Wandering the Worlds of C.S. Lewis, Part III: Dymer

This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis. I began on Sunday with a look at his juvinilia, published in Boxen: Childhood Chronicles Before Narnia, and then yesterday looked at his first book of lyric poems, Spirits in Bondage. Today I round out my look at Lewis’ early works with some thoughts on the first of his long narratives to be published, an epic poem called Dymer, written while he was struggling to get a job as a professor and while he was in the process of moving from strict atheism to belief in Christianity. I also take a look at his short story “The Man Born Blind,” probably written soon after Dymer was published.

This is the third in a series of posts about the fictions of C.S. Lewis. I began on Sunday with a look at his juvinilia, published in Boxen: Childhood Chronicles Before Narnia, and then yesterday looked at his first book of lyric poems, Spirits in Bondage. Today I round out my look at Lewis’ early works with some thoughts on the first of his long narratives to be published, an epic poem called Dymer, written while he was struggling to get a job as a professor and while he was in the process of moving from strict atheism to belief in Christianity. I also take a look at his short story “The Man Born Blind,” probably written soon after Dymer was published.

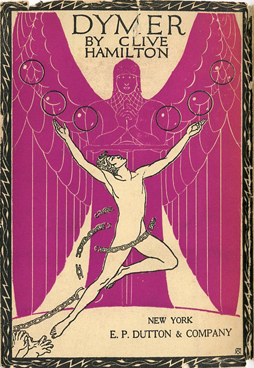

In 1922 C.S. Lewis recorded in his diary that he had “started a poem on ‘Dymer’ in rhyme royal.” His phrasing’s interesting: a work “on” Dymer, as though it were a well-known subject. “Dymer” was already a familiar story to him. He’d written it out in prose in 1917, one of his first mature prose works to use modern diction and avoid the archaisms of William Morris’ novels. Late in 1918 he wrote in a letter that he’d just completed a “short narrative, which is a verse version of our old friend Dymer, greatly reduced and altered to my new ideas. The main idea is that of development by self-destruction, both of individuals and species.” Nothing of this version seems to have survived in the 1922 poem, which was finished in 1925 and published in 1926 to mixed reviews.

Dymer is a fast-moving poem, and it’s to Lewis’ credit that few or none of the rhyme royal stanzas seem to solely serve the plot; each stanza has some image or line striving to catch the eye. On the other hand, the striving’s often too obvious. The quick pace also means some material feels underexplored, while incidents on the whole come too quickly. Much as one must grant some poetic license, questions can’t help but arise. Some key events reported to Dymer feel underexplored, and some plot elements feel abandoned too easily. Symbolism is occasionally obtrusive. Lewis himself wrote in his diary on June 22, 1922 that he was dissatisfied at “having now left the myth and being forced to use fiction[.]”

There are some very fine moments in the poem. A vigil on a battlefield near the very end seems to recall his experiences in World War One, perhaps more effectively than anything in Spirits in Bondage did. But then there are also some bad passages; in particular, I’m thinking of the opening lines of II. 33, when Lewis uses a peculiar version of the pathetic fallacy to represent Dymer having sex. (“The same night swelled the mushroom in earth’s lap / And silvered the wet fields: it drew the bud / From hiding and drew on the rhythmic sap …”) Overall, I think the poem’s interesting, in part because of the complexity and even obscurity of its plot structure.

There are some very fine moments in the poem. A vigil on a battlefield near the very end seems to recall his experiences in World War One, perhaps more effectively than anything in Spirits in Bondage did. But then there are also some bad passages; in particular, I’m thinking of the opening lines of II. 33, when Lewis uses a peculiar version of the pathetic fallacy to represent Dymer having sex. (“The same night swelled the mushroom in earth’s lap / And silvered the wet fields: it drew the bud / From hiding and drew on the rhythmic sap …”) Overall, I think the poem’s interesting, in part because of the complexity and even obscurity of its plot structure.

The story begins in a highly-regulated city based on Plato’s Republic. There, one April, a nineteen-year-old youth, Dymer, laughs, semi-accidentally kills his teacher, and leaves for the woods beyond the city. Stripping naked, inarticulate, he glories in nature, then follows a mysterious sweet music to a domed palace. In Canto II he finds rich clothes and fine food in the palace, debates his next move with himself, and comes to a darkened chamber where he discovers an unseen woman to whom he makes love. In Canto III he wakes the next morning, goes outside, and is lost in the palace when he tries to return, repeatedly encountering a monstrous old woman, an “old, old matriarchal dreadfulness,” as he vainly tries to find his lover of the night before. Finally, after the old woman refuses to speak to him, he fights with her and flees the palace, “beaten, broken, past desire of healing[.]”

