The Power That Preserves by Stephen R. Donaldson

And so we come to the end of the First Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever (follow the links to read my reviews of the previous two books, Lord Foul’s Bane and The Illearth War). While not an upbeat book by any degree The Power That Preserves (1977) provides a satisfying and hope-filled conclusion to a series heretofore characterized mostly by loss and despair. Those elements still figure heavily in this story, but this time around they more clearly serve to prepare Covenant for the confrontation with Lord Foul.

And so we come to the end of the First Chronicles of Thomas Covenant the Unbeliever (follow the links to read my reviews of the previous two books, Lord Foul’s Bane and The Illearth War). While not an upbeat book by any degree The Power That Preserves (1977) provides a satisfying and hope-filled conclusion to a series heretofore characterized mostly by loss and despair. Those elements still figure heavily in this story, but this time around they more clearly serve to prepare Covenant for the confrontation with Lord Foul.

The events of the crushing, sorrow-filled The Illearth War have left Thomas Covenant a broken man. He is pulled back and forth by the weight of what he did and his continued disbelief in the Land’s reality. Compelled by his reawakening need for human contact, he falls into a sort of madness and takes to haunting the woods and backstreets of his town, a place from which he’s been exiled because of people’s fear of his disease. When he stops taking the meds that suppress it, his leprosy is triggered.

While trying to save a little girl being menaced by a timber snake Covenant is summoned to the Land by the new High Lord, Mhoram. Under command of the Raver-possessed Giant, Satansfist, a vast army has destroyed Revelwood and laid siege to Revelstone. For weeks Lord Foul has called down perpetual winter on the Land and sent packs of marauders to kill any who defy his will.

Covenant insists he will help the Land, but must be allowed to return home and save the girl first. He does, but is poisoned himself. Once he’s satisfied she is safe, he says, “Come and get me. It’s over now.,” and is brought back to the Land. But he doesn’t arrive back in front of the Lords and inside the besieged Revelstone. Instead, he is called back to Kevin’s Watch where he first arrived in the Land in Lord Foul’s Bane. This time he has been summoned by Triock, one-time suitor of Lena (the woman he raped), and the Giant Saltheart Foamfollower. After he helps them fight off a vicious attack on Mithil Stonedown, Covenant decides the time has finally come to take a stand.

Snow slowly thickened in the air. The flakes danced like motes of obscurity across Covenant’s vision, and the strain of his fierce star made his unhealed forehead throb as if his skull were crippled with cracks. But he did not relent, could not relent now. “There’s only one good answer to someone like Foul.” Yet in spite of his anger, he found that he could not meet Foamfollower’s gaze.

“What answer?”

Involuntarily Covenant’s fingers bent into claws. “I’m going to bring Foul’s Creche down around his ears.”

He heard the surprise and incredulity of the Stonedownors, but he ignored them. He listened only to Foamfollower and the Giant said, “Have you learned then how to make use of the white gold?”

With all the intensity of conviction he could muster, Covenant replied, “I’ll find a way.”

The dual storylines of Covenant’s quest into the literal heart of darkness in the Land while in possession of a magic ring needed to destroy the dark lord, and the Lords’ defense of the great fortress, Revelstone, give The Power That Preserves a striking structural similarity to The Return of the King. While the similarities in Terry Brook’s The Sword of Shannara read close to plagiarism, those same things feel like a true homage in Donaldson’s works. He takes the familiar bones of Tolkien’s work and builds a new creation over them. Covenant is a reluctant hero and someone who has caused great harm during his journeys to the Land. The focus here is not on a Frodo-like selfless perseverance, but an acceptance of responsibility and understanding of despair.

The dual storylines of Covenant’s quest into the literal heart of darkness in the Land while in possession of a magic ring needed to destroy the dark lord, and the Lords’ defense of the great fortress, Revelstone, give The Power That Preserves a striking structural similarity to The Return of the King. While the similarities in Terry Brook’s The Sword of Shannara read close to plagiarism, those same things feel like a true homage in Donaldson’s works. He takes the familiar bones of Tolkien’s work and builds a new creation over them. Covenant is a reluctant hero and someone who has caused great harm during his journeys to the Land. The focus here is not on a Frodo-like selfless perseverance, but an acceptance of responsibility and understanding of despair.

Covenant’s march to Foul’s Creche is beset by grievous hardships and confrontations. Through ice, muck, and fire he marches, facing enemies physical and spiritual. His sins in the Land, all emanating from his original one, the rape of Lena, resurface and scour his soul with remorse and sorrow. But he is also strengthened by these events and directed toward the right way to confront Lord Foul.

