A Bout of Aboutness: Urban Fantasy and Sword-and-Planet

The Zeitgeist has been tying its ectoplasm in knots lately about urban fantasy. Here’s Lilith Saintcrow, underdefining the genre in a recent guest column at Pat’s Hotlist (with a followup at her own site):

Chicks kicking ass. Well, leather-clad chicks kicking ass. Leather-clad chicks kicking ass in an urban environment where some form of “magic” is part of the world. There. That’s about it.

But that’s not all there is to it.

Certainly not, but that really may be the central genre-defining element. I was thinking about this while reading Justina Robson’s excellent Keeping It Real recently. The book kept reminding me of sword-and-planet–with the gender polarities reversed.

Certainly not, but that really may be the central genre-defining element. I was thinking about this while reading Justina Robson’s excellent Keeping It Real recently. The book kept reminding me of sword-and-planet–with the gender polarities reversed.

I was reading buckets of sword-and-planet last year (some of which I reviewed in this space) and it constantly occurred to me that the aboutness of these books is concerned with male identity: they present idealized images of the lone male adventurer. For Edgar Rice Burroughs, the idealized image was that of an immortal Virginia gentleman. For Robert E. Howard, a man somewhere midway between the barbarism he considered man’s natural state and the aspirations of human intellect. For Otis Adelbert Kline, he’s a down-on-his-luck member of the American aristocracy. For some other three-initialled author the idealized image might be somewhat different, but they share some core similarities.

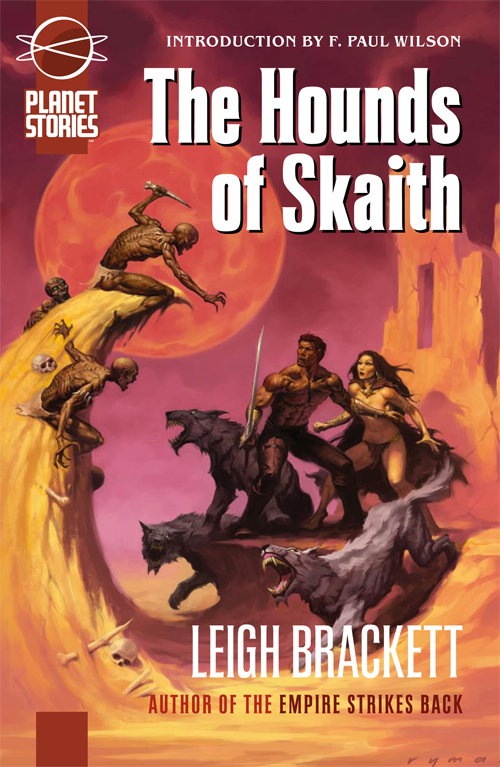

This concentration on masculine adventure doesn’t, I think, mark sword-and-planet as a male-only genre. Women share a world with men, and are at least potentially interested in what they are up to (in reality and in imagination) and, of course, they may just like the adventure. It’s a fact, anyway, that some of the greatest sword-and-planet stories were written by a woman, Leigh Brackett. Her worlds, her characters, her stories are all more various than the genre norm, but the hero (or antihero) is almost invariably a man: she doesn’t write usually write about Jirel-in-space–although sometimes she does (e.g. “Black Amazon of Mars” novelized as People of the Talisman), and the results tend to be interesting.

Urban fantasy is strikingly parallel to sword-and-planet in that it plunges a sole woman into a world of exotic adventure, and its aboutness seems to be concerned with female identity. The concentration on one central figure is key to the similarity: in a recent fascinating discussion of urban fantasy, Carrie Vaughn complained that many of these books fail the Bechdel test. I’m not saying that’s not a problem, but it may tend happen because of the genre’s aboutness: ideals do not travel in herds. (On the other hand, in S&P and lots of genre fiction, men talk to men about subjects other than women–what we might call the anti-Bechdel test–so this is at best a partial explanation.)

After defining the genre and talking about some problems she sees with particular examples, CV goes on enrich her c.v. (as it were) with a brief analysis of the causes of urban fantasy, the social need it addresses. CV argues that “these books are symptomatic of an anxiety about women and power.” I think there’s something to this, but I think there may be more, and the aboutness of sword-and-planet (I almost wrote sword and plant) plays a role in my thinking.

There are lots of causes for the outburst of genre fiction in the first third of the 20th C., but I think (and I don’t claim the idea is original with me) one of them was the closing of the frontiers. It seems to me that, until the end of the 19th C., many American men (and many non-Americans who came to America) had as part of their self-image a certain untamed wildness. If things got too bad, if some benign yet overbearing Widow Douglas tried too hard to “sivilize” him, he could always “light out for the territory.” Some did; most did not; but while that potential was there it seems to have formed the American popular image of what it is to be a man. Then, relatively suddenly, there was no “frontier” anymore; there was only Nebraska. You cannot escape from the Widow Douglas by moving to Nebraska; she (or her equivalent) is already there. Much genre fiction–including S&P–gives a place (if only an imaginary one) to this image of the American man as a noble savage (sometimes with more emphasis on the savagery, other times on the nobility).

