Like Osprey But Corsets and Khaki with a Whiff of Steampunk: Great War Fashion by Lucy Adlington

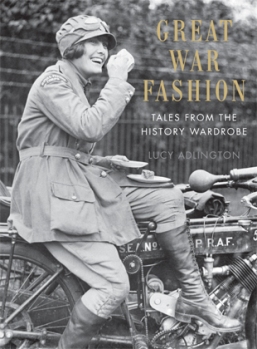

First, take a look at the young woman on the cover, “A despatch rider in the Women’s Royal Airforce enjoying a tea break while seated on her motorcycle, 1918.”

She’s most likely in a warzone. She’s probably not had a bath for a while. Might have lice. Any men in her life have a good chance of not making it to Christmas with all their body parts, or at all. She’s living under military discipline. And, as she rides around, she might herself get blown up or strafed.

And yet, she’s smiling.

You really have to read expert fashion historian Lucy Adlington’s Great War Fashion: Tales from the History Wardrobe to truly understand why she’s smiling.

And fashion in the book’s title is an understatement. This is more the kind of thing Osprey would publish — kit, context, consequences and case study. It’s certainly less about the minutiae of stitching and fabric, and more about the clothes women wore, why, how, and what the experience was.

As promised by the subtitle, “Tales from the History Wardrobe,” it’s packed with stories from women’s original letters, diaries and reminiscences, so it takes us beyond fashion and into the evolving role of women from about 1910 through to 1920.

The time span just touches Steampunk-able history, though people’s reactions to the swift evolution away from corsets and modesty also tell you a lot about the dog-end of Victorian values, casting light deeper into what was quite an unpleasant period in which to be a woman.

Now, that smile and why it’s there.

Yes, she could be posing for a publicity shot, but she, and women like her, really had some good reasons to smile…

First, she’s on a motorbike — actually, if you know female bikers you’ll know that that’s reason enough to smile — in a uniform performing a traditionally male role. People are taking her seriously. You’ll also note (horror!) the absence of any kind of chaperone or male protector, and the fact that she’s presumably riding around talking to Men of All Classes (shudder!). Her military unit will also be, if not entirely classless, much more egalitarian than she is used to and, if she is middle or upper class, free from the etiquette that once stifled her.

As she sips her tea, other British women in uniform are enjoying responsibility and respect in other spheres. Obviously, there are female spies and — as always — women crossdressing in order to be soldiers. However, there are female doctors running hospitals — not for the British, who would not allow it; our feminist heroes had to help out other nations — nurses drawn from all class, and, in the Serbian army one Sergeant Major Flora Sandes has tapped into the local “warrior maid” tradition and is winning medals leading her troops. Meanwhile, back home in Blighty, women are doing responsible jobs in factories, or serving as Land Girls, enjoying a similar egalitarian camaraderie, and discovering that men’s work is mostly just work.

When the war ends, there’ll be a tremendous effort to put the genie back in the bottle. Remember Major Flora Sandes? Here’s what she had to say:

I cannot attempt to describe what it now felt like, trying to get accustomed to a woman’s life and woman’s clothes again; and also to ordinary society having lived entirely with men for so many years. Turning from a woman to a private soldier was nothing compared with turning back from soldier to ordinary woman.

Now, since the Major mentioned it, let’s talk about the young woman’s clothes. Top to bottom:

Hair. OMG! What happened to her lovely long Edwardian-style hair? It’s… gone. That’s practically a flapper haircut, but half a decade too early, and practical is the point; long hair can be fun if you want to grow it, but mandatory long hair can be oppressive; like having a needy wombat in residence on your head. This young lady shed her hair when she took up her responsibilities and is probably happier for it — well look at that smile.

Corset (probably not present, or nominal only). You can’t tell, but if she is wearing a corset, it will be a practical one and not the tight-laced torture devices she will have encountered when she went through puberty.

Reading this book, you quickly realise that though some modern people love their corsets, most historical women loathed them. If anything, the Edwardian look was worse than the stuffier Victorian one because it achieved its apparent lightness through Even Tighter Lacing.

There are heart-rending accounts of early teenage girls being presented with their first corset and trying to hide it or destroy it; this in an era of ferocious child discipline. Old time corsets were mostly bad for the health, awful for the posture, and hardly fostered physical freedom.

Trousers. Up until World War One, women weren’t supposed to wear trousers. Even during the war, villagers threw stones and Land Girls who had committed the indecency of not wearing skirts, and respectable women covered their eyes rather than see cross-dressed performers on stage.

Skirts and dresses were of course horribly impractical. They were of physically restricting; we flinch to see women doing sport in them and lady hikers appear to have taken second sets of clothing with them for that glorious moment when they were beyond civilisation. They were also socially restricting because of all the stupid rules surrounding them, which brings us to…

Boots (visible). If you were an Edwardian woman and you showed more than an inch or so of boots, people would insult you in the street (and probably throw mud). The culture wasn’t entirely uncivilized — if it was raining, you could hike up the hem a little, and there were special clips to let you do this without flaunting some leather-shod ankle.

So, our young biker woman is not smiling because she is a soldier in a war zone, but because she is a successful refugee from the Edwardian Period. Being in uniform, in danger, surrounded by rolling tragedy is actually better than corsets and skirts and a “woman’s proper place”.

As you’ll have gathered, Great War Fashion (US, UK) is an amazing read. It’s also a very useful resource for anybody wanting to understand women’s experience of this era well enough to write about it or recreate it. Lucy Adlington — video here — has a new book coming out called Stitches in Time which looks to give the same treatment to women’s fashion throughout British history. As a Historical Novelist, I certainly plan to read it…

M Harold Page (www.mharoldpage.com) has written more historical fiction than he expected, but is soon making up for it by launching an old-school Heroic Fantasy trilogy, Swords Versus Tanks which just happens to contain WWI style tanks. While you’re waiting for that, you can buy his action-packed Dark Age adventure, Shieldwall: Barbarians! (UK, Epub) and also learn how to plan and write your novels using Storyteller Tools (UK, Epub).

Harold, thanks for the heads up on this book. I’ve just requested a copy from my local library. Some of Lucy Addlington’s statements are not limited to the Edwardian age although the contrasts were sharper then. Even until the hippie movement in the mid-60’s, women wore tight girdles and garter belts, not the light slender ones seen today. Ours were heavy with thick straps and very rigid and uncomfortable. I still remember the sheer joy of free movement when I put on my first pair of pantie hose. No more tight and restrictive garters. Clothing restrictions also applied to pants. We weren’t allowed to wear them to work unless it was a pants suit (matching pants and jacket.) I also related to Major Sandes statement about the jolt of going back to *civilian* life. It wasn’t only female solders, it was the wives of soldiers. It was difficult adapting when my husband was drafted. I learned to take care of the car, house and finances and did it for two years. I made different decisions. In those days most young couples put re-tread tires on their cars and often had blowouts. Since my husband wasn’t there to change tires, I put on new ones. I also remember when he got home from serving in Viet Nam, we were on a short trip and the car developed a problem. We pulled into a gas station (in those days service station meant service) and I started to get out of the car when it stopped. He said. “No, you don’t need to get out. This will only take a minute.” At that moment I realized the *ownership* of the car transferred from me to him. I felt bereft. I had lost something important and I didn’t know what it was. I suspect that the traditional wife and husband roles are also blurred in today’s army personnel. It’s discombooberating (great word that I haven’t used in a long time) to both sides.

Thanks again. I’m looking forward to reading Addlington’s book.

A friend of mine said, “The past is a foreign country; mostly Iran.”

I’m very glad you found my review useful and enjoyed reading your comment.