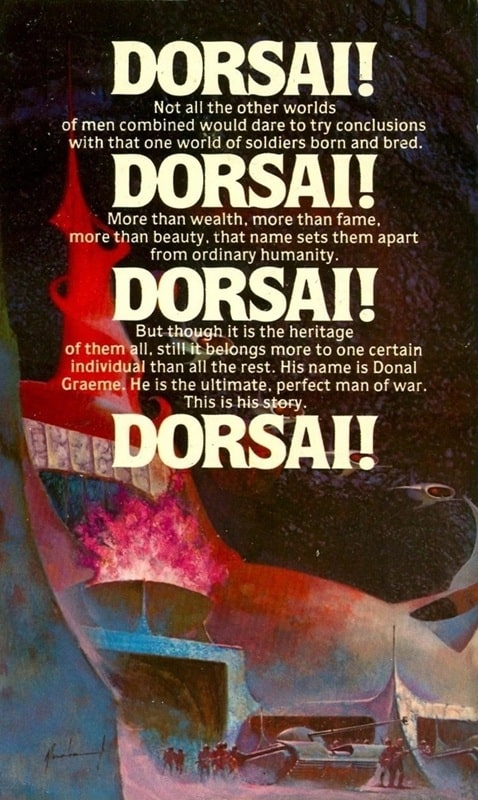

Shai Dorsai: Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson

|

|

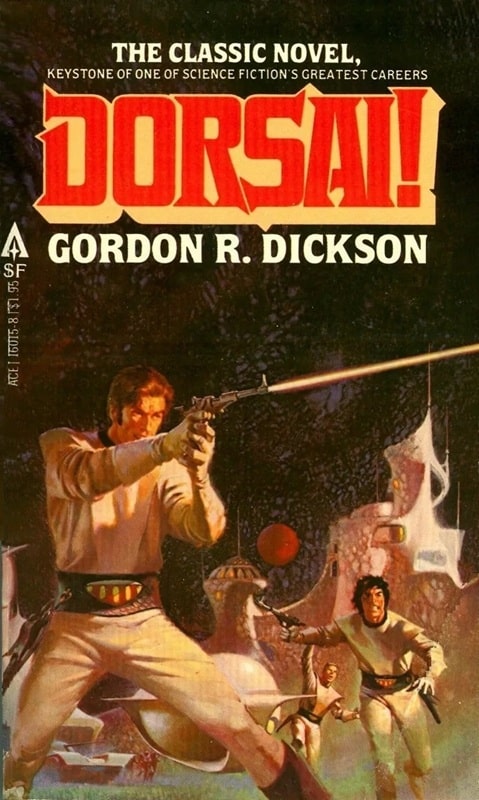

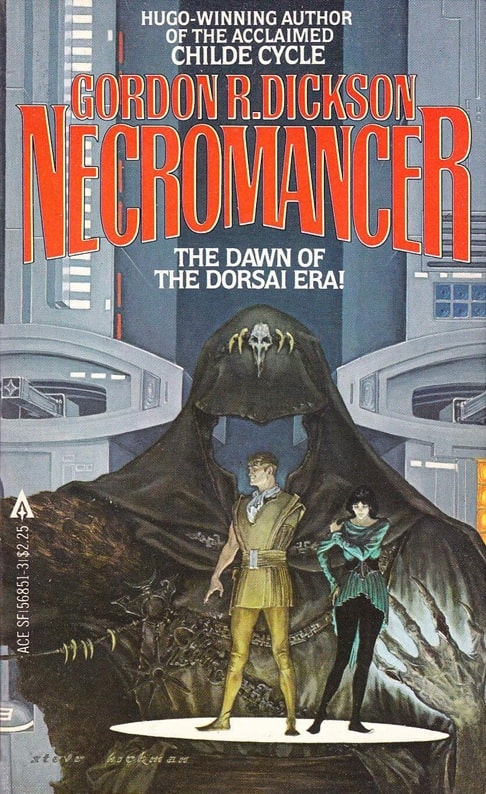

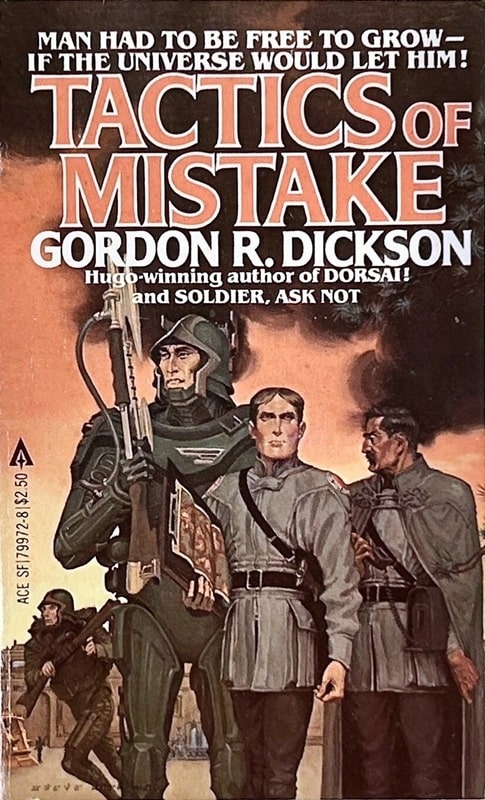

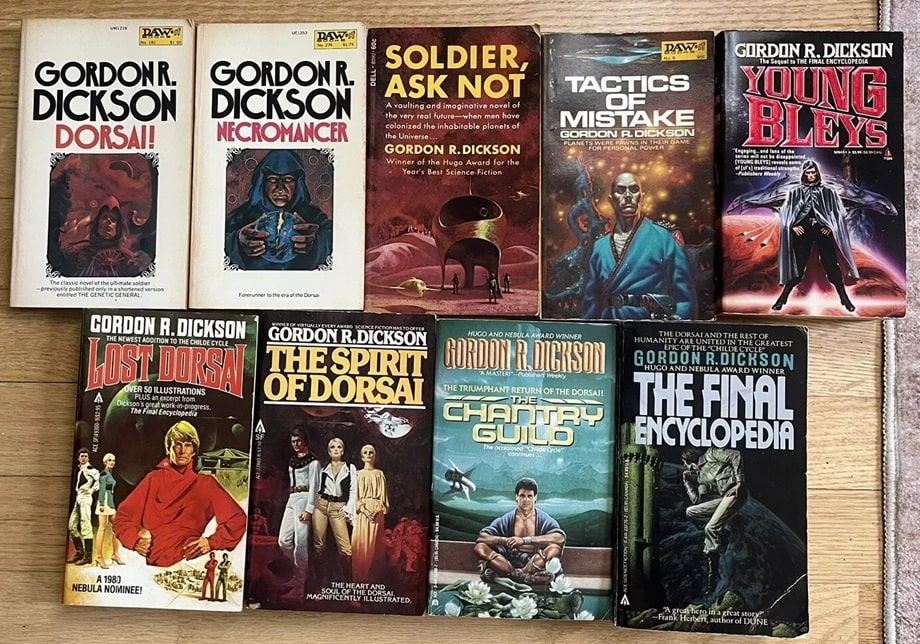

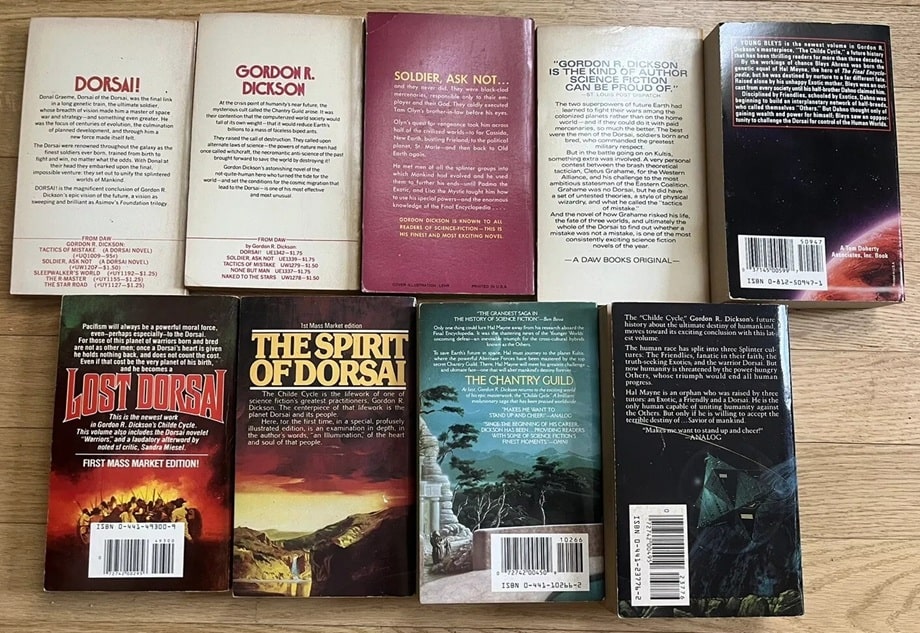

Dorsai! by Gordon R. Dickson (Ace Books, February 1980). Cover by Jordi Penalva

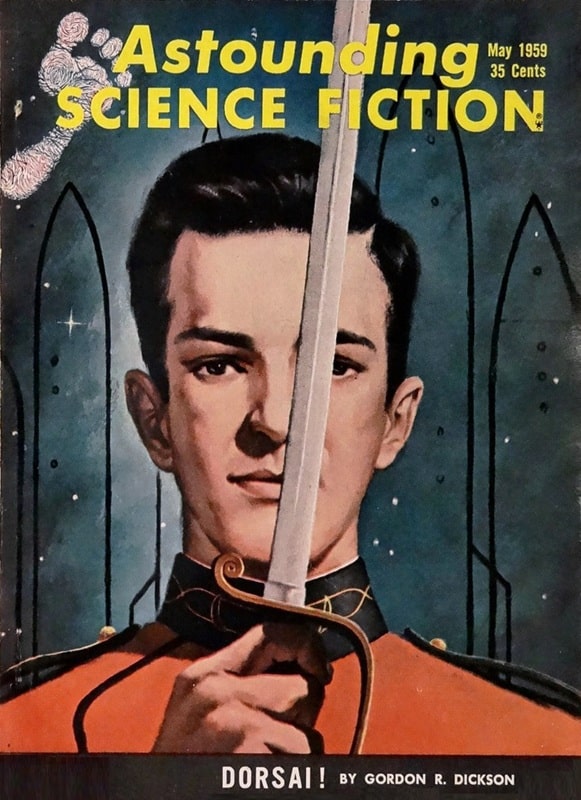

In 1959, Robert A. Heinlein published Starship Troopers, one of the founding works of military science fiction as a genre. But that same year saw the serialization of Gordon R. Dickson’s Dorsai! in Astounding Science Fiction, a work that may have been equally influential, though it seems now to be less remembered. In fact, both were nominated for the Hugo Award in 1960, though Starship Troopers won.