In Canto IV Dymer survives a storm, then finds a dying man who tells him that his murder of his teacher inspired a large-scale rebellion in his home city and a mass battle, with the insurgents, led by a man named Bran, having finally left the city earlier that morning. In Canto V Dymer struggles with a suicidal depression before recapturing a sense of joy and a desire to live. Then, in Canto VI, he meets a magician who tempts him with dreams. Dymer proclaims a desire to atone for his sins instead, but spends the night in the man’s house before waking to describe to the wizard a dream that has now led him to reject dreams entirely.

(Two things are worth noting about this dream with reference to later stories. First, an idealised female figure in the dream tells Dymer that for dreams only “did men love / The shadow-lands of earth,” a term that Lewis would use in the last Narnia book. Second, in Dymer’s telling, the dream’s a wish-fulfilment dream that he rejects not only out of an awareness that all that’s wonderful in dreams arises solely from his own desires, but because the wonders give way to sex fantasies: “King Lust with his black, sudden, serious stare.” These objections seem almost contradictory — Dymer says that the dream is insufficient because it merely comes from his own head, and then says that the dream was taken over by an emotion beyond his control. In other words, it’s both too much a product of his conscious personality and also too subject to his unconscious. But this struggle with fantasies hijacked by sexuality will turn up in The Pilgrim’s Regress.)

(Two things are worth noting about this dream with reference to later stories. First, an idealised female figure in the dream tells Dymer that for dreams only “did men love / The shadow-lands of earth,” a term that Lewis would use in the last Narnia book. Second, in Dymer’s telling, the dream’s a wish-fulfilment dream that he rejects not only out of an awareness that all that’s wonderful in dreams arises solely from his own desires, but because the wonders give way to sex fantasies: “King Lust with his black, sudden, serious stare.” These objections seem almost contradictory — Dymer says that the dream is insufficient because it merely comes from his own head, and then says that the dream was taken over by an emotion beyond his control. In other words, it’s both too much a product of his conscious personality and also too subject to his unconscious. But this struggle with fantasies hijacked by sexuality will turn up in The Pilgrim’s Regress.)

Dymer flees the wizard, and in Canto VIII meets a spirit in the form of a woman, “The loved one, the long lost.” He speaks with her; she tells him that he is still in a dream, and disappears. Feeling born again, he goes to rest in a cemetery, where he’s caught up in a great wind, briefly sees visions, and is at last deposited before an angelic sentry guarding against “beasts of the upper air.” The sentry unwittingly reveals to Dymer the specific beast he awaits was sired by Dymer in the palace in the woods. Dymer says he will face the beast alone, and the angelic sentry, impressed by his courage, gives Dymer his armour and weapons. The sentry reveals Dymer’s battle with the beast has been prophesied, but not the end of the battle. They wait, the beast comes, the fight begins, and Dymer dies; and the sentry sees the beast transformed into a majestic “wing’d and sworded shape” as the forest around them bursts intro greenery “as if from April showers[.]”

It’s a strange poem. It apparently lasts three days and nights, but while the poem is stated to open in April, the last mention of the forests blossoming “as if” from April rains suggests it actually ends in some other month. Dymer spends time mad or in vision, so that’s possible, but generally time seems to move oddly toward the end of the poem. The ending implies a kind of symbolic healing of the land, as a delayed spring finally arrives, but it’s difficult at first to see how that squares with Dymer’s initial act of rebellion in the Platonic city, with its apparent inspiration in the atmosphere of springtime (“Alas for laws and locks, reproach and praise / Who ever learned to censor the spring days?”). Perhaps we should see Dymer’s whole career leading toward his death, a final atonement or sacrifice to bring harmony back to the natural world.

Lewis observed in Surprised By Joy that the theme of a self-sacrificing god always resonated with him, and Dymer is an example of that image. The initial laugh and murder are the beginning of a series of errors that build to the point where the only resolution is Dymer’s death at the hands of his own offspring — an aspect of the story Lewis seemed to feel was particularly significant. From a certain point of view, then, Dymer could be a parodic version both of Adam, with the Platonic city an inverted Eden, and a Christ sacrificed in this case by his own son. Or perhaps the city’s an over-intellectual Valhalla; just as Wagner’s version of Valhalla was blighted from its founding by Alberich’s curse (Lewis, who loved Wagner’s operas, would later compare Dymer to Wagner’s Siegfried). That would all connect with the image of Balder invoked in the poem’s last stanza, though Dymer finds his final battle apart from the society that raised him, a personal Ragnarök. In either case, Dymer brings about a new kind of harmony by starting a train of events presumably leading to the destruction of the city, but the final fate of the city is actually left somewhat unclear. We don’t know if the city’s entirely destroyed, or merely divided against itself. In the same way Dymer’s counterpart, the rebel Bran, is left underdeveloped, his destiny unknown.

