The Three Phases of Marvel’s Adam Warlock, Part Two: The Magus Saga

Read The Three Phases of Marvel’s Adam Warlock, Part One here.

Read The Three Phases of Marvel’s Adam Warlock, Part One here.

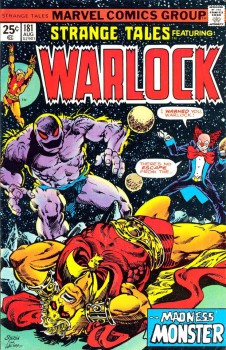

My 10-year old son saw my Warlock comics (the ones showing the clowns and the Madness Monster I’ll discuss in this post) this morning and asked who Warlock was and why his villains were so weird. Then, of course, being ten, he asked if I could get him some Warlock comics. And I explained to him that he might not like them.

Warlock is a very sad hero, I explained. He tries to be good, and tries to make good choices, but all that ever happens is that people around him get hurt or he fails. I think that’s a good way to start this post.

I should also note that this post is constructed entirely of spoilers. 100%, wall-to-wall spoilers of a thirty-year old story. Embrace the spoilers.

In my last segment, I looked at the hero Adam Warlock, from his synthetic birth as “Him” in the 1960s to his rechristening as a messiah figure in 1972 and 1973 and eventual cancellation. This first period was an important start to what I said to my son. Adam Warlock tried to save Counter-Earth and ultimately, he could not expunge the evil in men and he left for the stars.

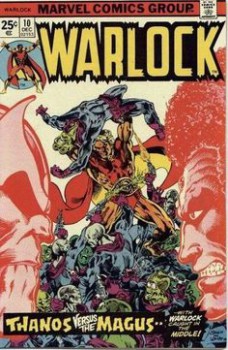

The second phase of the saga is the Jim Starlin as writer/artist era, which I measure from 1975 until the hero’s death in 1977. Jim Starlin produced two classic stories in this phase, the Magus arc and the Thanos arc. These are big and original for the comics of the time, so I’m going to cover the Starlin period in two posts. Today is the Magus saga.

Starlin’s shockingly detailed art and mature, artist-driven writing (presaging Miller, to some extent) was a big surprise in Strange Tales #178.

Starlin’s shockingly detailed art and mature, artist-driven writing (presaging Miller, to some extent) was a big surprise in Strange Tales #178.

The story opens with a girl fleeing across a silent moonscape seeking Adam Warlock, but pursued by a religious execution team. Adam Warlock dismantles this black ops squad quickly, but not quickly enough to save the girl, and the execution squad teleports away, leaving no clues.

Here, Starlin adds the first of the powerful story threads that will make Adam Warlock so much more of a great and tragic hero. To find out who the girl’s murderers were, Adam takes the dying girl’s soul with the soul gem on his forehead.

This foreshadows the conflict between Adam and the vampiric gem on his forehead that will run from this moment to his death two years later. The girl’s soul tells him that she is a religious refugee, fleeing a star-spanning, persecuting theocracy led by the god called the Magus.

Offended by the idea of an unjust, immoral Church of Universal Truth, Adam decides he’s going to stop it.

But, in a deepening twist, the Magus, the god of this church manifests in a vision before him and reveals that he and Adam Warlock are one and the same being, and so Adam cannot fight him. Yeah. Whoa.

Thematically, the concerns of this hero and his story are like nothing seen previously in comics, except maybe for the Denny O’Neill/Neil Adams Green Lantern run or the Jack Miller/Neal Adams Deadman run, both of which were highwater marks for comics, but had decidedly more gritty, personal, and episodic concerns.

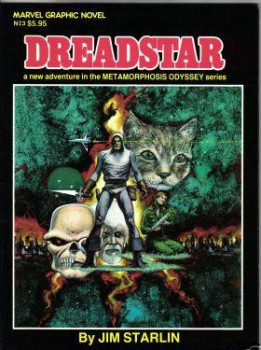

The vast physical and moral scope of a star-spanning religious empire is a motif that Starlin would return to in Dreadstar, his 1980s creator-owned work that appeared in Epic and later under the First Comics brand (covered in a detailed review right here at Black Gate by Matthew David Surridge just last month).

The vast physical and moral scope of a star-spanning religious empire is a motif that Starlin would return to in Dreadstar, his 1980s creator-owned work that appeared in Epic and later under the First Comics brand (covered in a detailed review right here at Black Gate by Matthew David Surridge just last month).

