If You Think Kidney Stones are Painful, Try Passing a Blarney Stone: The Crock of Gold

Have you ever owned a book for many years, a book that you have always intended to read when just the right moment came around, a book that you looked forward to, anticipating the great pleasure that you would experience once the time finally came to dig into it? Yes? Then you know how dangerous such prolonged anticipation can be.

Have you ever owned a book for many years, a book that you have always intended to read when just the right moment came around, a book that you looked forward to, anticipating the great pleasure that you would experience once the time finally came to dig into it? Yes? Then you know how dangerous such prolonged anticipation can be.

I bought my oversized Collier paperback of James Stephens’ 1912 fantasy The Crock of Gold sometime in the mid-seventies (probably at the wonderful Change of Hobbit bookstore in Los Angeles) and it has been resting quietly on my shelf for most of my life, now and then whispering to me as I passed by, busy on long-forgotten errands, but I always put it off, promising that I would return when I was thoroughly ready to bestow my full attention on “a wise and beautiful fairy tale for grownups.” (Ah, the arcane art of blurb writing! Hmmm… sounds like a good Black Gate article. Let me finish this one first…)

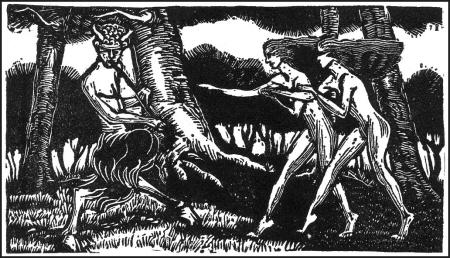

Last week, I took the book down, flipped through it, looked at the striking woodcut illustrations by Thomas Mackenzie, and decided that the long-deferred day had at last arrived… alas.

James Stephens, who was born in 1880 and died in 1950 was, according to the back cover of my paperback, “one of the best-loved of modern Irish writers.” I don’t know about that, but James Joyce had a high enough regard for Stephens’ talents as a poet and novelist to ask for his assistance in finishing Finnegan’s Wake, a scheme that never came to anything, probably to the relief of both men.

The Crock of Gold is one of the few of Stephens’ many books that is still in print, a sad fate for a national institution. The novel tells of a farmer, Meehawl MacMurrachu, who steals the hidden gold of the Leprecauns of Gort na Cloca Mora, setting off a wild chain of events that eventually involves almost everyone on the Emerald Isle, from the ancient gods of Eire to the befuddled local police.

MacMurrachu does not take the gold out of any desire for wealth — he is just retaliating because the Leprecauns have stolen his wife’s washboard, which they have done because the farmer’s cat killed a bird the day before. It’s that kind of book.

That is all the summary that I will attempt because the plot is so muddled and aimless and contradictory that it is usually impossible to tell what any character is doing or intends to do and equally impossible to grasp what is actually happening or why. When the book ended I didn’t know where I was any better than I did when it began, largely because of a host of stop-dead passages like this:

Angus had told her that beyond this there lay the great ecstasy which is Love and God and the beginning and the end of all things; for everything must come from the Liberty into the Bondage, that it may return again to the Liberty comprehending all things and fitted for that fiery enjoyment. This cannot be until there are no more fools living, for until the last fool has grown wise wisdom will totter and freedom will still be invisible. Growth is not by years but by multitudes, and until there is a common eye, no one person can see God, for the eye of all nature will scarcely be great enough to look upon all the majesty. We shall greet Happiness by multitudes, but we can only greet Him by starry systems and a universal love.

We Irish have a name for this kind of well-oiled, windy bullshit — we call it blarney.

While a small dose of it can occasionally be pleasing in its fortune-cookie way, it literally takes up about half of The Crock of Gold‘s 228 pages, which is way too much. (One of the main characters is simply named The Philosopher, which should have been warning enough if I had been paying attention. It could have been worse — there are two Philosophers when the story starts, but mercifully, one of them dies almost immediately.)

It gets especially thick when Stephens starts to hold forth about the sexes, to wit:

It gets especially thick when Stephens starts to hold forth about the sexes, to wit:

She said to Seumas that his fatal day would dawn when he loved a woman, because he would sacrifice his destiny to her caprice, and she begged him for love of her to beware all that twisty sex. To Brigid she revealed that a woman’s terrible day is upon her when she knows that a man loves her, for a man in love submits only to a woman, a partial, individual and temporary submission, but a woman who is loved surrenders more fully to the very god of love himself, and so she becomes a slave, and is not alone deprived of her personal liberty, but is even infected in her mental processes by this crafty obsession. The fates work for man, and therefore, she averred, woman must be victorious, for those who dare to war against the gods are already assured of victory: this being the law of life, that only the weak shall conquer.

