The Charge of the Light Brigade at the Battle of Balaklava, October 25, 1854, Part II of II

Read Part I here.

The Charge of the Light Brigade

There were four speeds for the cavalry:

Walk: not to exceed four miles per hour

Trot: not to exceed eight and a half miles per hour

Gallop: eleven miles per hour

Charge: not to exceed the utmost speed of the slowest horse

The Light Brigade started at a walk because the horses could not maintain the charge speed for over a mile. When the first line was well clear of the second, Cardigan ordered “Trot.” The more experienced men knew at that speed it would take them about seven minutes to reach the battery. As they trotted down the valley, ten Russian guns could reach them.

Captain Nolan who should have gone back to Raglan’s headquarters rode in front of the Light Brigade. He was the first one killed and his horse carried him back among the attacking men.

I saw the shell explode of which a fragment struck him. From his raised sword-hand dropped the sword. The arm remained upraised and rigid, but all the other limbs so curled in on the contorted trunk as by a spasm, that we wondered how for the moment the huddled form kept the saddle. The weird shriek and the awful face haunt me now to this day, the first horror of that ride of horrors.

— Private James Wightman, 17th Lancers

One possible explanation for Captain Nolan’s ride across the front of the Brigade is he was trying to redirect the Light Brigade to attack the guns on the Causeway Heights to their right.

As they started down the valley, many of them had no hope of survival.

A child might have seen the trap that was laid for us, every private dragoon did.

— Captain Thomas Hutton, 4th Light Dragoons

Cardigan knew it too but he was determined to set an example. He led at a trot and was determined to hold that pace until only 250 yards from the enemy. The men hoped he would quicken the pace but this trot was according to military regulations.

The Russian view:

…a battery of the 16thArtillery Brigade had positioned its ten guns to fire into the flank of any British force foolhardy enough to advance on Russian forces. For forty minutes the British light cavalry had stood at the entrance to the valley, about 1,000 yards away and just within range of the 12-pounder guns, but there was no question of opening fire while they presented no threat. Immediately they moved into the valley the order was given, the gun teams went into action and in less than a minute the men stood back ready. The British advanced at a trot as if unconcerned. The guns boomed and leapt, and battery officers peered through the powder to see what damage had been done.

Lord Raglan expected the Light Brigade to advance a short distance along the valley before turning to its right and climbing the slopes of the Causeway Heights towards the guns in the redoubts. Instead of turning, Cardigan was continuing straight on towards the Don Cossack guns at the far end of the valley – a long ride that would bring his regiments under intense and sustained artillery fire.

Crimean War Russian Artillery Battery (photo Pinterest website)

As shells opened gaps in the line, the men closed up to maintain a solid, compact line that would hit the enemy with a devastating shock. The officers were more intent on setting a good example, and if they shouted out at all, it was to urge the survivors forward. Lieutenant Percy Smith of the 13th Light Dragoons was disabled, his right hand left useless by a shooting accident, and although he normally wore an iron arm-guard he had mislaid it that morning and rode without it, controlling his horse with his left hand. He carried neither pistol nor saber, yet rode on anyway, calling out to the men behind and cursing the enemy.

Testimony of British Lancers:

At that moment I felt my blood thicken and crawl, as if my heart grew still like a lump of stone within me. I was for a moment paralyzed, but then with the snorting of the horse, the wild gallop, the sight of the Russians become more distinct, and the first horrible discharge with its still more horrible effects, my heart began to warm, to become hot, to dance again, and I had neither fear nor pity! I longed to be at the guns. I’m sure I set my teeth together as if I could have bitten a piece out of one. Anonymous, 8th Hussars

This following statement from Corporal Thomas Morley contradicts the exact amount of guns in the Don Cossacks battery at the other end of the valley — a number which has been in dispute. The Russians insist it was eight.