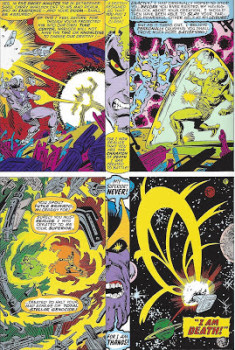

Artistically, Starlin’s Warlock is visually realistic and deeply textured. No one draws Adam Warlock’s brooding, loner intensity better than Starlin.

Warlock pursues the execution squad back to a church warship and is captured. This is the first clear view that Adam Warlock is travelling not only through a space voyage, but through a moral landscape of believers, non-believer, and the deformed who don’t fit into the Church’s theology.

It’s a powerful, sophisticated set of concerns for comics of the 1970s. Little do the religious fanatic warriors filling the ship know that they are in more trouble than Adam. He defeats them but, unexpectedly, when he faces the powerful captain of the fanatics, his soul gem takes over and consumes the captain’s soul.

This is another step down the path of tragedy for him, making of Warlock a hero much closer to Moorcock’s Elric than Spider-Man or the X-Men.

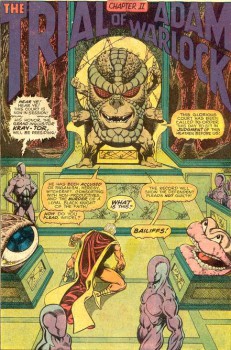

Adam continues his hunt for the Magus, to the homeworld of the Church of Universal Truth. The Matriarch of Church of Universal Truth traps him in a weird, surreal court setting where he is put on trial.

The obviousness of the moral landscape couldn’t be clearer, making this something in the same genre as Dante’s Inferno. The prosecutor is a mouth, the defender is an eye, the jury are mannequins, the bailiffs are murderous and all the witnesses invent crimes Adam has committed.

Warlock is sentenced to death and defends himself by (for the first time willingly) stealing a soul, this time the essence of the horrific judge. Becoming a murderer is too much for the former Christ-figure of Counter-Earth to absorb all at once, and he has a great line: “In his mind, I was a villain, and by stealing his soul, I proved him right.” Incapacitated, Adam Warlock is thrown into religious reindoctrination.

Warlock is sentenced to death and defends himself by (for the first time willingly) stealing a soul, this time the essence of the horrific judge. Becoming a murderer is too much for the former Christ-figure of Counter-Earth to absorb all at once, and he has a great line: “In his mind, I was a villain, and by stealing his soul, I proved him right.” Incapacitated, Adam Warlock is thrown into religious reindoctrination.

Adam wakes in a more powerfully morally surreal world of clowns. The chief clown explains that Adam has been sick, but can now see things as they truly are. This, of course is a VR experience produced by church indoctrinators, but they realize right away that Adam is distorting everything they are feeding him and that he’s perceiving the best of the church as clowns.

In Adam’s hallucination, they offer to give him clown paint, so that he can look like everyone else. He tries it and rejects it. He sees clowns punishing each other and the insanity of clowns building heaps of garbage that collapse each day, killing clowns each time. Adam feels like he’s going crazy, and demands to escape the surreal world and is told that the only way out is the Madness Monster.

Adam faces the Madness Monster, which turns out to be the dark side of himself he’s feared and kept hidden, the part which will birth the Magus. The only way to defeat it is to come to terms with it, ripping aside the veil of false morality, making of the moral landscape not good and evil, just different viewpoints. Warlock does come to terms with it, in effect, becoming insane.

Thus freed, and armed with a new, subtly warped view of reality, Adam finds the Magus, who, far from being an independent looney-toon, is actually a Champion of Life in the largest conflict in reality. The Magus has been made into a god of life by the powers of the universe because such a god is necessary to reality. The madness Adam has just internalized is a stepping stone to the worldview he will need, because it is now revealed that the Magus is nothing less than the future version Adam Warlock. Talk about cosmic peril.

The Magus bathes Warlock in a radiation that will attract the In-Betweener, a cosmic entity that will bring Warlock to his insane dimension where dark secrets will be whispered to him for centuries, transforming him into the Magus, after which Adam will emerge as the Magus 5,000 years in the past to found the Universal Church of Truth and take over the cosmos.

But Thanos, the mad Titan and worshipper of Death arrives, and spirits Warlock away. The Magus will one day become an impediment to Thanos’ plans so he is willing to help Adam commit suicide; not just his body, but suicide of the soul that will become the Magus.