Dorsai! is set in an interstellar future, with some sixty billion human beings inhabiting 16 planets of eight solar systems. Several of the stars are named in the novel, and as was common at that time, many of them are astrophysically implausible candidates to have biospheres, being of spectral types with relatively short lifespans: Altair (type A7), Fomalhaut (type A4), and Sirius (type A0). Fomalhaut and Sirius are also multiple stars, which limits the possible planetary orbits around them. At least Ceta, orbiting Tau Ceti, is a plausible Earthlike planet! It’s also noteworthy that several of these solar systems have multiple habitable planets — though that’s also true of our own, where Dickson has Mars and Venus humanly colonized, a project that seemed far more daunting only a few years later!

But all this is somewhat beside the point, because unlike his lifelong friend Poul Anderson, Dickson isn’t writing about the physics of his planets, or the biology it enables. To a first approximation, his focus is sociology: the planets of his interstellar future have largely divided up into groups that emphasize different types of human activity, almost like the varnas [“castes”] of ancient India — and different ethical values along with them.

Thus, we have the “Venus group” (Venus itself, Newton, and Cassida), whose focus is on technology and the physical sciences; Ceta, a planet of commercial enterprises and investors; the “Friendlies,” Harmony and Association, two worlds of devout monotheists; the “Exotics,” Mara and Kultis, whose emphasis is partly philosophy (more in the Hindu or Buddhist style than in the Western) and partly a science of human potential, called ontogenetics, that apparently can be used for selective breeding for specific desired behavior.