The Russian gunners were well drilled. There was none of that crackling sound I have often heard, where one gun goes off a little ahead and the others follow, having the effect of a bunch of fire-crackers popping in quick succession. In such cases the smoke of the first gun obscures the aim of the rest…There were probably twenty cannon at our right firing at us and two batteries – twelve guns – in front. If we had been moving over uneven ground we should have had some slight protection in the necessary uncertainty of the aim of the guns, but moving as we did in compact bodies on smooth ground directly in range, the gunners had an admirable target and every volley came with terrible effect.

— Corporal Thomas Morley, 17th Lancers

And there is the tongue-in-cheek report from the following trooper.

It was about this time that Sergeant Talbot had his head clean carried off by a round shot, yet for about thirty yards further the head-less body kept the saddle. My narrative may seem barren of incidents, but amid the crash of shells and the whistle of bullets, the cheers and the dying cries of comrades, the sense of personal danger, the pain of wounds and the consuming passion to reach an enemy, he must be an exceptional man who is cool enough and curious enough to be looking serenely about him for what painters call “local color.” I had a good deal of “local color” myself, but it was running down the leg of my overalls from my wounded knee.

— Private James Wightman, 17th Lancers

As the second line moved on, the Heavy Brigade prepared itself to follow. As he gave the signal to begin the charge, Lucan and his men had no greater hopes of surviving this ride than their fellows among the Light Brigade.

In a few moments we were in the hottest fire that was probably ever witnessed. The Regiments were beautifully steady. I never had a better line in a Field Day, the only swerving was to let through the ranks the wounded and dead men and horses of the Light Brigade, which were even then thickly scattered over the plain. It was a fearful sight, and the appearance of all who retired was if they had passed through a heavy shower of blood, positively dripping and saturated, and shattered arms blowing back like empty sleeves, as the poor fellows ran to the rear. Another moment and my horse was shot on the right flank. A few fatal paces further, and my left leg was shattered.

— Lieutenant Colonel John Yorke, 1st (Royal) Dragoons

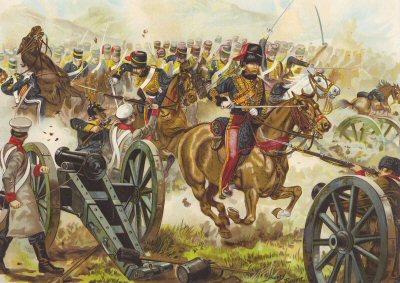

French Chasseurs D’Afrique attack (photo British Battles website)

Fourth Charge: the French Cavalry

The Heavy Brigade would have suffered even more severely if not for the fourth charge of the day by the French cavalry Chasseurs d’Afrique. When their major saw the attack on the Light Brigade from the Fedioukine Heights, he led his men and charged the Russian guns. The Russians were forced to flee.

Controversially, Lucan decided to turn the Heavy Brigade back. The men of the Heavy Brigade were scandalized by this move.

For these cavalrymen the one prospect worse than advancing into the fire ahead was turning back and deserting their comrades in the Light Brigade. In retiring the Heavies Lucan left the Light Brigade without the support Cardigan and his regiments assumed was coming up behind them.

At the moment he decided to turn back, Lucan turned to Lord William Paulet and said, “They have sacrificed the Light Brigade. They shall not have the Heavy, if I can help it.

The first line of the light brigade had now traveled almost halfway down the valley and entered the range of the battery to their front. Further back, Lord George Paget was having difficulty keeping the two regiments of the second line together.

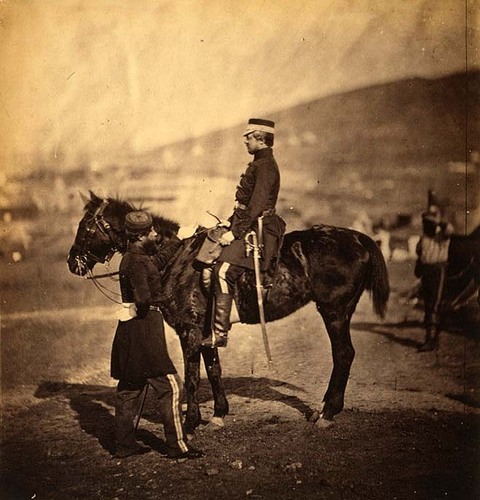

Brigadier General Lord George Paget C.B. (photo Old Pictures website)

Every man felt convinced that the quicker he rode, the better chance he would have of escaping unhurt.

