Discovering Robert E. Howard: David Hardy on El Borak – The First and Last REH Hero

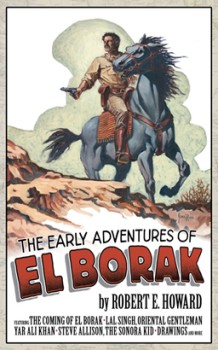

Today, our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series talks about my favorite REH stories: those featuring El Borak. David Hardy wrote the introduction to the Robert E. Howard Foundation’s The Early Adventures of El Borak and he also contributed what is essentially the afterward to Del Rey’s El Borak and Other Desert Adventures. There’s no one better suited to expound on Francis Xavier Gordon, so enough blathering from me. Let’s check out ‘The Swift.’

Today, our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series talks about my favorite REH stories: those featuring El Borak. David Hardy wrote the introduction to the Robert E. Howard Foundation’s The Early Adventures of El Borak and he also contributed what is essentially the afterward to Del Rey’s El Borak and Other Desert Adventures. There’s no one better suited to expound on Francis Xavier Gordon, so enough blathering from me. Let’s check out ‘The Swift.’

Francis Xavier Gordon, known from Stamboul to the China Sea as “El Borak”-the Swift-is perhaps the first of Robert E. Howard’s characters, and the last. El Borak is one of those distinctive characters that could only come from the fertile imagination of REH. He is a Texas gunslinger from El Paso, an adventurer, who has cast his lot in the deserts and mountains of Arabia and Afghanistan. There’s a little bit of John Wesley Hardin in his makeup, a bit of Lawrence of Arabia, and just a touch of Genghis Khan.

Howard described the origin of Gordon and other characters to Alvin Earl Perry: “The first character I ever created was Francis Xavier Gordon, El Borak, the hero of “The Daughter of Erlik Khan” (Top Notch), etc. I don’t remember his genesis. He came to life in my mind when I was about ten years old.”

That would put El Borak’s origins about 1915, the year Rafael Sabatini’s pirate novel The Sea Hawk appeared. The titular Sea Hawk is an Englishman who joins the corsairs of the Barbary Coast. There is also a supporting character named El Borak. Howard also noted that Bran Mak Morn, hero of “Worms of the Earth,” bore a resemblance to El Borak.

Howard made a number of abortive efforts at writing Gordon stories in the early 1920s. Howard was experimenting with Gordon, teaming him up with an early version of Steve Allison (the Sonora Kid) in stories that borrow motifs from H. Rider Haggard, Talbot Mundy, James Fenimore Cooper, Achmed Abdullah, and Howard’s love of exotic tribes and their weaponry.

One fragment tells of El Borak’s rescue of an Englishwoman from Pathan raiders, a classic theme of many Westerns (Last of the Mohicans, The Searchers) transposed to the Northwest Frontier of India. Perhaps the oddest of the lot is a science fiction tale where Gordon, in full Genghis Khan mode, bent on conquering a Middle Eastern kingdom, fights a battle-robot in hand-to-hand combat.

In the mid-1930s, Howard wrote several stories about a similar character, Kirby O’Donnell, which were swashbuckling, but O’Donnell lacks the bold decisiveness of El Borak. It didn’t help that O’Donnell appeared in a two-part story, and the two parts were sold to different magazines. A third O’Donnell story remained unsold and was re-written as a Conan tale by L. Sprague de Camp (“The Trail of the Bloodstained God”).

Howard also wrote “The Fire of Asshurbanipal,” which featured a Texan protagonist, Steve Clarney, and his Afghan comrade on a treasure hunt in Arabia. The story exists in two forms, one without any fantastic elements, and one with a Lovecraftian monster that was published in the December 1936 issue of Weird Tales.

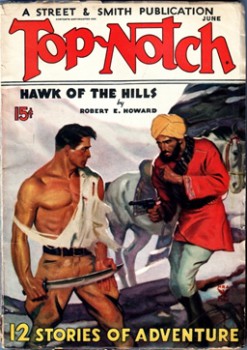

It was not until 1934 that El Borak returned. Howard had achieved no small success with Kull, Conan, Bran Mak Morn, Solomon Kane, Sailor Steve Costigan, and Breckinridge Elkins, making El Borak the last of his major characters to hit print. “The Daughter of Erlik Khan” appeared in the December 1934 issue of Top Notch. Howard had all the pieces on the board. Gordon is by turns a swaggering swordsman, and a man willing to risk his life to save a friend’s life, or avenge his death.