|

|

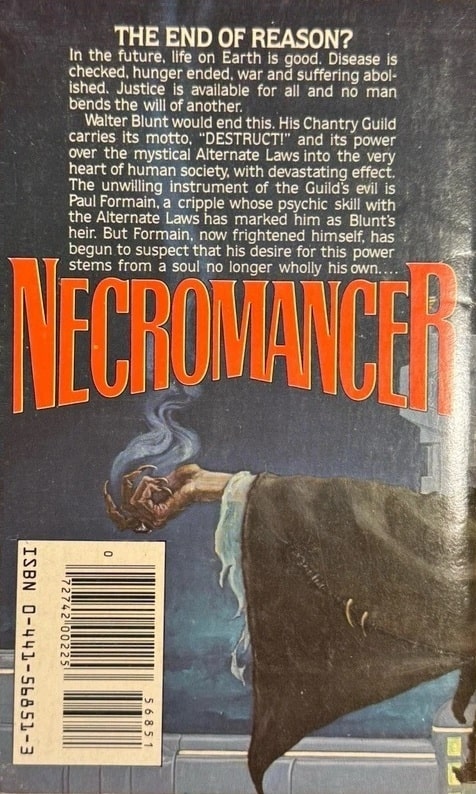

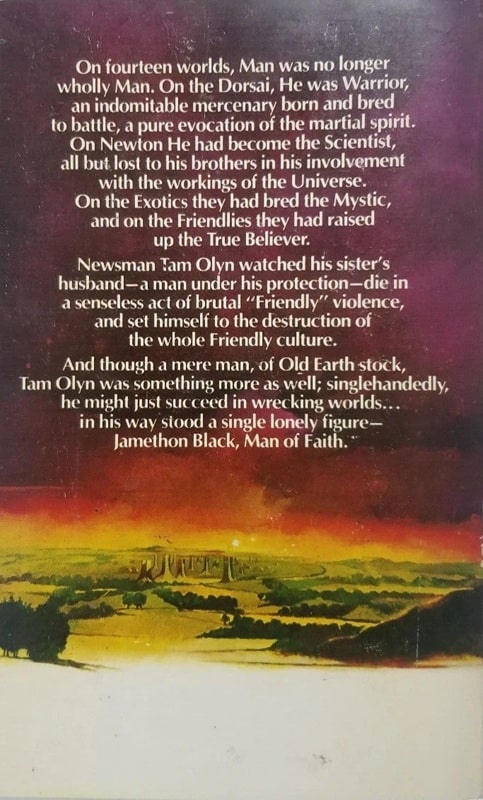

Book 2 in the Dorsai series: Necromancer (Ace, April 1981). Cover by Stephen Hickman

And then there’s the Dorsai, for whom the book (and several of its sequels) is named. It’s the name both of a planet and of the people who inhabit it. Compelled by a shortage of natural resources, their men hire out as mercenaries, known as the best soldiers in the humanly inhabited universe, both naturally talented at war and intensively trained. One of these is Dickson’s protagonist, Donal Graeme, the focus of the entire narrative.

This diversity of planetary societies sets up the novel’s conflict. In the first place, the planets are specialized, not merely in broad cultural patterns, but in economic detail. There are more specialized occupations than any one planet can afford to train for itself; the human race has a sixty-billion-person division of labor. This creates a need for specialists from each planet to travel to other planets where their services are needed, just as the Dorsai do.

|

|

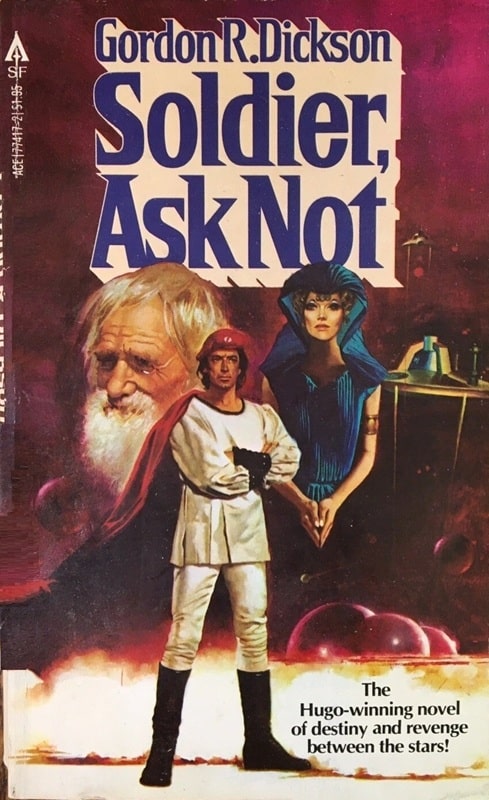

Dorsai, Book 3: Soldier, Ask Not (Ace, March 1980). Cover by Enric

But the terms on which they do so are set in different ways by different planets. At one extreme are the tight worlds: the technologically advanced Venus group, the religiously fanatical Friendlies, and Coby, a mining world controlled by a criminal cartel. At the other are Old Earth and Mars, described as “republican worlds”; the Exotics; and the Dorsai, which are counted as loose worlds.