But Thanos, the mad Titan and worshipper of Death arrives, and spirits Warlock away. The Magus will one day become an impediment to Thanos’ plans so he is willing to help Adam commit suicide; not just his body, but suicide of the soul that will become the Magus.

Magus follows with thousands of holy knights. Thanos cannot stop them and he tells Warlock to take their souls. Warlock refuses to commit mass murder and Thanos the villain scores one of the most powerful questions in the saga: “Who exactly will pay for your lofty morals now? The billions who will fall under the foot of your future self.”

So Adam murders a room full of knights to avert a greater evil, and goes through one of Thanos’ devices to a place where he can destroy the part of his soul that in the future will become the Magus. Left behind, Thanos and the Magus battle, with the Magus realizing that Thanos is the Champion of Death that he himself has been created to fight.

In a strange psychic world, where the different branching of his soul are laid out, Adam Warlock uses him soul gem on the one that leads to the Magus, thereby destroying the god. He’s won.

But in a powerfully poignant denouement, to avoid any other part of him becoming the Magus, Adam follows his new life’s pathway two years into the future to kill his future self.

There, he finds a tragic, failed self who has lost at everything and everyone. The Adam Warlock of two years in the future bitterly welcomes the death that the Adam Warlock of the present brings with his soul gem. Adam kills his self of two years in the future.

This is such a powerful storyline, so richly built with cosmic concepts that hint at the influences of Moorcock and Lovecraft, that I go back to this series every few years.

I am always floored by the power and creativity of the narrative and the daring of this writer-artist. In 1975 and 1976, Starlin took a failed messiah and gave him a fate awesome enough that the large conflict of reality was directly involved in it. Not only that, but Starlin made a tragically moral hero who was forced into one imperfect choice after another, and his true heroism is rejecting the war that he was being groomed to lead.

I’ll cover the next part of the 1975-1977 Jim Starlin era Warlock in a future post. In the meantime, if you want to check out any of this brilliant series yourself, I just checked and Comixology.com has it all.

Derek Künsken writes science fiction, fantasy and horror in Ottawa, Canada. He tweets from @derekkunsken and his website is www.derekkunsken.com. He’s got stories upcoming in The Year’s Best Science Fiction and Fantasy and The Year’s Best Military SF and Space Opera.

Jim Starlin used moral dilemma a lot and I didn’t understand that as a kid. Surreal writing is hard to follow even though the medium of a comic does it best. I didn’t appreciate him until his Dreadstar days and then I was long past Warlock. Thanks for the plug on Comixology. Those issues can be attained at a low low price. They definitely deserve a read.

I did not know that he had a Moorcock and Lovecraft influence. I know that the characters influence by an Elric type persona are easy to spot. I think I would have to agree with you. I wonder if Dan Abnett’s Maelus Darkblade character was influenced by Elric as well.

Thanos is one of the best villians made. I don’t know much about his earlier stories but did Starlin come up with him? Thanos is one of my favorites. They are hard to follow because they end up in a lot of different series. I just know that if he shows up the hero is in for a tough fight.

Great work sir!

Interesting! I remember the original series being in black-and-white (indeed, I don’t remember many comics being in colour around then), also that the Magus’s principal distinguishing features – ie, what differentiated him from his younger self – was his afro and a black star around one eye. A quick google reveals I got the first part right, but no black star. Such are the tricks that memory plays on you…..

Back in the early ’80s when I was a kid haunting the comic-book racks, anything drawn by Starlin (it would’ve been the Dreadstar stuff by then) jumped out at me. His artwork was really on another level from most of the comic art at the time.

Man, that full-page spread of The Trial posted above would’ve sold me on a comic right there — so beautifully laid-out and rendered, and trippy as hell: like a well-drawn LSD-inspired underground comic meets the Marvel Universe! Weird lip creature; weird eye creature; weird reptilian head creature: well, yeah, that’s worth 35 cents.

Hearing the complexities and moral resonance of the plot line summarized here makes me want to read these comics now.

[…] Adam Warlock was one of those brooding, tragic, lonely heroes I gravitated to as a thirteen-year old, along with Dr. Strange and Son-of-Satan and the oddball Defenders. I’ve broken up Warlock’s chronology into the three phases. I covered the first, the pre-Jim Starlin era, in my first post. I covered the first half of Jim Starlin’s 1975-1977 run, the Magus saga, in my second post. […]