Vintage Treasures: Sturgeon is Alive and Well… by Theodore Sturgeon

|

|

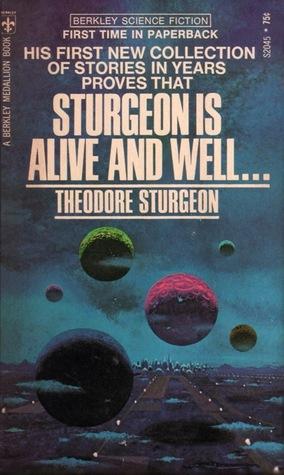

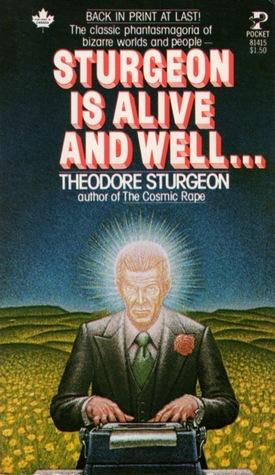

Sturgeon is Alive and Well… was Theodore Sturgeon’s fourteenth short story collection. It was first published in 1971, and came following a five-year gap after Starshine (1966). As I mentioned in my write-up on that book, Starshine went through nearly a dozen printings in as many years. But Sturgeon is Alive and Well… had only three: a hardcover in 1971, a paperback reprint the same year from Berkley Medallion (above left, cover by the great Paul Lehr), and a Pocket reprint in 1978 (above right, artist unknown.)

It’s now been out of print for 37 years, and there is no digital edition.

The title is… unusual. It probably made more sense in 1971, when Jacques Brel is Alive and Well and Living in Paris was an unexpected smash hit off-Broadway. Sturgeon touches on what a five-year gap between collections meant for a writer who made a living on short stories in his introduction.

Yes. I am alive and well.

Once to a perceptive friend I was bemoaning the fact that there was a gap in my bibliography from 1940 to 1946. (Actually some stories were published during that period, but only one had been written after 1940.) What wonders I might have produced had I not been clutched up, I wailed. And he said no, be of good cheer. He then turned on the whole body of my work a kind of searchlight I had not been able to use, and pointed out to me that the early stuff was all very well, but the stories were essentially entertainments; with few exceptions they lacked that Something to Say quality which marked the later output. In other words, the retreat, the period of silence, was in no way a cessation, a stopping. It was a silent working out of ideas, of conviction, of profound selection. The fact that the process went on unrecognized and beyond or beneath my control is quite beside the point. The work never stopped.

I’ve held hard to that revelation in recent years, and no longer go into transports of anguish when the typewriter stops. I do other things instead, in absolute confidence that when that silent subterranean work is done, it will surface. When it does so, it does with blinding speed — a short story, sometimes, in two hours. But to say I wrote it in two hours is to overlook that complex, steady, silent processing and reprocessing that has been going on for months and often years. Say then that I typed it in two hours. I do not know how long it took to write. I could only type it when it was finished.

There are 12 stories in Sturgeon is Alive and Well… With only one exception they were all written in the course of what Sturgeon calls “that astonishing summer.” He credits his fourth wife, the journalist Wina Golden — whom he began living with in 1969 — as his muse.

I was living at the bottom of a mountain in Neverneverland, far under a rock. Looking back on that time, I now know that I was unaware of just how far I had crawled and just how immobile my crouch. Suddenly one day there exploded a great mass of red hair attached to a laughing face with a beauty spot right in the center of her forehead and a totally electric personality. Her name was Wina and she was a journalist and a photographer and a dress designer and a dancer and she had traveled 6,500 miles with her cat (inside of whom she smuggled four kittens) to marry me. She crawled way in under that rock and hauled me out…

And suddenly I wrote. As I have said, I do not know how long it took me to write the stories, but I typed one a week for eleven consecutive weeks, and after a short hiatus, a twelfth — all while I was writing a novel.

