Wormy: The Dragon‘s Dragon

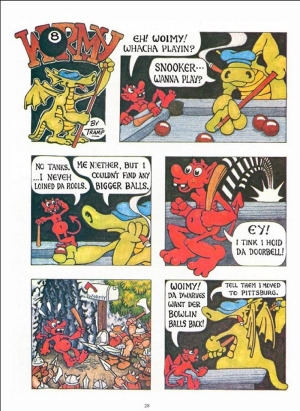

It begins with an imp, some dwarves, a stolen set of bowling balls, and a cigar-smoking dragon in a flat newsboy cap. It gets stranger from there, sprawling through an epic of long-jawed mudsuckers, oddly literate stonedrakes, bad puns, bounty hunters, and some of the most spectacular color comics pages you can imagine.

It begins with an imp, some dwarves, a stolen set of bowling balls, and a cigar-smoking dragon in a flat newsboy cap. It gets stranger from there, sprawling through an epic of long-jawed mudsuckers, oddly literate stonedrakes, bad puns, bounty hunters, and some of the most spectacular color comics pages you can imagine.

I’m talking about Wormy, a comic by David Trampier which ran in the back of Dragon magazine, one to four pages per month, from 1977 to 1988. Trampier, whose artwork helped define the feel of First Edition Dungeons & Dragons, created a lush, memorable tale, one that deserves to be better known today. You can see a large chunk of it here, though most of the comic seems to be offline.

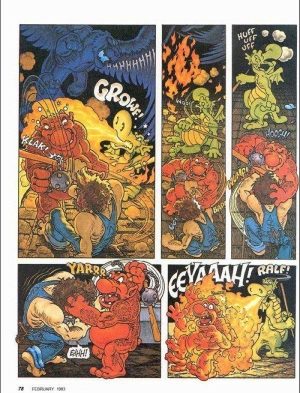

What was it about? As I said, it began with Wormy, a green dragon with a cigar, who’d stolen some bowling balls from a group of dwarves. The dwarves show up to try and get them back, which leads to complications involving a group of brutal but occasionally cunning card-playing ogres (Wormy steals their poker pot when they’re not looking), a minotaur, a talking bear in a Robin Hood hat, a whole community of trolls, and a Brooklyn-accented imp. Then somewhere in there one of the balls gets broken, and a demon comes spilling out. So when we cut to a wizard named Gremorly, “somewhere at the end of this weird world,” plotting to steal the dwarven treasure, we’re not that surprised.

The story ambles on, incorporating a hillbilly Cyclops named Ace—Wormy’s best friend, who’s accompanied by a talking cyclopean hound named Hambone—banshees on a haunted hill, and hints about Wormy’s past. It turns out the dragon’s a former gambler and wargamer; which may not sound bad, but in this world ‘wargaming’ means staging gladiatorial combats with trolls, and it’s been made illegal by Storm Giants, who we learn have put a bounty on Wormy’s head.

The comic’s first storyline, about Gremorly’s attempt to get his hands on the dwarven bowling balls, is complete in itself, though it leaves a number of questions unanswered and sets up subplots more thoroughly explored later. The second storyline is much larger in scope. It skips back and forth between Wormy’s attempts to build a model castle for his gaming, events at the troll city of Skeeter’s Grove, a group of giants looking for Wormy’s head, ogres who capture trolls to sell as slaves to wargaming giants, and a number of other plot strands.

The comic’s first storyline, about Gremorly’s attempt to get his hands on the dwarven bowling balls, is complete in itself, though it leaves a number of questions unanswered and sets up subplots more thoroughly explored later. The second storyline is much larger in scope. It skips back and forth between Wormy’s attempts to build a model castle for his gaming, events at the troll city of Skeeter’s Grove, a group of giants looking for Wormy’s head, ogres who capture trolls to sell as slaves to wargaming giants, and a number of other plot strands.

Sadly, the tale was never concluded. For reasons that remain unclear, Trampier severed all ties with Dragon magazine and the world of gaming. Wormy remains a stunning but truncated work. It’s a pity; you can see the plots all beginning to converge, but Trampier’s skill at making his plots dovetail in unexpected ways leaves you wondering how they’d actually work themselves out. You think you can see how things are building to a climax, if not exactly how they’re going to resolve themselves—but then the comic ends right in the middle of unexpectedly re-introducing a major subplot, which complicates the ongoing story.

So much for what Wormy is. Why’s it still worth talking about?

Because it’s a stunning piece of work. Because the art is beautiful. Because the storytelling was deft and sure-footed. Because the writing was convincing, in the way it built up a world, established character, created a mood, and used dialect to strengthen dialogue. Because it was very funny, and often touching.

Consider the craft in it. The first few pages are relatively weak, with awkward character posing and overlarge word balloons, but the look of the strip swiftly improves, along with the complexity of the story. Trampier’s grasp of the language of comics matures remarkably. His panel transitions are strong; you don’t get lost going from image to image.

Consider the craft in it. The first few pages are relatively weak, with awkward character posing and overlarge word balloons, but the look of the strip swiftly improves, along with the complexity of the story. Trampier’s grasp of the language of comics matures remarkably. His panel transitions are strong; you don’t get lost going from image to image.