Lewis observed in Surprised By Joy that the theme of a self-sacrificing god always resonated with him, and Dymer is an example of that image. The initial laugh and murder are the beginning of a series of errors that build to the point where the only resolution is Dymer’s death at the hands of his own offspring — an aspect of the story Lewis seemed to feel was particularly significant. From a certain point of view, then, Dymer could be a parodic version both of Adam, with the Platonic city an inverted Eden, and a Christ sacrificed in this case by his own son. Or perhaps the city’s an over-intellectual Valhalla; just as Wagner’s version of Valhalla was blighted from its founding by Alberich’s curse (Lewis, who loved Wagner’s operas, would later compare Dymer to Wagner’s Siegfried). That would all connect with the image of Balder invoked in the poem’s last stanza, though Dymer finds his final battle apart from the society that raised him, a personal Ragnarök. In either case, Dymer brings about a new kind of harmony by starting a train of events presumably leading to the destruction of the city, but the final fate of the city is actually left somewhat unclear. We don’t know if the city’s entirely destroyed, or merely divided against itself. In the same way Dymer’s counterpart, the rebel Bran, is left underdeveloped, his destiny unknown.

The motion of the story’s clear, and the confluence of myth is remarkable. Obviously there are elements here of Oedipus. But Dymer’s experience in the mysterious palace perhaps also recalls Beowulf, struggling against Grendel’s mother with a worse result. By the end one might argue that Dymer’s a version of Launcelot, paying the ultimate place for a single night of sin. There is a strong sense of mythopoesis to the poem, the sense of a myth being created; but it’s not clear that Lewis knew what to do with his myth, or how to structure its telling.

The story seems to move through phases representing stages of Dymer’s life, which in turn seems to move more quickly than the passage of time the poem suggests. As I read it, Dymer seeks meaning, and is progressively disillusioned by various promising alternatives — sex, political rebellion, magic, dreams — before somehow coming terms with his life, and then moving beyond that life (the cemetery) to a final encounter with a divine force created or at least embodied by his own unwitting efforts. By the time this poem was published Lewis had begun to move away from strict atheism, having become a subjective idealist who believed that human beings were physical creatures with a higher self that could be identified with an Absolute; the Absolute produced the phenomenal world and the empirical self that is a part of the causal system of nature, but the free higher self could merge with it (I am here paraphrasing Owen Barfield’s explanation from his address “C.S. Lewis”). In the end, after his conversion to Christianity, Lewis came to feel that the Absolute was only another name for God. It is very tempting to read this poem as Lewis working through his idealism, trying to find a philosophical system acceptable to him, and moving toward full-fledged theism.

In fact Lewis wrote a preface to the poem for a 1950 reprinting, and much of that preface was concerned with situating that poem with respect to his personal history and his thought at the time he wrote it. Interestingly, he discusses some of it in terms of politics: “… I was already critical of my own anarchism. …It will be remembered that, when I wrote, the first horrors of the Russian Revolution were still fresh in every one’s mind; and in my own country, Ulster, we had had opportunities of observing the daemonic character of popular political ‘causes’.” One might recall the way politics had infiltrated his Boxen stories; but then Lewis would still be writing fiction directly concerned with contemporary politics after Dymer.

In fact Lewis wrote a preface to the poem for a 1950 reprinting, and much of that preface was concerned with situating that poem with respect to his personal history and his thought at the time he wrote it. Interestingly, he discusses some of it in terms of politics: “… I was already critical of my own anarchism. …It will be remembered that, when I wrote, the first horrors of the Russian Revolution were still fresh in every one’s mind; and in my own country, Ulster, we had had opportunities of observing the daemonic character of popular political ‘causes’.” One might recall the way politics had infiltrated his Boxen stories; but then Lewis would still be writing fiction directly concerned with contemporary politics after Dymer.

He also discusses a concept he calls the “Christiana Dream,” named for a character in Samuel Butler’s The Way of All Flesh, Christina Pontifex; in his diaries, Lewis uses the term “Christina Dream.” Either way, Lewis describes it as wish fulfilment, “the hidden enemy whom we were all determined to unmask and defeat.” Dreams, as he says elsewhere, that lead to the reverse of the virtues they celebrate; dreams of heroism that make the dreamer a coward, for example. (It is tempting to observe that at this time Lewis had a dream of being a strictly rational atheist, and within a few years became a Christian who argued that rationality was insufficient.) Dymer is in a sense about Dymer becoming progressively disillusioned. Psychologically, at least, Lewis felt the poem did something for him; in a diary entry in early 1927 he mentions hoping that another poem he was working on would clear up some philosophical difficulties “the way Dymer cleared up the Christina Dream business.” Writing the poem seems to have led him out of what he then regarded as mere wish-fulfilment, something distinct from and lesser than art.