I pause here to remind my readers of both sexes that I didn’t write this stuff — I’m just reporting on it.

There are pleasures in the book — Stephens’ descriptions of nature have a genuine quiet poetry about them (there are a couple of amusing scenes where animals talk to each other and make ironic and understated observations about their lives), and the dialogue is occasionally witty and sly, especially when it involves the cops, a species of humanity that seems to bring out the best in many writers.

Even the clotted chunks of philosophizing now and then yield a genuinely wise or memorable observation or aphorism. (These are easy to miss, though, because when they do turn up, the reader has already been beaten bloody by pages and pages of the kind of thing I quoted earlier.)

There are also two short passages concerning the poor and downtrodden of Ireland that are quite moving; Stephens’ depth of feeling comes through in these scenes largely because they are so simply told. If only for a moment, he abandons the elaborate abstractions and anchors these heartbreaking passages with small, everyday details. You would think that would have told him something.

There are also two short passages concerning the poor and downtrodden of Ireland that are quite moving; Stephens’ depth of feeling comes through in these scenes largely because they are so simply told. If only for a moment, he abandons the elaborate abstractions and anchors these heartbreaking passages with small, everyday details. You would think that would have told him something.

But by the end of the book, the only pleasure comes from the poetic and outlandish names, many of them gods and legendary heroes: the Thin Woman of Innis Magrath, Angus Og, Bove Derg the Firey, Glomhar O’Glomrach, Lugh of the Long-Hand, Mananaan Mac Lir, Credh Mac Aedh of Raghery, Dagda Mor, The Father of Stars.

At one point even Pan shows up. Just what the hell he’s doing in Ireland I don’t know, and neither does he (a wrong turn at Albuquerque?); he needs at least two more names and twelve more consonants to be eligible to participate in this yarn. He hangs around for one chapter and then seems only too glad to beat a hasty retreat out of the story, certifying him as the Wisest of the Wise.

The mythical figures all gather for the story’s climax — which never really happens. The immortals congregate, and then the book just peters out, in a rush of vague philosophic-spiritual verbiage. It doesn’t matter much; by that point I was ready to toss the book out of a window, but I couldn’t. I was on an airplane.

The mythical figures all gather for the story’s climax — which never really happens. The immortals congregate, and then the book just peters out, in a rush of vague philosophic-spiritual verbiage. It doesn’t matter much; by that point I was ready to toss the book out of a window, but I couldn’t. I was on an airplane.

Even after trudging through this very flawed story (the hopes of forty years dashed!), I can’t find it in myself to be angry at James Stephens. (He wouldn’t care, anyway, being dead.) The Crock of Gold isn’t hack work — it is clearly a seriously intentioned book overflowing with ideas and energy.

Ideas and energy are, however, things that only get in the way when they are as unfocused and undisciplined as they are in this wooly tale. I can’t avoid giving Stephens credit for good intentions, and I respect his novel — I only wish I had liked it. The good things in the book are genuinely good; there simply aren’t enough of them.

I’m sorry to say that on the whole, The Crock of Gold is mostly just a crock.

Thomas Parker’s most recent article for us was “The Woman Who Was a Man Who Was a Woman: Alice Sheldon and James Tiptree Jr..”

I read the book many years ago and enjoyed it, but I’m afraid you may have a point when you say the book is verbose. This is pretty representative of Stephens’ work as a whole. He’s known for one other book – ‘The Charwoman’s Daughter’, a very slight, if pleasant, work, and a handful of short stories, one of which, ‘Etched in moonlight’ is worth checking out.

The introduction of Pan (doesn’t the whole classical pantheon turn up at the end of the book?) seems to have been a feature of the time, when most people had read the classics and tried to incorporate them into their own indigenous mythology, but whereas Mr Tumnus works fine in the LWW, in this case the classical element seems actively incongruous.

Stephens also wrote “The Demi-Gods” which is about a group of tinkers – there’s a loaded word – travelling the length and breadth of Ireland accompanied by three angels. I read the book some years ago and came away as confused as you seem to be with “The Crock of Gold”. The introduction to my copy states that it is a funnier and more profound work than Crock. I wonder if Flann O’Brien’s “Third Policeman” is a parody of Stephens’ meanderings. It contains policemen, it wanders back and forth in a Groundhog like manner and then it has a rather sinister ending. Certainly, when I read that work, I did not feel that I was wandering around to no purpose. Neil