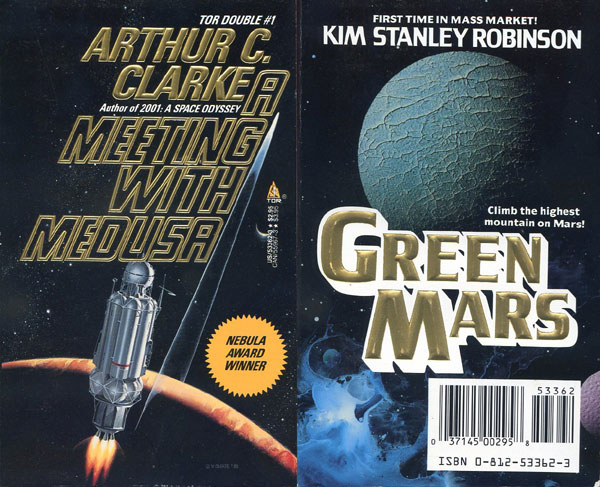

Tor Doubles #1: Arthur C. Clarke’s Meeting with Medusa and Kim Stanley Robinson’s Green Mars

Green Mars cover by Vincent di Fate

Tor Double #1 was originally published in October 1988. This volume marked the beginning of the official Tor Double series. The two stories included, Arthur C. Clarke’s Meeting with Medusa and Kim Stanley Robinson’s novella Green Mars complement each other, although by doing so, Green Mars also points out a weakness of Meeting with Medusa. The volume was published as a tête-bêche, with both covers were painted by Vincent di Fate.

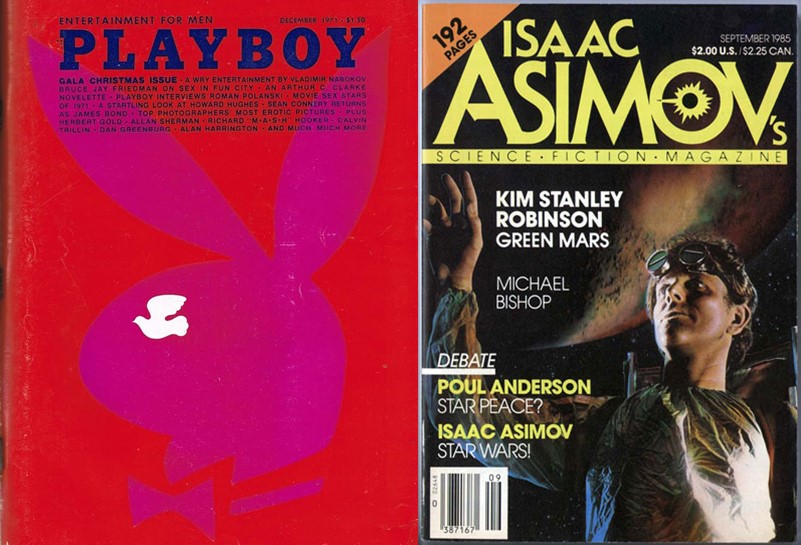

Meeting with Medusa was originally published in Playboy in December, 1971. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and Nebula Award, winning the latter, as well as the Seiun Award.

The novella opens with Captain Howard Falcon commanding a massive airship, the Queen Elizabeth IV, over the Grand Canyon. A collision with a drone camera causes the ship to crash, killing nearly everyone on-board, including the uplifted chimpanzees who served as part of their crew. Although horribly injured in the crash, Falcon survived and spends years regaining his ability to function, eventually returning to his job as a pilot with an audacious plan.

Falcon proposed a mission to fly through Jupiter’s atmosphere. He notes that many probes have been lost in the atmosphere, but believes that he is uniquely qualified for a crewed mission because he can take evasive action if necessary, noting that he was not at the helm when the Queen Elizabeth IV was struck. His proposal seems like a mix of hubris and a need to atone for the loss of the airship. While Falcon’s reasoning may make sense, the decision to fund and permit him to take on the mission seems a little too pat. However, characterization and motivation has never been Clarke’s forte.

Where Clarke excels, and where Meeting with Medusa succeeds, is building a sense of wonder for the reader. Extrapolating from what was known about Jupiter in the years prior to the first flyby, by Pioneer 10 in 1973, Clarke creates an alien world high in the Jovian atmosphere. Buffeted by hurricane force winds, Falcon provides testimony of the miracles of life that are able to exist there, from the enormous and buoyant medusa, named for the tentacles that dangled beneath them, to the ray-like predators that glide through the skies. The size of these creatures, and the requirements for living where they do, mean that Clarke has incorporated aspects of biology that only exist on a small scale on Earth, if at all.