And yet writing in 1950 he criticised his own assumptions in Dymer about what was wish-fulfilment and what was not. He felt that his dislike of occultism was overstated in the poem; and he felt that the depiction of Dymer’s temptation to fantasy, the strongest form of the wish-fulfilment dream, was a mistake. “Instead of repenting my idolatry,” he wrote, “I spat upon the images which only my own understanding greed had made into idols.” Broadly, what he means is that Dymer mocked a set of mythic images that meant much to Lewis, under the impression that they had to do with wish-fulfilment. Later, Lewis came to believe that he was wrong to mock them; that they had to do with a kind of romantic longing. Lewis called that emotion Sehnsucht, after a German term introduced to him by Owen Barfield (Barfield recalled using the word to object to Lewis’ championing of materialism). That longing, wrote Lewis, “is in itself the very reverse of wishful thinking: it is more like thoughtful wishing.” It was, effectively, joy. So Lewis came to believe that in attempting to reclaim joy by knocking down illusory dreams, he actually blocked off the true road back to joy.

Reading Lewis’ work of this time, particularly having also read Surprised by Joy, one sees him attempting to find joy and escape depression. Later he would see his conversion as, if not a resolution to his quest for joy, at least a realisation of what was really important; what the joy signified. But in Spirits in Bondage and Dymer that conclusion had not yet been reached. There’s a sense in which one sees Lewis testing everything he thought he valued, looking for some way to balance his instinct for myth and art with the concrete reality around him; a way to find meaning in the universe that he could accept intellectually.

Reading Lewis’ work of this time, particularly having also read Surprised by Joy, one sees him attempting to find joy and escape depression. Later he would see his conversion as, if not a resolution to his quest for joy, at least a realisation of what was really important; what the joy signified. But in Spirits in Bondage and Dymer that conclusion had not yet been reached. There’s a sense in which one sees Lewis testing everything he thought he valued, looking for some way to balance his instinct for myth and art with the concrete reality around him; a way to find meaning in the universe that he could accept intellectually.

It’s tempting to read that concern into work where it was perhaps not intended, or not in that way. Specifically, I can’t help but see it in a short story called “The Man Born Blind” which was collected by Walter Hooper in the volume The Dark Tower and Other Stories. One of the earliest surviving prose stories by the adult Lewis, it’s about a man, Robin, who was born blind but is cured by an operation, and how he tries to find and see “light.” Having been born blind, he can’t understand that light isn’t a thing to be looked at directly, but a thing by which one sees other things. He becomes obsessed by the idea of light. Finally he meets an artist on a clifftop who points to light he’s painting, fog glowing with sunlight at the base of the cliff — and Robin throws himself off the cliff into the light.

Hooper connects this story to an essay Lewis wrote in 1945, “Meditation in a Toolshed,” about the difference between looking along a thing rather than looking at it; certainly Lewis used the image of a beam of light there as well. For Lewis, the difference between the two ways of looking is that between a religious person taking part in a rite, and an anthropologist observing the ritual. For Lewis, the anthropologist looking at the ritual only gets a part of the truth. To understand the emotional content of a thing, to really understand its relevance to human character, it’s necessary to to see along it as the worshipper does. In “The Man Born Blind” the formerly blind man, Robin, doesn’t understand the distinction between the two kinds of looking. He doesn’t grasp the artist’s ability to look at light as both aesthetic revelation and technical object, but also doesn’t understand that one naturally looks along light at other things.

At the same time, the blind man’s final action comes about because he’s desperate to see light, which he’s come to invest with a spiritual significance. “If the operation has been a failure and I can’t see properly after all, tell me,” he begs his wife Mary. “If there’s no such thing — if it was all a fairy tale from the beginning — tell me.” Later, he looks for light “searching with a hunger that had already something of desperation in it.” He relaxes by closing his eyes and living again as one blind. And he comes to doubt the existence of light: “What one heard among them [the sighted] was merely the parrot-like repetition of a rumour — the rumour of something which perhaps (it was his last hope) great poets and prophets of old had really known and seen.”

