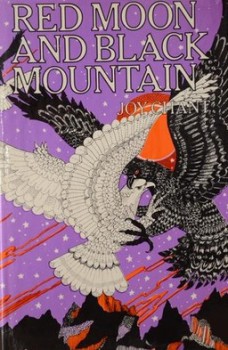

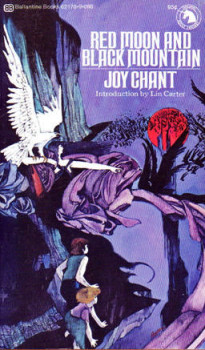

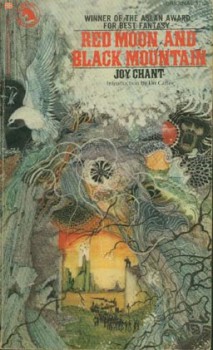

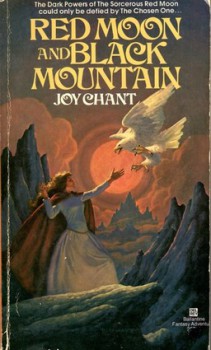

Red Moon and Black Mountain by Joy Chant

Joy Chant’s first novel, Red Moon and Black Mountain (1970), was published when she was only twenty-five years old. In the afterword to a later novel she explains how the world of her stories, Vandarei, grew out of fantasies she made up for herself as a child. At one point she made herself the great and majestic Queen of this world. The story of three siblings — Oliver, Penelope, and Nicholas — pulled out of England into the land of Vandarei, it reads a little like the Chronicles of Narnia crossed with The Lord of the Rings and wrung through Alan Garner’s darker fantasies.

Joy Chant’s first novel, Red Moon and Black Mountain (1970), was published when she was only twenty-five years old. In the afterword to a later novel she explains how the world of her stories, Vandarei, grew out of fantasies she made up for herself as a child. At one point she made herself the great and majestic Queen of this world. The story of three siblings — Oliver, Penelope, and Nicholas — pulled out of England into the land of Vandarei, it reads a little like the Chronicles of Narnia crossed with The Lord of the Rings and wrung through Alan Garner’s darker fantasies.

The novel has often been dismissed as a mere clone of Tolkien’s work — most recently right here at Black Gate by Brian Murphy — but RMBM is a book that has also received tremendous praise over the decades. In his introduction to the first American edition, published as part of his Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, Lin Carter refers to it as a masterpiece. James Stoddard, author of The High House, calls it the best fantasy novel no one reads. It was the second recipient of the Mythopoeic Award back in 1972.

I first read RMBM about fifteen years ago, but retained only the dimmest memories of it. Rereading it, I will say it is one of the best works of epic high fantasy I’ve ever read. While not the toil of a lifetime, Chant draws on the same deep body of European mythology and archetypal characters as Tolkien with similar power and effect. Maybe due to its roots in her childhood imagination and definitely out of a deep well of talent, in Vanderei, its people, and its legends, Chant created a deeply heartfelt and fantastic world.

A mysterious figure lurking along the garden path sends the children out of this world and into Vandarei out of grave necessity. Penelope and Nicholas materialize along a path trod by the grave and steely princess In’serinna and her retinue. Oliver arrives among the nomadic Khentors and their single-horned horses. All the children have a part to play in an upcoming struggle for the future of Vandarei. Oliver, especially, will find himself tested to his limits.

In ages past a king and sorcerer, Fendarl, became afraid of death and so succumbed to the temptation of the darkest magics. He was discovered and eventually driven from Vandarei but not destroyed. Now he has recouped his power and is ready to test the bans that hold him back. From atop the Black Mountain where Fendarl once ruled his kingdom, and under the Red Moon of malign sorcery, in one of the first haunting scenes in the novel Penelope and Nicholas witness one of his efforts when he sends his host of black eagles to break through the barriers:

One by one the other black eagles flew up, and then the children saw how many there were: at least three hundred, gathering in a black cloud above them. They were far larger, too, than the white eagles. Looking up, Nicholas saw the Princess’s face was whiter than before; and the men looked as grieved as they were grim.

The last black eagle joined the flock. For a moment there was utter silence. Then with a scream of hate and defiance the King of the White Eagles leapt from the crag upwards at his enemies; and all his people followed.

The Black Eagle answered with a harsh cry, and dropped toward the other, and the black birds followed in a swarm. Then began the Battle of the Eagles, to see which the Princess In’serinna had journeyed many miles, and two children been brought out of another world.

As you can see, Chant employs a bit of the olde timey prose. It’s a rare writer that can pull that off successfully, and she does. Like Stephen Donaldson in Lord Foul’s Bane (reviewed here just last week), her goal is not just to tell a story, but also to create images that feel plucked from forgotten legends. The prose distances the action, creating an aura of a great tale recounted many generations later. Too often this sort of high diction just comes off unintentionally comical. There are times she lays it on a little too thick, but overall Chant does it just right.

As you can see, Chant employs a bit of the olde timey prose. It’s a rare writer that can pull that off successfully, and she does. Like Stephen Donaldson in Lord Foul’s Bane (reviewed here just last week), her goal is not just to tell a story, but also to create images that feel plucked from forgotten legends. The prose distances the action, creating an aura of a great tale recounted many generations later. Too often this sort of high diction just comes off unintentionally comical. There are times she lays it on a little too thick, but overall Chant does it just right.