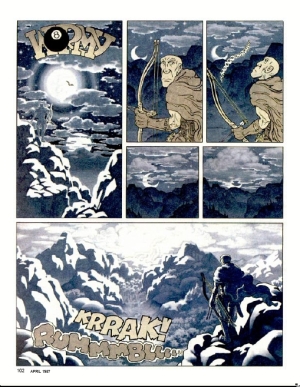

His choices of camera angles are excellent; always dramatic, catching strong angles for showing a character’s emotion through body language or expression. He tends to prefer medium shots, especially for Wormy, but not to an extent that it becomes predictable or repetitive. That framing allows him to show a character’s full figure, often a good idea in humor cartooning.

Panel layouts are very traditional, rectangles and squares with wide white gutters, but very readable and well-designed for a page the size of Dragon magazine. When Trampier wants to give a moment more power, he gains real impact by opening up the layout to larger panels or splash pages, or subtly allowing a character to spill over the panel borders. Placement of word balloons, an often-overlooked skill, is solid; you rarely get confused about what to read first, and the positioning of the words with the images works to guide the reader’s eye through the page.

As illustration, the pages are eye-popping. The design of the characters is wonderful. You get a sense of who they are at a glance. Their body language and acting is also clear and expressive, which is notable given how few of the characters have human features.

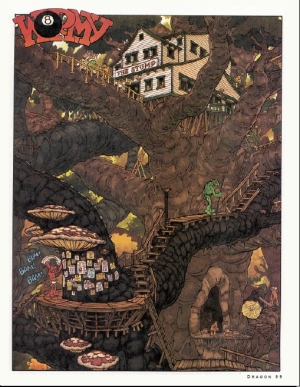

The design of the world is spectacular. Wormy’s cave, the troll city of Skeeter’s Grove, a forest of towering “yigdrazzle trees,” a haunted hilltop—all of these things are well-conceived, and depicted with a mix of great draughtsmanship and solid cartooning. The result is not only tremendous detail in the rendering, and a sense of depth, but also a feeling of life and movement.

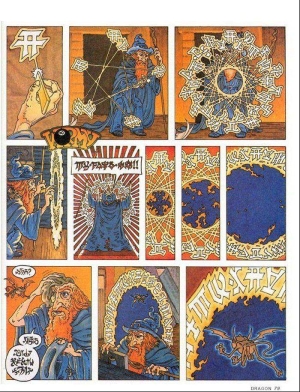

Add to that Trampier’s visual playfulness. He has a knack for depicting magic as truly otherworldly, a thing of mists and runes and odd perspectives. And in a strip where some of the characters are giant-sized and some aren’t, his sense of the way they interact with different-scaled environments works well.

Add to that Trampier’s visual playfulness. He has a knack for depicting magic as truly otherworldly, a thing of mists and runes and odd perspectives. And in a strip where some of the characters are giant-sized and some aren’t, his sense of the way they interact with different-scaled environments works well.

But what really makes the strips visually arresting is Trampier’s color sense. The art is bright, expressive, and yet at the same time subtle. Color works to create atmosphere and evoke emotion. Moonlight on clouds, deep woods, a dragon’s treasure hoard—Trampier uses bright and varied colors to make all these things come to life.

Given the technological limitations of the printing technology then available for American mainstream comics, it’s not impossible that these might have been the most lavishly-colored North American comics of the time. Certainly Trampier’s skill with color, his ability to make colors pop while still feeling natural, is phenomenal. Arguably, it’s better than much current coloring in comics, in that the rich hues harmonise with his linework while still giving depth, indicating light sources, and generally creating a world you can almost touch.

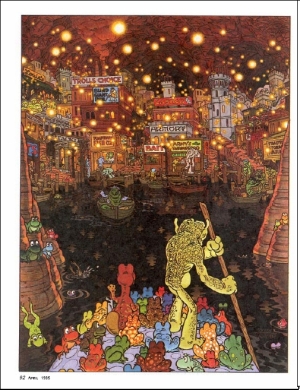

As a writer/artist, a true cartoonist, Trampier’s able to execute some fine effects that come so much easier when one hand is both scripting and illustrating. He can pace his story as he likes, and work in comedy moments and character moments. Above all, he can plan scenes for himself that he knows he’ll be able to work visual magic with—most notably, a wordless sequence of frogs gathering on the carcass of a giant fish, itself being poled by a troll along an underground river, which suddenly widens to reveal a subterranean city.

As a writer/artist, a true cartoonist, Trampier’s able to execute some fine effects that come so much easier when one hand is both scripting and illustrating. He can pace his story as he likes, and work in comedy moments and character moments. Above all, he can plan scenes for himself that he knows he’ll be able to work visual magic with—most notably, a wordless sequence of frogs gathering on the carcass of a giant fish, itself being poled by a troll along an underground river, which suddenly widens to reveal a subterranean city.