At the same time, the blind man’s final action comes about because he’s desperate to see light, which he’s come to invest with a spiritual significance. “If the operation has been a failure and I can’t see properly after all, tell me,” he begs his wife Mary. “If there’s no such thing — if it was all a fairy tale from the beginning — tell me.” Later, he looks for light “searching with a hunger that had already something of desperation in it.” He relaxes by closing his eyes and living again as one blind. And he comes to doubt the existence of light: “What one heard among them [the sighted] was merely the parrot-like repetition of a rumour — the rumour of something which perhaps (it was his last hope) great poets and prophets of old had really known and seen.”

In retrospect, it looks like Lewis was using light here as a symbol for God. And yet at the time the story was probably written he wasn’t a theist. I think light in this context is actually a symbol for something that came to be linked with theism for Lewis: the emotion he called “joy” or Sehnsucht. Lewis eventually came to feel that this joy wasn’t a joy in itself, but the feeling of desire for something else; for God. As I read the story, Lewis is talking about the experience of joy, the sudden transport that came to him in reading a certain kind of poem or experiencing the natural world. Others around him spoke of joy, but couldn’t explain it in a way that helped him to recover it. So the story’s about looking along joy rather than at it. Lewis has elsewhere recorded how he tried to recapture the sense of joy by copying the external actions that seemed to give rise to the emotion at a given point. These attempts didn’t work, because (I think he would say) he was trying to look at joy, at its externals. And failing even at that, because in the end he learned nothing about joy itself. Joy, like light, is something that one almost always has to look along. And, if great art depicting joy makes us yearn for it, that yearning is misguided; joy itself is merely a yearning for something greater (and thus the artist unintentionally brings about the formerly blind man’s destruction).

In March of 1924 Lewis had read Samuel Alexander’s book Space, Time, and Deity, which distinguished between the thing that is perceived and the act of perception; as Lewis would later explain it to his class, the distinction between contemplation and enjoyment. He records in his diary that in a class discussion one of his students “was specially good, saying … ‘It is as if, not content with seeing with your eyes, you wanted to take them out and look at them — and then they wouldn’t be eyes.’” So here again is the distinction between looking at and along. Lewis came to feel that his error in seeking joy, as he wrote in Surprised by Joy, was “to contemplate the enjoyed.” In fact, he concludes in that book, joy “was valuable only as a pointer to something other and outer.” Robin in “The Man Born Blind” never comes to understand that light is only a pointer; and so, following art for its own sake, he throws himself over a cliff.

In March of 1924 Lewis had read Samuel Alexander’s book Space, Time, and Deity, which distinguished between the thing that is perceived and the act of perception; as Lewis would later explain it to his class, the distinction between contemplation and enjoyment. He records in his diary that in a class discussion one of his students “was specially good, saying … ‘It is as if, not content with seeing with your eyes, you wanted to take them out and look at them — and then they wouldn’t be eyes.’” So here again is the distinction between looking at and along. Lewis came to feel that his error in seeking joy, as he wrote in Surprised by Joy, was “to contemplate the enjoyed.” In fact, he concludes in that book, joy “was valuable only as a pointer to something other and outer.” Robin in “The Man Born Blind” never comes to understand that light is only a pointer; and so, following art for its own sake, he throws himself over a cliff.

Lewis would ultimately resolve his search for joy by deciding that what he was looking at when he experienced joy was God. His early poems, and “The Man Born Blind,” are records of the search, and strike me as interesting because they’re records made along the way and not in retrospect. But if Lewis’ emotional life makes for interesting consideration, his art is not yet at its most interesting on its own terms, purely as stories. That would come soon enough, I feel, as he began writing longer tales in prose; the first of which I will look at next Sunday.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy a collection of his essays for Black Gate, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] LEWIS PART THREE. Matthew David Surridge unveiled “Wandering the Worlds of C.S. Lewis, Part III: Dymer” at Black […]

Just a thought. Reading your summaries of both poem and story, I kept thinking of Lindsay’s A Voyage to Arcturus. Maskull’s journey and search for some kind of enlightenment echoes Dymer’s journey. Robin’s obsession with light echoes the strange light of the planet, with its different primary colours. Maskull, at one point, is transformed and given many eyes. Then the comment of that student. I don’t know when Lewis first read Arcturus but these pieces do seem to show Lindsay’s influence.

That’s a good point. A Voyage to Arcturus was a definite influence on Lewis’ Space Trilogy. But according to the link here —

http://www.discovery.org/a/882

— Lewis didn’t read it until 1936. Still, if he was already thinking along the lines of what he found in the book, that would help explain why he connected with it so much.

Thanks for the link. Seems like coincidence or correspondence, rather than influence. Perhaps there was something in the air that led both authors to use similar tropes/devices.