but as you can imagine, the idea of selling a rewrite of a public domain novel doesn’t fit well with corporate publishing.

I wrote a hundred thousand word first draft of an undersea novel, which I may finish some day. John O’Neill was interested in publishing it in Black Gate as a serial at one point, until the print edition of the magazine was canceled. I spent five years writing a literary novel based on my childhood before setting it on a shelf — the problem with writing about your own life is that it’s hard to know what would be truly interesting to someone else — it’s all interesting when it’s about oneself. I have a novel I’m currently shopping. Its mythology is based on my short story “The Battle of York.” It’s an unusual concept, so we’ll see what happens. I like unusual concepts.

Oz: So you did complete that one long project during the “hiatus” — an overhaul of William Hope Hodgson’s magnificent (but flawed and somewhat inaccessible) work The Night Land (1912). I confess that while I was reading Hodgson’s The Boats of the Glen Carrig (1907) I experienced something I never have before or since: I wanted to rewrite it. Sure, when I was younger I daydreamed of writing sequels to some of my favorite books, and fan-fiction is a common enough hobby. But to read a book and think, “Oh, this is so good — but god it needs to be FIXED!” I wanted to add dialogue, mainly, and smooth some of the rough edges of his often awkward pseudo-archaic English. You actually went and did it with The Night Land — in addition to some excisions and other revisions. What motivated you to pursue such an undertaking? Did you feel like the “collaboration” worked out the way you’d hoped?

JS: As you can tell from the above, I have to smile at the word “hiatus,” which only happened when I was in my twenties. Gene Wolfe points out that the advantage of not writing full-time is that you’re able to write what you want without financial pressure. From an economic viewpoint, rewriting The Night Land was sheer insanity. I knew it at the time. I also knew that despite the flawed, stilted language the book is an absolute masterpiece that should not be forgotten. When doing the edits for the audio book, I recently re-listened to my version. To this day, whether I’m reading my rewrite or Hodgson’s original, I choke up during the last chapters.

JS: As you can tell from the above, I have to smile at the word “hiatus,” which only happened when I was in my twenties. Gene Wolfe points out that the advantage of not writing full-time is that you’re able to write what you want without financial pressure. From an economic viewpoint, rewriting The Night Land was sheer insanity. I knew it at the time. I also knew that despite the flawed, stilted language the book is an absolute masterpiece that should not be forgotten. When doing the edits for the audio book, I recently re-listened to my version. To this day, whether I’m reading my rewrite or Hodgson’s original, I choke up during the last chapters.

Calling it a “collaboration” is a good way to put it, because I was determined to maintain Hodgson’s vision throughout. Every chapter was a challenge at some level, whether it was adding dialogue, showing motivation, or dealing with mechanics. For example, in chapter 2, the hero is gazing out from the pyramid into the Night Land, describing what he sees. Hodgson described the view in one direction, then moved across to the opposite side. I thought it made more sense for him to describe the Night Land as he moved in a circle.

I’m very proud of how the book turned out, although I know that a certain sense of awe may have been lost with the change in the language. I think that if any of my books survive the decades, it might be this one, and I’m okay if I never make much money from it. (Though if it achieved the kind of recognition Hodgson’s genius deserves, that would be nice, too.)

Oz: After nearly two decades, you decided to write the third book, Evenmere, publisher or not. What made you decide to go ahead and finish it and put it out on your own?

JS: I kept getting emails from people, eight years or more after the book was out-of-print, asking for a third book. Gene Wolfe talks about the “Book of Gold.” Most readers have one or two books that are “the” book, the novel or novels that speak to their soul, that inspire, that they look to when they’re in hard circumstances. The Lord of the Rings is one of those books for me. I began to realize that the Evenmere books were that Book of Gold for some people. I got an email last year from a man from France, who wrote that he wouldn’t be the person he is today if not for my books. Writers live for those kind of letters. It’s gratifying and it’s humbling. I had actually almost completed a rough draft of the third book when the series was cancelled, so I felt I owed those readers, who had been so loyal and encouraging, another book. Again, it may not have been the best economic decision; I don’t know. But I was overjoyed when I learned my former editor at Warner, Betsy Mitchell, had gone freelance, so I was able to hire her to edit the book. To have her guidance on all three books felt so right and definitely improved the story.

Oz: Independent and self-publishing have become a viable option these days like never before — I see a parallel with independent musical artists and how they no longer need a record label to get their music out, thanks to the Internet. What are the advantages you see of writers going this route, and what are the disadvantages?

JS: Publishing with a major publisher is an exhilarating experience. You have the backing of a publishing machine behind you; your editor, assistant editor, and agent encourage you. You get distribution. Readers know that your book has been through a quality process. It gives you credibility. I would never have self-pubbed the three Evenmere books if the first two hadn’t been first released with a traditional publisher. Nor would I have released the third one without using a good editor.

JS: Publishing with a major publisher is an exhilarating experience. You have the backing of a publishing machine behind you; your editor, assistant editor, and agent encourage you. You get distribution. Readers know that your book has been through a quality process. It gives you credibility. I would never have self-pubbed the three Evenmere books if the first two hadn’t been first released with a traditional publisher. Nor would I have released the third one without using a good editor.