While his siblings are watching the Battle of the Eagles, Oliver is already undergoing a transformation into Li’vanh the Khentor warrior. The portents attached to his arrival lead the Khentor to believe he is a great champion sent to them for some yet unknown purpose. Oliver easily slips into his new role, even forgetting the details of his past.

For Oliver time passes more quickly, so when he finally meets Nicholas and Penelope again he has aged much more and grown into a young man. They are overjoyed to see him but he barely recognizes them:

Remembrance was agony.

He looked at his brother and sister with the eyes of a stranger. These fair foreign children in their Harani clothes were alien to him; he could not follow the strange accent of their quick, easy speech. And yet those faces, those voices, were cruelly familiar, painfully dear. Their kinship laid hold on him and would not be denied, shaming his forgetfulness, waking every moment more echoes of a world to which he no longer belonged.

While much of RMBM is concerned with the planning of battles, the description of ruins and cities, and scenes of great beauty and strangeness, Oliver’s story is something different. While Penelope’s and Nicholas’s adventures take the reader across Vandarei and tell its history, Oliver’s story is more personal and poignant. When the reason he has been brought to Vandarei — why he has been trained to be a warrior — is revealed, while not surprising in the least, it is still disturbing.

While much of RMBM is concerned with the planning of battles, the description of ruins and cities, and scenes of great beauty and strangeness, Oliver’s story is something different. While Penelope’s and Nicholas’s adventures take the reader across Vandarei and tell its history, Oliver’s story is more personal and poignant. When the reason he has been brought to Vandarei — why he has been trained to be a warrior — is revealed, while not surprising in the least, it is still disturbing.

Despite believing he is fully prepared for the trials he must face, when the time comes Oliver ends up wounded deep in his soul. The final chapters of the book take on a darker tone. Victory extracts a price he is neither expecting nor ready for. While Penelope and Nicholas are able to look on their time in Vandarei almost wistfully, Oliver is forever changed and marked. When he laments his lost innocence he is answered:

‘And have men sunk so far, that the best they can hope for is innocence? Do they no longer strive for virtue? For virtue lies not in ignorance of evil, but in resistance to it.’

Oliver bowed his head. “And what have I gained?’ he asked.

‘What does the silver gain in the fire, and the iron in the forging?’

While RMBM begins as a children’s book it ends up in some very adult territory.

The chapters with Penelope and Nicholas provide Chant the opportunity to put Vandarei on display. Captured, In’serinna and Penelope are brought to Castle Lamentation. Unable to voice the grief he felt when his wife died, its builder covered the walls with “funnels, horns, stone pipes turned all way” so it would always weep in the wind. Great flocks of swans darken the skies in flight from Fendarl’s marshalling forces. Staying in the woods with the faery-like Nihaimurh Nicholas falls asleep, missing “the chance of going where no mortal had ever been.” These episodes and others are written with a beauty and mystery I don’t find in most of today’s fantasy novels.

The chapters with Penelope and Nicholas provide Chant the opportunity to put Vandarei on display. Captured, In’serinna and Penelope are brought to Castle Lamentation. Unable to voice the grief he felt when his wife died, its builder covered the walls with “funnels, horns, stone pipes turned all way” so it would always weep in the wind. Great flocks of swans darken the skies in flight from Fendarl’s marshalling forces. Staying in the woods with the faery-like Nihaimurh Nicholas falls asleep, missing “the chance of going where no mortal had ever been.” These episodes and others are written with a beauty and mystery I don’t find in most of today’s fantasy novels.

This novel is not without its flaws. Several characters enter the story, present an interesting face to the reader, only to vanish with nary a mention again. Aside from Oliver and the Princess In’serinna, few of the characters rise above archetypes. For me — and for the type of story Chant’s telling — that’s quite alright, but for many readers that could be a drawback. For those who enjoy detailed descriptions of every meal and item of clothing, this book might feel insubstantial.

Epic high fantasy needn’t be epic in length. What matters is the story: creation — or at least the world — is at stake, the outcome will be settled between the forces of good and evil, and the tale is told from multiple viewpoints. Red Moon and Black Mountain shows how it can be done in under three hundred pages.

Chant wrote two more novels and a short story set on Vandarei: The Grey Mane of Morning, When Voiha Awakes, and “The Coming of the Starborn.” None are in print. She wrote only one more novel, the Arthurian tale The High Kings in 1983, and then fell silent.

Fletcher Vredenburgh reviews here at Black Gate most Tuesday mornings and at his own site, Swords & Sorcery: A Blog when his muse hits him. You can read his thoughts about epic high fantasy here.

“Best fantasy novel no one reads.” Yep, that sounds about right to me.

One of these days I need to read her other novels.

Ok, ok – you’ve convinced me! The copy that I’ve had for decades (and have…never…read) get dusted off before the new year.

I read this story over thirty years. Only one character and one scene sticks in my mind. Oliver is the character. I thought this part of the book was really well done. The scene? As far as I can remember a girl in the tribe is into him and Oliver blows her off. Something about being under a wagon?

@Joe H – I’m really surprised it’s not available in at least as a cheap e-book

@Thomas – let me know what you think

@Aonghus – Pretty good recall. My review sorely neglects the detail and care she devoted to the creation of the Khentor. She obviously loved them as her next book was about them.