— Cornet George Wombwell, 17th Lancers

As more men fell, the number of riderless mounts increased. Although they are considered a boon to a soldier who lost his own horse, they can also be a threat on a field of fire.

I was of course riding by myself and clear of the line and for that reason was a marked object for the poor dumb brutes, who were by this time galloping about in numbers like mad wild beasts. They consequently made dashes at me, some advancing with me a considerable distance, at one time as many as five on my right and two on my left, cringing in on me, and positively squeezing me, as the round shot came bounding by them, tearing up the earth under their noses, my overalls being a mass of blood from their gory flanks (they nearly upset me several times, and I had to use my sword to rid myself of them). I remarked their eyes, betokening as keen a sense of the perils around them as we human beings experienced…

— Lord George Paget, 4th Light Dragoons

“Jaws of Death” (photo Scriblets-Bleets website)

The Russian View:

As they worked frantically, some among the gun crews now doubted their ability to stop the enemy cavalry. They could see there were lancers in the front line and even as they watched these men lowered their poles – the red and white pennons fluttering madly at the tips were clearly visible. That meant the charge had been called; the horses would be spurred to their utmost and the enemy would be among the guns within seconds. As the gunners stood back ready, panic gripped them. When the guns thundered for the final time, the bravest drew their sabers, though many another dived beneath the gun carriages, not so much seeking shelter from the hooves of any horses that might reach the gun line as safety from the steel tips of any lances that came with them. Only a few of the youngest men turned to run, offering their backs to the lancers and inviting the point.

Charge of the Light Brigade from Russian positions on the Fedioukine Hills

(photo British Battles website)

My first thought after we were through the line was to look for an officer to see what we were to do. I saw Lord Cardigan at first but I had no impulse to join him. I think no British soldier ever had. He led 670 and none rallied on him. I saw troopers riding past him to the right and left. He was about 50 yards beyond the guns on their extreme left.

— Corporal Thomas Morley, 7th Lancers

After this sighting, Cardigan disappeared – he moved back towards the guns where the smoke was still dense and from that moment gave no orders and played no further part in the action. Some among both the officers and the men believed that he deserted his brigade at the guns and retired early. However, there is testimony from some of the men in the Brigade that he did not leave the field.

Cardigan did not pursue the Russian cavalry and did not seek to re-form groups of men. There is no suggestion that his actions were due to cowardice or loss of nerve, but they did demonstrate his inadequacy as a senior officer. His orders were to attack the Russian battery and he did exactly that but no more. Cardigan’s declaration that no more should have been expected of him is not an acceptable excuse from the lips of a brigade commander.

To the survivors of the Light Brigade the 200 men who made up the eight gun crews were responsible for the terrible carnage inflicted on their fallen comrades and now they took a terrible revenge.

Russian Cossack sits by his dead horse (photo British Battles website)

Captain Morris, 17th Lancers, made for an officer he took to be the Russian commander charging with his saber arm held straight out and the point of his blade targeting the chest; it slid in up to the hilt so that half of its length protruded from the man’s back. The blade locked in muscle and bone, and as the body slumped back in the saddle Morris was almost pulled from his horse. While struggling to withdraw his saber, two of the enemy closed on him. He was hit by the swing of a blade above the left ear and a second blow came down across his skull. As he fell his saber came free. Morris was one of the most experienced cavalry officers on the field and admitted later that he did not know how he came to use the thrust in preference to the cut, but vowed never to do so again.