In between are several miscellaneous worlds, including the commercial Ceta and two worlds with strong central governments, New Earth and Freiland. The tight worlds treat labor contracts virtually as indentures and are in a position to dominate the labor markets, putting them at odds with the loose worlds.

|

|

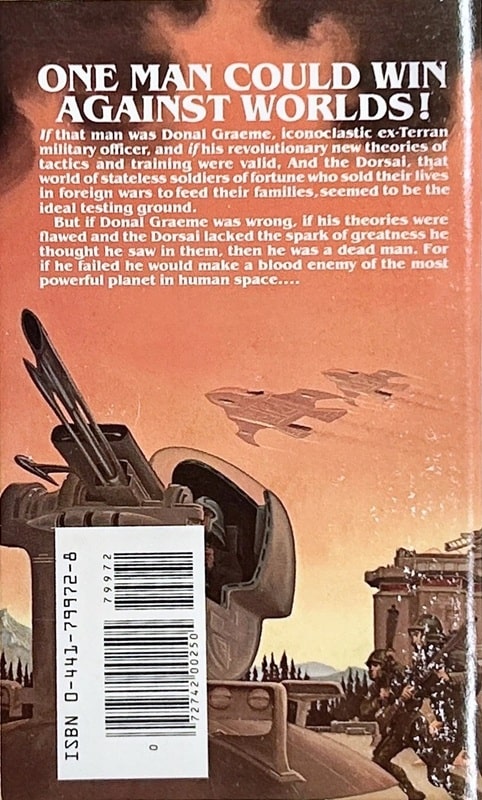

Dorsai, Book 4: Tactics of Mistake (Ace, May 1981). Cover by Stephen Hickman

It struck me on this reading that Dickson’s view of Harmony and Association seems to have changed as he wrote the series. Here they are harshly authoritarian societies with no evident redeeming features. In Soldier, Ask Not, published eight years later, they appear much more sympathetically, and it seems that Dickson’s unfinished final volume would have shown them as an essential element in the reunited human race — the element of faith, as the Dorsai are courage and the Exotics wisdom. (The other major tight faction, the Venus group, are seemingly left behind as having nothing essential to add to human destiny.)

Donal Graeme himself fits this theme of human reunification: both of his grandfathers were Dorsai, but both of his grandmothers Maran. (This hybrid ancestry made me think of another military genius in later science fiction, Lois McMaster Bujold’s part-Betan, part-Barrayaran Miles Vorkosigan.) This gives him a peculiar mix of abilities. He’s a brilliant warrior and commander, fitting a work of military fiction. But he also have some gifts that transcend normal humanity, as he’s told during his employment by the Exotics.

We get a foretaste of this when he finds himself able to walk on air, apparently simply by believing he can! But more profound than that is a peculiar kind of insight that deepens over the course of the novel, as a result of various stressful experiences. And that insight sets him up, almost from the outset, as an opponent of another major character: William of Ceta, a master entrepreneur whose aim is to take full advantage of the interstellar labor market.

Donal and William become both political and romantic rivals, but both rivals reflect Dickson’s underlying theme of human destiny and the question of who will shape it. In this theme, Dorsai! in a lot of ways transcends the category of military science fiction.

On one hand, this theme strikes me as more mythological than science fictional — which I’m not sure Dickson would even have disputed! On the other hand, it points the way toward the deeper emotional resonance of some of the later books, especially Soldier, Ask Not.

Dorsai! also sets a pattern Dickson will follow in later novels in the series, of presenting conflict ultimately not as a clash of institutions (despite his comments about loose and tight worlds) but as a collision of two larger than life figures on opposing sides: not so much realistic fiction as epic. This volume is a somewhat simple first presentation of the theme, but at the same time one of the clearest in the series.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels. His last article for us was a review of Singularity Sky by Charles Stross.