Trampier’s conception of his world, its depiction in both story and art, is excellent. It has its own logic, its own coherency. It clearly derives from early Dungeons & Dragons—ogres, giants, regenerating trolls, and so on—but by showing things from the monsters’ point of view, it creates something new. Wormy’s not just a wise dragon, he’s a streetwise dragon. More precisely, by giving his monsters original perspectives, vivid personalities, and sharp dialogue, Trampier creates something that’s much more than a gaming comic. It uses the givens you might find in a lot of ’80s fantasy, but does so in its own way, with a unique voice.

Technically, the structure of the strip grows more sophisticated. After the first storyline, about eighty pages, Trampier broadens his world and his cast of characters. A host of new subplots spring up, and he deftly skips among his plot strands, only to slowly start drawing them together later, introducing connections where you don’t expect them. The pace is slow, but deliberate, and feels somehow real.

This may derive from one of Trampier’s influences. Apparently Trampier’s mentioned an appreciation for Walt Kelly’s seminal strip Pogo; certainly it’s visible in his work. I’d guess some of his other influences might include American underground comix artists, particularly Vaughn Bodé, and perhaps also early Disney and traditional ‘bigfoot’ animation. (No trace of manga influence here.)

This may derive from one of Trampier’s influences. Apparently Trampier’s mentioned an appreciation for Walt Kelly’s seminal strip Pogo; certainly it’s visible in his work. I’d guess some of his other influences might include American underground comix artists, particularly Vaughn Bodé, and perhaps also early Disney and traditional ‘bigfoot’ animation. (No trace of manga influence here.)

On the other hand, there’s a feel to the strip not unlike other fantasy comics at the time; things like Elfquest, the early Cerebus, or Phil Foglio’s free adaptation of Robert Asprin’s Mythadventures. The mix of fantasy, humour, and adventure feels similar.

Of course, Trampier’s best known for his designs for Dungeons & Dragons artwork; the original cover of the Player’s Handbook, in particular, as well as spot illustrations in the PHB, the Dungeon Masters Guide, and the Monster Manual. There’s an obvious correlation in subject matter with Wormy, but also a similarity of technique; I think a lot of people remember those illustrations fondly because they evoked a world from a single image. Wormy has much the same effect.

It was a great comic in its time; and looking back at it now, it’s still excellent work. Sadly, because it only appeared a few pages at a time in Dragon magazine, and twenty or thirty years ago at that, it’s less known today than it perhaps should be. It’s also unfortunate that Trampier seems to have turned away from art and gaming. A few years ago, a message board post suggested that Trampier might be interested in having a Wormy collection published, and even in completing the story. I can only hope that things work out to bring Wormy back, and finally bring the story to a conclusion.

Fabulous work, Matthew. I’m a huge Wormy fan… it’s one of the neglected treasures of the genre, and no mistake.

There’s been whisperings of a Wormy collection for decades. I hope it happens, but I admit I don’t have my hopes up.

Awesome work on this article Matthew.

As for Trampier, he certainly isn’t the only one from those lost gaming years to have turned their backs on the industry, although I believe he has done so more completely than the rest. A sad note, to be sure, but one I can understand. Being an iconic gaming artist can certainly bring out the loonies.

I have loved Trampier’s work for 30 years now.

It is his visuals I think of when I think of D&D.

And Wormy…well Wormy was, is, tremendous.

Like I said in a post a few weeks ago, it is a shame he decided to drop off the grid all those years ago.

Thanks for the words on the post! I was happy to revisit Wormy, and find that it was, if anything, even better than I remembered; the sheer level of craft in it stunned me. John, the story I heard (meaning: the story I found on the internet) was that Trampier was intending to self-publish a collection of the first hundred or so Wormy strips back when he was still doing the comic, but found that the process was more expensive than he’d thought. Which would track; as I noted, that kind of colour work would have been rare, and I’d think expensive to print. And at that point, trade paperbacks of comics were unusual, if not unheard of in North America.

Scott, I certainly know what you’re saying about gaming industry veterans. I don’t know if it’s just me, though, but it seems like more and more figures from those days are finding their way back to the field (Erol Otus, for example). I don’t know the field as well as many, though, so I could well be wrong; still, I’d like to think the Old School Renaissance is having an effect in not only bringing old material back to light, but also re-inspiring old creators.

TW, I know what you mean about the look of D&D. For me, that picture of Emirikol the Chaotic in the DMG is just so evocative, hinting at a story … hinting at several possible stories, actually. There’s a solidity to it, a sense that I’m looking at magic existing alongside flesh and blood characters, that I don’t often get from current D&D art.

[…] Wormy ran in the back of TSR’s Dragon magazine (then called The Dragon) from September 1977 to April 1988. I loved it at the time, and I still consider it one of the best gaming-related comics I’ve ever encountered. Stylistically, it combined the rich colors, clean lines, and lush backgrounds reminiscent of Miyazaki with the sort of comically exaggerated characters found in Bakshi’s cartoons. His characterization and dialogue were equally vivid. (For a more adept technical explanation of Trampier’s strengths as a cartoonist, click here.) […]

[…] I do know it that in the late 1980s, during his run with the Wormy comic for TSR’s Dragon magazine, Trampier suddenly went off the grid. At the time, he’d have […]