Only one of the stories in Sturgeon is Alive and Well... was originally published in a science fiction magazine: the classic “Slow Sculpture,” which first appeaed in the February 1970 issue of Galaxy Magazine. It won both the Hugo and Nebula awards, and became one of his most anthologized stories.

Only one of the stories in Sturgeon is Alive and Well... was originally published in a science fiction magazine: the classic “Slow Sculpture,” which first appeaed in the February 1970 issue of Galaxy Magazine. It won both the Hugo and Nebula awards, and became one of his most anthologized stories.

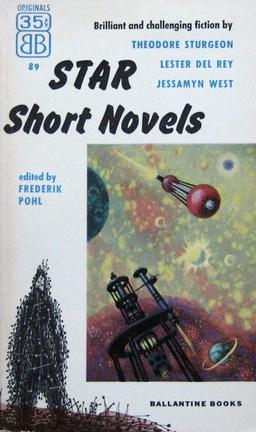

The 60-page novella “To Here and the Easel” was first published in Star Short Novels, the rest appeared in men’s magazines like Adam and Knight in the late sixties and early seventies.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Foreword by Theodore Sturgeon

“To Here and the Easel” (Star Short Novels, 1954)

“Slow Sculpture” (Galaxy Magazine, February 1970)

“It’s You!” (Adam, January 1970)

“Take Care of Joey” (Knight, January 1971)

“Crate” (Knight, October 1970)

“The Girl Who Knew What They Meant” (Knight, February 1971)

“Jorry’s Gap” (Adam, October 1968)

“It Was Nothing — Really!” (Knight, November 1969)

“Brownshoes” (Adam, May 1969)

“Uncle Fremmis” (Adam, 1970)

“The Patterns of Dorne” (Knight, May 1970)

“Suicide” (Adam, June 1970)

Sturgeon wrote only five novels, including More Than Human (1953), The Cosmic Rape (1958), and Godbody (1986). He is best known for his short fiction — and in fact, at the height of his popularity in the mid-50s, he was the most anthologized living author in the English language.

He is perhaps best known today for his screenplays, including two highly regarded Star Trek episodes: “Shore Leave” (1966) and “Amok Time” (1967). The latter is known for introducing pon farr, the Vulcan mating ritual, the first use of the phrase “Live long and prosper,” and the first use of the Vulcan hand sign.

Our most recent coverage of Theodore Sturgeon includes:

Not Without Sorcery (1961)

Sturgeon in Orbit (1964)

Starshine (1966)

Sturgeon is Alive and Well… (1971)

To Here and the Easel (1973)

The Stars Are the Styx (1979)

Sturgeon is Alive and Well… was originally published by Berkley Medallion in August 1971. It is 224 pages, priced at 75 cents. The cover is by Paul Lehr. It is currently out of print, and there is no digital edition.

See all of our recent Vintage Treasures here.

If Sturgeon truly is best known today for his screenplays for STAR TREK, good as they were, that’s pretty sad, because the amazing peaks of his short fiction output are what really matter.

Rich,

I’d love to hear evidence to the contrary. But I’ve covered six of his collections so far, and they’ve been out of print now (on average) about 35 years. No digital editions I can find, either.

There was the excellent The Complete Stories of Theodore Sturgeon (10 volumes?) from North Atlantic Books, and there ARE digital editions of those… but I have no idea if fans today are even aware of them.

I’m glad you quoted that first passage from his introduction, because I subscribe to that view whole-heartedly and have consoled myself with the same thought during periods of low output. And — like what he describes — when I do sit down again and write a story after a long hiatus, it often comes forth at white-hot speed, seemingly fully formed. “Say then that I typed it in two hours. I do not know how long it took to write. I could only type it when it was finished.” Yes.

I found it refreshing to discover that one of the most prolific and acclaimed short stories writers in the genre (or out of the genre, come to think of it) had a period of such low productivity for so long that he felt it necessary to tell readers he was still alive in the title of his fourteenth collection.

I for one am aware of the Complete Stories and have eleven volumes on the bookcase behind me as I type this. There were thirteen volumes. A quick check of Amazon shows they are still available in both hardcover and electronic format.