Behind the guns, many of the Light Brigade continued to pursue the Russian cavalry who chose to flee in spite of their vast numbers, expecting that the Heavy Brigade would be following this attack momentarily. The surviving Light Brigade officers also expected the arrival of the Heavy Brigade. They never came. The Russians regrouped and deployed to attack the British as they returned up the valley.

The Russian view:

Everyone thought that there was only one way out of the valley for the English – they had no choice now but to surrender. We watched for them to lay down their sabers and lances. But that is not what happened. The English chose to do what we had not considered because no one imagined it possible – they chose to charge our cavalry once again, this time heading back along the same ground. These mad cavalrymen were intent on doing what no one thought could be done.

— Lieutenant Stefan Kozhukhov

Helter-skelter then we went at these lancers as fast as our poor tired horses could carry us. As we approached them I remarked the regular manner in which they executed the movement of throwing their right half back, thus seemingly taking up a position that would enable them to charge down obliquely upon our right flank as we passed them.

— Lord George Paget, 4th Light Dragoons

Paget and his men rushed on expecting to be taken on their right flank and knowing they had no defense from the long reach of the lances. The Russians advanced within a few yards of them and inexplicably stopped. Lord George Paget could not understand their actions and commented, “Had that force been composed of English ladies, I don’t think one of us could have escaped.”

The survivors broke through the Russian cavalry but their ordeal was far from over. All were one mile from safety and many of the men and horses were exhausted, wounded or both. There were Cossacks at their backs and the enemy artillery was waiting to have a second go at them as they crossed their muzzles on the way back.

I was attacked by Russian cavalry through whom I cut my way, my more than ordinary height combined with a powerful frame proving most advantageous to me. I had no sooner got clear than I was knocked down and ridden over by riderless horses.

— Corporal James Nunnerley, 17th Lancers

Three riderless horses were wandering up the valley a little distance from each other. The first, seeing me and knowing the uniform, halted close to me. On looking round him, I found he was badly wounded, the blood flowing in several places, so I gave him a pat and said “Go on, poor fellow.” The second then came up, he too was wounded, so I said “Go on.” When the third came, I found on looking round him that he was not wounded so I mounted and rode on.

— Troop Sergeant Major George Smith, 11th Hussars

Aftermath of the Charge of the Light Brigade

(Painting by Elizabeth Thompson, Lady Butler 1876 Balaclava)

A ride of a mile or more was before us, every step of which was to bring us more under the fire from the heights. And what a scene of havoc was this last mile strewn with the dead and dying, and all friends, some running, some limping and some crawling! Horses in every position of agony, struggling to get up, then floundering again on their mutilated riders!

— Lord George Paget, 4th Light Dragoons

This account sounds as if it came straight out of a Robert E. Howard Breckenridge Elkins’ tale:

My horse was shot dead, riddled with bullets. One bullet struck me on the forehead, another passed through the top of my shoulder. While struggling out from under my dead horse a Cossack standing over me stabbed me with his lance once in the neck near the jugular, again above the collar bone, several times in the back, and once under the short rib; and when, having regained my feet, I was trying to draw my sword, he sent his lance through the palm of my hand. I believe he would have succeeded in killing me, clumsy as he was, if I had not blinded him for the moment with a handful of sand.

— Private James Wightman, 17th Lancers

Heroism was the order of the day. Wightman and several others were taken prisoner and marched away with the butts of Cossack lances prodding them from behind. Wightman found himself beside Private Thomas Fletcher of the 4th Light Dragoons.

With my shattered knee and the other bullet wound on the shin of the same leg, I could barely limp, and good old Fletcher said, “Get on my back, chum!” I did so, and then found that he had been shot through the back of the head. When I told him of this, his only answer was “Oh, never mind that, it’s not much, I don’t think.” But it was that much that he died of the wound a few days later; and here he was, a doomed man himself, making light of a mortal wound, and carrying a chance comrade of another regiment on his back. I can write this, but I could not tell of it in speech, because I know I should play the woman.