Gardner Dozois commented that Meeting with Medusa “is a bit traveloguish,” but there is more to the story than simply Falcon’s sightseeing through Jupiter’s skies and achieving a sense of closure for the Queen Elizabeth incident. Clarke provides a more specific reason why Falcon may be the right person for the job, but that final revelation feels a little tacked on and Clarke didn’t make full use of it throughout the story.

Forty-five years after its original publication, authors Stephen Baxter, who collaborated with Clarke, and Alastair Reynolds published a sequel to Meeting with Medusa, the novel The Medusa Chronicles, which expanded on the world Clarke described and the character who explored that world.

Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, September 1985, cover by J.K. Potter

The novella Green Mars was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in September, 1985 and should not be confused with Robinson’s 1993 novel Green Mars. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award.

Roger Clayborne, who is around 300 years old, has resigned from his position as Minister of the Interior for Mars, a position he has held for 27 years. A member of the Red Party, which championed the maintenance of Mars in its natural state, he has come to realize that his ideology has lost out to the Greens, who have successfully terraformed Mars to an extent that conserving its pristine nature is no longer possible.

In his own attempt to get back to nature, Clayborne signs on with an expedition to climb Olympus Mons, at 22 kilometers, the tallest mountain in the solar system, with a peak that juts out of the planet’s atmosphere. All expert climbers, including a woman Clayborne knew more than 250 years earlier, the trek up the mountain proves dangerous, between the threat of rockfall, weather, and the thinner Martian atmosphere.

Set over the span of several weeks, Clayborne interacts with nearly all of the other members of the expedition in various ways and the expedition leader, Eileen Monday, makes sure to rotate who partners with whom. With a cast of eleven characters, some do get short shrift (only one of the four “Sherpas” is given a last name and none of them are fleshed out), but Robinson does limn out distinctions between most of the characters, from Marie Whillans’ exuberance to Dougal Burke’s quiet competence. Roger’s interactions often depict part of the story, but Robinson makes clear that there are complex relationships behind the scenes.

Robinson also describes the climb in details, introducing the reader to a variety of concepts used to scale mountains and showing that, even with the relatively gentle slope of Olympus Mons, the ascent is difficult, with a lot of climbing and descending as paths and dead ends are discovered and materials are carefully positioned to ensure the expedition’s chance of success. At the same time, injuries happen and must be dealt with, not always in the most obvious ways.

As Clayborne climbs the mountain, the natural beauty and his discussions with the other climbers slowly begins to make him reconsider what it means to be a Red in a world in which terraforming has already taken hold. By the time he reaches the summit, he comes to a conclusion that he can still work to preserve Mars under what he considers to be less than ideal circumstances, but also understands that a terraformed Mars as a beauty all its own.

Both stories are explorations of strange vistas, with Clarke exploring the atmosphere of Jupiter and raising perceptual questions about both the concept of landscapes and life, introducing cloudbanks that were seen as mountains and massive creatures that lived in the atmosphere, never landing. Robinson presented the different layers of Olympus Mons, drawing parallels between mountains and rock formations on Earth with those on Mars as his climbers made the dangerous ascent. However, while both are explorations into the unknown, Robinson also focused on the relationships between the members of his climbing expedition, while Clarke’s protagonist spends most of the story is solitude. The result of this is that the strength of Robinson’s characters highlights the weakness of Clarke’s characters.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

I remember reading Meeting with Medusa in one of those Nebula Award Winner anthologies, while I thought the award should of gone to The Fifth Head of Cerberus, I was suitably impressed. It does have a sense of wonder and I actually think the “travelogueishness” helps in that way.

I first read the Clarke story in a Science Fiction Book Club hardcover edition of “The Wind From The Sun” as a junior high student. I remember it like it was yesterday and at that age the very “traveloguish” nature of the story was it’s main appeal as I was at the peak of my interest in hard science fiction (within the year I discovered Harlan Ellison and headed off on an entirely different tangent).

I actually think that Falcon’s solitude enhances his characterization rather than diminishes it and while that may be my own personality prejudice I find that few science fiction authors have a deft enough hand at characterization to juggle a cast of fully fleshed out characters with a compelling plot. I do think Clarke could have dispensed with the opening prologue which felt clumsy even to my 12-year-old self while the altered chimps were a detail both cheesey and depressing that the story could have done without. As for giant airships, as romantic as the notion is I really don’t think we’ll ever see such beauties gracing the skies again.

I’ve never gotten around to reading any Robinson. I always meant to and you’ve rekindled my interest. I do miss old school harder science fiction with a touch of the grandiose like this although I have to wonder if the story might have been more effective by mirroring Clarke’s approach and focusing on just one or two climbers at most and telling it as an internal monolog.