Power adopts the trappings of epic high fantasy even more than did The Illearth War. There were battles in the earlier book, but in this one they are bigger and more elaborate. The siege of Revelstone is described in horrible detail as, by both brute force and insidious magecraft, the forces arrayed against the Lords by Satansfist attempt to overthrow the great fortress city. Catapults throw corrosive slime against the walls, and great hordes of Cavewights and magic-twisted humans storm them.

The near collapse of morale under the Raver’s magical assault is more terrible than the attacks on the walls:

Though it moved slowly, the hungry agony of the attack was now only scant yards from Revelstone’s walls. Through his feet, Mhoram could feel the Keep moaning in silent immobility, as if it ached to recoil from the leering threats of those veins.

But that was not why Mhoram stood throughout the long night exposed to the immedicable gall of the wind. He could have sensed the progress of the assault from anywhere in the Keep, just as he did not need his eyes to tell him how close the inhabitants of the city were to gibbering collapse. He watched because it was only by beholding Satansfist’s might with all his sense, perceiving it with all his resources in all its horror, that he could deal with it.

When he was away from the sight, dread seemed to fall on him from nowhere, adumbrate against his heart like the knell of an unmotivated doom. It confused his thoughts, paralyzed his instincts. Walking through the halls of Revelstone, he saw faces gray with inarticulate terror, heard above the constant, clenched mumble of sobs — children howling in panic at the sight of their parents, felt the rigid moral exhaustion of the stalwart few who kept the keep alive — Quaan, the three Lords, most of the Lorewardens, lillianrill, and rhadhamaerl. Then he could hardly master the passion of his futility, the passion which urged him to strike at his friends because it blamed him for failing the Land.

Power shifts, chapter to chapter, between Covenant’s trek into Foul’s demesne and Lord Mhoram’s struggle against Satansfist. More than the previous two books, this one moves rapidly toward the inevitable showdowns between the two pairs of antagonists. While parts of The Illearth War showed that Donaldson could write speed and action, nothing prepared me for the ceaseless momentum in this book. Once Covenant accepts the summons to the Land there is practically no letup.

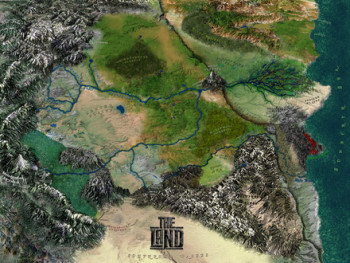

In The Illearth War, with so many pages dedicated to the anguish of Covenant and Troy, there was less space devoted to depicting the majesty of the Land than in Lord Foul’s Bane, but Donaldson finds time do some more in Power. Much of it comes during the final approaches to Foul’s Creche, through such evocatively-named locales as the Ruin Wash and Hotash Slay. There are also moments of delicate beauty. Despite the severe cold, the Land itself is still alive in certain places, as we see during Covenant’s stay in the haunting forest of Morrinmoss:

In The Illearth War, with so many pages dedicated to the anguish of Covenant and Troy, there was less space devoted to depicting the majesty of the Land than in Lord Foul’s Bane, but Donaldson finds time do some more in Power. Much of it comes during the final approaches to Foul’s Creche, through such evocatively-named locales as the Ruin Wash and Hotash Slay. There are also moments of delicate beauty. Despite the severe cold, the Land itself is still alive in certain places, as we see during Covenant’s stay in the haunting forest of Morrinmoss:

For a time, the gleaming hovered over him as if it were curious about his immobility. Then it spangled away into the depths of the trees, leaving him clapped in dolorous dreams. While he slept, the light mounted until the trunks seemed to be reaching toward him with their illumination, seeking a way to absorb him, rid the ground of him, efface him from the sight of their hoary rage. But though they glowered, they did not harm him. And before long a feathery scampering came through the branches and the moss. The sound seemed to reduce the trees to baleful insentience; they withdrew their threatening as a host of spiders began to drop lightly onto Covenant’s still form.

Guided by gleams, the spiders swarmed over him as if they were searching for a vital spot to place their stings. But instead of stinging him, they gathered around his wounds; working together they started to weave their webs over him wherever he was hurt.

In a short time, both his feet were thickly wrapped in pearl-gray webs. The bleeding of his ankle was stanched, and its protruding bone-splinters were covered with gentle protection. A score of the spiders draped his frostbitten cheeks and nose with their threads, while others bandaged his hands, and still others webbed his forehead, though no injury was apparent there. Then they all scurried away as quickly as they had come.

In Thomas Covenant, a character morally and physically repellent, and his engagement with the Land and its inhabitants, Stephen R. Donaldson carries on a thousand-page exploration of sin, guilt, temptation, obligation, responsibility, forgiveness, and redemption. These are heady issues to attach to a work in a genre that exists primarily to entertain, but it never feels inappropriate, and the story Donaldson tells is able to bear their weight. Too often, a story with some larger intent than just enjoyment falls into didacticism.