There are treacherous English adventurers (think Peachy Carnehan and Daniel Dravot gone rotten), a horde of Turkoman bandits, and a princess imprisoned in an ancient castle complete with an evil monk, hidden passages, and a vast treasure. Howard had his Western gunfighter in an Eastern adventure, with nods toward Haggard’s Lost Race stories, Kipling’s Empire tales, and the Gothic.

The core of it all is Gordon. He is a bit of chameleon, a man who puts on theatrical airs when it suits his purposes, who might appear to be an outlaw looking to loot the nearest treasure hoard, but is truly motivated by loyalty to friends. At the same time he is a hero from a Western.

The tales of the British Empire then in vogue tended to have similar settings, the Hindu Kush, the deserts of Arabia or Africa. But their heroes were often empire-builders, soldiers of the queen (e.g. the protagonists in Lives of a Bengal Lancer and Charge of the Light Brigade). By contrast El Borak serves no man. Like a drifting cowboy, he follows his own code and his own path.

“Hawk of the Hills” plays up Gordon’s independent streak. The story could be read as a range-war story transposed from cattle country to the Afghan hills. But in Central Asia, there is no sheriff and Gordon can indulge his Texan proclivity for feuding to the fullest. The part of the sophisticated “Easterner” seeking to put an end to the feud is taken by Willoughby, a British diplomat. Instead of a climactic quick-draw gunfight, there is a sword duel, with dramatic results.

The run of El Borak stories in Top Notch continued with “Blood of the Gods” in the July 1935 issue. Both “Hawk of the Hills” and “Blood of the Gods” were cover features, but the run ended there. The next El Borak story, “The Country of the Knife,” did not appear until August of 1936 in the pages of Complete Stories. The story puts El Borak into a city of outlaws hidden in a remote part of Afghanistan. Gordon is there partly to rescue a young man investigating a friend’s murder, and partly to stop a ruthless renegade’s plot to start a rebellion and sweep through India as a conqueror.

“Country of the Knife” brings Gordon back around to the theme of the self-willed adventurer who rises from nothing to become a warlord. Howard had toyed with the idea in the early Gordon stories. Of course both Conan and Kull are such men. But where Conan and Kull’s worlds are chaotic ones, in need of a strong hand to seize power and protect the weak, Gordon’s world is more or less stable. Instead of greed for power, El Borak risks his life to keep peace, or at least as much peace as a man like Gordon can stand.

“Country of the Knife” brings Gordon back around to the theme of the self-willed adventurer who rises from nothing to become a warlord. Howard had toyed with the idea in the early Gordon stories. Of course both Conan and Kull are such men. But where Conan and Kull’s worlds are chaotic ones, in need of a strong hand to seize power and protect the weak, Gordon’s world is more or less stable. Instead of greed for power, El Borak risks his life to keep peace, or at least as much peace as a man like Gordon can stand.

There were two other El Borak stories that were never published in Howard’s lifetime. “The Lost Valley of Iskander” is a genuine Lost Race story. While being pursued by villain intent on conquering India, El Borak stumbles into a city of Greeks dwelling in the mountains of Afghanistan.

They are descendents of Alexander the Great’s soldiers, living as the Ancient Greeks did. By tradition their leader is the strongest man in the city, setting up a wrestling match between El Borak and Ptolomy the Strong. It’s a mix of the Oriental adventure and a boxing story, a nice example of the way Howard blended genres to suit his interests.

The other El Borak story that went unsold was the novella “Three-Bladed Doom,” which exists in a long and short version. The long version was re-written as a Conan story under the title “The Flame Knife” by L. Sprague de Camp. Like “Country of the Knife,” “Three-Bladed Doom” relies on the “hidden city” motif and the theme of a conspiracy to conquer India.

