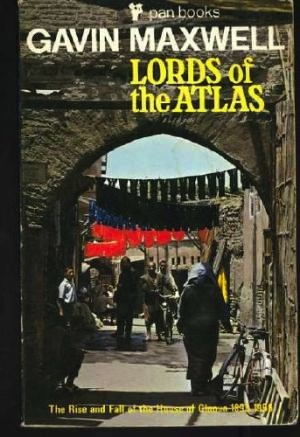

When Morocco Really Was Adventurous: Reading Lords of the Atlas

For people who have never been there, Morocco conjures up images of decadent ports, imposing casbahs, mysterious medinas, and mountains filled with bandits. It’s a mystique the tour companies like to perpetuate for this modern and rapidly changing country.

For people who have never been there, Morocco conjures up images of decadent ports, imposing casbahs, mysterious medinas, and mountains filled with bandits. It’s a mystique the tour companies like to perpetuate for this modern and rapidly changing country.

I feel like a bit of a cheat tagging my series of Morocco posts as “adventure travel,” but I’m a blogger and that tag brings in the hits. While Morocco is safe and easy to travel in, it wasn’t so long ago that the mystique was the reality. A classic study of this freebooting era is Gavin Maxwell’s Lords of the Atlas.

Researched in the 1950s, it looks at the twilight era of the old Morocco. The book opens with a slave unlocking the gate to an aging, all-but-abandoned Casbah in the remote Atlas Mountains. This man was one of the last retainers of the Glaoui family, which for two generations grew an empire in Morocco’s rugged mountains, became pashas of important cities, and even played kingmaker.

Maxwell has an eye for lurid detail, especially beheadings. You can feel the writer’s enthusiasm when he speaks of how, just a little over a century ago, the city gates of Morocco would be festooned with the heads of criminals and traitors. The heads had been preserved in salt, a job reserved for the Jews. The Jewish quarter even earned the name mellah, Arabic for “salt.” Even well salted, the heads would eventually rot and fall down into the crowd below, once almost hitting a delegation from England.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, Morocco was a unified country only in name. The Sultan directly controlled only that part of Morocco that his personal troops and his own political skills could manage. This generally included northern Morocco up to the edge of the Atlas Mountains. This was referred to as the Bled el mahkzen, “the country of the palace.” Even this home territory required constant supervision and a wise Sultan had several capitals.

The rest of the country, including the Atlas, its three major passes between north and south, and the southern desert beyond, were called the Bled es-siba, “the uncontrolled lands.” This land was made up of independent tribes and a few towns that were more like city states. They would not pay taxes to the Sultan unless forced to.

“Arabs Skirmishing in the Mountains” by Eugène Delacroix, 1863.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

If the Sultan wanted taxes from this region that was supposedly under his rule, he had to invade it. His standing armed forces were generally small, so he called up all the warriors in the Bled el mahkzen, plus large numbers of mercenaries from sub-Saharan Africa, and went on a harka. The harka is best described by another writer, Angus Stewart, in his Tangier: A Writer’s Notebook.

The harka — literally the ‘burning’ was a Moroccan peculiarity dating back to the Idrissid dynasty of the eighth century. Politely, its function was tax-gathering. But in the bled es-siba — uncontrolled lands — this could only be accomplished by bloody subjugation. The nucleus of such expeditions comprised the Sultan himself, his harem, ministers, personal guard regiments, cavalry and artillery, and a mighty host of lesser, but loyal soldiery. The composition of the majority changed constantly as the fire raged upon its way. Tribe X would lend strictly temporary allegiance to the Sultan for the convenience of decimating their personal enemy tribe Y. In this way tribe X might also save some fraction of their crops and livestock. Tribe Y, if they were lucky, would be left with a few old women and very young children. The result was self-evident: no trouble from the Ys for at least a generation. Razing of crops and livestock had a similar motive. The dissidents would be too preoccupied with starvation to wield flintlocks; or, as the saying went, ‘An empty sack cannot stand up.’

The harka was generally inflicted on the open southern territory, but to get there the Sultan had to first cross one of the three passes of the Atlas, each held by its own Berber tribe. One of these was the House of Glaoui.

It was a failed harka that gave the Glaoui clan a chance to become more than the guardians of a mountain pass. In 1893, Sultan Moulay Hassan was returning from an expedition to the south. The harka had not gone well and the army was short on food. Sickness and discontent spread through the camp. His exhausted, hungry men were close to rebellion and he needed to get them to the north where he could feed and pay them. Passing through the Atlas would be a necessary gamble. The Berbers might fall on his weakened army, who might very well switch sides in the process. The Sultan picked the pass controlled by the Glaoui as the tribe least likely to stab him in the back.

To his surprise and relief, they gave him food and safe passage. As a reward he presented the Glaoui with a Krupp cannon. This proved a propitious gift because it gave them an edge over the rival two tribes, who had no cannon. Plus the mud brick fortresses of the Atlas, which were proof against musket fire, would crumble in the face of German artillery shells.

One of the Casbahs of T’hami El Glaoui in Ouarzazate.

Photo courtesy Bjørn Christian Tørrissen

The stage was set, but more actors were to appear. As the Glaoui spread their influence across the Atlas and the south through a combination of intrigue and brutality, to the north the French and Spanish were expanding their colonial influence. By 1911 the French had occupied Fez and the Sultan was a mere puppet.

The leader of the Glaoui, T’hami El Glaoui, played off one side against the other. When the pretender Sultan El Hiba rallied the southern tribes, T’hami at first acted sympathetic to him. Reassured, El Hiba marched on Marrakesh in 1912 and took the European residents captives. T’hami El Glaoui waited until the French had defeated El Hiba’s army before grabbing the hostages and delivering them safely to the French. The colonial government rewarded him by making him Pasha of Marrakesh and named a puppet as Sultan. This suited T’hami El Glaoui just fine. A weak Sultan in the north was preferable to a strong Sultan in the south.

Such was the diplomatic course he would take for the next forty years. He became France’s ally to subjugate the southern tribes, at great personal profit to himself, and supported the country in both world wars. When the independence movement gained momentum he opposed it. When the nation finally became independent of France in 1956, T’hami El Glaoui had to change tack. How he would have maneuvered in the very different circumstance in which he found himself we will never know, because he died the same year.

Maxwell’s rich prose brings this tale of intrigue, deception, and war to life–the harems, the massacres, the spendthrift Sultans, the assassinations, the dank torture chambers. It isn’t a pretty picture, and the book is not widely circulated in Morocco, but it does show how much Morocco has progressed in the span of a human lifetime.

Lords of the Atlas is essential reading for those who want to understand Morocco, and makes a great read for anyone interested in history.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles, including his post-apocalyptic series Toxic World that starts with the novel Radio Hope. His historical fantasy novella The Quintessence of Absence, was published by Black Gate. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page.

I envy you your travels. Douglas Porch’s magisterial THE CONQUEST OF MOROCCO is an excellent book.