In Thomas Covenant, a character morally and physically repellent, and his engagement with the Land and its inhabitants, Stephen R. Donaldson carries on a thousand-page exploration of sin, guilt, temptation, obligation, responsibility, forgiveness, and redemption. These are heady issues to attach to a work in a genre that exists primarily to entertain, but it never feels inappropriate, and the story Donaldson tells is able to bear their weight. Too often, a story with some larger intent than just enjoyment falls into didacticism.

Over the years I have seen these books dismissed for putting a rapist into the position of hero. But that is a point of view that fails to see the true nature of what Donaldson is exploring. There is no cheap grace in Thomas Covenant’s ascent from rapist to savior. Every movement he makes toward redemption comes with its own additional burden. Even when there is forgiveness for Covenant it doesn’t erase the damage he has done. Sins he commits in Lord Foul’s Bane don’t fade with that book’s end, but last for decades, often growing in severity. Sin has weight that cannot simply be lifted by a wave of the hand, a change of heart, or a sunny disposition. To just dismiss Covenant for being a rapist calls into question the very possibility of redemption.

This trilogy is a triumph of imagination. While inspired by Tolkien’s works, Donaldson created a world that seems built of some lost myth cycle, not warmed over medievalisms or role-playing conventions. The Land is a striking, unique place that feels like nowhere else in fantasy. There are no knights in shining armor or secret heirs to the throne. The only barbarians are so smitten with the pure generosity of the Lords of Revelstone that they take up an oath to protect them at all costs. Donaldson conveys the beauty of the Land and its people’s devotion to it with such joy and wonder that when he takes us to places ravaged by Foul, the wrongness is palpable. You can almost smell the sulfur and brimstone coming off the page. The Land is a place that will haunt me, just as it did Covenant, for a very long time.

When I drafted my list of epic high fantasy novels I wanted to read, these were the only ones I hadn’t read all the way through in the past. In fact, I had previosuly only read Lord Foul’s Bane and that was only a few years ago. These books had been huge, but I avoided them until now. Having read them, I can only hang my head that I didn’t give them more of a chance before, and that I gave so much credence to the criticisms of them. That these books are not more widely read today is a shame. If you read epic fantasy but haven’t read these, I say you should. You may hate Thomas Covenant, you may even want to throw the books against the wall, but you will be rewarded with some of the most thought-provoking storytelling to ever grace the genre.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read his thoughts about epic high fantasy here.

Kind of ridiculously overwritten, but Donaldson has so many amazing set-pieces that I still remember to this day.

Will you be proceeding to the Second Chronicles?

Your point about questioning even the possibility of redemption has my attention. At 13, I didn’t need redemption from nearly enough bad moments or nearly enough bad tendencies to see the point. I knew I had no interest in forgiving the people who had wronged me most — and there were two real humdingers — and I didn’t want to live in a world where they could ever be redeemed.

It’s just not a young person’s series.

@Joe – Yeah, but it’s one of the few cases of things being turned up to 11 and it makes sense. I will be reading the Second Chronicles sooner rather than later, I don’t want to get too far out from these before getting started.

@Sarah – Exactly, that’s spot on. I really wonder what my reaction would have been if I had stuck it out like you did at that age.

[…] Slime Watch (Black Gate) The Power That Preserves by Stephen R. Donaldson — “Over the years I have seen these books dismissed for putting a rapist into the […]

Signed up just to comment on this.

What a great, insightful review!

I’m not a fantasy reader. I’d read Lord of the Rings and a few other fantasy books as a child. In adulthood I’ve tried several other series but have found them way to conventional with cliched characters.

I just got done reading this trilogy and I have to say it blew me away.

The main reason being the protagonist. In all my years of reading I’ve never come across a character quite like him. Immediately we dislike him – cantankerous to the extreme, and a rapist. However, as the novels progress, sympathy does creep in. Lest we forget, he is a leper, in dark dark place, hating himself, devoid of human contact or warmth, and betrayed and shunned by those he loved. It was a real moral struggle for me, the reader, to balance my sympathy for him with his terrible deed. You are right though, his sins pile up, have enormous exponential repercussions decades later and are never whitewashed away. In the end we reach an uncomfortable conclusion, where Covenant has not quite redeemed himself in his own mind, but is able to come to terms with his sins.

I also think it is about coming to terms with his leprosy. I think the whole trilogy could be read as an allegory for Covenant’s internal struggle with leprosy. Lord Foul is his own self-loathing and disgust, and the Desecration of the Land is a metaphor for giving up hope/suicide. What do you think?