I’ve seen some self-published novels that were just horrible — incorrect grammar and comma usage, terrible sentence structure, awful dialogue. How do you know your writing is quality, if it hasn’t been recognized as such by anyone? And amid the thousands of self-published books, how are you going to market your work and make it stand out? I know there have been success stories with self-publication, but those aren’t the norm. If a person loves to blog and do marketing, self-publication might be a viable path. Some writers have a gift for that. But most of us don’t.

There is a perception these days that would-be novelists are supposed to write a novel and throw it up on Amazon. I don’t think it’s a useful path. I would advise instead to learn to write short stories good enough to get them published in major SF magazines. A lot of people say they want to be full-time writers, but refuse to write shorts, which is understandable, because a lot of us came to this business because we like reading novels. But if you want to be a professional, short stories are a way to hone your craft so you’re not making the same mistakes over and over through a 100,000-word novel. The short story I sold to Amazing Stories opened a lot of doors for me when I tried to sell The High House. It proves that some editor somewhere thought you were good enough to write professionally.

I tend to dismiss some of the things people call advantages about self-publication, such as having complete control. That can be useful for cover design, I think, but working with good editors makes for good books. For me, the biggest advantage is in bringing books back into print, or for unusual projects major publishers won’t take, such as my Night Land book.

Oz: The Evenmere Chronicles is now a finished trilogy, but do you think you might return to Evenmere and the adventures of Carter Anderson again?

JS: Not any time soon, I don’t think. I believe the three books stand together nicely, and I have some other swell ideas I want to pursue for awhile. But I seem to have hit on something when I wrote about an infinite house — several people have told me they often dream of wandering through vast houses. I still occasionally have the reoccurring dream that made me write the book, of traveling through secret passages. In some ways a house is an analogy for our soul, though I never thought of that when I wrote The High House. I don’t always know what my books are about until someone else tells me. So I may return to Evenmere someday. There are certainly an endless number of stories that could be told there.

Oz: You have written about the fantasy works that had a big influence on you, and you make many veiled homages to them throughout the Evenmere series. Leiber, Peake, Joy Chant, and many others — most of those were works reprinted in Ballantine’s Adult Fantasy series in the ‘70s. What are the more recent writers and works that loom large on your reading landscape now? Anything in the genres you’re following with particular interest in film or television or other media?

JS: My wife teases that I’ve nearly caught up to the 1920s in my reading. Despite having quit my day job, I still record music, so between that and writing I have very little time to watch television. Most SF movies aren’t really very good; The Martian was very well done, I thought, and Inception was an amazing film. Interstellar was also quite good. I’m a sucker for the super-hero flicks.

JS: My wife teases that I’ve nearly caught up to the 1920s in my reading. Despite having quit my day job, I still record music, so between that and writing I have very little time to watch television. Most SF movies aren’t really very good; The Martian was very well done, I thought, and Inception was an amazing film. Interstellar was also quite good. I’m a sucker for the super-hero flicks.

Sadly, as far as books, the Golden Age really is when you’re in your teens, and one begins to see a lot of the tropes repeated in newer works as time passes. I read the first book of The Hunger Games and thought it deserved every accolade it received. Right now I’m reading a formerly small press book, now self-pubbed from a local author, The King of Silk by Joe Douglas Trent, that shows promise. Fan and friend Jim Beard has co-written a fun pulp-style book called Airship Hunters. Black Gate should review that one if they haven’t already. Although I love Fantasy and SF, as a writer I have to force myself to read other things — if all I read is SF I can’t recharge my creativity. I’ve currently vowed to get a Classic Education by reading the Harvard Great Books series, so I’m struggling through that. Readers, not writers, are the best people to ask about great new books.

Oz: Related to that last question, one thing that is striking to me is that back when we were young and reading books like those anthology series edited by Lin Carter, the genre was still something of a “niche.” Now it permeates our culture. The people who don’t ingest fantasy through their reading, their movie-watching, or their video games are now very much in the minority. Any thoughts on this trend? Is it something to celebrate, or is there something to worry about?

JS: Well, our current presidential primaries are something to worry about. Apart from that I thought it was great when special effects reached the point where fantasy movies could be done well. There will come a time, I suspect, when the public grows tired of fantasy because there’s so much of it in the media. That may certainly affect SF as a genre. My larger concerns are that with the multiplicity of voices vying for our attention these days, it becomes increasingly easier for us to give ourselves wholly to entertainment and fantasy. We live in a country founded by educated, well-informed men and women of high ideals and integrity. We need to expect that for ourselves if we want to remain free.

JS: Well, our current presidential primaries are something to worry about. Apart from that I thought it was great when special effects reached the point where fantasy movies could be done well. There will come a time, I suspect, when the public grows tired of fantasy because there’s so much of it in the media. That may certainly affect SF as a genre. My larger concerns are that with the multiplicity of voices vying for our attention these days, it becomes increasingly easier for us to give ourselves wholly to entertainment and fantasy. We live in a country founded by educated, well-informed men and women of high ideals and integrity. We need to expect that for ourselves if we want to remain free.

Third Evenmere novel?!?!? [rushes off to Amazon]

Holy crud! I’m rushing out the door after Joe! I loved those books!

Joe H and Howard Andrew Jones:

I know, right? I ordered it as soon as I saw it was out.

[…] last week I discovered from an interview Nick Ozment held with the talented James Stoddard that there’s a third Evenmere book. I […]