— Private James Wightman, 17th Lancers

The Russian view:

The survivors of the Light Brigade were pursued up the valley by Hussars and Cossacks and many British cavalry were cut down. Some of the Russians were killed by their own artillery firing indiscriminately from the Causeway Heights.

All of the mounted survivors had by now reached the British lines. The Heavy Brigade regiments cheered as they came in.

Well, there is an end to all things, and at last we got home, the shouts of welcome that greeted every fresh officer or group as they came struggling up the incline, telling us of our safety.

— Lord George Paget, 4th Light Dragoons

I found that I could not dismount from the wound in my right leg and so was lifted off, and then how I caressed the noble horse that brought me safely out.

— Private William Pennington, 11th Hussars

The Survivors of the Charge of the Light Brigade

Light Brigade Roll Call After Battle of Balaklava (photo British Battles website)

The survivors re-formed on approximately the position from which the Light Brigade set forth. The first roll was called, not to establish how many survived but to discover how many were still mounted and fit for duty, lest they be required for further action that day.

The whole affair, from the moment we moved off until we re-formed on the ground from which we started, did not occupy more than 20 minutes. On the troops forming up, I had them counted by my Brigade-Major and found there were 195 mounted men out of about 670.

— Lord Cardigan

Brighton states that “Once back, the men experienced a curious mixture of elation and anger. They felt that they had done everything asked of them and much more besides, yet so many of their comrades had been left behind in the valley. It would be later that severe questions were asked about why the charge was ordered; on the afternoon and evening of that day what the survivors of the Light Brigade most wanted to know was why the Heavy Brigade had not come up to support them at the guns.”

And who, I ask, was answerable for all this? The same man who ordered Lord Cardigan to charge with 670 men an army in position and then left them to their fate – it was not unlike leaving the forlorn hope, after storming a town, to fight their own way out again, instead of pushing on the supports. We cut their army completely in two, taking their principal battery, driving their cavalry far to the rear. What more could 670 men do?

— Troop Sergeant Major George Smith, 11th Hussars

The Aftermath

At 11:10 a.m., on October 25, 1854, the almost seven hundred men of the Light Brigade began their advance through “the valley of death.” Their bravery in the face of the enemy and death itself fired up the British public. England’s poet laureate was inspired to write “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Children memorized it in school. But the Light Brigade’s twenty minute ride into almost certain death was the result of blunders made by their officers and “who killed the Light Brigade” was now the question that needed to be answered.

It took three weeks for the dispatches relating to the Light Brigade charge to get back to England. The newspaper account, written by William Howard Russell, the Crimean war correspondent for The Times appeared on November 14, 1854. Shortly after reading it, Poet Laureate, Alfred, Lord Tennyson wrote the poem “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Its first publication was in The Examiner on December 9, 1854.

Alfred Lord Tennyson Poet Laureate (photo Victorian Web)

The Charge Of The Light Brigade

by Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Memorializing Events in the Battle of Balaclava, October 25, 1854

Half a league half a league,

Half a league onward,

All in the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred:

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!

Charge for the guns’ he said:

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

‘Forward, the Light Brigade!’

Was there a man dismay’d ?

Not tho’ the soldier knew

Some one had blunder’d:

Theirs not to make reply,

Theirs not to reason why,

Theirs but to do & die,

Into the valley of Death

Rode the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon in front of them

Volley’d & thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

Boldly they rode and well,

Into the jaws of Death,

Into the mouth of Hell

Rode the six hundred.

Flash’d all their sabres bare,

Flash’d as they turn’d in air

Sabring the gunners there,

Charging an army while

All the world wonder’d:

Plunged in the battery-smoke

Right thro’ the line they broke;

Cossack & Russian

Reel’d from the sabre-stroke,

Shatter’d & sunder’d.

Then they rode back, but not

Not the six hundred.