This time the angle is a revival of the Hashashin, better known as the Assassins, the Medieval Islamic sect known for carrying out spectacular public assassinations of their enemies with killers trained to believe that they had seen paradise, and were headed there directly. In Howard’s hands the modern Hashashin are a confederacy of every devil-worshiper and outlaw sect in Asia, armed with everything from swords to bolt-action rifles, and funded by oil money. The castle is suitably Gothic, with legends of the Khan of Kwarazem, secret passages, and a monster dwelling in a maze. In classic Howard style, El Borak arrives and mayhem ensues.

The last El Borak story, at least the last one Howard composed, was “Son of the White Wolf.” It was published in the December 1936 issue of Thrilling. The story is the only one that connects Gordon with Lawrence of Arabia, the English military adviser to the Arab rebels in World War I. The story begins with the villain, one of the most memorable of Howard’s renegade conquerors, Lieutenant Osman of the Turkish Army. As the Turkish Empire crumbles, Osman leads his men in a mutiny, proclaiming adherence to the White Wolf, the totem of the pagan Turks.

Osman’s goal is not a new political party, but a new race. He begins by slaughtering the nearest Arab village and seizing their women, including a German spy, to provide “wives” for his mutinous troopers. El Borak reacts to avenge the death of his friends, and, like a Fenimore Cooper hero, to rescue the captive German woman.

“Son of the White Wolf” is a grim and bloody tale, not too distant in tone from Red Nails the last Conan story. Osman is a long way from the villains of “Country of the Knife” or “The Lost Valley of Iskander” with their somewhat quaint schemes of conquest. Osman is a racialist totalitarian, of the type that created Auschwitz and the gulag. But for all the dark implications, El Borak wins, and Osman’s schemes are stopped in a classic Howardian bloodbath.

In a sense it is the final maturation for Gordon. The character that began in a ten year-old’s imagination of Cowboys and Indians, played by a script from the Arabian Nights, that passed through half-told tales of treasure hunts and power-seeking, became a hero that fights on behalf of those who need a defender.

Of course El Borak is fictional, one might speak of Robert E. Howard’s maturation as a writer. Equally, one may question the need for maturity in a writer. Readers want stories that keep their interest, that in itself is sufficient. Maturity, social themes, a correct attitude may or may not be what a reader desires, and no reader requires justification for reading what they desire.

Every critic speaks for himself. I’ll say that since the day I brought home the battered copy of “Lost Valley of Iskander” that sits by my computer, I’ve never had cause to find Robert E. Howard’s tales of Francis X. Gordon, El Borak, known from Stamboul to the China Sea, to be anything less than enthralling.

Prior posts in our ‘Discovering Robert E. Howard’ series:

REH Goes Hard Boiled by Bob Byrne

The Fists of Robert E. Howard by Paul Bishop

2015 Howard Days by Damon Sasser

Solomon Kane by Frank Schindiler

REH in the Comics – Beyond Barbarians by Bobby Derie

Rogues in the House by Wally Conger

By Crom – Are Conan Pastiches Official? by Bob Byrne

The Worldbuilding of REH by Jeffrey Shanks

Re-reading ‘The Phoenix on the Sword” by Howard Andrew Jones & Bill Ward

Ramblings on REH by Bob Byrne

Pigeons From Hell by Don Herron

And we’re only about half way through the series: Stay tuned!

Dave Hardy is a former member of the Robert E. Howard Press Association and has written for REH: Two-gun Raconteur and The Cimmerian. His novels Crazy Greta and Palmetto Empire are available from Rough Edges Press. He lives in Austin with his wife and daughter.

You can read Bob Byrne’s ‘The Public Life of Sherlock Holmes’ column here at Black Gate every Monday morning.

He founded www.SolarPons.com, the only website dedicated to the ‘Sherlock Holmes of Praed Street’ and blogs about Holmes and other mystery matters at Almost Holmes.

His “The Adventure of the Parson’s Son” is included in the largest collection of new Sherlock Holmes stories ever published.

I think the El Borak stories (at least, most of the ones in the Del Rey volume), contain some of REH’s best writing.

agreed

I have been a Howard reader for over 40 years and enjoy his style and story prose much, El Borak being a favorite character of mine. Being a Texan as well I am happy that a fellow Texan created such good characters and stories that have lasted for this long, too bad he did not live longer to enjoy success.

[…] E. Howard (Essential Malady): El Borak has the distinction of being the first character created by Robert E. Howard though the stories he appeared in had a long gestation and weren’t […]