The cultural stress that generates the flood of urban fantasy is different, but no less far-reaching. The women’s movement shattered traditional notions of what it is to be a woman–the roles and activities appropriate to women. And a good job, too: you won’t hear me complaining about it. But traditional gender roles were convenient because they give people a map with which to negotiate the chaotic territory of human relations. If the old map doesn’t work, some thinking and exploring are needed to create a new one (or maybe a set of new ones). That’s what I see happening with urban fantasy: its aboutness is part of the culture-wide redefinition of female identity. This includes issues of power but isn’t restricted to them.

Also, it has leather-clad chicks kicking ass. I call that a win-win.

Another fascinating post, James. I think you’re right about the rise of adventure fantasy (particularly sword-and-planet) as a response to the end of the frontier. The only frontiers left were those of the imagination. Even though Gene Roddenberry called space the “final frontier” it never was…

I’ve often thought of ERB’s Martian Chronicles as an allegory of the Old West, with the “red” Martians representing idealized versions of Native Americans, and the green Martians (and other colors) representing other aspects of the “savage” cultures that fascinated Americans ever since the first settlers arrived in the New World. In a very real way, Barsoom was the frontier of the Old West magnified to the Nth degree…complete with swords flashing and guns blazing.

Your thoughts on Urban Fantasy as an expression of changing female roles is fascinating. What about the whole “Steampunk” movement? Where does that fit in? I’ve never been able to wrap my head around these steam-powered behemoths that seem to be replacing more traditional fantasy series. (Yeah, I read “Perdido Street Station” and found it imaginatively interesting, but bleak as hell and entirely depressing.)

This whole Steampunk thing might be a response to the millenium changeover. That is, “traditional” fantasy usually based its creations on some variation of Medieval or Middle Eastern culture; maybe the fantasy genre is trying to “update itself” by placing its focus more on twisted urban steam-scapes where technology and its failures are integrated into the whole magical/heroism background. In the case of “Perdido,” it also seems to be a rejection of the entire concept of the “hero.” (All the characters are simply sad, screwed-up, and ultimatedly doomed. Is all Steampunk this anti-heroic?)

Personally, I still prefer my fantasies sans technology. Does that mean I’m hopelessly 20th Century?

What a fascinating article. I certainly never considered these potential similarities between sword and planet and urban fantasy. The closure of the frontier certainly sounds like a logical catalyst for the genre fiction of the time. Perhaps that is why stories like ERB’s Martian stories and REH’s Conan stories have such a deep sense of adventure and wonder to them. If the writer’s were consciously or unconsciously reacting to the idea that the undiscovered country was in many ways no more, it would in part account for the fact that one can pick up these stories today and feel that spirit of exploration and adventure in the pages.

I tend to have a pretty broad way of defining things, and that would be true for Steampunk as well. That being said I would answer John’s question about whether or not there is heroic steam punk with a recommendation to read James P. Blaylock’s Langdon St. Ives stories. I find them very heroic and if not wholly steampunk they certain contain elements of the steampunk genre.

Thanks, you guys, for the comments and kind words.

John: Interesting thoughts about Barsoom and steampunk. John Carter, of course, does step straight from the American southwest to Barsoom: there has to be a connection there. I’m not sure about the genesis of steampunk: it may be, as you say, just an attempt to get some new colors onto the fantasist’s palette. But they do seem to be pretty gloomy colors. (Of course, so were REH’s.)

Carl: Thanks for the Blaylock suggestion. I blush to admit I’ve never read anything by him, but the stuff mentioned on his Wikipedia page sounds pretty promising.

I guess the “problem” with Steampunk (IMHO) is not that it brought something new into the fantasy culture, but that tons of writers then jumped on it as the “new” way that fantasy “should be.” Hence, the current glut of Steampunk books that are crowding the bookstores shelves alongside all the Tolkien clones.

Carl: Thanks for the suggestion. I’ll have to check out Blalock’s St. Ives stories!

Fascinating analysis. I wonder though if searching for the same cultural antecedents in Steampunk and Sword and Planet isn’t a red herring. Perhaps a closer analogy would be between Steampunk and High Fantasy. If we see Fantasy as feeding a Luddite-like dread to technology’s overpowering influence in our lives, perhaps Steampunk is in some way an attempt to bridge the gap between our desire for Eden and our dependence on Machine. Could it be the extension of the internet as a medium for social bonding that triggered this change? As we realize that technology can feed the spirit as well as sap it we seek some rapprochement with what we have wrought, turning away from the Romantic and toward the Enlightenment.

[…] The Sword of Rhiannon by Leigh Brackett by Ryan Harvey Swordsmen in the Sky by Charles Saunders A Bout of Aboutness: Urban Fantasy and Sword-and-Planet by James Enge An Interview With Paizo publisher Erik Mona by Howard Andrew […]