Cannon to right of them,

Cannon to left of them,

Cannon behind them

Volley’d and thunder’d;

Storm’d at with shot and shell,

While horse & hero fell,

They that had fought so well

Came thro’ the jaws of Death,

Back from the mouth of Hell,

All that was left of them,

Left of six hundred.

When can their glory fade?

O the wild charge they made!

All the world wonder’d.

Honour the charge they made!

Honour the Light Brigade,

Noble six hundred!

The Charge of the Light Brigade was not the wildness of drunks or lunatics, but of men who, while held in check by both Lord Cardigan and their own discipline, had at the same time passed beyond orders that made sense, and perhaps beyond sense itself. The magnificence was in the display of this will to charge that set men free from fear of the enemy, the guns and even death itself.

Placing the Blame

The generally accepted total number of officers and men who took part in the charge is 664. However, Terry Brighton sets that number at 666.

| Killed outright or died of their wounds | 110 |

| Wounded and returned to lines | 129 |

| Wounded and taken prisoner | 32 |

| Total killed and wounded | 271 |

The number of horses killed is considerably higher. Lord Paget recorded 332 horses killed in the charge and a further 43 were shot for their wounds upon their return to the lines.

Because of the errors in judgment made by officers, 271 men were killed or wounded and 375 horses were lost. The search began to find the person or persons responsible. Historical accounts narrowed it down to four men: Lord Raglan, who gave the order orally to General Airey, who then wrote it down; Captain Nolan, who delivered the order to Lucan; Lord Lucan, in command of the Cavalry Division, who passed on the order orally to Cardigan; Lord Cardigan, in command of the Light Brigade, who led the charge.

Each of the surviving officers blamed one another both up and down the chain of command. Instead of examining the mistakes that each made, Lord George Paget suggested an examination should be conducted to reveal who could have identified the wrong and then failed to act on it:

Who lost the Light Brigade? It was determined that three officers contributed to a series of fundamental errors.

But if we ask (with Paget) which of them could by virtue of his rank and position have the ability to perceive and prevent the terrible direction those errors were taking, that officer can only be Lord Lucan.

Apparently the official inquiry agreed.

The Duke of Newcastle wrote to Raglan on January 27th, 1855: Inform Lord Lucan that he should resign command of the Cavalry Division and return to England.” The official reason was the relationship between Raglan and Lucan had broken down and therefore Lucan could not properly carry out his duties. There was more to it than that as The Times of March 9 expressed in its verdict on Lord Lucan. “It is not fitting that officers so little gifted with the powers of understanding or executing orders should be entrusted with the lives of men or the honor of nations.”

Lord Cardigan was absolved of all blame.

We can conclude that Lord Cardigan has no case to answer, and that the fault for the loss of the Light Brigade must be shared between their lordships Raglan and Lucan and Captain Nolan – but the greatest part of it lies with Lord Lucan.

Evaluating the Success of the Charge

Whether the Charge of the Light Brigade is considered a success or defeat is determined by the criteria used. If it is judged in terms of the intended objective of the original order from Lord Raglan, it was a failure. The Light Brigade did not prevent the Russians from carrying away the guns at the Heights. If it is looked at it from the objective of taking the guns to the front of them, it was an astounding success.

The Plight of the Light Brigade Veterans

The suffering of the Light Brigade veterans did not end on October 25, 1854. While the nation’s schoolchildren learned to “honor the charge they made” by rote, a public appeal for funds to assist the veterans raised a mere twenty-four pounds. When he returned from serving in the American Civil War [according to The Daily Mail.com 11/18/2010 tens of thousands of British soldiers fought with both the Confederate and Union forces] Private John Richardson, 11th Hussars, could not find any work and ended up in a Cheetham workhouse, a poorhouse in which the able residents had to work. Other veterans of the Charge were also experiencing the same plight. When interviewed by Spy a popular penny newspaper, Richardson stated that Lord Cardigan made a promise to the survivors of the charge concerning the future. “He said it was certain that every man who rode in the Charge would be provided for.”

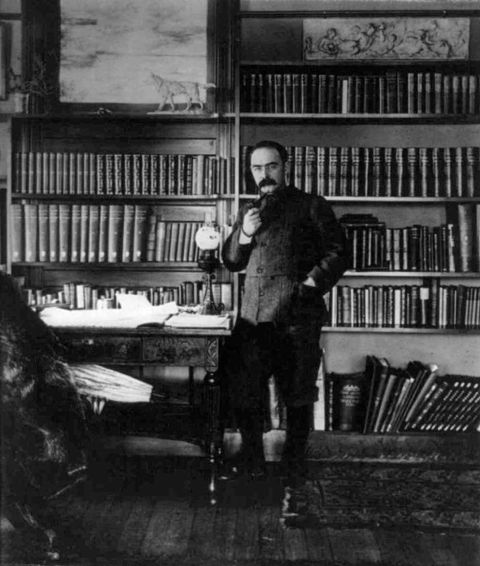

In his poem, “The Last of the Light Brigade,” Kipling imagines these impoverished veterans of the Light Brigade Charge visiting Tennyson with a request that he complete his story by telling all England of their present state. Kipling’s words on behalf of these last twenty men of the Brigade are as sharp and painful as the knives and swords these men wielded on October 25, 1854. Of special note is Kipling’s play on the word “charge” in the last line.

Kipling in his study at Naulaka USA 1895 (Wikipedia)

The Last of the Light Brigade

by Rudyard Kipling (April 28, 1890, St. James’ Gazette)

There were thirty million English who talked of England’s might,

There were twenty broken troopers who lacked a bed for the night.

They had neither food nor money, they had neither service nor trade;

They were only shiftless soldiers, the last of the Light Brigade.

They felt that life was fleeting; they knew not that art was long,

That though they were dying of famine, they lived in deathless song.

They asked for a little money to keep the wolf from the door;

And the thirty million English sent twenty pounds and four!

They laid their heads together that were scarred and lined and grey;

Keen were the Russian sabres, but want was keener than they;

And an old Troop-Sergeant muttered, “Let us go to the man who writes

The things on Balaclava the kiddies at school recites.”

They went without bands or colours, a regiment ten-file strong,

To look for the Master-singer who had crowned them all in his song;

And, waiting his servant’s order, by the garden gate they stayed,

A desolate little cluster, the last of the Light Brigade.

They strove to stand to attention, to straighten the toil-bowed back;

They drilled on an empty stomach, the loose-knit files fell slack;

With stooping of weary shoulders, in garments tattered and frayed,

They shambled into his presence, the last of the Light Brigade.

The old Troop-Sergeant was spokesman, and “Beggin’ your pardon,” he said,

“You wrote o’ the Light Brigade, sir. Here’s all that isn’t dead.

An’ it’s all come true what you wrote, sir, regardin’ the mouth of hell;

For we’re all of us nigh to the workhouse, an, we thought we’d call an’ tell.

“No, thank you, we don’t want food, sir; but couldn’t you take an’ write

A sort of ‘to be continued’ and ‘see next page’ o’ the fight?

We think that someone has blundered, an’ couldn’t you tell ’em how?

You wrote we were heroes once, sir. Please, write we are starving now.”

The poor little army departed, limping and lean and forlorn.

And the heart of the Master-singer grew hot with “the scorn of scorn.”

And he wrote for them wonderful verses that swept the land like flame,

Till the fatted souls of the English were scourged with the thing called Shame.

O thirty million English that babble of England’s might,

Behold there are twenty heroes who lack their food to-night;

Our children’s children are lisping to “honour the charge they made-”

And we leave to the streets and the workhouse the charge of the Light Brigade!

Acknowledgment: My thanks to Terry Brighton for his book Hell Riders: The Truth About the Charge of the Light Brigade. The personal stories of the men who rode down that “valley of Death” gives life to their famous charge during the Battle of Balaklava.